‘One of the two greatest books’ of seventeenth-century science: Harvey’s De motu cordis

30th June 2016

‘One of the two greatest books’ of seventeenth-century science: Harvey’s De motu cordis

Recentiorum disceptationes de motu cordis, sanguinis, et chyli, in animalibus. Quorum series post alteram paginam exhibetur.

Lugduni Batavorum: ex officina Ioannis Maire, M D C XLVII.

Worcester College’s library collections are justly known for their strengths in architectural history and in seventeenth-century history and literature, but this risks losing sight of the many medical and scientific texts that also make up the special collections. The Library’s major benefactor, George Clarke (1661-1736) collected in all the areas of learning of his day, and so recently the Library was able to make a positive reply to a request from one of our medicine undergraduates: “Does the Library have any of the works of William Harvey?”

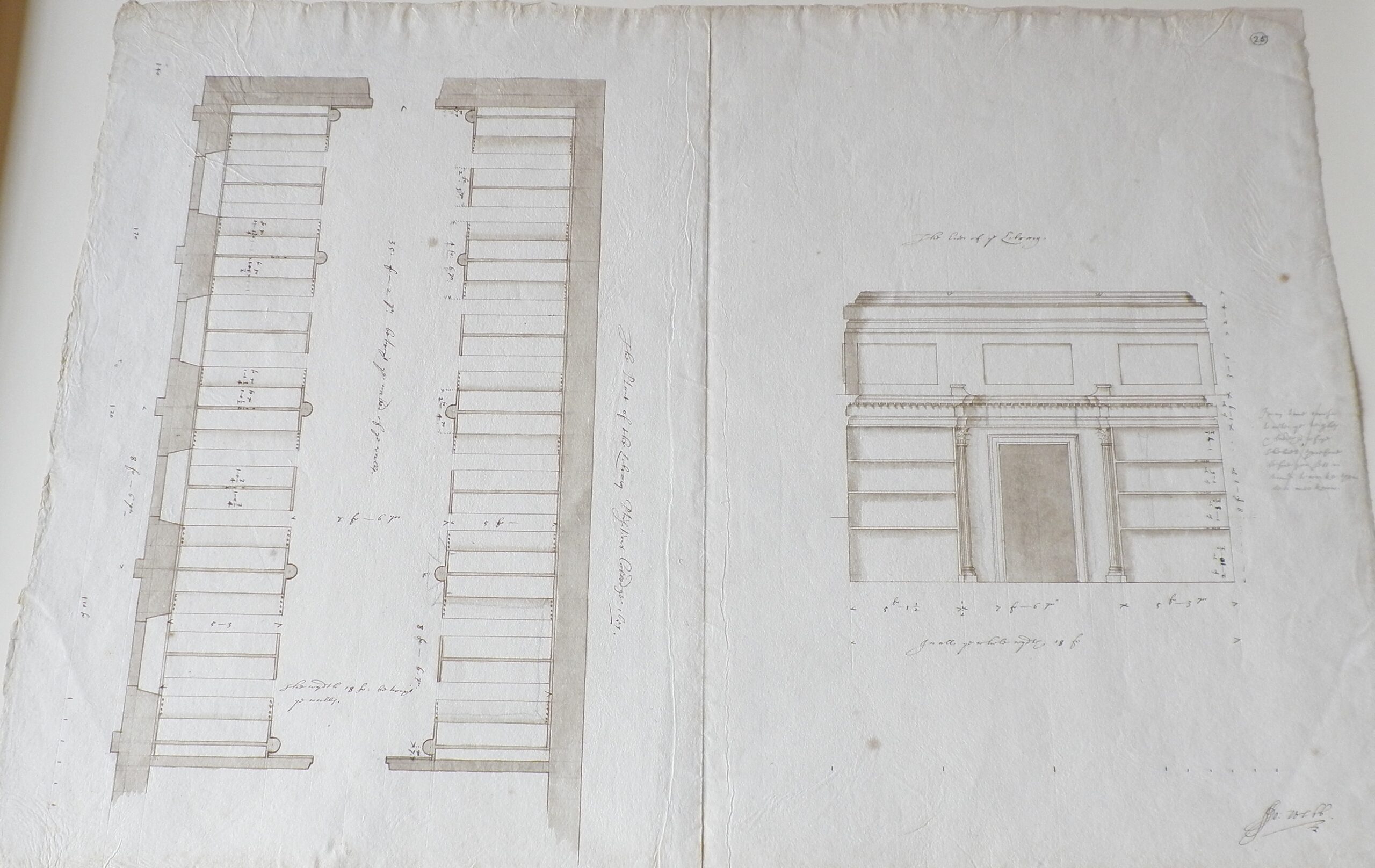

William Harvey (1578-1657) studied medicine at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, before entering the College of Physicians in 1604. By 1618 he had come to the attention of the Stuart Court, where he served as physician-extraordinary to James VI and I. His career culminated in his appointment as physician-in-ordinary (that is, as personal physician) to Charles I in December 1639. During the Civil War he accompanied the king to Oxford, where he was appointed Warden of Merton College by royal decree in 1645. After the surrender of Oxford, he returned to London, and, in what he possibly found the uncomfortable atmosphere of the new Commonwealth, concentrated his attentions and generosity on the College of Physicians (where his work as Lumleian lecturer since 1615 perhaps began his investigations into the circulation of the blood – see the Everyman edition of Harvey’s works, page xix). Such is the strength of Worcester College Library’s seventeenth-century collections that we should perhaps not be too surprised to find among our drawings John Webb’s designs for Harvey’s gift to the College of Physicians, a library completed in February 1654:

John Webb, Design for Library, Repository and Consulting Room, College of Physicians, Elevation of a pilastered front (Harris and Tait 75)

John Webb, Design for Library, Repository and Consulting Room, College of Physicians, Plan and elevation of end wall of Library (Harris and Tait 78)

This piece, however, is not on the subject of Webb’s drawings, beautiful though they are, but rather on a text that would undoubtedly have graced the shelves of the College of Physicians’ Library: Harvey’s De motu cordis et sanguinis in animalibus anatomica exercitatio (An anatomical exercise on the motion of the heart and blood in animals, commonly called De motu cordis), which has been described as ‘one of the two greatest books’ of seventeenth-century science (see Weil, ‘William Fitzer…’, page 142; the other seventeenth-century scientific title is Newton’s Principia).

