Remembering the Great Fire of London

29th September 2016

Remembering the Great Fire of London

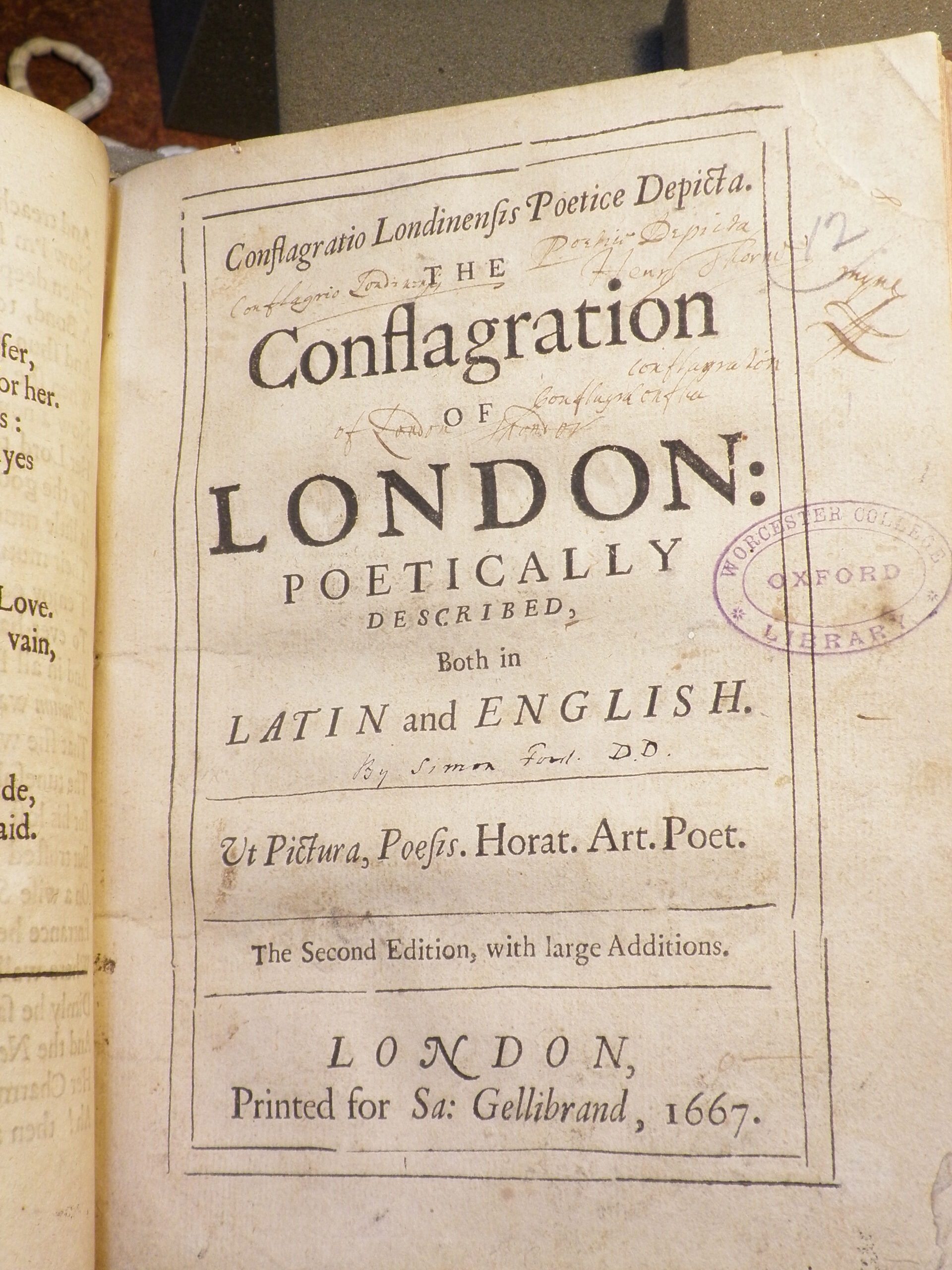

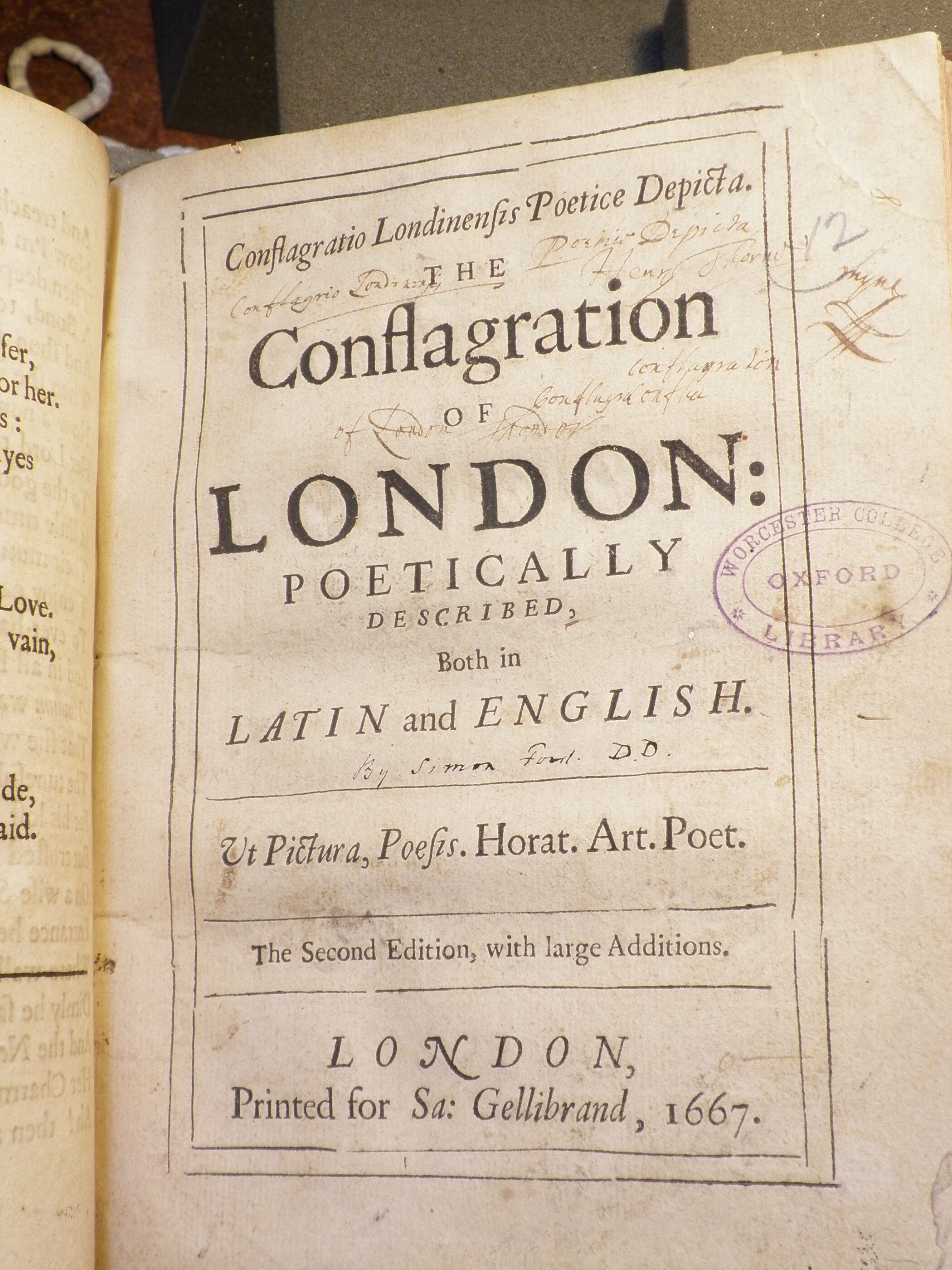

Conflagratio Londinensis poetice depicta. The conflagration of London: poetically described, both in Latin and English. The second edition, with large additions.

London : Printed for Sa: Gellibrand, 1667.

22 [i.e. 32] pages ; quarto.

A Fatal Fire conceiv’d in private Walls,

Nurs’d by Contempt, at last grows past Arrest;

Defies all Aides, and scorns to be supprest.

