Fashionable Fairies

27th February 2020

Fashionable Fairies

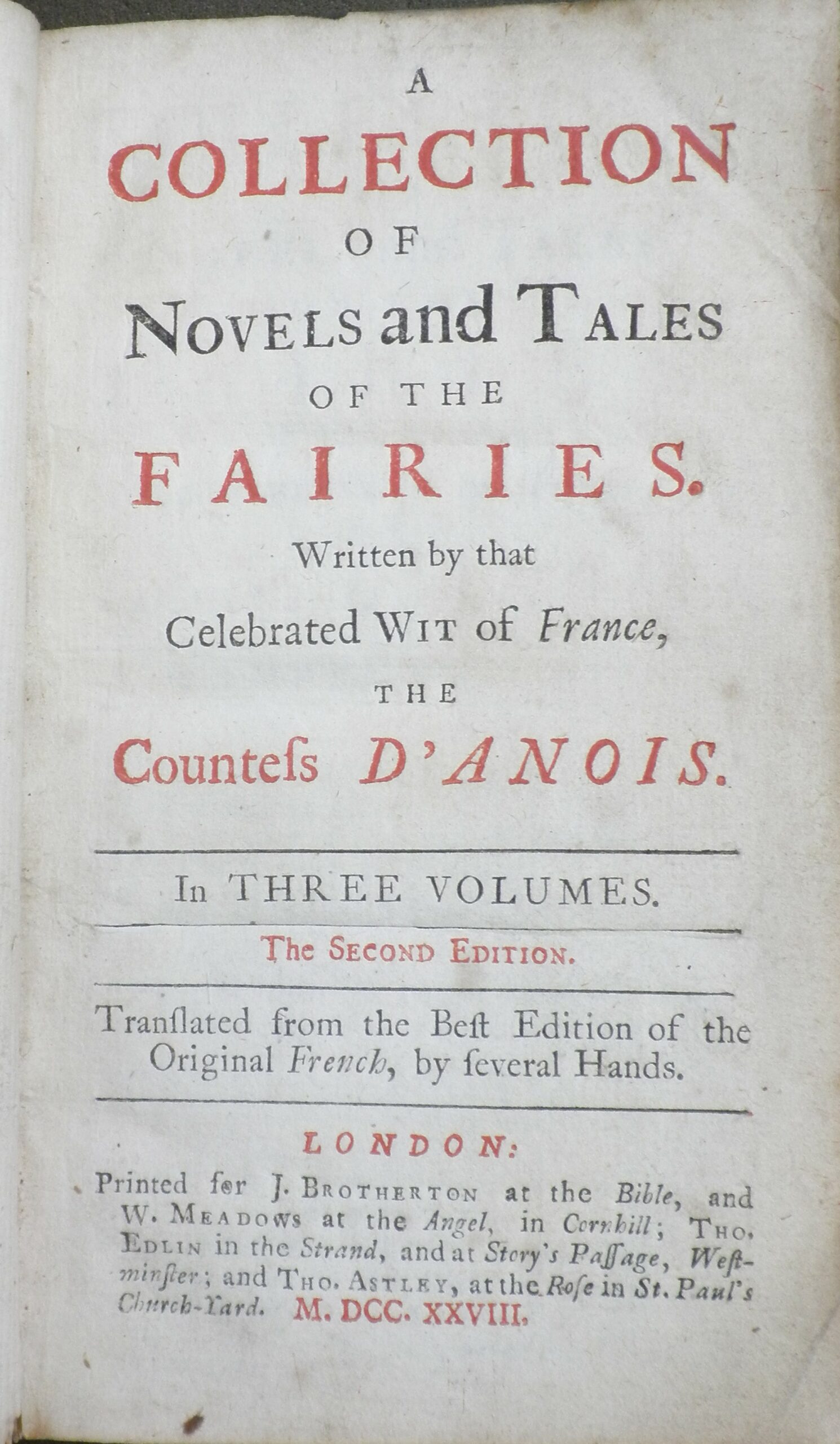

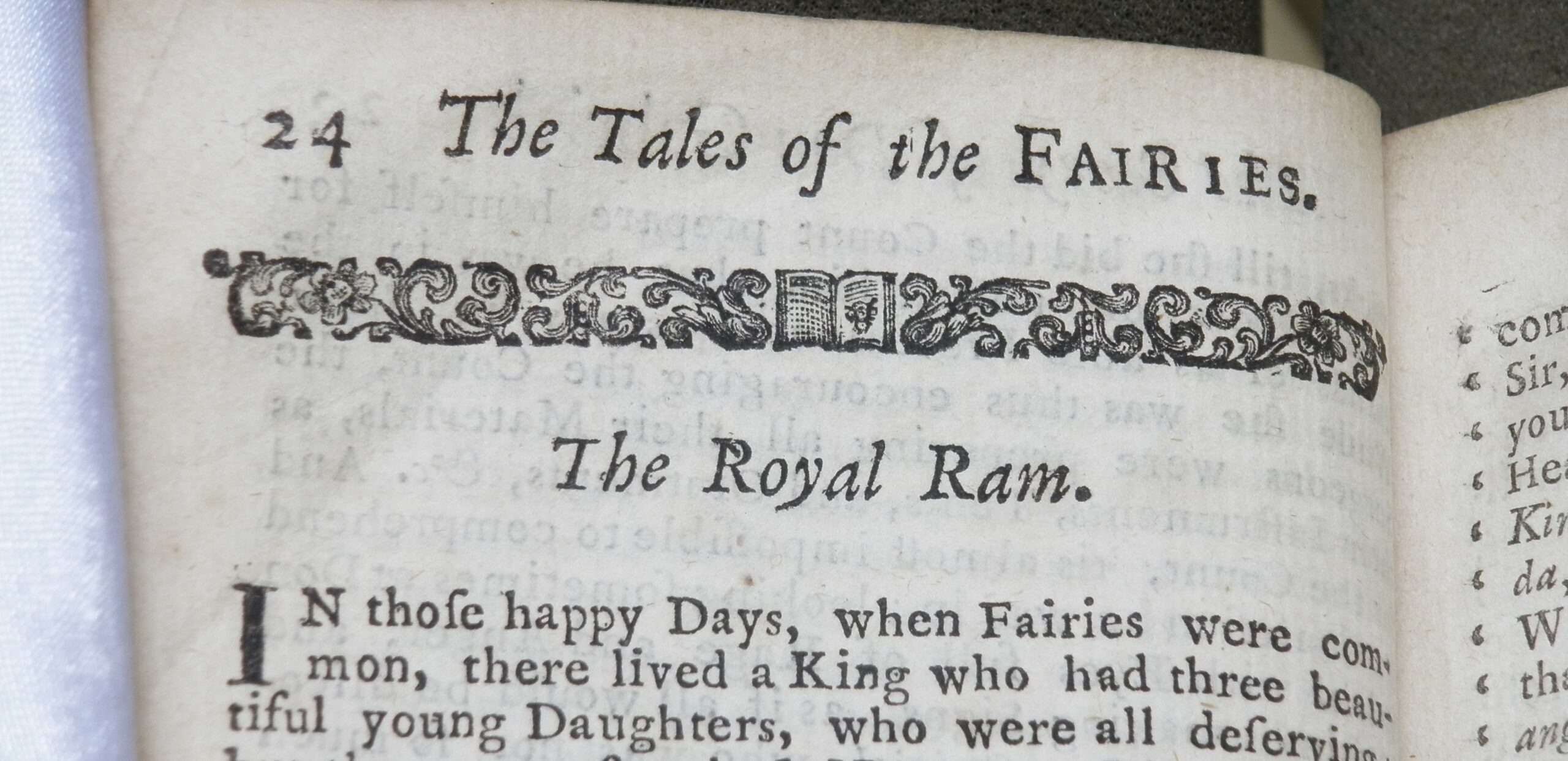

A Collection of Novels and Tales of the Fairies. Written by that Celebrated Wit of France, the Countess D’Anois.

The Second Edition, London: Printed for J. Brotherton at the Bible, and W. Meadows at the Angel, in Cornhill; Tho. Edlin in the Strand, and at Story’s Passage, Westminster; and Tho. Astley, at the Rose in St. Paul’s Church-Yard. M. DCC. XXVIII. (1728)

Our treasure this month is a small, well-loved three volume set of fairy tales by Marie-Catherine d’Aulnoy. Though something of a literary celebrity in her day, both in France and in England, Madame d’Aulnoy and her work were virtually forgotten by the twentieth century. Only in the last thirty years or so has there been a revival of interest in her work, led largely by the growing academic study of fairy tales.

