Pirates and Highwaymen: True Crime in the Eighteenth Century

15th May 2020

Pirates and Highwaymen: True Crime in the Eighteenth Century

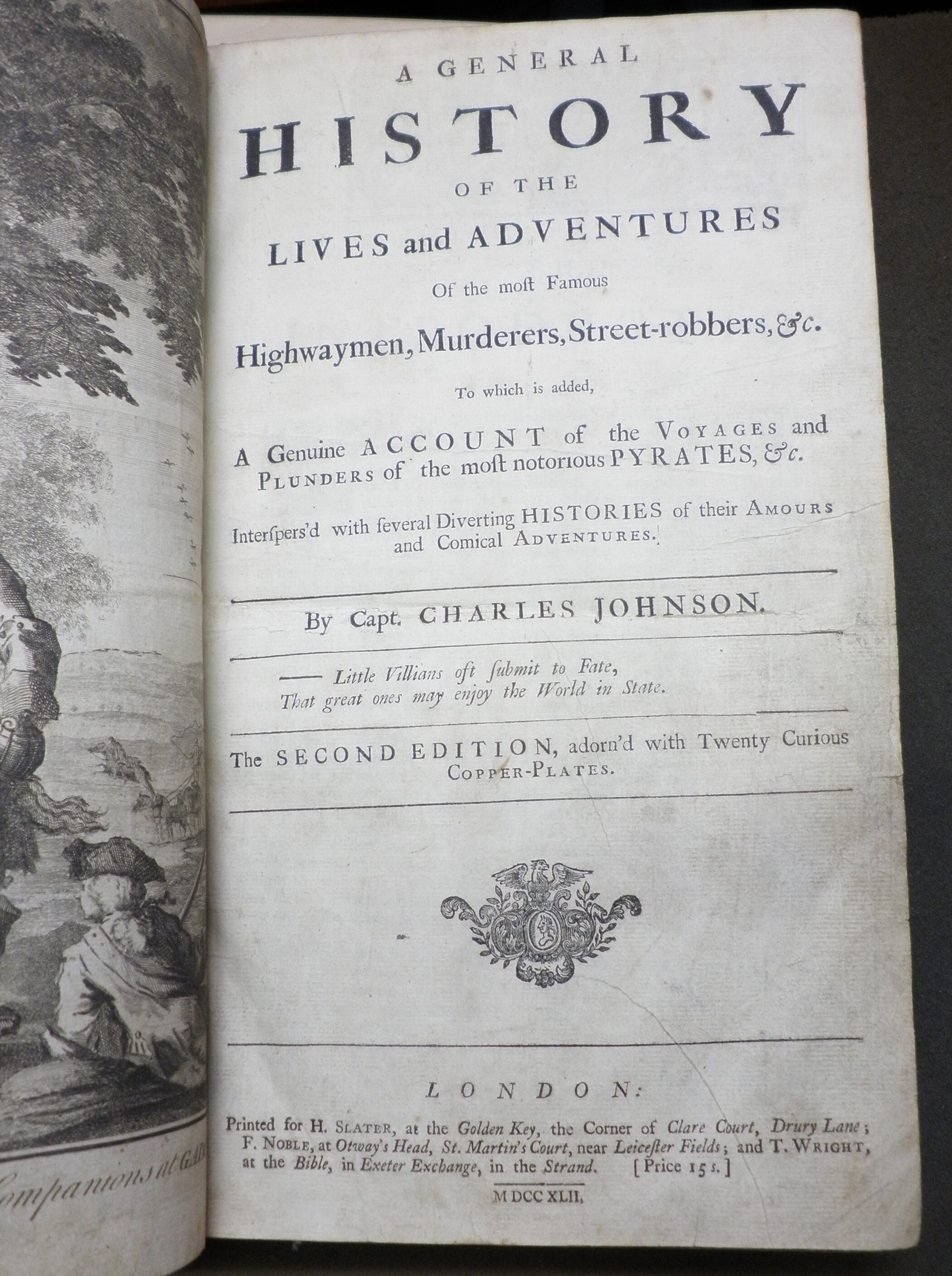

A General History of the Lives and Adventures Of the most Famous Highwaymen, Murderers, Street-robbers, &c. To which is added, A Genuine Account of the Voyages and Plunders of the most notorious Pyrates, &c. Interspers’d with several Diverting Histories of their Amours and Comical Adventures