(lines 31-33)

Two of this year’s blog posts have already carried intimations of the subject of September’s entry: in April (Shakespeare and a Trio of Folios), we noted the rarity of Shakespeare’s Third Folio, many copies of which were destroyed in the Great Fire of London; in June (‘One of the two greatest books’ of seventeenth-century science: Harvey’s De motu cordis), mention was made of the Library of the College of Physicians, also destroyed in the fire. In the 350th anniversary year of one of the seventeenth century’s great calamities, it seemed fitting to search in the Worcester College Library collection (itself strong in seventeenth-century history) for items relating to the Great Fire of 1666. In addition to contemporary pamphlets publishing proclamations concerning the fire and investigations by committees appointed to investigate its causes, we found The Conflagration of London, a poem in English and Latin by Simon Ford (1618/19-1699) (a modern printing can be found in Aubin, London in flames, London in glory). This commemorates the fire that broke out in the early hours of Sunday 2nd September 1666 and burned until Thursday 6th September. Although fewer than ten people are known to have died in the fire, the impact was far greater: many more died afterwards, succumbing to disease as they faced a harsh winter in makeshift accommodation, with over 13,000 houses and 400 acres of land having been destroyed (Hornak, After the fire, page 15):

And Houses mix’d, to mixed Ashes turn.

What was the Nurse of Trade, becomes its Fate;

And Neighbourhood doth now depopulate…

(lines 70-72)

A Church of England clergyman, Ford involved himself in several religious controversies (see ODNB), yet Anthony Wood also pronounced him ‘a most celebrated Latin Poet of his time… he ought to be numbered hereafter among the Oxford writers’ (Fasti, II, column 283). Andrew Marvell, writing to Lord Wharton in April 1667 and perhaps referring to this edition of The Conflagration of London, speaks of ‘a Poem, writ… by Mr Ford… : the Latin, in this last, (if I may presume to censure in your Lordships presence) hath severall excellent heights, but the English translation is not so good; and both of them strain for wit and conceit more then becomes the gravity of the author or the sadnesse of the subject’ (Andrew Marvell, The poems and letters, ed. Margoliouth, page 310). E. E. Duncan-Jones, editing the revised edition of Marvell’s letter, concurs that the poem ‘fully justifies Marvell’s censure’! It is, indeed, somewhat hyperbolic in places:

That reverend Fabrick which the World admir’d,

Amongst a crowd of lesser note is fir’d.

Its Cloud-surmounting Steeple flam’d so high,

That threaten’d Heavens ne’re feare’d a flame so nigh.

(lines 225-228)

Yet, whatever the poetic merits of Ford’s poem, the volume also holds interest from a book-historical viewpoint, given that it was printed for Samuel Gellibrand (d. 1675). Gellibrand’s bookshop had been located in St Paul’s Churchyard: first (from 1639) at the Brazen Serpent, then (1650-1675) at The (Golden) Ball (see Blayney, The bookshops in Paul’s Cross Churchyard, page 85); but in 1667 no Paul’s Churchyard remained to feature on title pages.

