“They were made for singin’ an’ no for readin’!”

31st January 2017

“They were made for singin’ an’ no for readin’!”

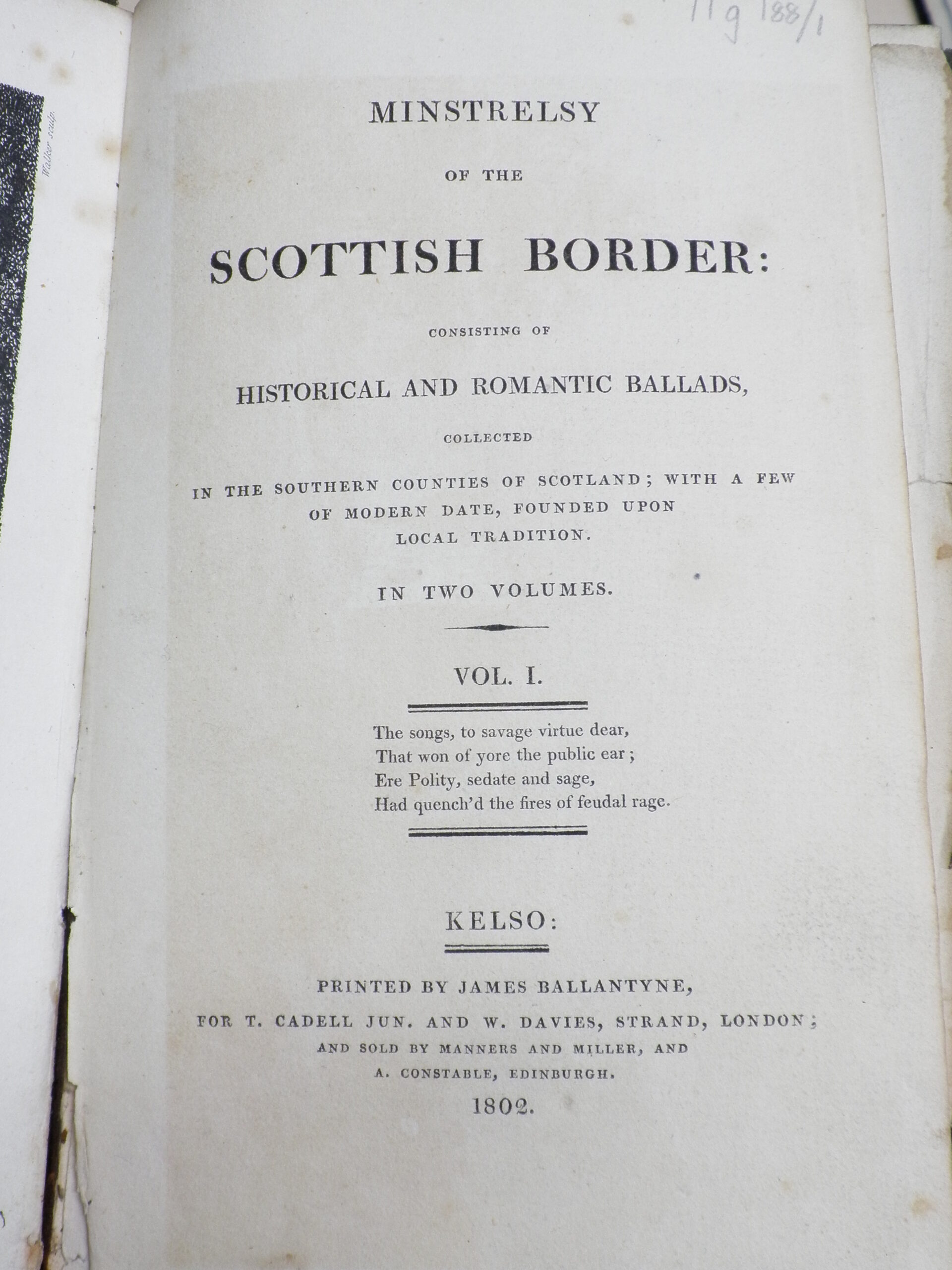

Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border: consisting of historical and romantic ballads, collected in the southern counties of Scotland; with a few of modern date, founded upon local tradition.

