Shakespeare and a Trio of Folios

23rd April 2016

Shakespeare and a Trio of Folios

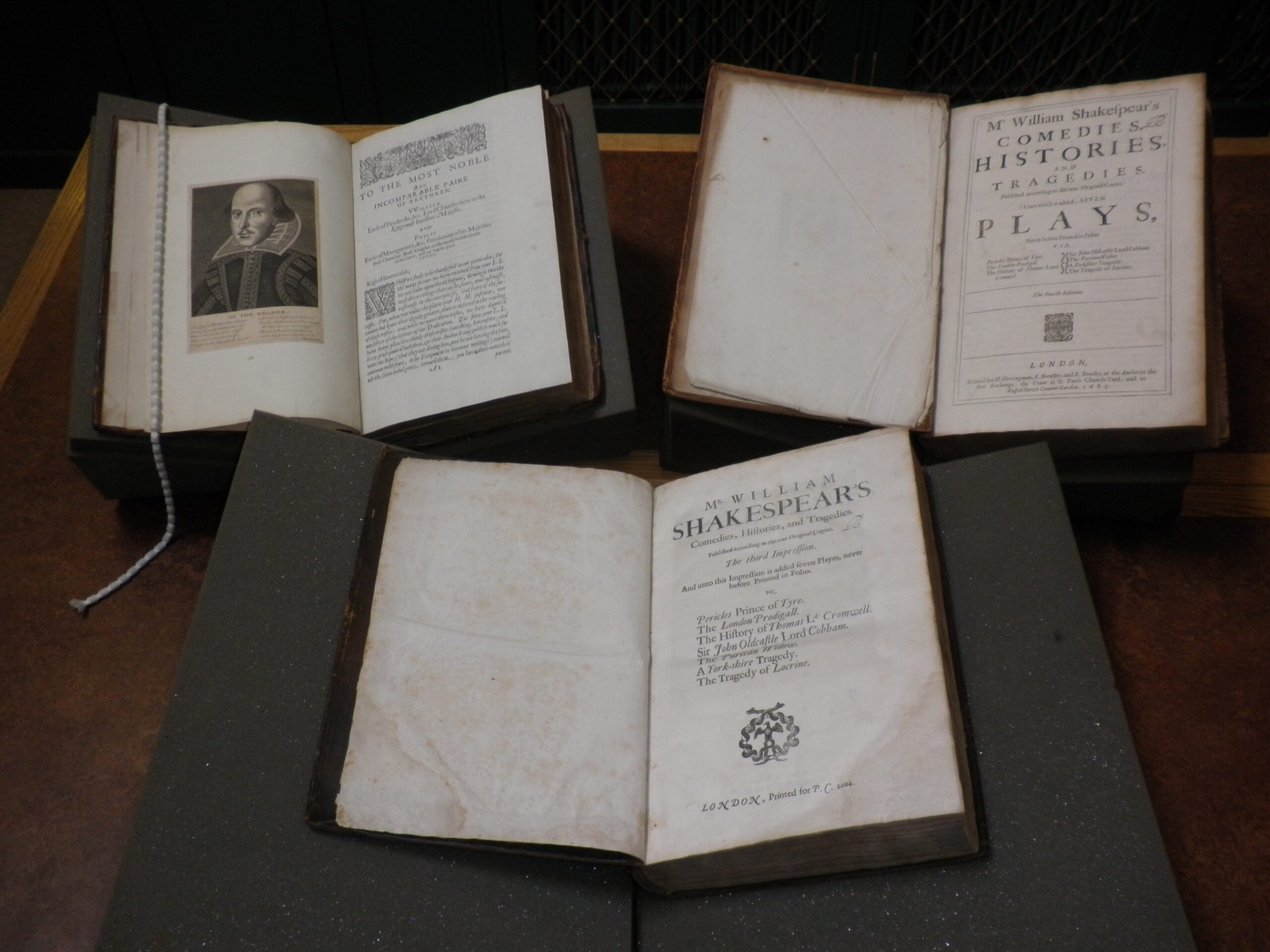

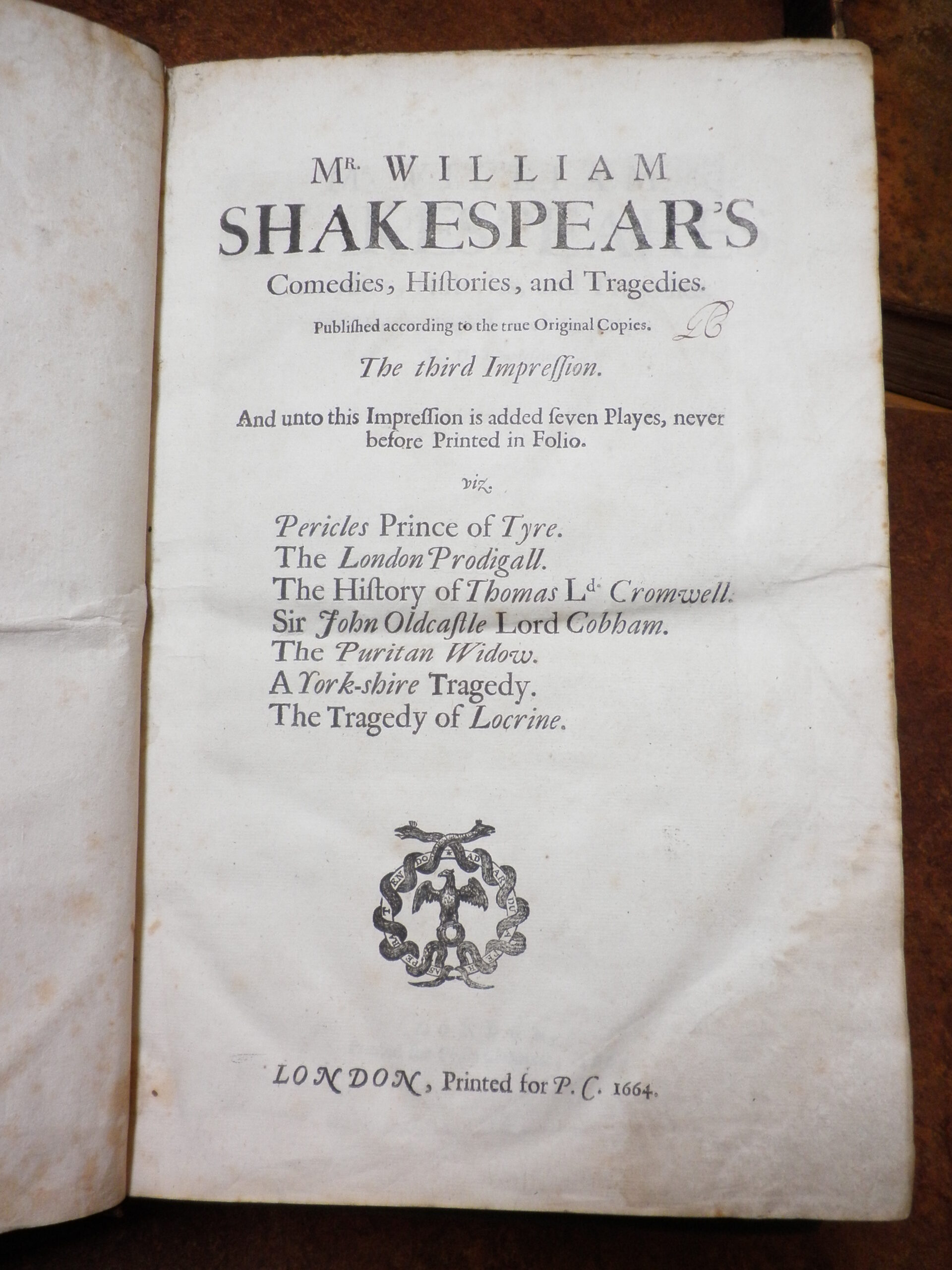

Mr. William Shakespear’s comedies, histories, and tragedies. Published according to the true original copies. The third impression. And unto this impression is added seven playes, never before printed in folio. viz. Pericles Prince of Tyre. The London prodigall. The history of Thomas Ld. Cromwell. Sir John Oldcastle Lord Cobham. The Puritan widow. A York-shire tragedy. The tragedy of Locrine.

London : printed for P. C., 1664.