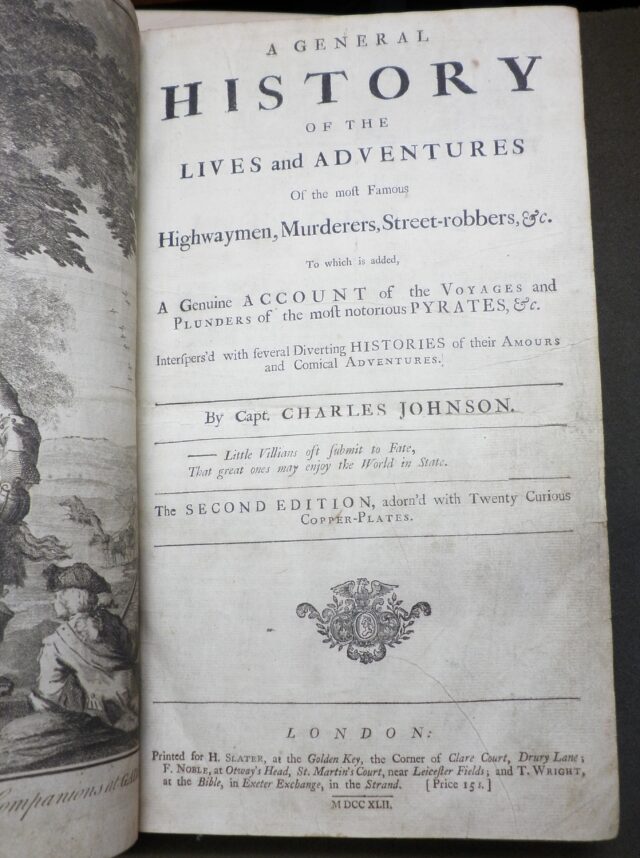

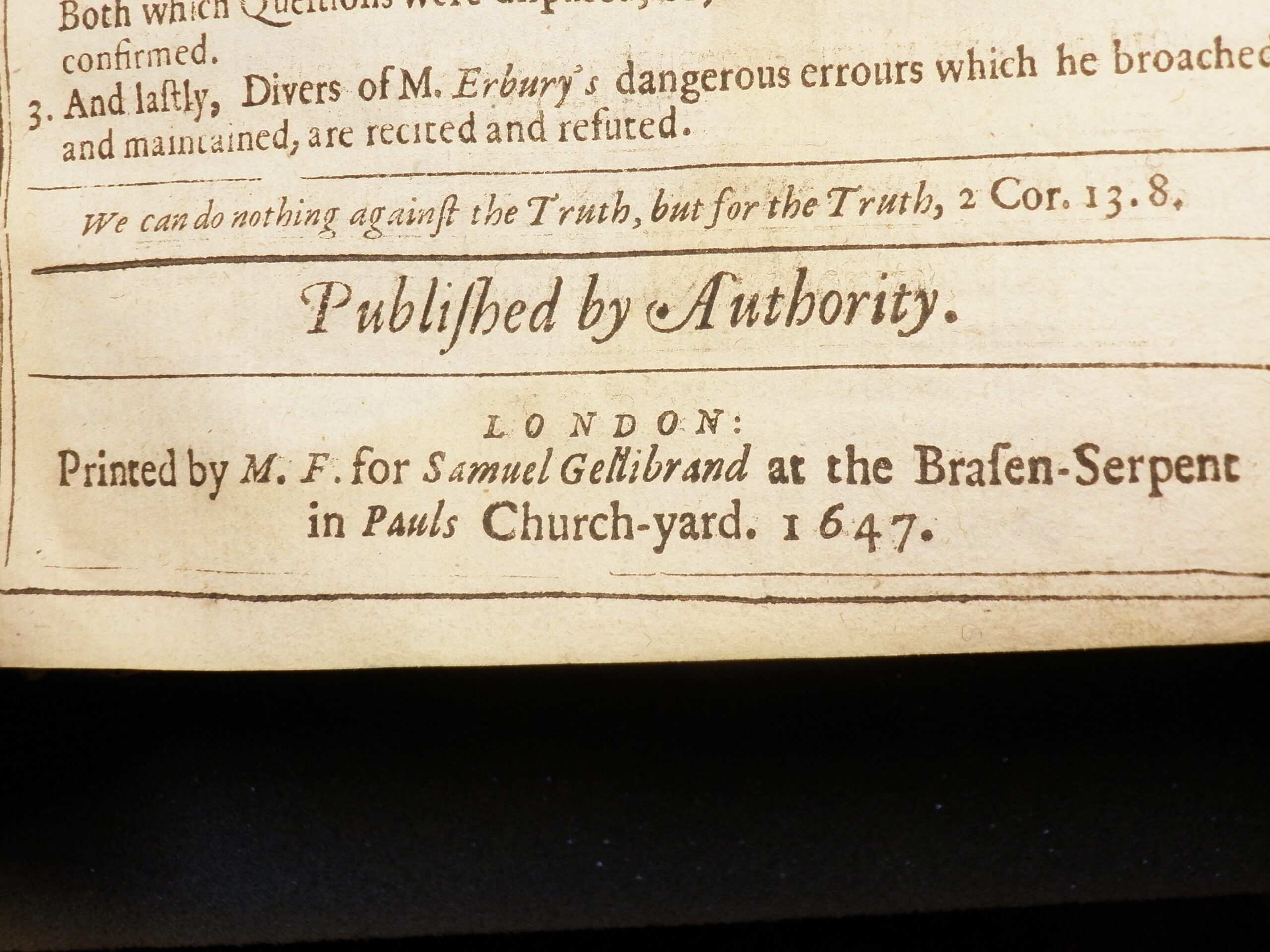

Gellibrand’s imprint (‘at the Brasen-Serpent’) from a 1647 publication (Francis Cheynell, An account given to the Parliament by the ministers sent by them to Oxford)