In two volumes, Kelso: printed by James Ballantyne, for T. Cadell, Jun. and W. Davies, Strand, London… 1802

With the pipe tunes of Burns’ Night celebrations still ringing in our ears, we decided this month to look at something from our small collection of items relating to Scottish music. The Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border was compiled and edited by Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832) and was his first major literary work (McNeil, ‘Ballads and Borders’, p. 22). The first edition in 1802 contained 52 ballads, along with extensive prefatory material on the Borders region. Scott added material to later editions; a second edition in 1803 contained 86 ballads over three volumes, the 1806 edition had 90, and the 1812 edition had 96 (Hewitt, ‘Scott, Sir Walter’, ODNB). The first volume of the first edition begins with a 138-page introduction by Scott on the history, customs, and folklore of the Scottish Borders. As well as a rather romantic history of the region, with extensive coverage of great deeds by the ancestors of his patron, the Duke of Buccleuch (who, incidentally, were Scott’s ancestors as well, {McNeil, ‘Ballads and Borders’, p. 31}), he writes on cattle thieving, spirits and sprites, and of course, balladry and minstrelsy. The introduction is adorned with footnotes filled with local anecdotes and ghost stories. Scott divides the ballads into three categories: historical ballads, romantic ballads, and modern interpretations of ancient ballads. Many of the ballads also have their own introductions and notes, detailing the sources and contexts of the song.

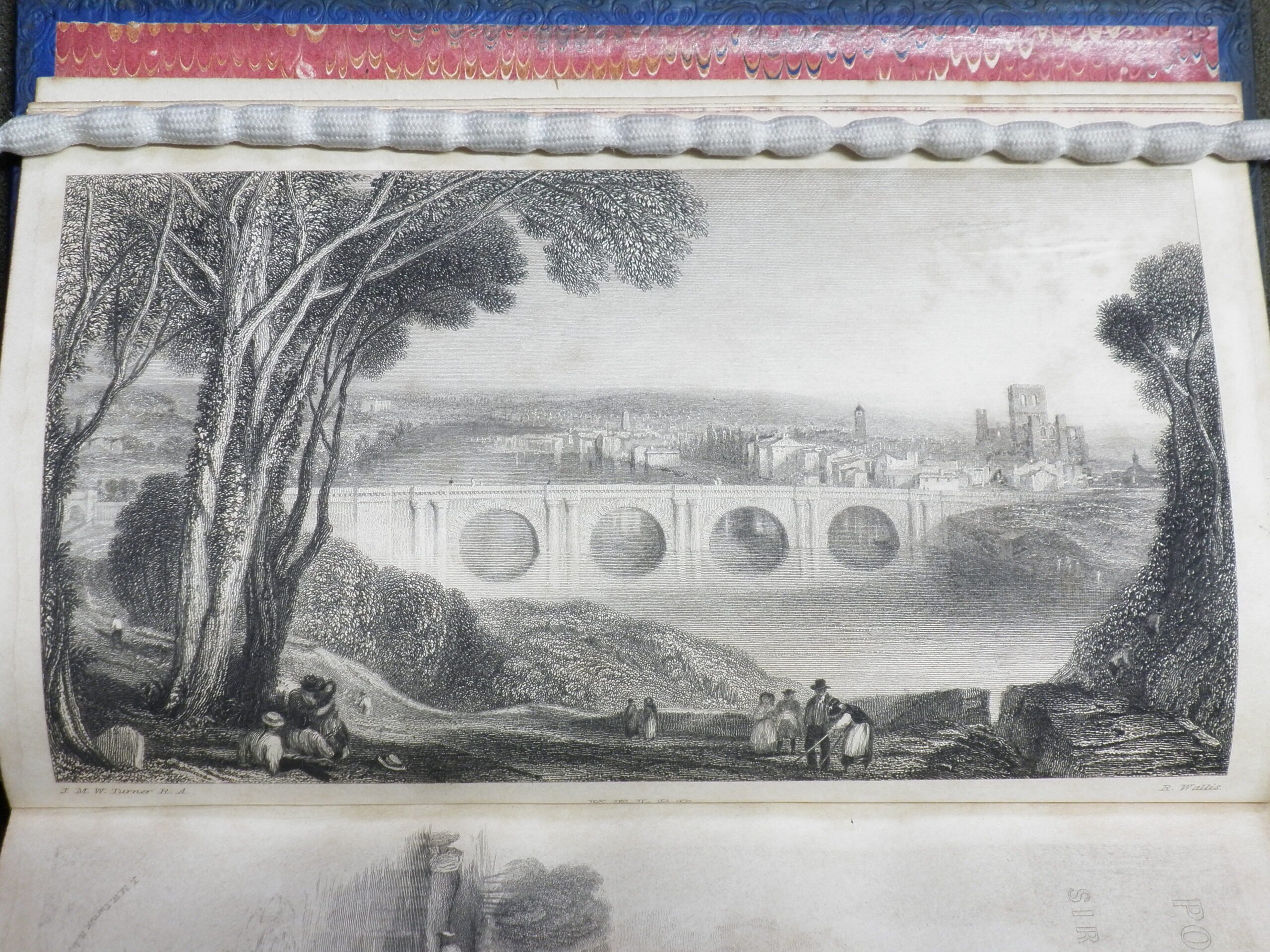

Engraving of Kelso from an 1833 edition of the Minstrelsy.