The life of Marie-Catherine, Baronne or Comtesse d’Aulnoy (1650/1-1705) is as fascinating and mysterious as one of her tales (for more details, please see her entry by Lewis Seifert in the Oxford Companion to Fairy Tales). She was married young, aged 15 or 16, to the Baron d’Aulnoy, who was thirty years her senior. In 1669, after several years of mistreatment, she plotted with her mother and two men to have him arrested for treason, a capital offence. When the Baron was acquitted, he brought charges against his accusers which led to the execution of the male accomplices, exile for Madame d’Aulnoy’s mother, and brief imprisonment for Mme d’Aulnoy (Seifert, Companion to Fairy Tales). Exactly what became of Mme d’Aulnoy in the years 1670-1690 is unknown. It’s generally agreed that she probably travelled to Flanders, England, and Spain, and Warner goes so far to suggest that she may have been a spy for France during this time (Warner, From the Beast to the Blonde, p. 285). Upon her return to Paris in 1685, she established herself as part of literary polite society and began a prolific writing career (Seifert, Companion; Warner, Beast to Blonde, p. 285).

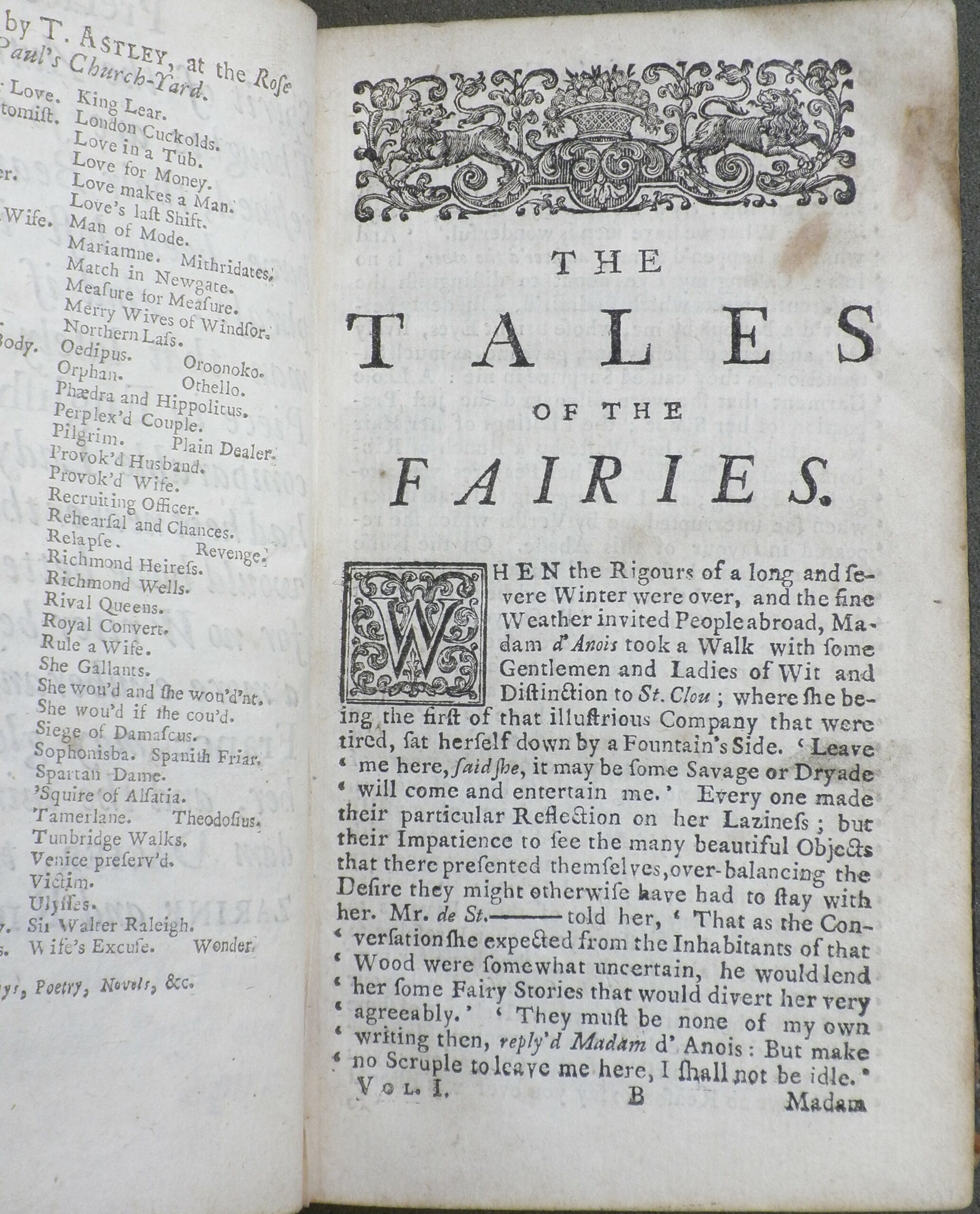

Mme d’Aulnoy wrote travelogues, novels, short stories, devotional works, and historical memoirs, but her lasting legacy has been her fairy tales (Seifert, Companion). Fairy tales were all the rage in late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century France and Mme d’Aulnoy was a significant force in the development of the genre. She is credited with coining the term conte de fée (fairy tale), as well as publishing the first one – ‘L’île de la félicité’ (‘The Isle of Happiness’) in the longer work L’histoire d’Hypolite in 1690 (Seifert, Companion; Thirard, The Oxford Encyclopaedia of Children’s Literature). She then published two more collections of just fairy tales; Les Contes des fées (The Fairy Tales) in 1697 and Contes nouveaux où les fées à mode (New Stories, or, Fashionable Fairies) in 1698 (Thirard, Encyclopaedia).

The fairy tales published by d’Aulnoy and her contemporaries, such as Charles Perrault and Marie-Jeanne L’Héritier de Villandon, were not written for children – they originated in the Parisian salon and were intended for educated, upper class adults (Seifert, Fairy Tales, Sexuality, and Gender in France, p.1, p. 8). They were usually set in ‘frame stories’ – narratives which provided a context for storytelling – some as simple as a salon where ladies are amusing each other with tales and others, such as d’Aulnoy’s Don Gabriel in Les Contes des fées, which are essentially novellas. Although they are often purported to be based on memories of stories told by nursemaids and similar figures, the extent to which the literary fairy tales of this era were derived from folkloric sources, earlier