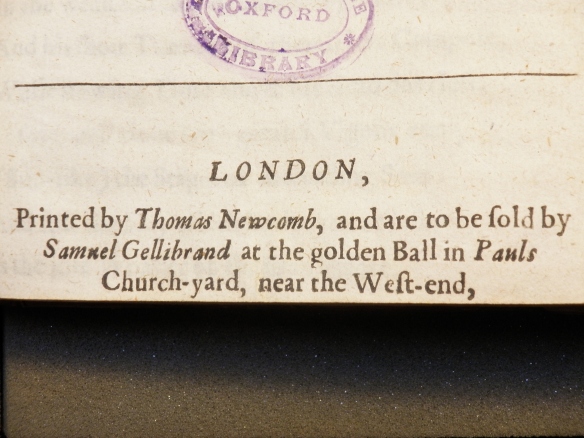

Gellibrand’s imprint (this time ‘at the golden Ball’) from a 1655 publication (Andrew Marvell, The first anniversary of the government under His Highness the Lord Protector)

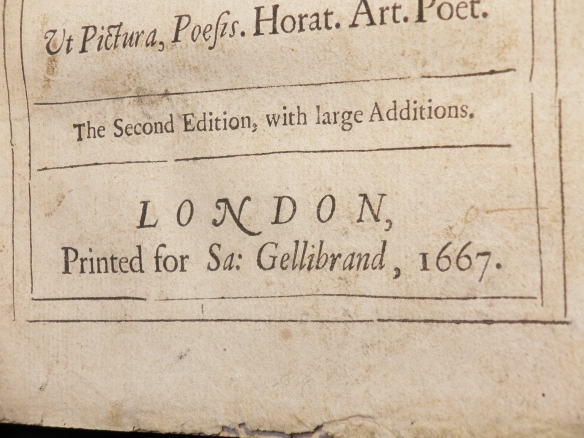

Gellibrand’s imprint from 1667 on the title page of The conflagration of London

The Great Fire destroyed both Old St Paul’s Cathedral and all the bookshops that had occupied its churchyard and environs. Indeed, one impact of the fire was to decimate ‘both the stocks of London booksellers and the productive capacity of the London presses’ (Raymond, Pamphlets and pamphleteering in early modern Britain, page 165). Much stock was destroyed in the crypt of St Paul’s (in which the local parish church, St Faith’s, was located) where stationers had put their books for safety:

The Labours of the teeming Press and Brain,

(An off-spring Ages can’t restore again)

One Hour destroyes. St Faith’s betrusted Cell,

(For publique Faith it was) turn’d Infidel.

(lines 251-254)

St Paul’s Churchyard, which had been one of ‘the most prominent sites in all of England for publishers and printers to set up shop’ (Hentschell, ‘The cultural geography of St Paul’s precinct’, page 639) was reduced to a rubble-yard. Happily the churchyard was rebuilt together with the cathedral, and booksellers did return there by the 1680s (Raven, Bookscape, page 59).