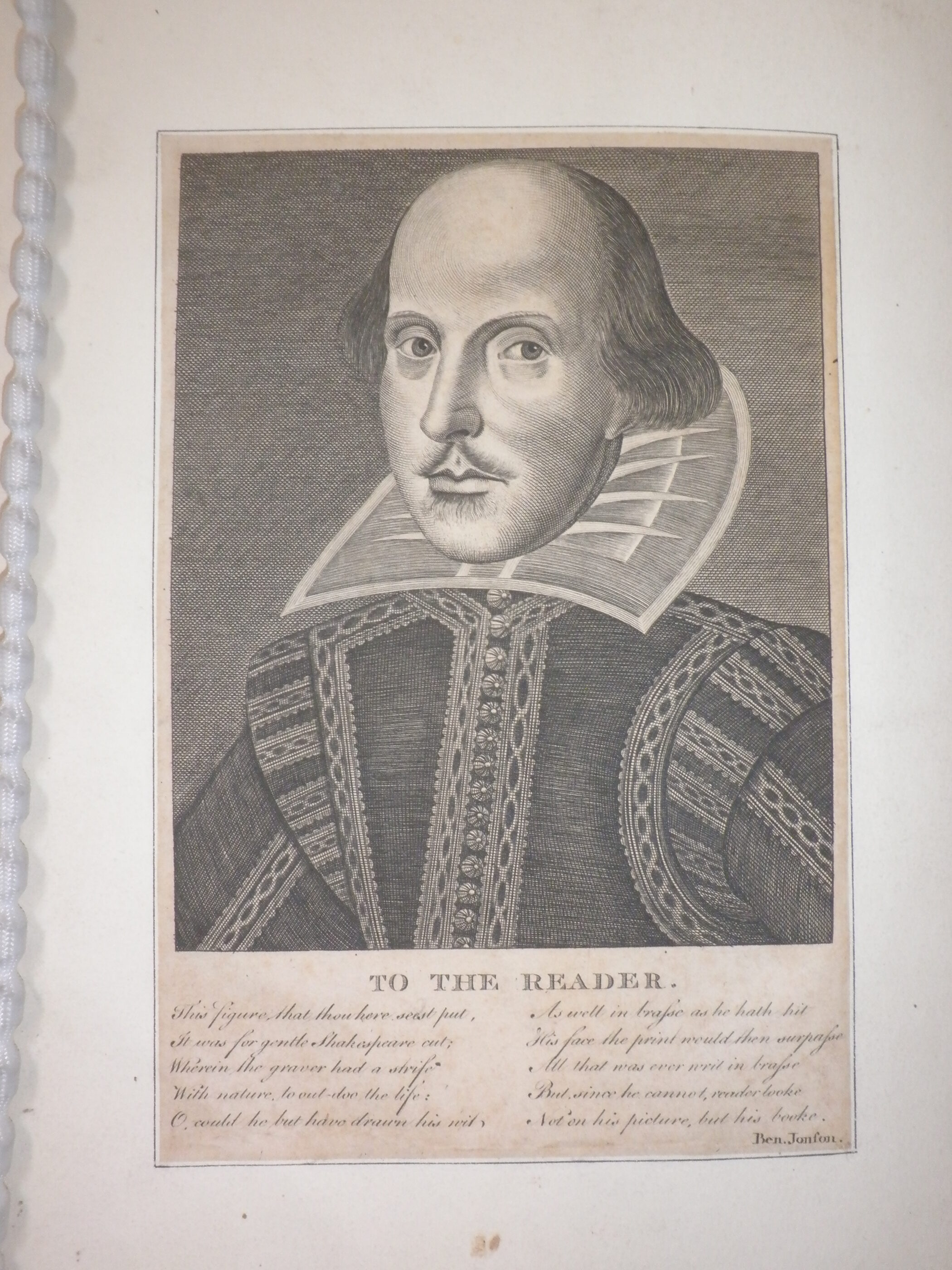

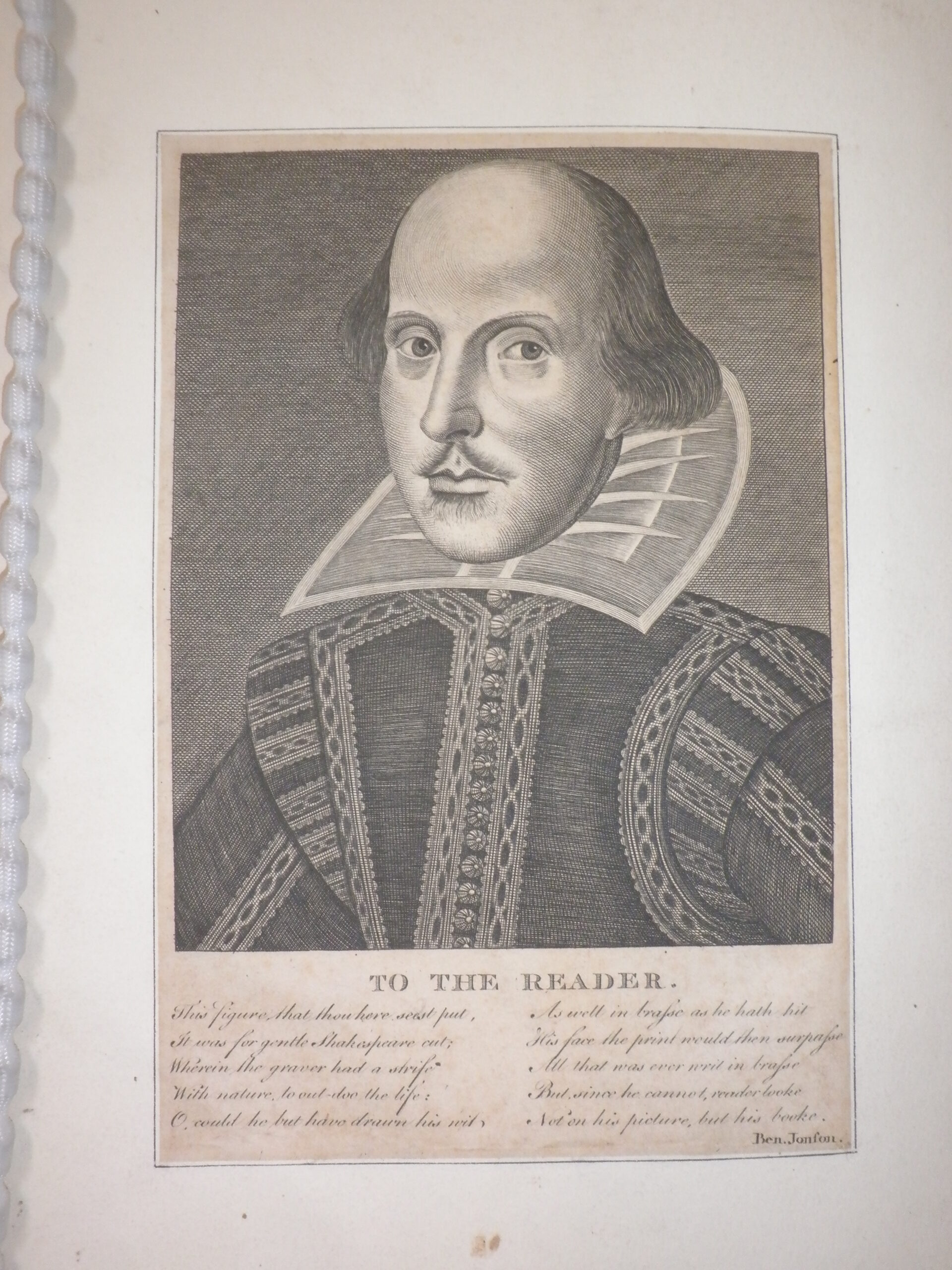

Droeshout engraving of Shakespeare, from the Worcester College copy of the Second Folio