literary sources, or pure imagination is contested among literary scholars (see Ruth B. Bottigheimer, Fairy Tales: a new history). Though few of Mme d’Aulnoy’s tales are well-known today, the motifs are familiar. In ‘The story of Finetta the cinder-girl’, for example, we have a disinherited royal heroine who escapes abandonment in the woods by leaving a trail of ashes as she travels, defeats a giant by tricking him into climbing into his own oven, and then after being forced into the role of servant by her evil sisters, manages to sneak off to royal balls, where she wins the heart of the prince, who tracks her down through the classic lost shoe method.

Mme d’Aulnoy was also wildly popular in England in the eighteenth-century, initially for her writings on the Spanish court, and later for her fairy tales. By 1721 ten of her works had been published in England and by 1740 there had been 36 editions of her work in English (Palmer, ‘Madame d’Aulnoy in England’, p.237). Such was her name recognition that works were often falsely attributed to her, presumably to increase sales (Palmer, ‘Madame d’Aulnoy’, p. 239). Our English edition of her tales was published in 1728 and while the frame stories and eight of the tales in the first two volumes are by Mme d’Aulnoy, four of the stories are by Henriette-Julie de Castelnau, Comtesse de Murat, a contemporary of d’Aulnoy. None of the stories in the third volume are hers – the majority were written by another contemporary, Louise Comtesse d’Auneuil (Palmer and Palmer, ‘English Editions of French “Contes de Fées” Attributed to Mme D’Aulnoy’, pp. 230-231).

It was over the course of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that fairy tales were repackaged as stories for children. Both in France and England popular fairy tales were reprinted in cheaper editions and often abridged and adapted for different audiences (Bottigheimer, Fairy Tales, p. 103). Warner notes that Mme d’Aulnoy and other tale-tellers were frequent victims of bowdlerization in England; the sexuality and light-hearted brutality of some of Mme d’Aulnoy’s tales in particular were considered distasteful to English audiences (Warner, Beast to Blonde, p. 166, p. 284). As her tales were reprinted and rewritten in England, mythical figures also replaced her as author – first she became Queen Mab, then by the 1770s she had become ‘Mother Bunch’ (Jones, ‘Madame d’Aulnoy Charms the British’, p. 255). It was under the name of Mother Bunch that her stories were first marketed specifically to children, in a volume titled Mother Bunch’s Fairy Tales. Published for the amusement of all those Little Masters and Misses who, by duty to their parents, and obedience to their superiors, aim at becoming Great Lords and Ladies, published by Francis Newbery in 1776 (Jones, ‘Madame d’Aulnoy Charms the British’, p. 253).