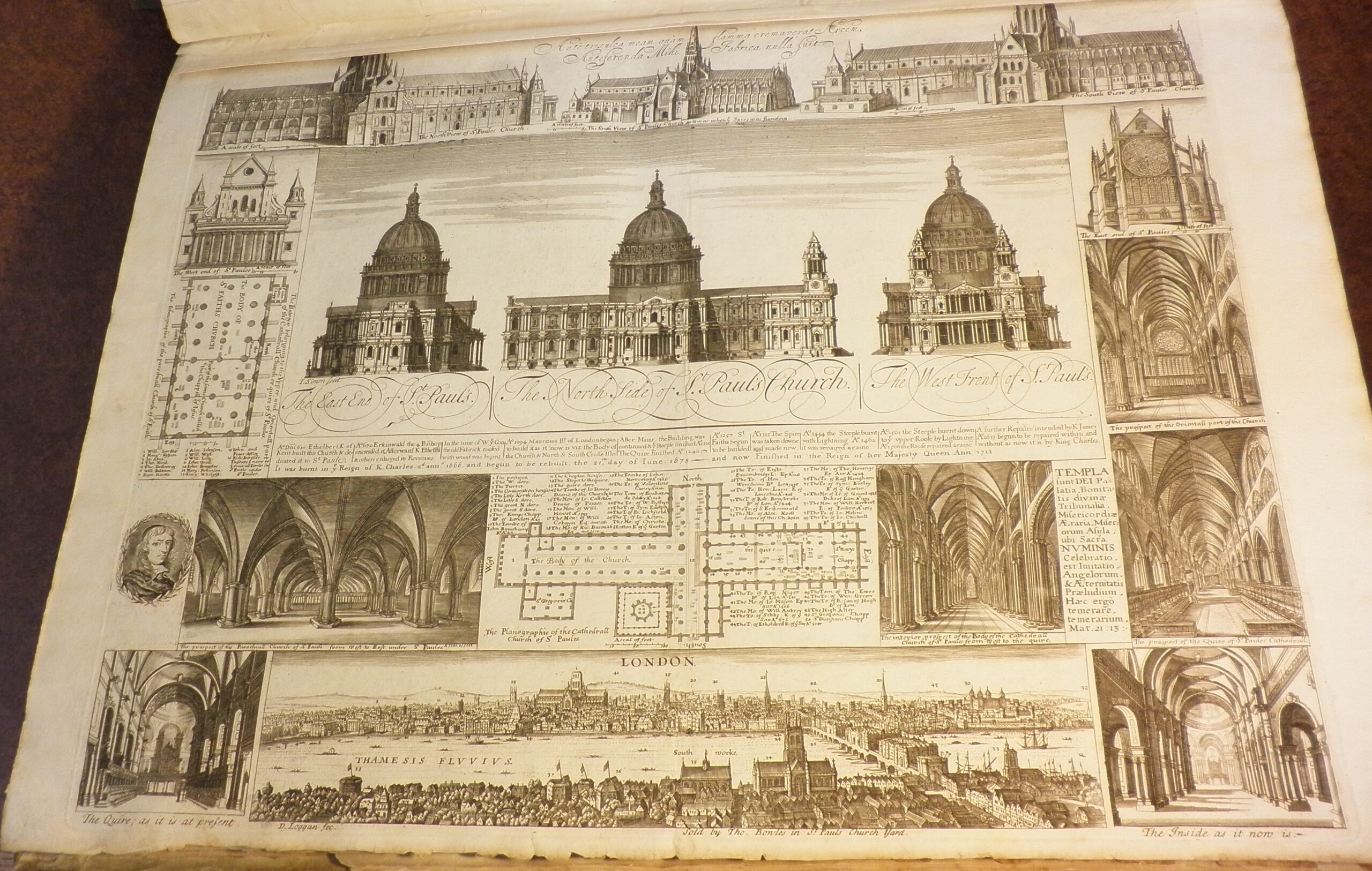

Views of Old and New St Pauls. Engraved by David Loggan and Simon James (published 1713)