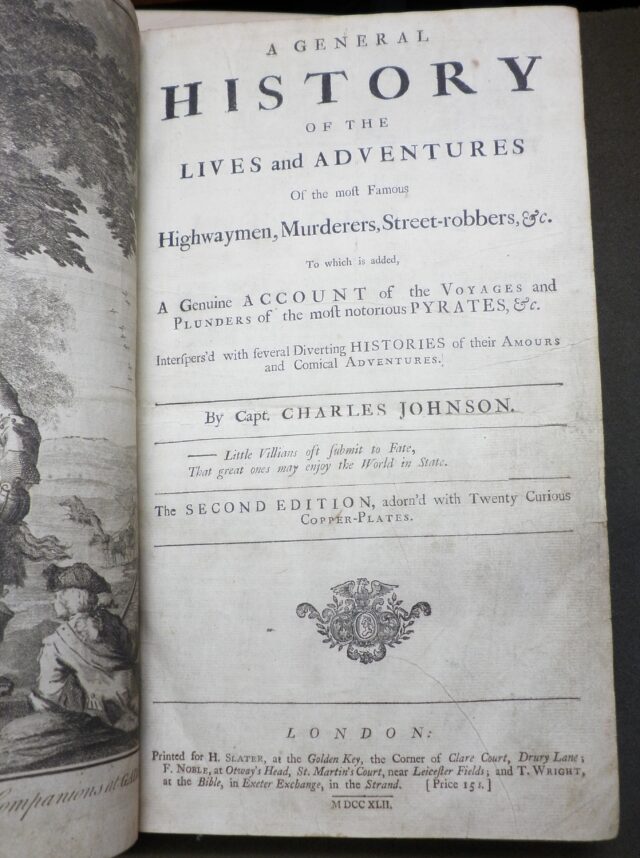

23rd April 2016 is the 400th anniversary of the death of William Shakespeare, who died in 1616. 1616 was also the year of the publication in folio of the works of Ben Jonson, the first folio publication of a playwright’s ‘collected works’. A folio (that is, a large luxury volume where the printed sheet was only folded once before being gathered and sewn into the text block) not only allowed large amounts of text to be printed in one volume, but also brought higher status, folios having traditionally been used for religious and historical works. Folio publication certainly brought greater prestige than the quarto playbooks (with sheets folded twice to produce a somewhat smaller volume) in which drama was usually published in the seventeenth century (for the low standing of drama at this time, see Smith, Shakespeare’s First Folio, pages 5-6). It was the Jonson folio that set the model for the First Folio of Shakespeare, edited by John Heminges and Henry Condell, and published seven years after the playwright’s death by William Jaggard, his son Isaac, and several other booksellers in 1623.

Much has been, and undoubtedly will be, written on the First Folio, a volume of some 950 pages and 36 plays, and the only source for eighteen of Shakespeare’s works, including some of the most popular (such as The Tempest, As You Like It, Twelfth Night, Julius Caesar, Macbeth, and Antony and Cleopatra). Worcester College Library unfortunately does not have a copy of the First Folio, but we do have copies of the Second (1632), Third (1663/1664) and Fourth Folios (1685), the three seventeenth-century volumes which sought to satisfy that century’s demand for Shakespeare (on the popularity of Shakespeare in print in the seventeenth century, see Erne, Shakespeare and the Book Trade).

The main focus of this post will be the Third Folio, a rather rare item (rarer, in fact, than the First Folio) and the first post-Restoration publication of Shakespeare. It is also the volume which added seven new plays to the collection – of which admittedly only one, Pericles, is now considered part of the Shakespearean corpus. It has been called ‘bibliographically the most confusing of the four [folios]’ (Otness, The Shakespeare folio handbook, page 7): first issued in 1663, it was reissued with a new title page in 1664, the latter issue including the seven extra plays (the Worcester copy, the 1664 issue, has both title pages). With these additional plays, the Third Folio was perhaps originally considered better value than the First: famously the Bodleian Library in Oxford de-accessioned its copy of the First Folio on receipt of the Third in 1664, having to buy back the former in 1905 (see Smith, Shakespeare’s First Folio, pages 71-2).

1664 Title Page of Third Folio

The Third Folio was published by Philip Chetwind (‘P.C.’ on the 1664 title page). The twisted serpents device with the motto ‘ad ardua per aspera tendo’ on the title page allows us to assign the printing to Robert Daniel (Pollard, Shakespeare folios and quartos, page 153), along with Alice Warren and one other. Mention of Alice Warren helps to explain the rarity of the Third Folio: the Warren printing house is known to have been destroyed by the Great Fire of London in 1666 together with many other bookshops in the vicinity of St Paul’s – it is likely that many unsold copies of the Third Folio, printed only two years before, were destroyed in the flames (see Murphy, Shakespeare in print, pages 53-54). There has been no full census of copies of the three later folios (unlike for the First, of which 232 copies were extant in 2012 – see Rasmussen and West’s descriptive catalogue), but Otness’ 1990 census of US institutional holdings does provide some illustration of the Third Folio’s scarcity: in 1990 there were only 90 copies in US institutions, compared with 134 First Folios, 178 Second Folios, and 159 Fourth Folios (Otness, The Shakespeare Folio Handbook, page 65).

