Remembering 1720 in 2020

31st July 2020

Remembering 1720 in 2020

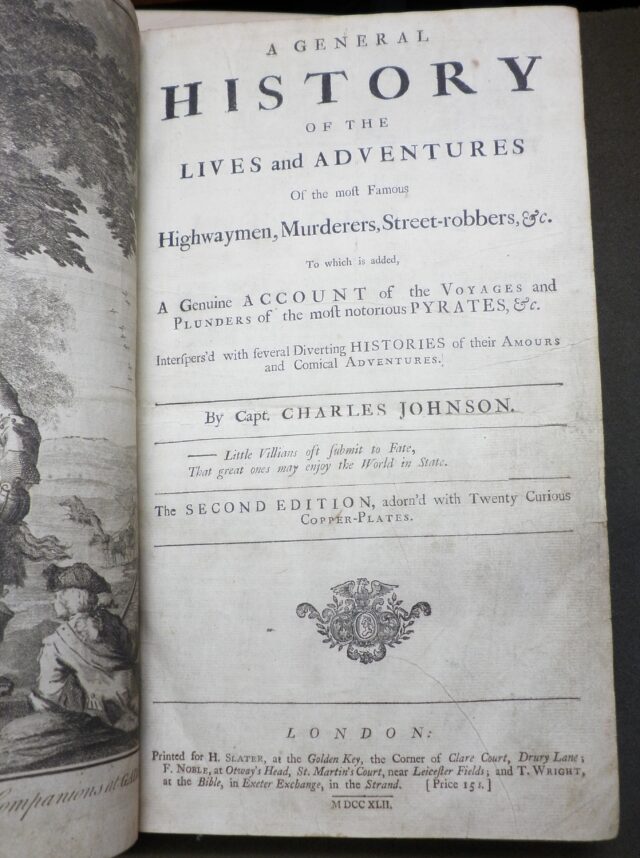

James Thornhill’s Drawing for the Oxford Almanack 1720 [Colvin 522]

2020 is certainly a year we will not forget. 1720 was perhaps less memorable – although it was the year of the South Sea Bubble (see our blog post for July 2016)! – but the Library collections hold a remarkable object linked to that year: James Thornhill’s original drawing for the Oxford Almanack of 1720 (see featured image).