By Capt. Charles Johnson

London: M.D.CC.XLII

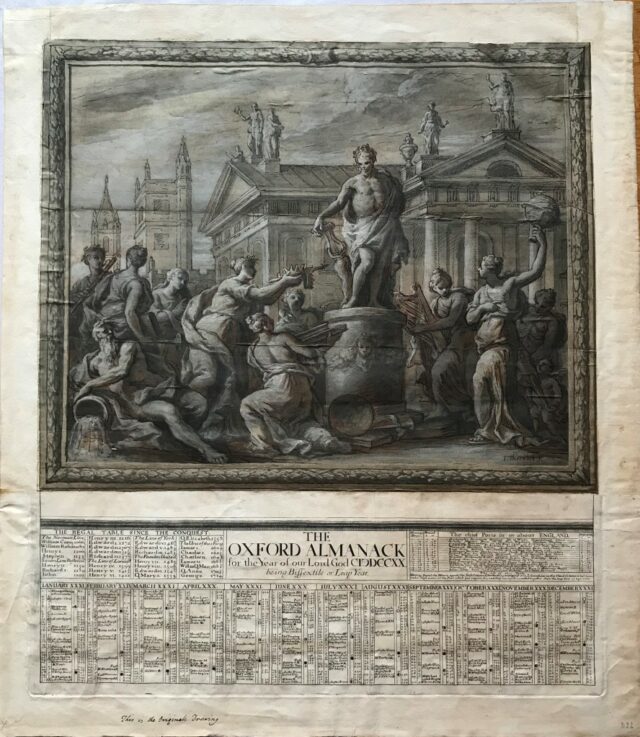

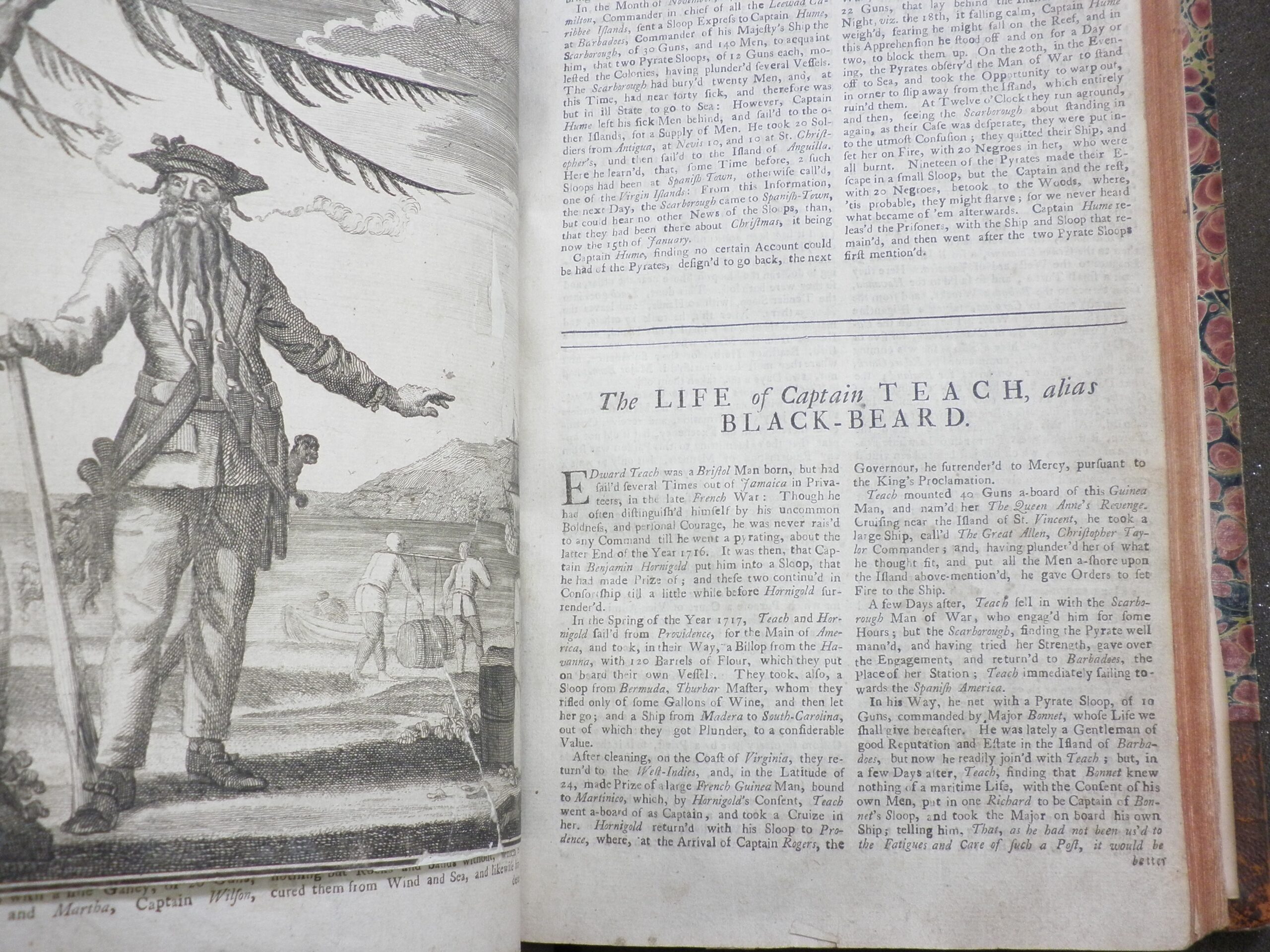

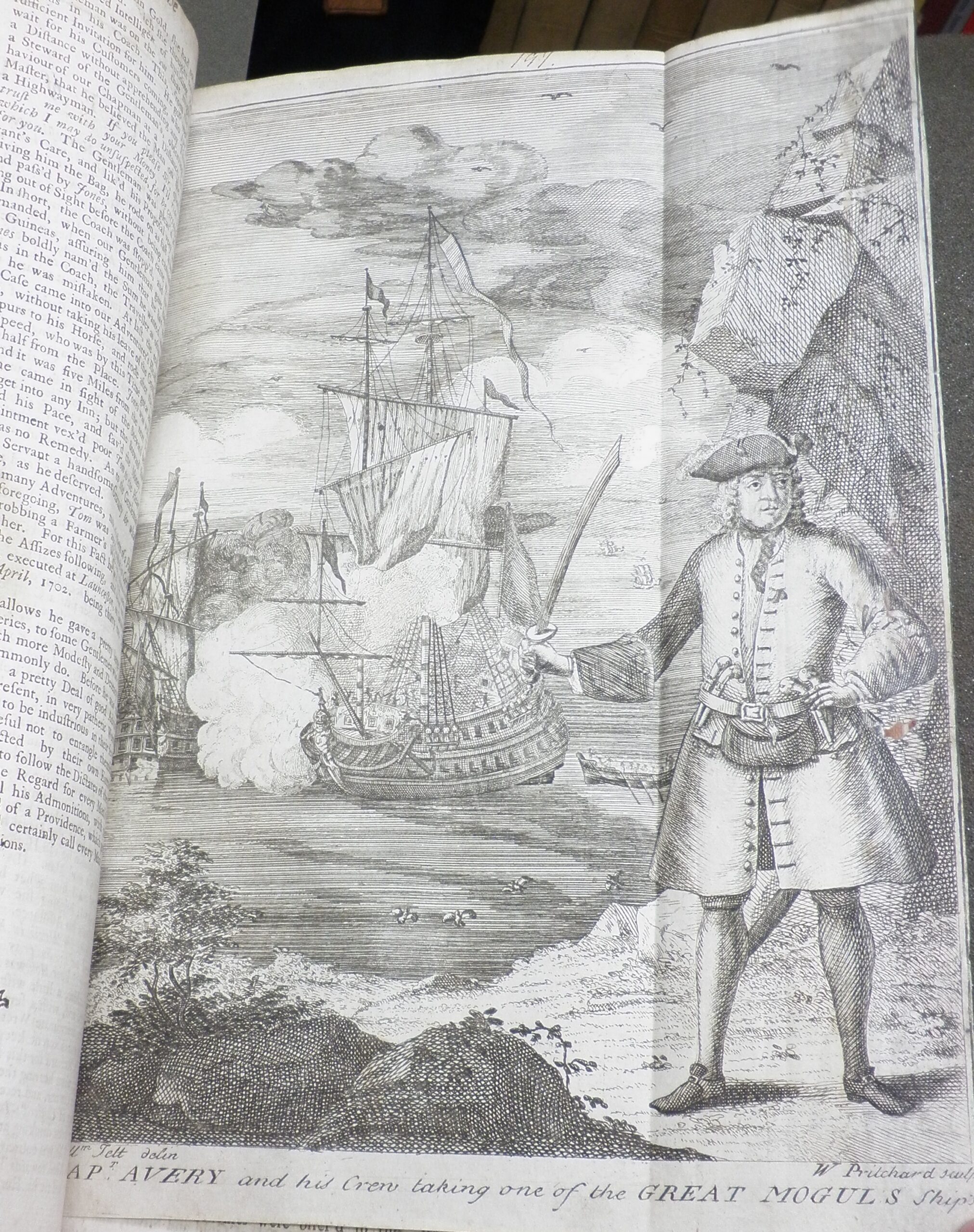

This month’s treasure is an eighteenth-century collection of tales of robbery, murder, and piracy. Captain Johnson’s General History contains dozens of biographies of the most notable criminals of the day and is one of the major sources on the ‘Golden Age of Piracy’ of the early eighteenth century, preserving for posterity the lives of figures such as Blackbeard and Anne Bonny (Arne Bialuschewski, ‘Daniel Defoe, Nathaniel Mist, and the “General History of the Pyrates”’, p. 21). A large folio volume, the General History is illustrated with ‘Twenty Curious Copper-Plates’.