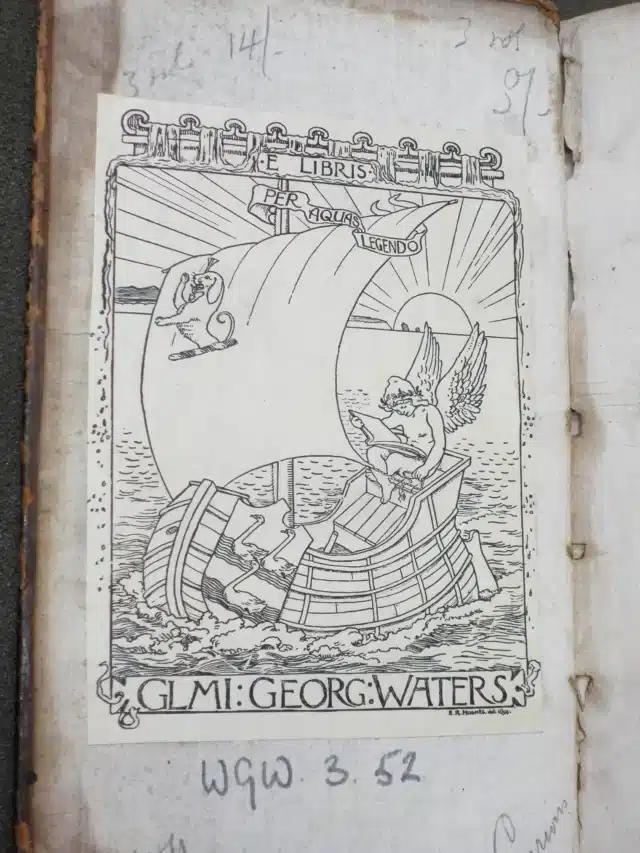

Our copy of Mme d’Aulnoy’s tales come from the collection of W.G. Waters, who was a Fellow Commoner of Worcester College (an undergraduate who paid an extra fee to eat in the Senior Common Room – he may have chosen to do this because at 27 he was much older than most undergraduates)¹ from 1869-1872. After his death in 1928, Waters’ son offered the College the bulk of his father’s book collection in 1936/37. A bust of W.G. Waters continues to watch over the collection in the entrance hall to the Lower Library.

