The trouble with attribution

24th March 2017

The trouble with attribution

Following on from last month’s blog post (on Inigo Jones’ designs for Somerset House), there are two further sheets of drawings linked to Somerset House by the architectural historians John Harris and A.A. Tait in their 1979 catalogue: H&T 15 and 249 (which are joined together on one sheet) and H&T 16 (an 18th-century copy of the earlier sheet; references are to Harris and Tait, Catalogue of the drawings by Inigo Jones, John Webb, and Isaac de Caus at Worcester College Oxford, abbreviated as H&T). We rather ran out of space last month to include them with the designs for Somerset House’s Strand front, but further reading has shown that a separate blog post is indeed more suitable: these drawings have a complicated history that reminds us of the skill needed to read and interpret such objects.

H&T 15/249

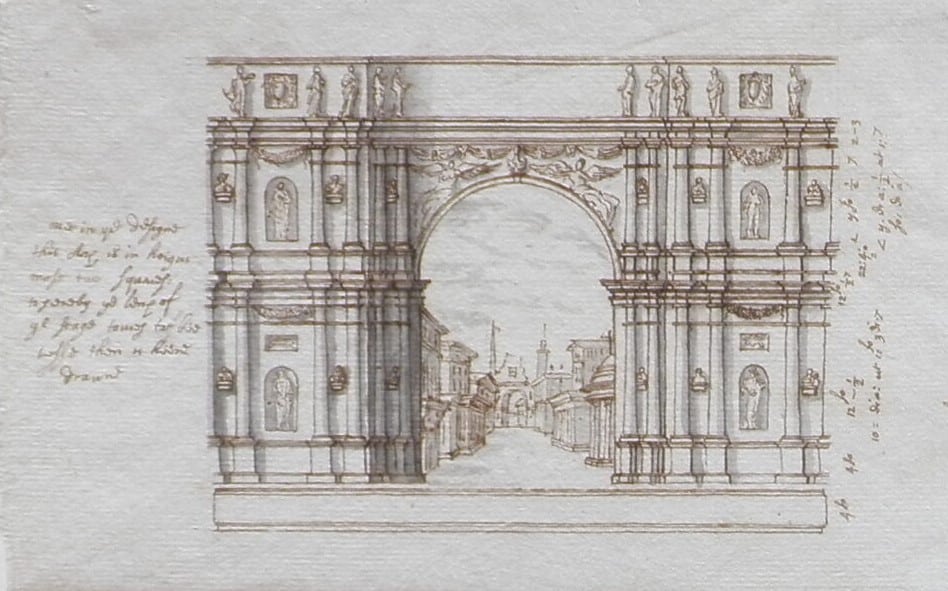

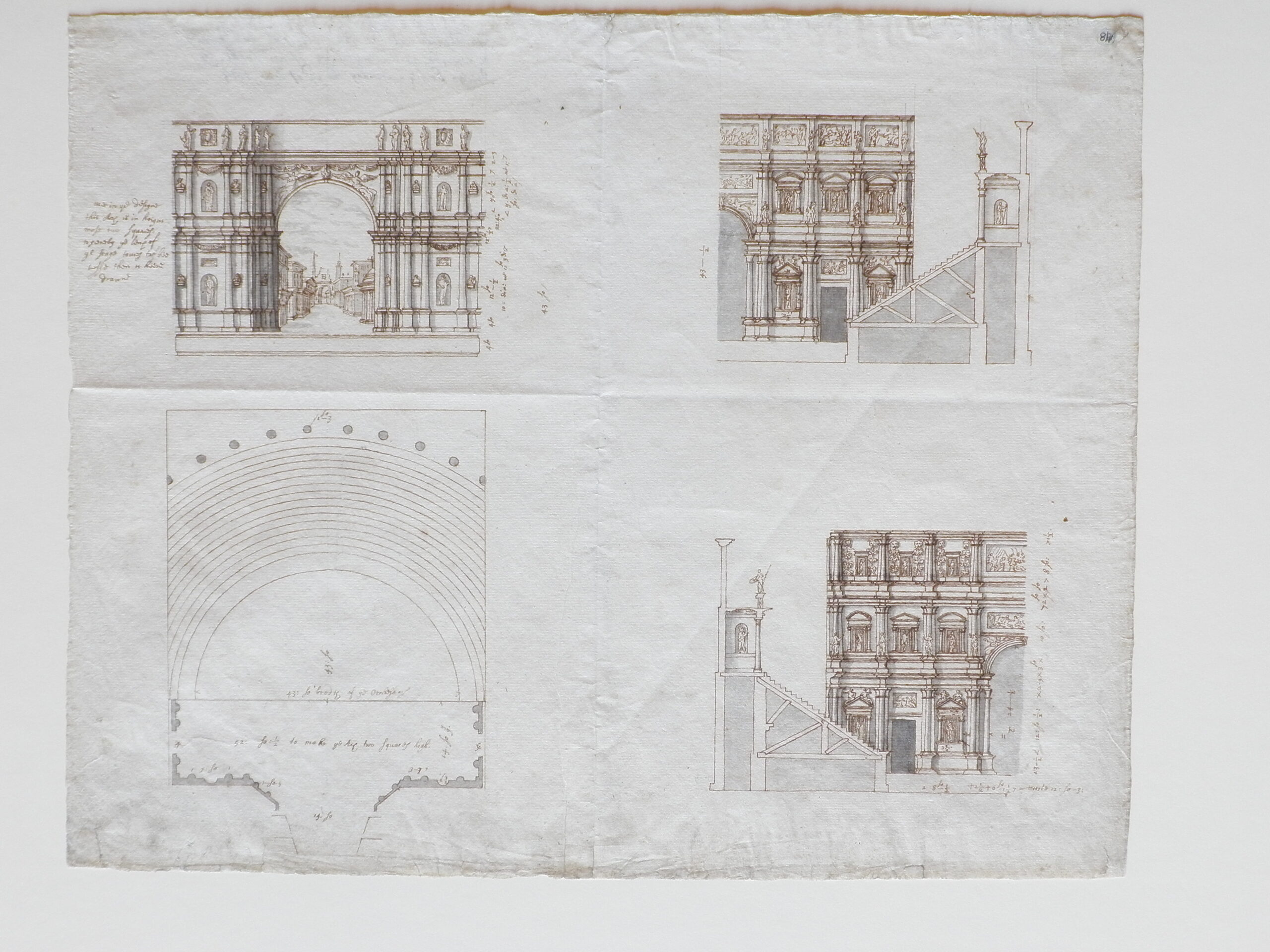

H&T 15 and 249 is now one sheet (with a clear join down the middle – the two sheets were joined early, perhaps in the 17th century, and certainly by the early 18th), 300 x 390 mm, in pen and ink: on the left-hand side of the page is a design for the elevation and plan of a scenic theatre; on the right-hand side, two half sections of a theatre identified as the Teatro Olimpico in Vicenza. When this image was first published by W. Grant Keith in 1917, Grant Keith saw the similarity between the theatre designs on the right and a drawing by the Italian architect Andrea Palladio for the Teatro Olimpico – a drawing that was once owned by Inigo Jones (the Palladio drawing is now in the RIBA Drawings Collection: B.D. XIII/5; Lewis, Catalogue, no. 124). It was perhaps this link that led Grant Keith so securely to suggest Jones as the designer and draughtsman of this image.