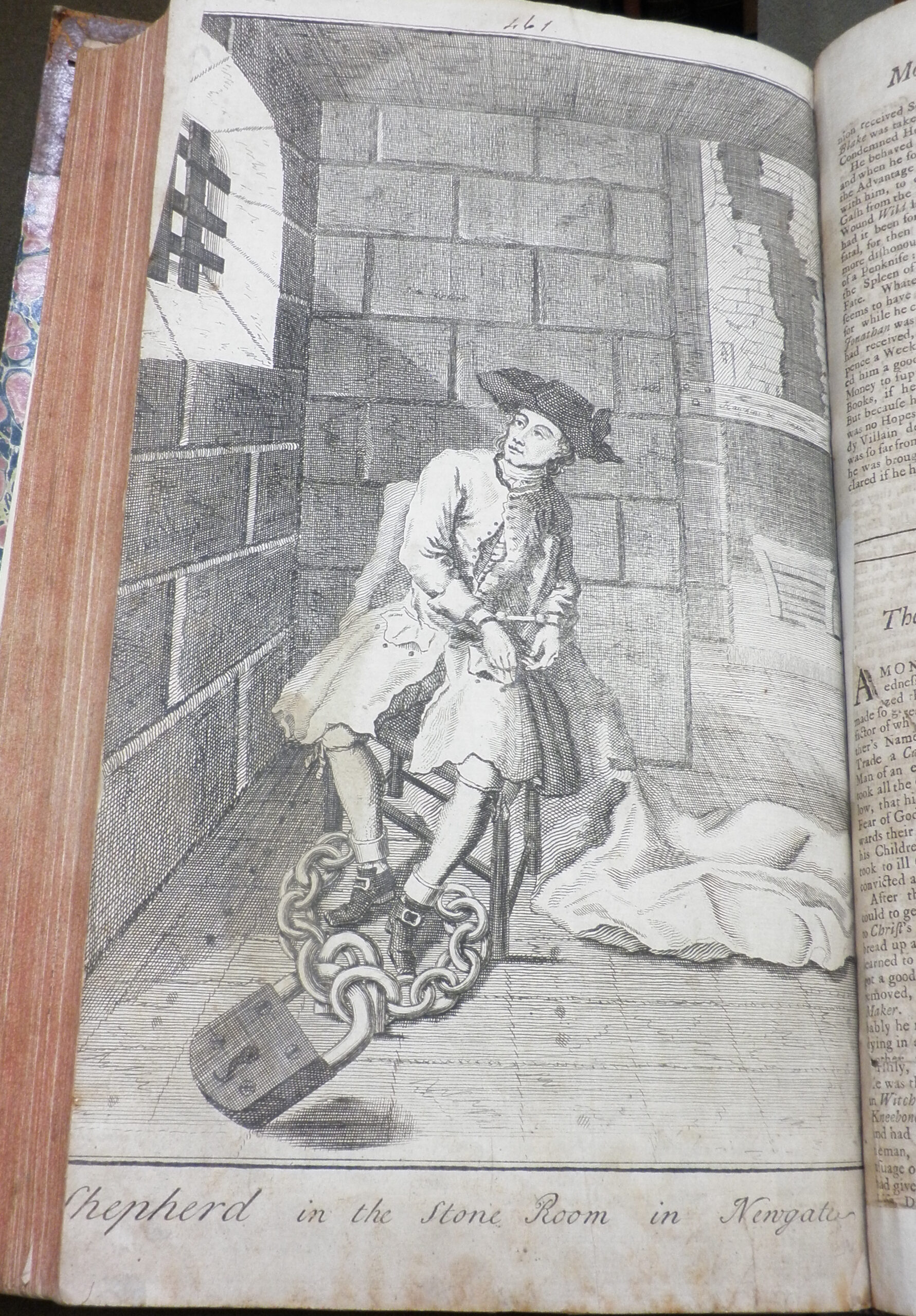

Criminal biography as a genre grew in popularity during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Accounts of trials at the Old Bailey, known as ‘sessions papers’, were published for the public, as were ‘ordinary’s accounts’ – the stories of prisoners’ last days (and, usually, rediscovery of religion) as told by the chaplain in Newgate Prison (Lincoln B. Faller, Crime and Defoe: a New Kind of Writing, pp. 4-5). In the early eighteenth century collections of criminals’ lives such as this one started to appear. Generally criminal biographies were divided into two broad categories. On one side were serious and moralistic stories, which sought to discourage a life of crime by describing the chain of poor decisions and immoral behaviour which had led to the criminal’s unfortunate end. On the other were more romantic and frivolous biographies (generally of thieves rather than murderers), which focused on entertaining anecdotes from criminals’ lives and works (Faller, Crime and Defoe, p. 6, p. 17). The extent to which these biographies were factual is debateable; while most of the people were historical figures and contemporary press accounts of their crimes would have been available to the authors, it seems likely that the authors embroidered the details of the lives rather heavily to serve their own purposes of instruction or entertainment (for more on authenticity in criminal biography, see Faller, Crime and Defoe, pp. 23-29; and on Johnson particularly, Frohock, ‘Satire and Civil Governance in A General History of the Pyrates (1724, 1726)’).

The General History contains a mixture of both serious and frivolous biographies. The account of Captain John Jaen, for example, who was convicted of beating his cabin boy to death, makes for grim reading. After his execution, Jaen’s body was displayed over the King’s Powder-House, as a

‘Warning to Others who serve in the same Station, how they abuse the great Power, with which ’tis necessary they should be invested while abroad… but of which ’tis the Privilege of those that serve under them to require an Account when they come home, that so no Subject of Great Britain may be oppressed, much less murder’d, by another entrusted with a greater Share of Authority.’ (Johnson, A General History (1734), p. 306)

The stories of pirates, such as Captain Avery and Blackbeard, often focus on their treacherous behaviour toward fellow pirates – pirates, it seems, were rather fond of marooning their co-conspirators on deserted islands and sailing away with the loot.