- Bust of W.G. Waters

- Bookplate of W.G. Waters

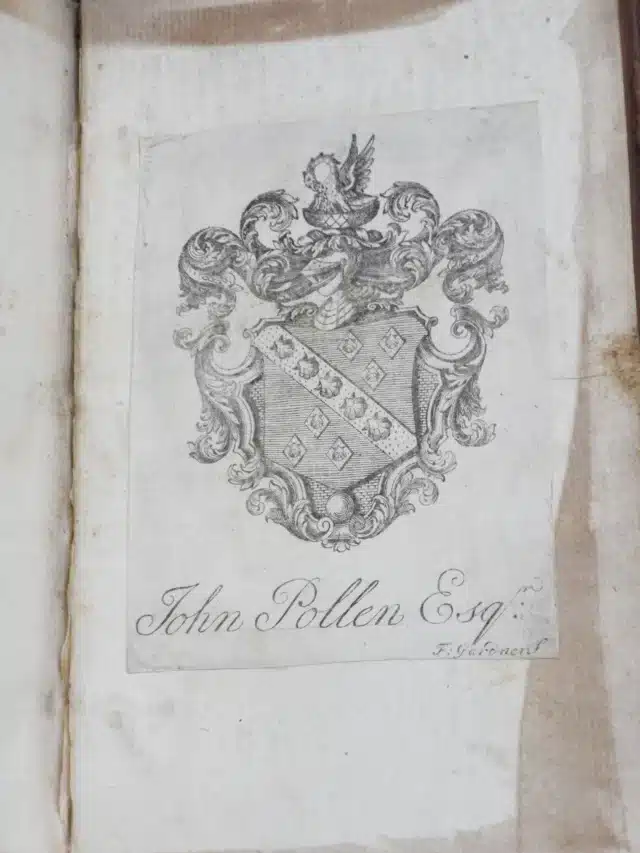

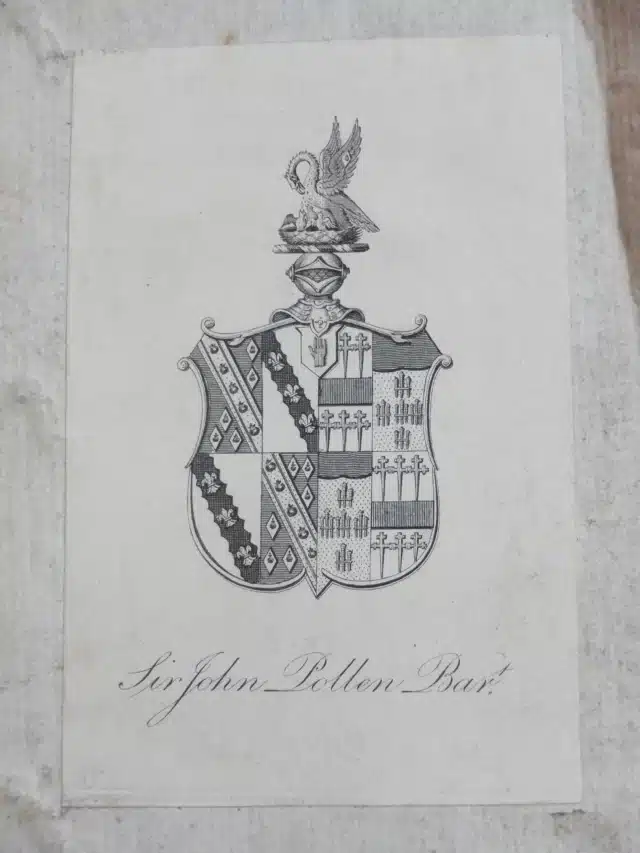

Before Waters, the books were owned by Sir John Pollen (1784-1863), second baronet, and his grandfather, also called John Pollen (c. 1702-1775).² One book has a bookplate for ‘John Pollen, Esquire’ and another for ‘Sir John Pollen, Baronet’.

- Bookplate of John Pollen

- Bookplate of Sir John Pollen

The condition of the books – worn leather, dented edges, and detached boards – suggests that they have been well-read and well-loved; a testament to the continuing appeal of fairy tales over the course of 300 years.

Renée Prud’Homme, Assistant Librarian

¹ Thanks to our archivist Emma Goodrum for information about Fellow Commoners.

² Edit 31/3/25: originally, we incorrectly ascribed Sir John Pollen’s bookplate to the first baronet, also called Sir John Pollen (1731-1814), and the post has been edited to correct this. With thanks to Anthony Pincott for the corrections and information related to the bookplates.

Bibliography

- Bottigheimer, Ruth B., Fairy Tales: a New History (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2009)

- Burke, Sir Bernard, A Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Peerage and Baronetage of the British Empire (London, 1865)

- Jones, Christine A., ‘Madame d’Aulnoy Charms the British’, Romantic Review 99:3/4 (May-Nov 2008), pp. 236-256, accessed online: https://search.proquest.com/docview/196423926?accountid=13042

- Palmer, Melvin, ‘Madame d’Aulnoy in England’, Comparative Literature 27:3 (Summer 1975), pp. 237-253, accessed online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1769548

- Palmer, Nancy and Melvin Palmer, ‘English Editions of French “Contes de Fées” Attributed to Mme D’Aulnoy’, Studies in Bibliography 27 (1974), pp. 227-232, accessed online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40371596

- Seifert, Lewis C., ‘Aulnoy, Marie-Catherine Le Jumel de Barneville Baronne d’ [or Comtesse] (1650/51-1705)’ in The Oxford Companion to Fairy Tales, ed. Jack Zipes (OUP 2005, accessed online: https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199689828.001.0001/acref-9780199689828-e-43)

- Seifert, Lewis C., Fairy Tales, Sexuality, and Gender in France 1690-1715: Nostalgic Utopias (Cambridge: CUP, 1996)

- Thirard, Marie-Agnès, ‘Aulnoy, Marie Catherine, Comtesse d’’, The Oxford Encyclopaedia of Children’s Literature, ed. Jack Zipes (OUP 2006, accessed online: https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195146561.001.0001/acref-9780195146561-e-0160)

- Warner, Marina, From the Beast to the Blonde: on Fairy Tales and their Tellers (London: Vintage, 1995)