Jones was certainly interested in Palladio’s Teatro Olimpico at Vicenza. In a 17th-century hand resembling John Webb’s (see Orrell, The theatres of Inigo Jones and John Webb, page 161) on the verso of our drawing is the statement: ‘The Theatre at Vicenza – designed by Palladio and described by Inigo Jones at ye beginning of Palladio’ – that is, Jones made notes on the Teatro Olimpico in his own heavily annotated copy of Palladio’s published treatise on architecture, the Quattro Libri.

17th-century notes on the verso of H&T 15/249.

Indeed, turning to the volume of Palladio owned by Jones (also in the Worcester collections), one can find Jones’ very comments inscribed on the verso of the fifth fly-leaf (facing the volume’s title page):

Jones commented upon the perspectives visible through the arches in the scaenae frons (i.e. the scenic architectural background) of the Teatro Olimpico (a project begun by Palladio in the last year of his life, 1580, and completed by Scamozzi in 1584), it being the theatre’s ‘chief artifice… that whear so euer you satt you sawe on[e] of these Prospectes’ (Jones’ fly-leaf annotations). A similar artifice is used in the main arch in the top-left of H&T 15/249. Yet this link between Jones and Palladio’s Teatro Olimpico, made so early after the drawing’s discovery, has perhaps clouded the attribution of this drawing in Worcester’s collection.