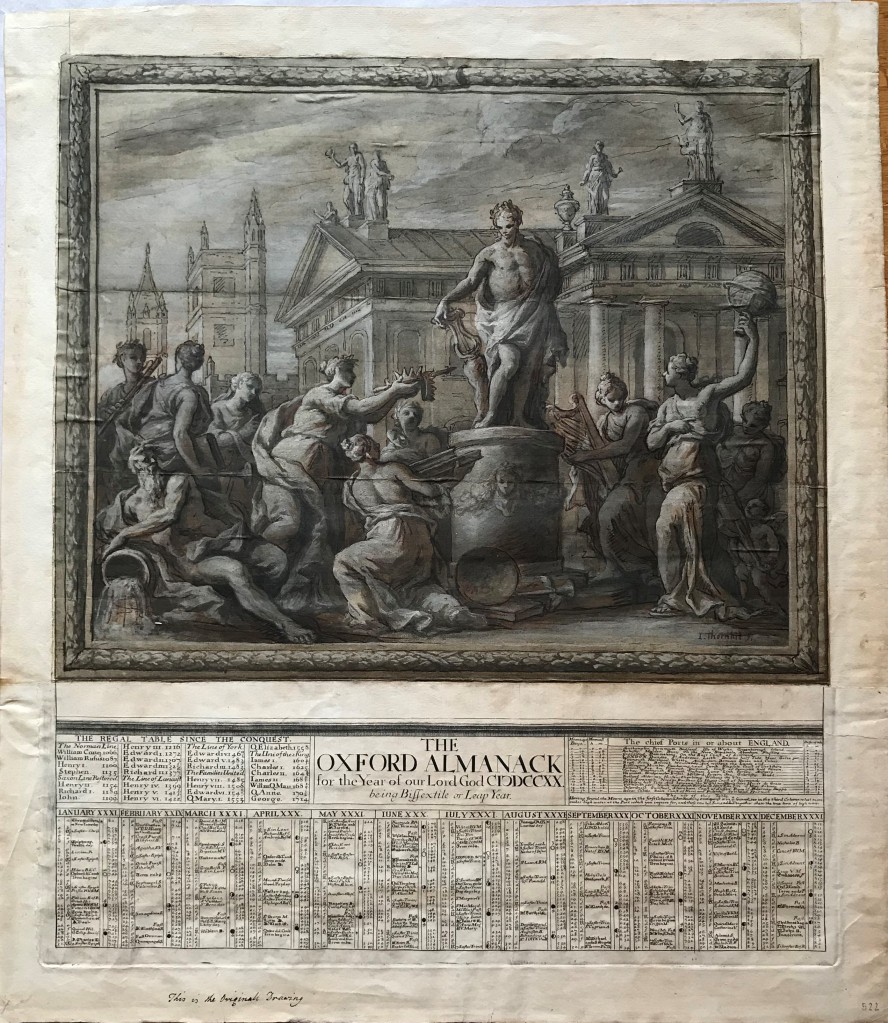

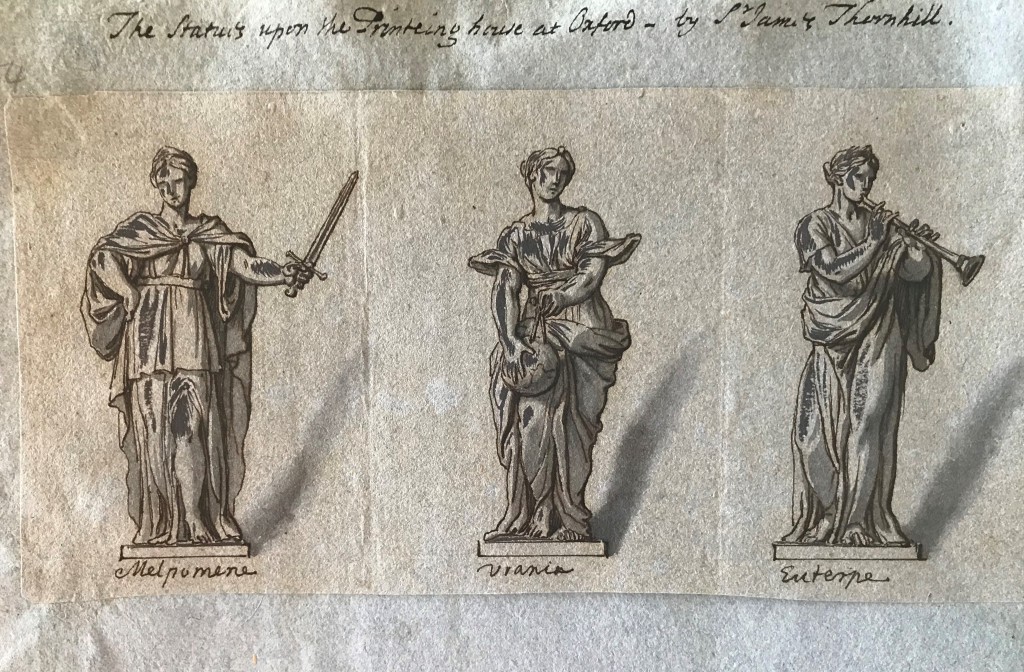

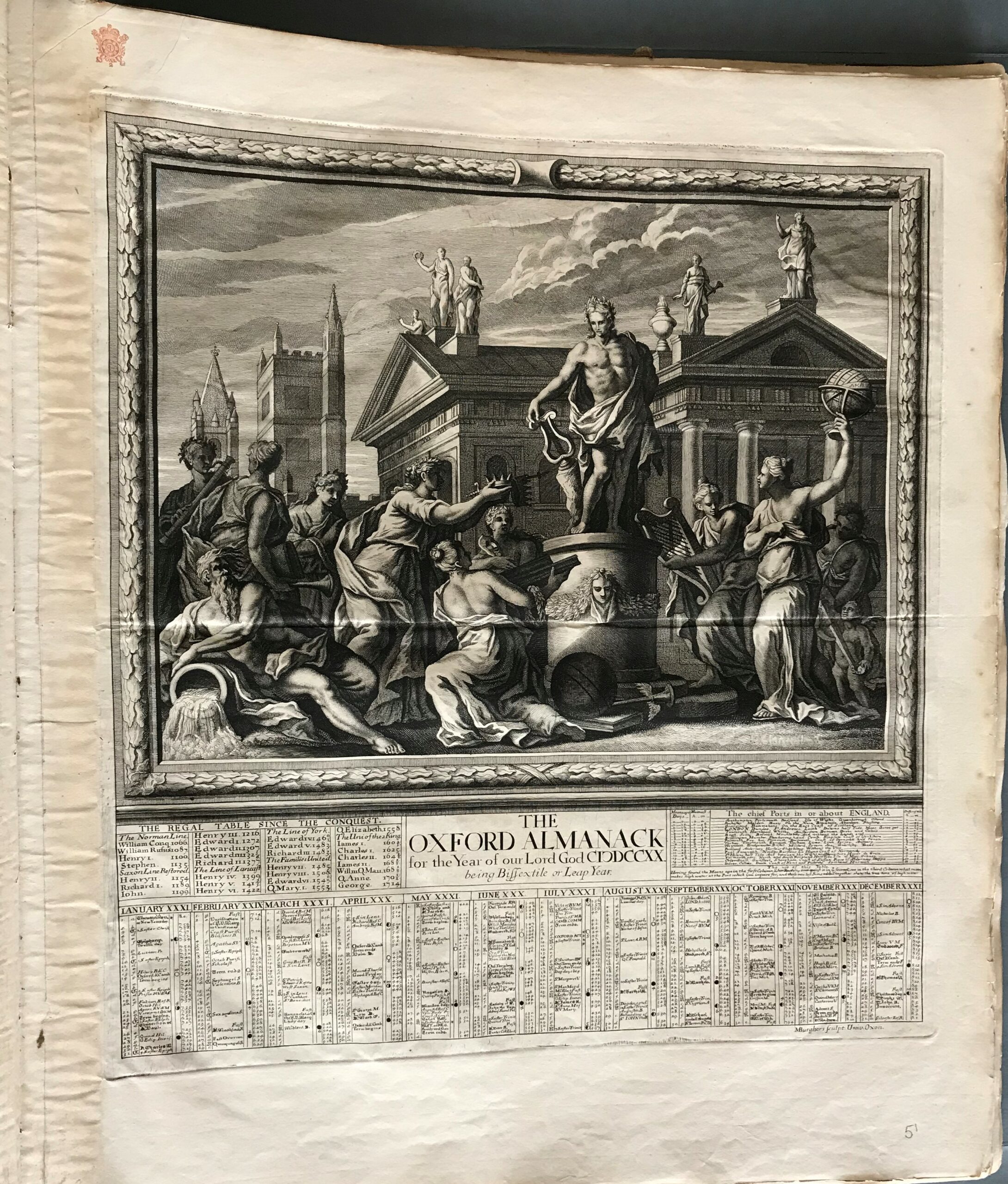

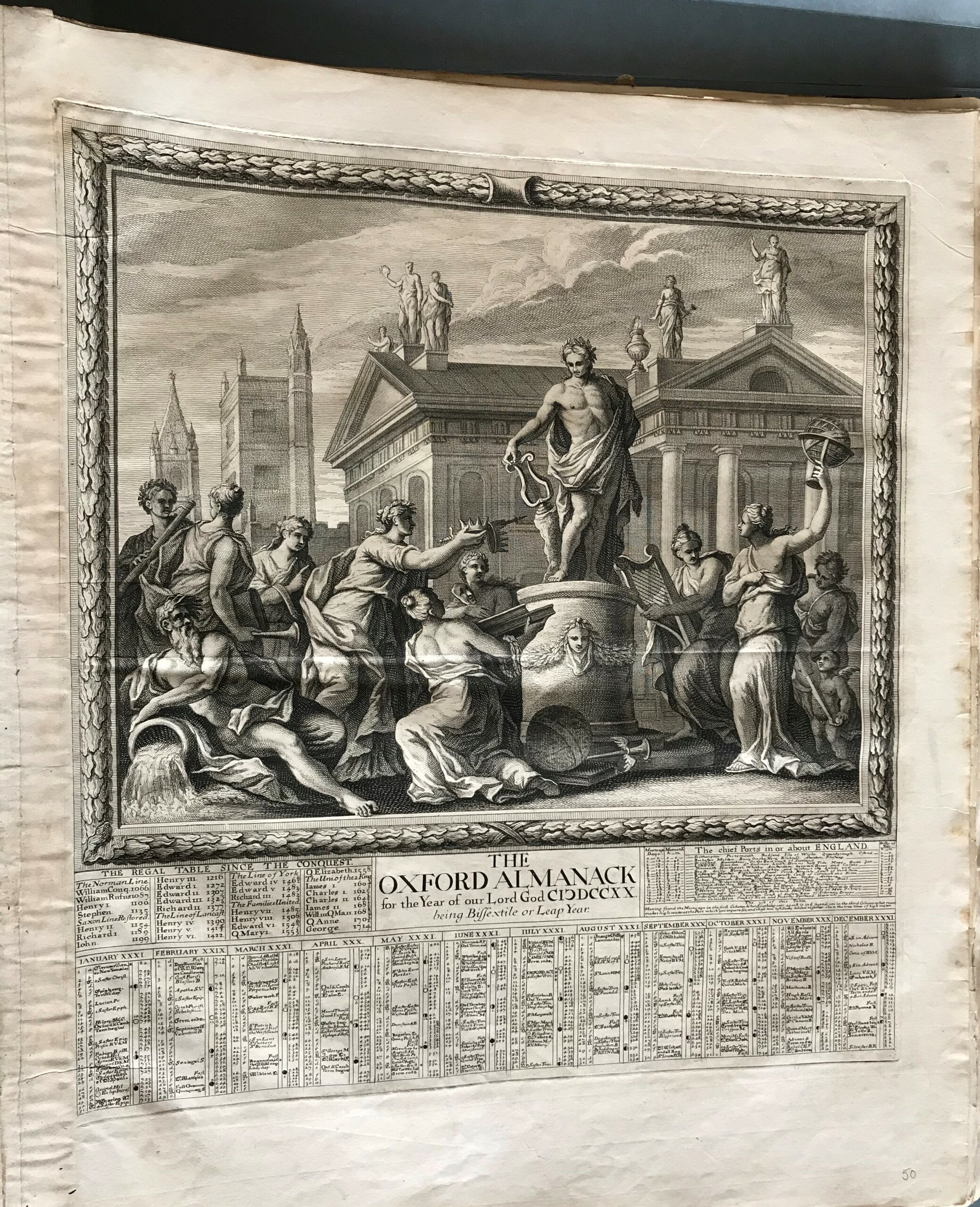

Thornhill’s drawing, in ink and grey and brown wash with white highlights, measuring 366 x 447 mm, shows Apollo on a plinth surrounded by the Muses, with the Clarendon Building on Oxford’s Broad Street in the background. Iconographically, this arrangement reflects two types of Oxford Almanack design: the allegorical subjects of the earliest almanacs and the architectural studies which began to feature in the 18th century. The Clarendon building, which stands in the background of this image, was designed by Hawksmoor and completed in 1713; Thornhill, though, was responsible for the figures of the Muses added to its roof in 1717 – for which drawings exist in Worcester College Library. There is a clear link between his architectural additions and this image.