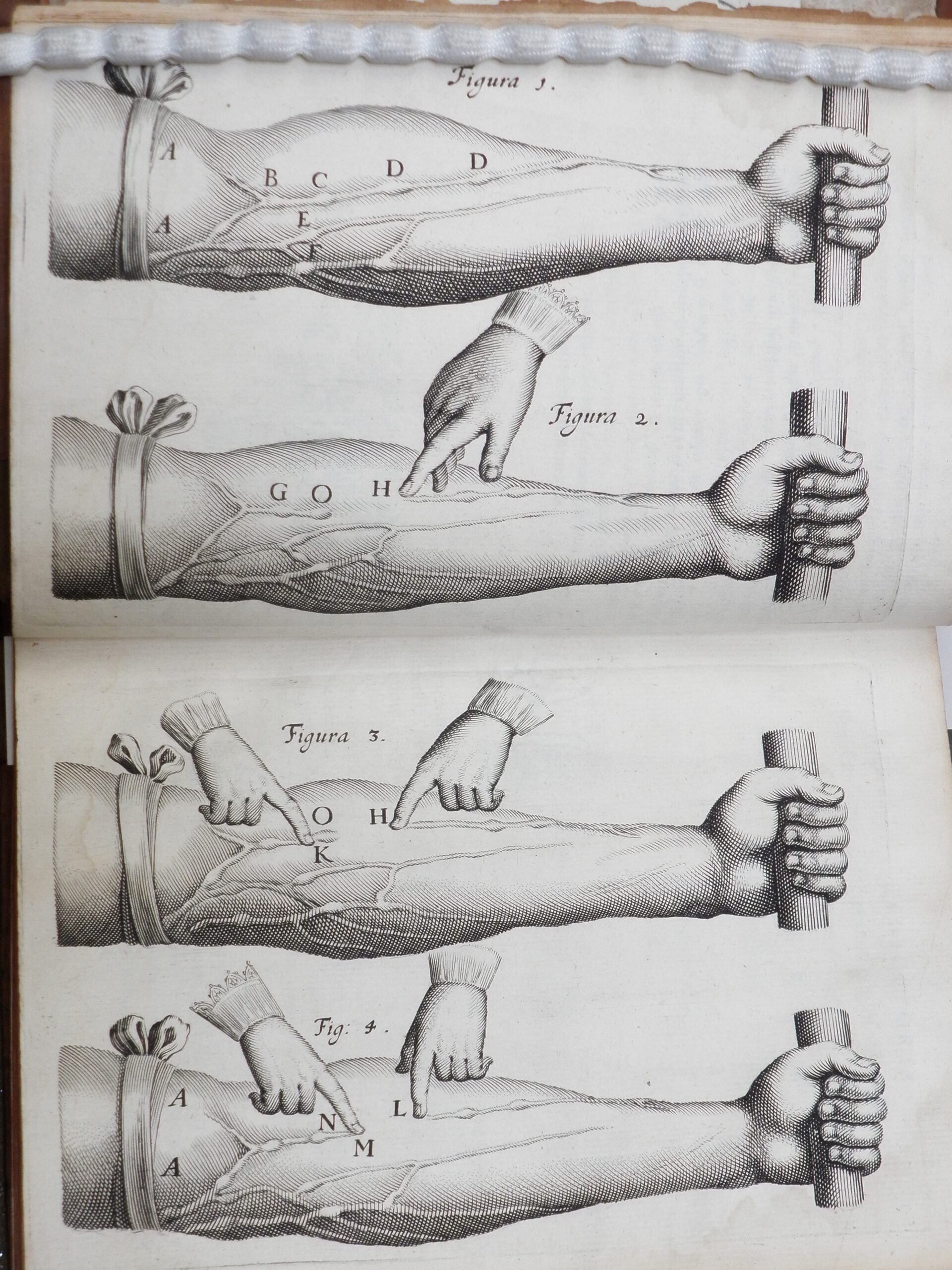

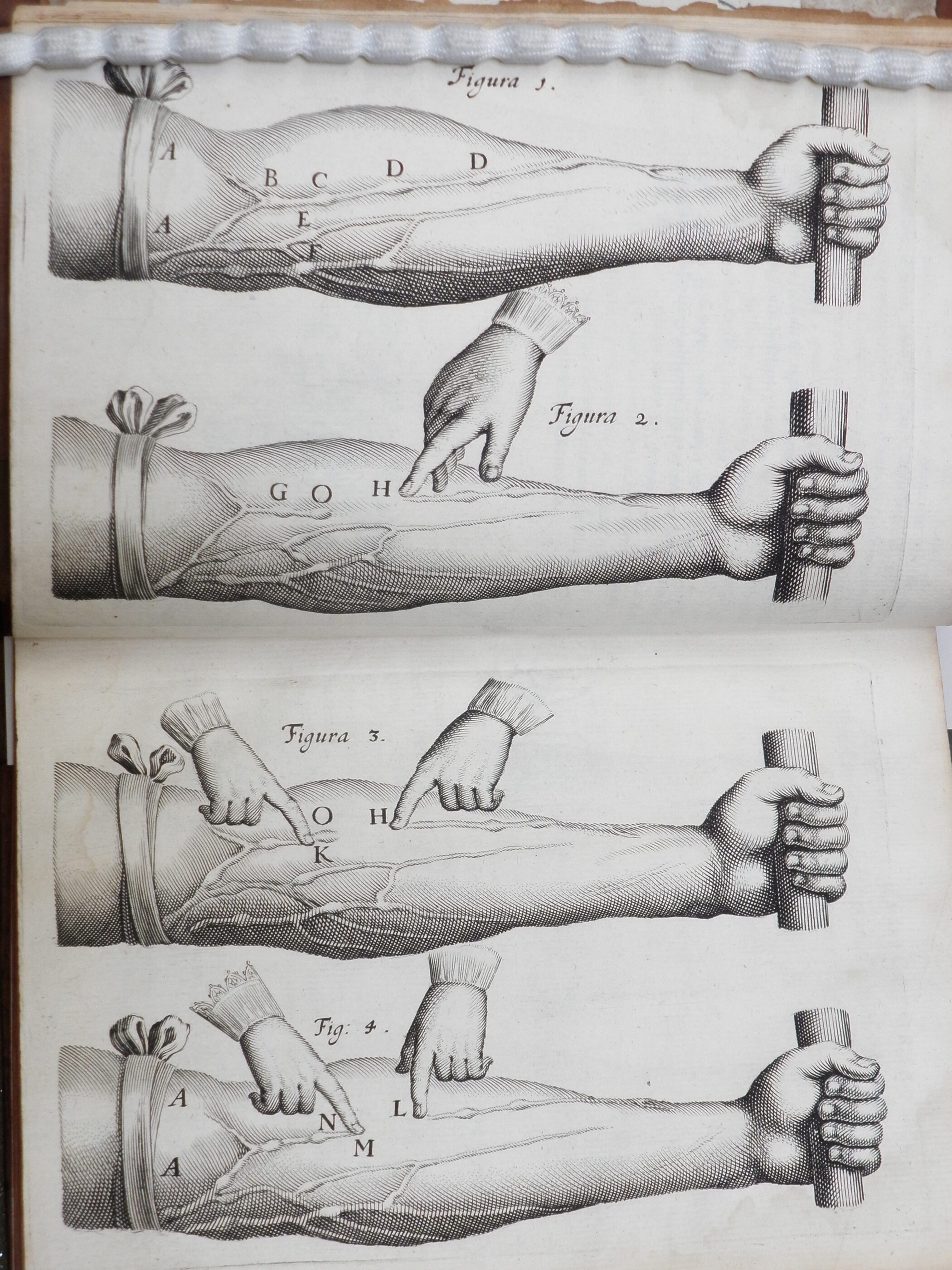

Until Harvey’s experiments in the seventeenth century, the predominant theory on the blood was still that of the classical author Galen (AD 129-c. 200 or 216). Galen thought that there were two types of blood: venous blood, generated in the liver, acted as nourishment for the parts of the body and was attracted to them when they needed food; and arterial blood, generated in the heart, which was ‘vital life-giving blood… composed of pneuma (air heated and refined in the left ventricle of the heart) and blood’ (described by Andrew Wear in his introduction to the Everyman edition of Harvey, page xviii). Given these two different types of blood with different functions, in the Galenic theory of medicine there was no conception that blood circulated, with the heart acting as a muscle in systole to force blood around the body. Harvey built on earlier discoveries and showed by experiment that ‘far too much blood left the heart in a given time for it to have been used up by the body and replaced by the blood manufactured in the liver’ (Everyman edition, page xxi); this suggested that the blood must flow in a circuit, and the famous plates, based on images from Fabricius’ De venarum ostiolis (Padua, 1603) and used from the first edition onwards, illustrate a simple experiment with ligatures which proved a connection must exist between the veins and the arteries.