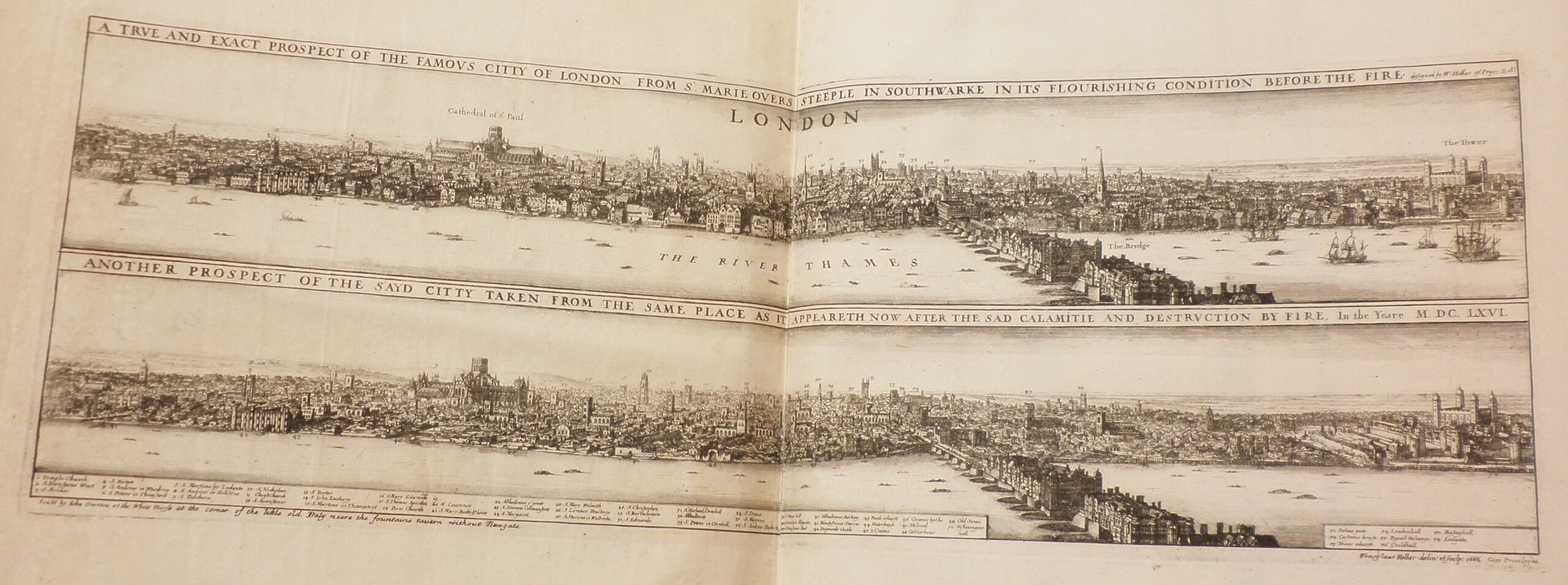

The above print by David Loggan and Simon James (http://prints.worc.ox.ac.uk/scripts/fullrecordid.asp?ident=18) illustrates both Old and New St Paul’s. Although Ford’s poem can give an impression of how the fire was experienced by Londoners, it is perhaps in pictures that the impact of the Fire on the City of London – five sixths of which was destroyed – can best be understood. This is true of Wenceslaus Hollar’s print, London before and after the Great Fire (see http://prints.worc.ox.ac.uk/scripts/fullrecordid.asp?ident=14): it shows the devastation of the burned-out City, with the Tower of London standing intact to the right, and the ruin of Old St Paul’s to the left. All this is set in contrast to a version of Hollar’s earlier Long View of 1647, printed directly above (see Godfrey, Wenceslaus Hollar, page 140; Griffiths and Kesnerová, Wenceslaus Hollar, page 86).

London before and after the Great Fire. Engraved by Wenceslaus Hollar (published 1700).

The Fate of old Troy did New-Troy betide,

Its doubtful Pedigree’s thus justifi’d.

The City-now is the once-City’s Tomb,

A Sceleton of fleshless Bones become.

(lines 319-322)

Mark Bainbridge, Librarian

Bibliography

- Aubin, R. A., London in flames, London in glory: poems on the fire and rebuilding of London, 1666-1709 (New Brunswick, 1943)

- Blayney, P., The Bookshops in Paul’s Cross Churchyard (London, 1990)

- Godfrey, R. T., Wenceslaus Hollar: a Bohemian artist in England (New Haven, 1994)

- Griffiths, A. and G. Kesnerová, Wenceslaus Hollar: prints and drawings from the collections of the National Gallery, Prague, and the British Museum, London (London, 1983)

- Hentschell, R., ‘The cultural geography of St Paul’s precinct’, in Smuts, R. M. (ed.), The Oxford handbook of the age of Shakespeare (Oxford, 2016), pages 633-649

- Hornak, A., After the fire: London churches in the age of Wren, Hooke, Hawksmoor and Gibbs (London, 2016)

- Margoliouth, H. M. (ed.), The poems and letters of Andrew Marvell, 3rd ed. revised by Pierre Legouis with the collaboration of E. E. Duncan-Jones (Oxford, 1971)

- Raymond, J., Pamphlets and pamphleteering in early modern Britain (Cambridge, 2003)

- Raven, J., Bookscape: geographies of printing and publishing in London before 1800 (London, 2014)

- Wood, A., Fasti Oxonienses in P. Bliss (ed.), Athenae Oxonienses (reprint ed., Hildesheim, 1969)