The Third Folio, given both its rarity and the additional plays, acts as a valuable core around which to consider the College’s two other seventeenth-century folios: the Second Folio of 1632 and the Fourth of 1685. Each of the seventeenth-century folios was essentially a reprint of its predecessor: that is, the Third Folio was a reprint of the Second Folio (plus, of course, the extra plays), the Fourth a reprint of the Third – although, somewhat amusingly, and no doubt for commercial reasons, the Fourth falsely repeats on its title page the Third Folio’s earlier claim of ‘Seven plays never before printed in Folio’ (my italics)!

Title Page of the Fourth Folio

Each subsequent folio corrects the mistakes of the previous edition, progressively modernizing the text in terms of spelling, punctuation, and typography, with far less intervention than occurred in the eighteenth century and later, when the text started to be edited by critic-editors such as Nicholas Rowe. In 1709 Rowe conflated the folio text of Hamlet with the quarto text in an attempt to reproduce the ‘true original’ (see Bate in his introduction to The RSC Shakespeare).

Consulting the three Worcester copies side by side, it is possible to compare the differences in the volumes. All three folios set the text in double columns (as was the norm for folio publication), although the Fourth’s columns are longer with more lines per page, resulting in a different page-setting from the earlier folios.

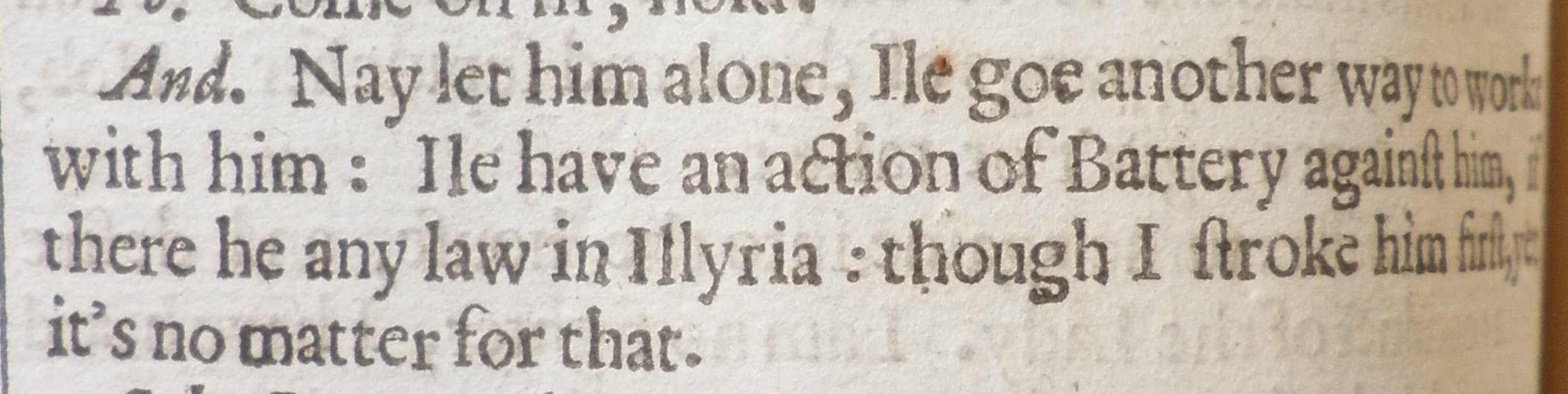

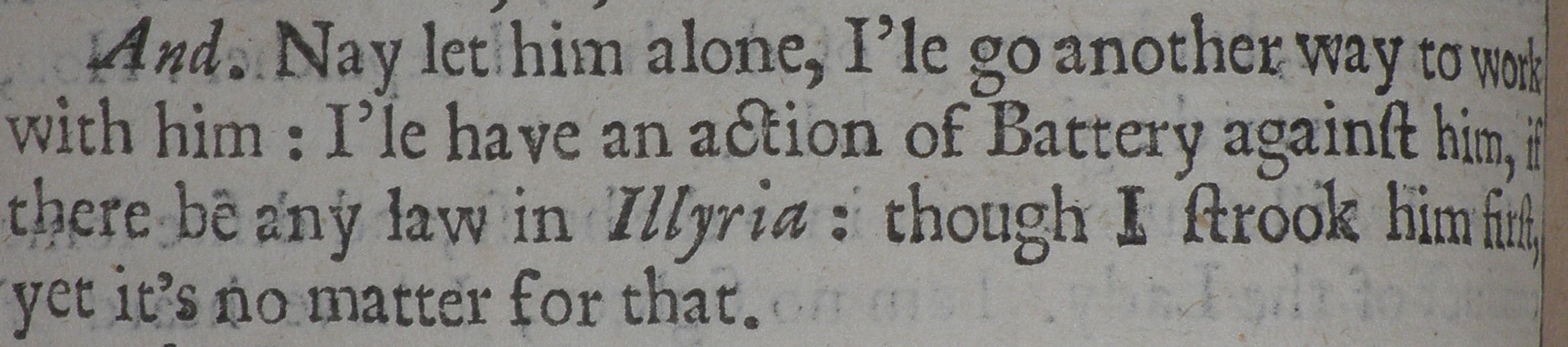