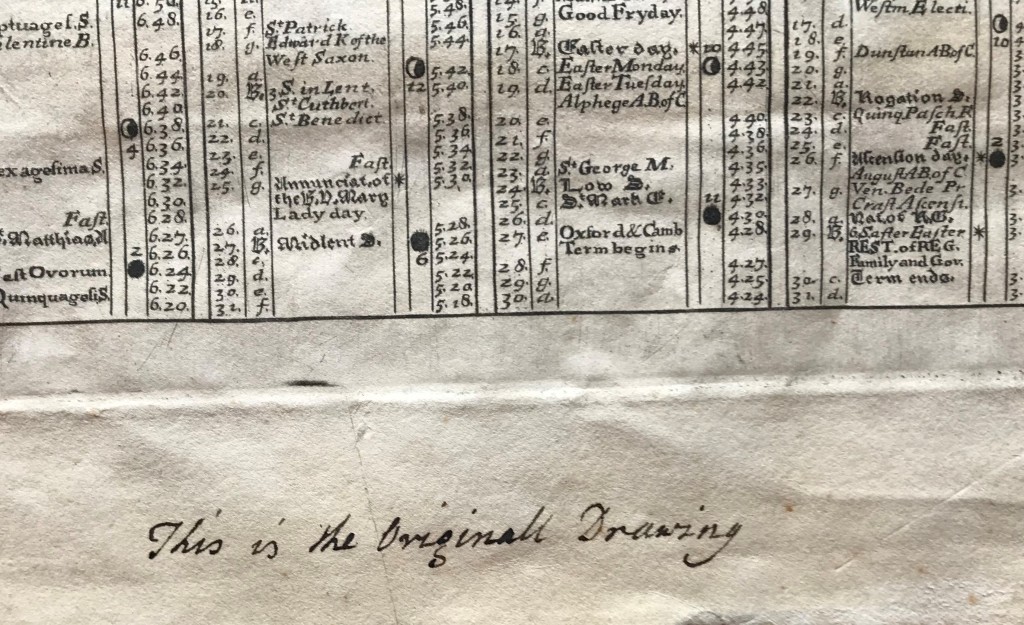

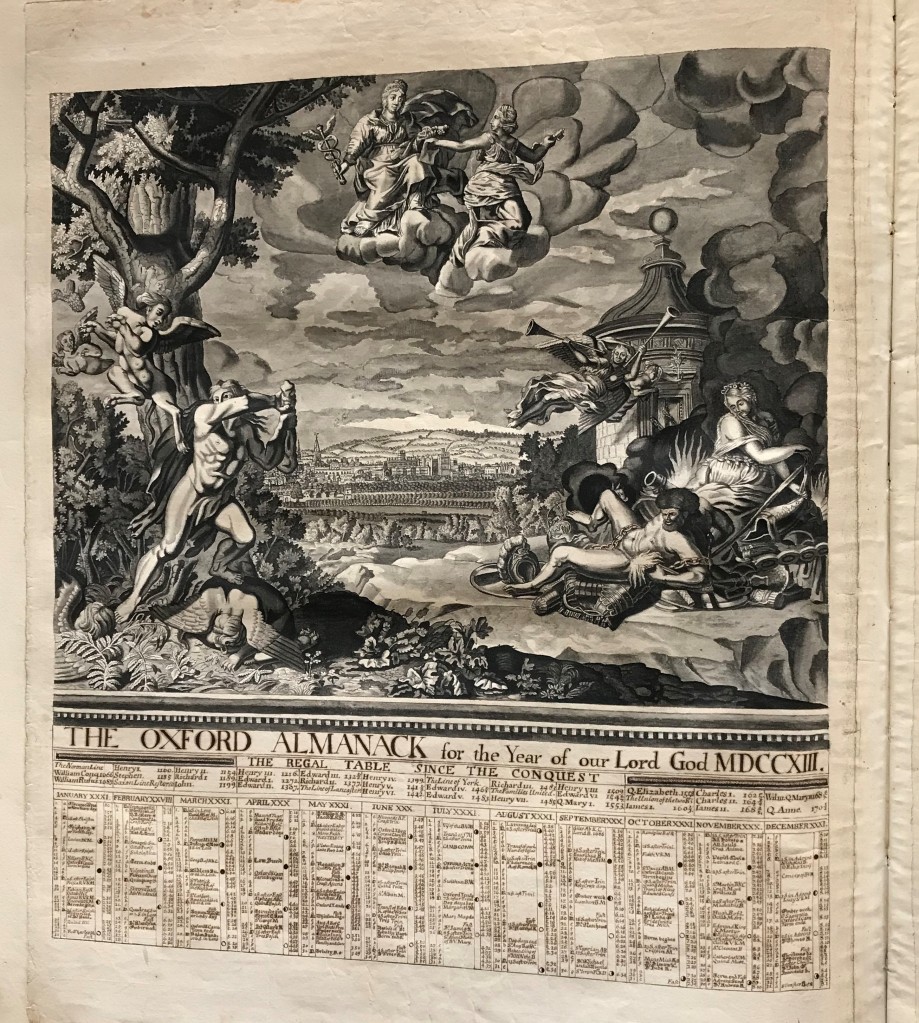

Launched in 1674 and with a new design produced for every year since 1676 (note that there was no almanac for 1675), the Oxford Almanacks are the longest running almanac series. Almanacs have a long history and were originally intended to serve as annual tables, with calendars, astronomical and ecclesiastical information. In 1674 Oxford produced its first almanac, perhaps to advertise the quality of the rising Oxford University Press (see Petter, Oxford Almanacks, page 3). Oxford Almanacks quickly developed to combine an image in the upper part of the sheet, with a calendar and informational tables in the lower (the Almanack of 1678 adopted this arrangement). The 1720 almanac includes a calendar for that year (with, for example, the days of University terms marked),a Regal Table (showing the dates of English monarchs from the Norman Conquest), and a table of ‘The Chief Ports in or about England’, together with their high tide calculations. Thornhill’s drawing has the engraved and printed calendar and tables stuck into this space to give a sense of what the finished product would look like. Informational as these features are, the unique feature of the Oxford Almanacks is the large portion of the sheet taken up by a picture.

The ‘brainchild’ of Dr John Fell (1625-1686), Dean of Christ Church and one of the first Delegates for Printing appointed by the University, responsibility for the Almanacks seems to have fallen on Henry Aldrich (1648-1710), who would also become Dean of Christ Church in 1689, and who from 1676 supervised their printing and design. Aldrich was a friend of Dr George Clarke, the benefactor of Worcester College and designer of its Library, and on Aldrich’s death, Clarke also became involved in the production of the almanacs (Petter, Oxford Almanacks, page 9). Correspondence in the Bodleian shows that it was Clarke who persuaded Sir James Thornhill (1675/6-1734), in the 1710s perhaps England’s leading baroque painter, to design 1720’s Almanack (see Bodl. MS. Ballard xi, f. 122; xx, f.107, quoted in Petters, Oxford Almanacks, page 11). Certainly, it was through Clarke that the drawing came to Worcester, and it is Clarke’s handwriting at the bottom of our sheet which notes ’This is the Originall Drawing’.