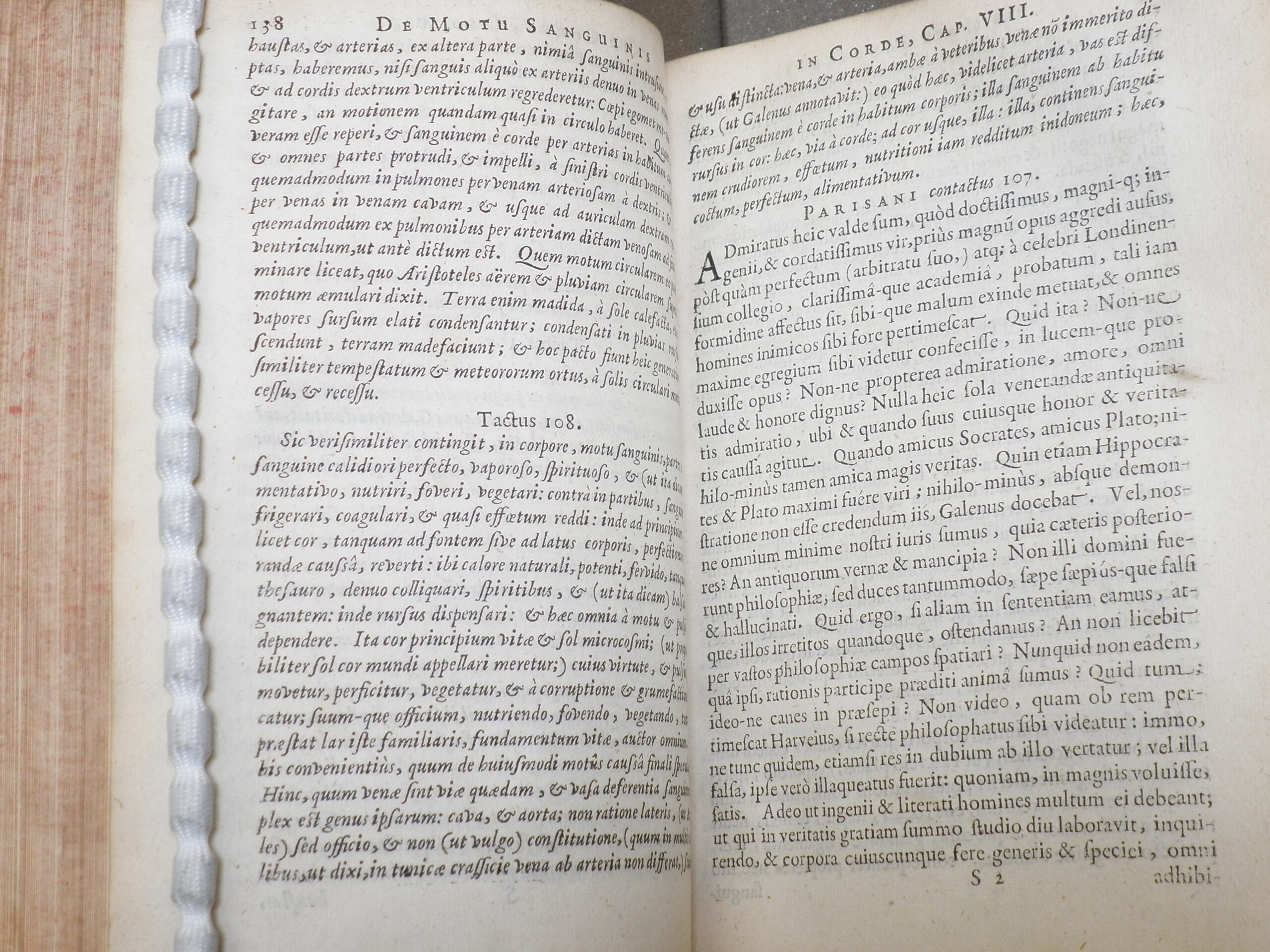

The volume at Worcester is not the first edition, published by Fitzer in Frankfurt in 1628 (see Weil, ‘William Fitzer…’, who notes (at page 145) that the Frankfurt edition is a ‘rather badly produced book… most of the copies are printed on thin, unsightly paper, now browned, in an indifferent type’), but rather the sixth edition to be printed in the seventeenth century (no. 6 in Keynes’ Bibliography), published in Leiden by Joannes Maire (c.1576/78 – 1666) in 1647. This edition prints not just the 1628 text, but includes with it several of the responses (both positive and negative) to Harvey’s work, illustrating the debate his theory generated. Harvey’s text itself is printed in alternate paragraphs with the refutations of Parisanus: Harvey’s text is in italics, Parisanus’ refutation in roman letter, here illustrated from Chapter 8 of De motu cordis, where Harvey gives his account of the sequence of thoughts that led him to believe that the blood ‘might have a certain movement, as it were, in a circle’ (‘motionem quondam quasi in circulo haberet’; for discussion of the translation of this passage, see Bates, ‘Harvey’s account of his discovery’).

As a Leiden publication, this is a high-quality quarto book, printed to a high standard on good quality paper with fine typography. One can note, for example, the embellishments in the roman type, particularly at the end of sentences or lines: an ‘e’ with extended terminal; the extended cross stoke of the ‘t’; ‘r’ with a swash when at the end of a sentence.