The most recent discussion of the drawing, by John Orrell, notes: ‘It seems more likely… that the whole set has nothing to do with Jones at all’ (Orrell, The theatres of Inigo Jones and John Webb, page 161). Accepting a fact noted by Harris and Tait in their catalogue, namely that the drawing is actually in the hand of Jones’ apprentice, John Webb (who is known to have made copies of designs by Jones as a record for posterity, perhaps intending to publish them as a treatise on Jonesian architecture), Orrell feels that this drawing represents ‘John Webb’s scheme for an apparently unrealized scenic theatre based on Palladio’s Teatro Olimpico’ (The theatres of Inigo Jones and John Webb, page 160). Remarking on the notes in Webb’s handwriting on the practicalities of the design (on the left-hand sheet, to the left of the elevation and across the stage in the plan), Orrell thinks this is more likely to have been a work-in-progress, representing Webb’s own experimentation with theatre designs after Palladio’s Teatro Olimpico, rather than a Webb copy of a Jones design.

If this is not already a little complicated, things can become a bit more confusing. The drawing Grant Keith published and discussed in 1917 was not actually drawn by Webb: rather it was an almost exact copy of Webb’s drawing (still unknown to Grant Keith in 1917) made by George Clarke’s friend and collaborator, Henry Aldrich (1648-1710), Dean of Christ Church, Oxford. That Aldrich or Clarke connected the design with Jones is suggested by the fact that Aldrich’s drawing (H&T 16) was stored between folios 56 and 57 of Jones’ own copy of Palladio (i.e. between pages 34 and 35 of Book II of the Quattro Libri – pages which have, it must be noted, no link to the Teatro Olimpico, although that project, Palladio’s last, is not included anywhere in the Quattro Libri, having only been begun in 1580): H&T 16 (Aldrich’s drawing) was folded and trimmed so as to fit the book.

H&T 16

So, in summary, what we have here are two drawings (presented under three catalogue headings):

- H&T 15 and 249: seventeenth-century drawings in the hand of John Webb, originally thought to be by Jones and to relate to designs for an indoor theatre for the Stuart court, but now considered to represent theoretical designs by John Webb himself, tied to no identifiable theatre project.

- And H&T 16: an 18th-century copy of H&T 15 and 249 by Henry Aldrich.

Although very close copies (Aldrich has even paraphrased Webb’s notes in a similar position on the verso), there are nevertheless differences: Webb, the draughtsman of H&T 15/249, has used cross-hatching as opposed to Aldrich’s ink wash; in H&T 15/249 you can see the scoring which was used to guide Webb’s pen. Aldrich’s copy, most likely made for his own architectural education, dispensed with the need for scored lines; it nonetheless illustrates the use made of Clarke’s drawing collection by his architecturally-minded friends in their own studies.

Before leaving these drawings, a word is perhaps needed on the link with Somerset House. The connection with Somerset House was made as Inigo Jones was known to have been commissioned many times to stage performances there and H&T 15/249, if related to a real theatre, seems to have been for an indoor one: the design has no entrance or exit for spectators, which led Per Palme to suggest that the ‘design was for a temporary structure in an existing room’ (H&T, page 15). When the drawing’s link to Jones was weakened, however, the link with Somerset House evaporated. We see in H&T 15/249 rather Webb’s own theoretical work on theatre design, undoubtedly influenced by Jones’ notes on the Teatro Olimpico at Vicenza and, indeed, Jones’ earlier theatres – as Orrell has noted, Jones completely changed English stage design (Orrell, page 3). And just as Webb learned from Jones, in the 18th-century copy of H&T 15/249 (that is in H&T 16), we see Henry Aldrich learning from Webb, copying his design as a means of architectural education.

Mark Bainbridge, Librarian

Bibliography

- Harris, J. and A.A. Tait, Catalogue of the drawings by Inigo Jones, John Webb, and Isaac de Caus at Worcester College Oxford (Oxford, 1979)

- Lewis, D., The drawings of Andrea Palladio, second edition (New Orleans, 2000)

- Grant Keith, W., ‘A theatre project by Inigo Jones’, Burlington Magazine xxxi (1917), pages 61-70

- Orrell, J., The theatres of Inigo Jones and John Webb (Cambridge, 1985)