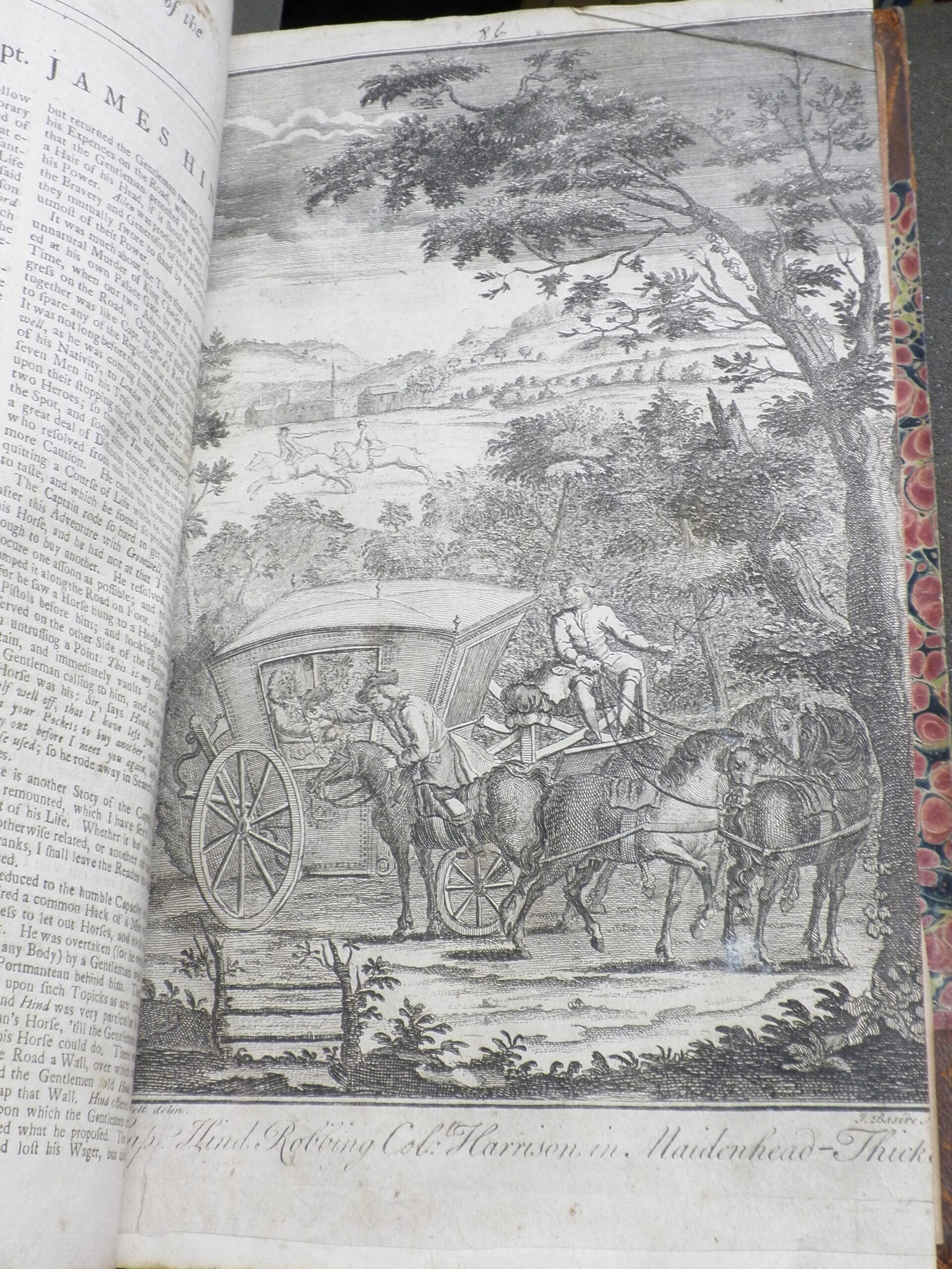

Yet at the other end of the spectrum we have stories such as the life of Captain James Hind (d. 1652), who was ‘distinguished by his Pleasantry in all his Adventures ; for he never in his Life robb’d a Man, but at the same Time he either said or did something that was diverting’ (Johnson, A General History (1734), p. 86). The General History portrays Hind as a royalist thief with a heart of gold, who only stole from regicides and the rich, and was always most gentlemanly when robbing ladies. In the end he was executed for treason rather than robbery, following a spell in the Royalist army (Johnson, A General History (1734), p. 89). James Sharpe describes Hind as the ‘prototype cavalier highwayman’, a stereotype which gained popularity in the eighteenth century and appears in romantic fiction to this day (James A. Sharpe, Crime in Early Modern England 1550-1750, p. 229).