After the foundation of its university in 1575 (which boasted one of the first anatomical theatres in Europe and where clinical medical training was provided from 1636 onwards) Leiden’s book trade had developed greatly, benefiting from the city’s increasing status as a centre of late humanism (see Prögler, English students at Leiden University). It attracted many international visitors, such as the diarist John Evelyn in 1641, who referred to ‘that renowned University of Batavia’. George Clarke in his autobiography tells us that he visited the Low Countries in 1706, although he does not mention Leiden among cities such as Amsterdam, Utrecht, and Rotterdam which he did visit. It is, of course, possible that he acquired this volume on that trip, but whatever the means of its acquisition, Harvey’s De motu cordis would have been a necessary purchase for anyone interested in the intellectual climate of the seventeenth century.

Mark Bainbridge, Librarian

Bibliography

- Bates, D.G., ‘Harvey’s account of his “discovery”’, in Medical History 36 (1992), pages 361-378

- French, R., ‘Harvey, William (1578–1657)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2004) [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/12531, accessed 30 June 2016]

- Harris, J. and A. A. Tait, Catalogue of the drawings by Inigo Jones, John Webb and Isaac de Caus at Worcester College Oxford (Oxford, 1979)

- Harvey, W., The circulation of the blood and other writings, translated by K. J. Franklin, introduction by A. Wear, Everyman edition (London, 1993)

- Keynes, G., A bibliography of the writings of Dr William Harvey 1578-1657, 3rd revised edition (Winchester, 1989)

- Prögler, D., English students at Leiden University, 1575-1650 (Farnham, 2013)

- Weil, E., ‘William Fitzer, the publisher of Harvey’s De motu cordis, 1628’, in The Library 24 (1944), pages 142-164