Scott acquired his ballads from a number of sources. Some he knew from his own family, having spent part of his childhood living with extended family in Sandyknowe in Roxburghshire (Hewitt, ‘Scott, Sir Walter’). He went on collecting tours of the Borders between 1792 and 1801 to acquire songs from locals. During this time he was introduced to William Laidlaw, James Hogg, and John Leyden, all of whom contributed material to the Minstrelsy, though more so in later editions (Lang, Sir Walter Scott and the Border Minstrelsy, pp. 4-5; McNeil, ‘Ballads and Borders’, p. 23; Hewitt, ‘Scott, Sir Walter’). He also took many ballads from manuscript sources, such as those of David Herd (Campbell, ‘Collectors of Scots Song’, p. 428; Collinson, The Traditional and National Music of Scotland, p. 124).

The Minstrelsy was part of the growing body of antiquarian work being written on Scotland in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Scots song and ballads began to be written down from around the 1720s by figures such as George Thomson, Allan Ramsay, David Herd, and eventually Robert Burns. Interest in Scotland’s history and traditional music grew over the course of the eighteenth-century, fuelled by works such as James MacPherson’s Ossianic Fragments (despite later controversy over their authenticity). With advancing industrialisation, there was a sense that traditional and rural cultures were disappearing and that their folklore and music needed to be preserved (McNeil, ‘Borders and Ballads’, p. 26). Scott’s Minstrelsy, with its extensive introduction, footnotes, and appendices, was part of this antiquarian collecting trend, but it was also very influential in literary circles (McNeil, ‘Ballads and Borders’, p. 26; Johnson, Music and Society in Lowland Scotland, p. 146).

Engraving of Caerlaverock Castle from an 1833 edition of the Minstrelsy.

For all his good intentions, Scott and the Minstrelsy have been subject to criticism from the beginning. One major area of contention is Scott’s approach to editing. He did not print the ballads faithfully word for word as sung or recited to him. Instead, he tended to tidy them up for publication, adding lines or stanzas here or there. He also combined different versions of the same ballad, choosing which parts of each version he thought best (Lang, Sir Walter Scott, pp. 8-10; Hewitt, ‘Scott, Sir Walter’). Scott made no secret of his editorial approach. In the introduction to the first volume, he writes:

‘No liberties have been taken either with the recited or written copies of these ballads, farther than that, where they disagreed, the editor, in justice to the author, has uniformly preserved what seemed to him the best or most poetical reading of the passage… Some arrangement was also occasionally necessary to recover the rhyme, which was often, by the ignorance of the reciters, transposed or thrown into the middle of the line. With these freedoms, which were essentially necessary to remove obvious corruptions, and fit the ballads for the press, the editor presents them to the public, under the complete assurance, that they carry with them the most indisputable marks of their authenticity.’ (pp. cii-ciii)

The concept of ‘authenticity’ has always been problematic for antiquarians and ethnographers. Translating oral culture, and particularly music, to print is fraught with technical and interpretative issues. Words are not always fixed in oral traditions and Scottish traditional music does not fit well into classical musical notation. Modern scholars would certainly not see Scott’s approach as preserving authenticity and would record every version of a piece as found, with all inconsistencies and ‘corruptions’ intact. Scott’s methodology actually fell out of favour quite early on – it was already being criticised by William Motherwell, another song collector, in the 1820s (Lang, Sir Walter Scott, p. 14). Even Lang, who staunchly defends Scott against accusations of outright fabrication, describes his editing as ‘literary, rather than scientific’ (Lang, Sir Walter Scott, p. 7). Furthermore, Scott does not seem to have acknowledged the extent of his alterations – according to McNeil, he has been found to have added in the names of people and places where there were none, usually situating them in the Borders (‘Ballads and Borders’, pp. 28-29)!