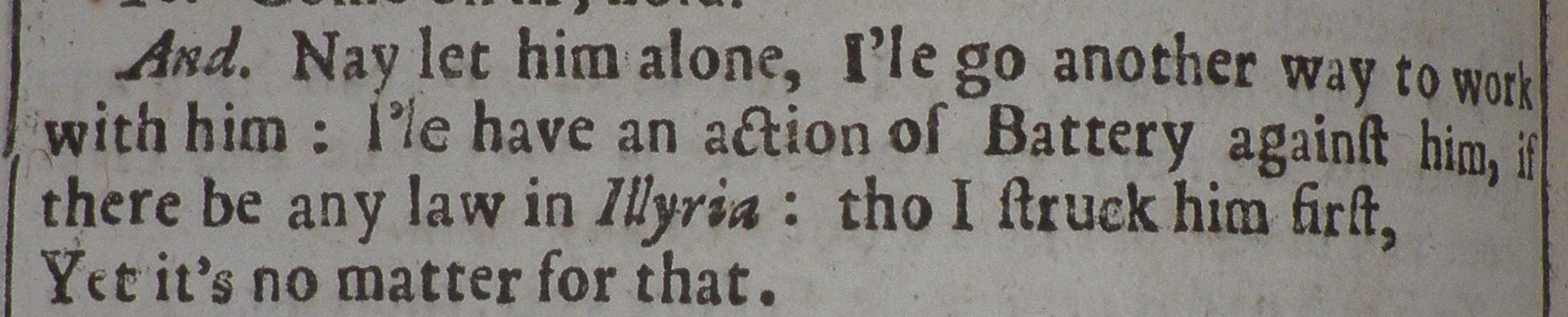

As an example of the spelling changes introduced by the printer’s correctors, who substituted more modern forms for obsolescent ones, we can look to the following passage from Twelfth Night, in particular line IV.i.34:

Second Folio

Third Folio

Fourth Folio

‘Struck’, originally spelled as ‘stroke’ in the Second Folio, becomes ‘strook’ in the Third, then ‘struck’ in the Fourth. Enabling this type of comparison is one of many reasons why the Library is fortunate to have these three folios, particularly our copy of the Third. This, like the Worcester copy of the Fourth, must have belonged to George Clarke (1661-1736) and been left to the Library in 1736: both bear his typical ‘GC’ monogram on the title page.

Mark Bainbridge, Librarian

Bibliography

- Bate, J., and Rasmussen, E. (gen. eds.), The RSC Shakespeare: William Shakespeare: complete works (Basingstoke, 2007)

- Black, M. W., and Shaaber, M. A., Shakespeare’s seventeenth-century editors, 1632-1685 (New York, 1937)

- Erne, L., Shakespeare and the book trade (Cambridge, 2013)

- Murphy, A., Shakespeare in print: a history and chronology of Shakespeare publishing (Cambridge, 2003)

- Otness, H. M., The Shakespeare folio handbook and census (New York, 1990)

- Pollard, A. W., Shakespeare folios and quartos: a study in the bibliography of Shakespeare’s plays 1594-1685 (London, 1909)

- Rasmussen, E. and West, A. J. (eds.) The Shakespeare first folios: a descriptive catalogue (Basingstoke, 2012)

- Smith, E., Shakespeare’s First Folio: four centuries of an iconic book (Oxford, 2016)