The variations in tone throughout this collection may be in part because our edition is actually a combination of two works which were originally published separately: Johnson’s A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the most Notorious Pyrates (1724) and A Complete History of the Lives and Robberies of the most Notorious Highwaymen (1714) by Alexander Smith (H.R. Tedder/David Cordingly, ‘Johnson, Charles (fl. 1724-1734)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography). There is an air of mystery to these collections as both Charles Johnson and Alexander Smith appear to have been pseudonyms, and their true identities have never been indisputably established. The identity of Captain Johnson has in fact been a topic of debate amongst literary scholars for the better part of a century.

In 1932 John Robert Moore, a prominent Daniel Defoe scholar, attributed Johnson’s work to Defoe. This attribution stood until the late 1980s, when P.N. Furbank and W.R. Owens challenged it on the basis that the attribution was based solely on Moore’s ‘intuitive recognition’ of Defoe’s style, rather than on any documentary evidence (Bialuschewski, ‘Daniel Defoe’, p. 22). It is generally agreed that Johnson’s biographies of pirates show a familiarity with the sea and the West Indies, so it is likely that Captain Johnson was a seaman of some sort (Tedder/Cordingly, ‘Johnson, Charles’). In an article from 2004, Arne Bialuschewski argues convincingly for the work to be attributed to Nathaniel Mist (d. 1737), a sailor turned printer and journalist, whose Jacobite tendencies and borderline seditious press led to frequent skirmishes with the law and eventual exile in France (for more please see Bialuschewski, Arne, ‘Daniel Defoe, Nathaniel Mist, and the “General History of the Pyrates”’). However, the jury is still out on the question of Johnson’s true identity and it seems unlikely that the mystery will ever be indisputably solved.

*Note: although the images in this post have been taken from the 1742 edition in Worcester College Library, quotations are from the 1734 edition digitised by ECCO (reference below), as I was unable to access the print copy while writing.

Renée Prud’Homme, Assistant Librarian

Bibliography

- Bialuschewski, Arne, ‘Daniel Defoe, Nathaniel Mist, and the “General History of the Pyrates”’, The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, vol. 98 no. 1 (March 2004), pp. 21-38, JSTOR [Accessed online: 15 April 2020]

- Faller, Lincoln B., Crime and Defoe: a New Kind of Writing (Cambridge: CUP 1993), ACLS Humanities [Accessed online: 26 March 2020]

- Frohock, Richard, ‘Satire and Civil Governance in A General History of the Pyrates (1724, 1726)’, The Eighteenth Century, Vol. 56 No. 4 (Winter 2015), pp. 467-483, Project Muse [Accessed: 11 May 2020]

- Johnson, Charles, A general history of the lives and adventures of the most famous highwaymen, murderers, street-robbers, &c. To which is added, a genuine account of the voyages and plunders of the most notorious pyrates. Interspersed with several diverting Tales, and pleasant Songs. And Adorned with the Heads of the most Remarkable Villains, Curiously Engraven on Copper. By Capt. Charles Johnson (London, M.DCC.XXXIV [1734]), Eighteenth Century Collections Online, Gale [Accessed online: 7 May 2020]

- Rogers, Pat, “Smith, Alexander (fl. 1714–1726), compiler of biographies”, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 23 Sep. 2004 [Accessed online: 8 May 2020]

- Sharpe, James A., Crime in Early Modern England 1550-1750 (2nd ed. London: Routledge, 1999) [Accessed online: 9 April 2020]

- Tedder, H. R. and David Cordingly, “Johnson, Charles (fl. 1724–1734), author”, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 23 Sep. 2004 [Accessed online: 8 May 2020]