Clarke also collected printed versions of the Almanacks and his collection (left to Worcester College) includes both engravings of the 1720 print: that printed from the plate by Michael Burghers (shown here on the left, with a red duty stamp in the top left corner), and that by Claude du Bosc (shown here on the right).

In the early 18th century, when about 9,000 copies of each almanac were printed (see Petter, Oxford Almanacks, pages 21-22), two plates were needed for practical reasons as the plates would become worn through the printing process. The work of two engravers on the 1720 image reflects, however, Thornhill’s concern with the quality of the engraving. By 1720 Burghers, Engraver to the University since 1692, had been engraving the Almanacks since 1676 (History of Oxford University Press, volume 1, page 526) and it appears that Thornhill ‘considered him a ‘bad graver’ who could not do justice to his drawing’ (Petter, Oxford Almanacks,page 11). Claude Du Bosc (1682-c.1746) had already engraved Thornhill’s work and, although unsigned, the second plate is probably by him (see Petter, Oxford Almanacks, page 52).

These two copies of the finished 1720 print are from the collection left by George Clarke to Worcester College Library on his death in 1736. His set is complete for the years 1674-1736, and indeed the run was continued uninterrupted until 1776; there is then a gap until 1835, after which point we again have a fairly full run until 1977, although with more gaps than in earlier years. Interestingly, in Clarke’s own collection are two further drawings for Almanacks: one for 1688, and one for 1713. Clarke’s ownership of these drawings is further proof for his involvement in the Almanack endeavour, although Thornhill’s drawing for 1720, with its architectural interest, perhaps most closely illustrates Clarke’s influence.

Mark Bainbridge, Librarian

Bibliography

- Petter, H.M., The Oxford Almanacks (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1974)

- Eliot, S. (ed), The history of Oxford University Press (Oxford: OUP, 2013-2017)