‘Jamie Telfer of the Fair Dodhead’ is one of the ballads that scholars believe Scott added stanzas to (Lang p. 8)

Scott added notes concerning the origins of many of the ballads.

Modern scholars are not the only ones to have taken issues with Scott’s editing however. A famous and often-quoted condemnation came from James Hogg’s mother, Margaret Laidlaw, who said:

‘There war never ane o’ my sangs prentit till ye prentit them yoursel’, and ye hae spoilt them awthegither. They were made for singin’ an’ no for readin’; but ye hae broken them charm noo, and they’ll never (be) sung mair. An’ the worst thing of a’ they’re nouther richt spell’d nor richt setten down.’ (quoted in Collinson, Traditional and National Music, p. 138)

Margaret’s complaint also highlights another one of the primary criticisms of music scholars – that Scott recorded the words of the ballads without the tunes. It is well-known that Scott was not particularly musical and unlike Robert Burns, he would not have been able to record the music himself, though Collinson argues that as a number of his collaborators did have the skills to transcribe music, this was no excuse (Traditional and National Music, p. 137). He was not the first to separate lyrics from their tunes though – Allan Ramsay, an early eighteenth-century collector and publisher, set the precedent and while there were some collectors who had the sense to keep words and music together, many others did not (Collinson, Traditional and National Music, pp. 132-139). The result is that as the ballads have faded from oral memory, Scott’s versions are often the only surviving record and the tune is therefore lost.

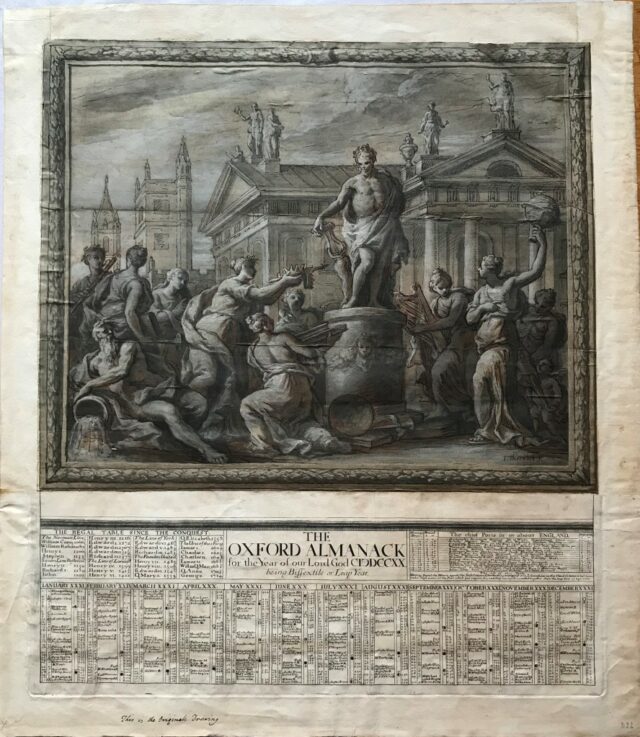

Engraving from the title page of an 1833 edition of the Minstrelsy.

For all its flaws, Scott’s Minstrelsy has managed to preserve poetic versions of ballads which otherwise might have been lost, along with bits of folklore and stories from the region. It also inspired new generations of collectors to seek out Scots song to save from extinction (Collinson, Traditional and National Music, p. 143). The material collected for the Minstrelsy also provided a rich source of inspiration for Scott’s later career as a novelist which, for better or worse, has had a profound influence on Scottish culture and literature.

Renée Prud’Homme, Assistant Librarian

Bibliography

- Campbell, Katherine, ‘Collectors of Scots Song’ in Oral Literature and Performance Culture, ed. John Beech, Owen Hand, Fiona MacDonald, Mark A. Mulhern and Jeremy Weston (Edinburgh 2007)

- Collinson, Francis, The Traditional and National Music of Scotland (London 1966)

- Hewitt, David, ‘Scott, Sir Walter (1771–1832)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2008 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/24928, accessed 30 Jan 2017]

- Johnson, David, Music and Society in Lowland Scotland in the Eighteenth Century (2nd edition Edinburgh 2003)

- Lang, Andrew, Sir Walter Scott and the Border Minstrelsy (London 1910)

- McNeil, Kenneth, ‘Ballads and Borders’ in The Edinburgh Companion to Sir Walter Scott, ed. Fiona Robertson (Edinburgh 2012), pp. 22-34

- Ragaz, Sharon Anne, ‘Ballantyne, James (1772–1833)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/1228, accessed 30 Jan 2017]