History of Science books from Worcester’s collections

29th November 2019

History of Science books from Worcester’s collections

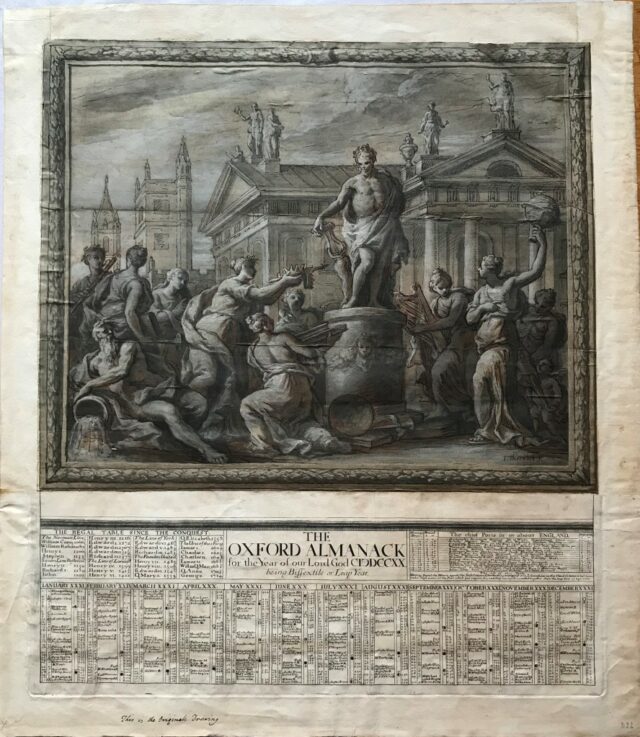

Last month the Library was one of 12 college libraries taking part as points on a college walking trail exploring ‘History of Science Collections in Oxford Colleges’ (see Thinking 3D: history of science collections in Oxford colleges). 68 visitors came in 2 ½ hours to look at five books on the history of science from the College’s collections. In this month’s blog, we seek to replicate the exhibition online.

Moving from the scientific renaissance of Italy to the scientific revolution of 17th– and 18th-century England, the books show how science and printing are deeply intertwined. Combinations of text and images in the following books allowed information and knowledge to be transmitted more easily.

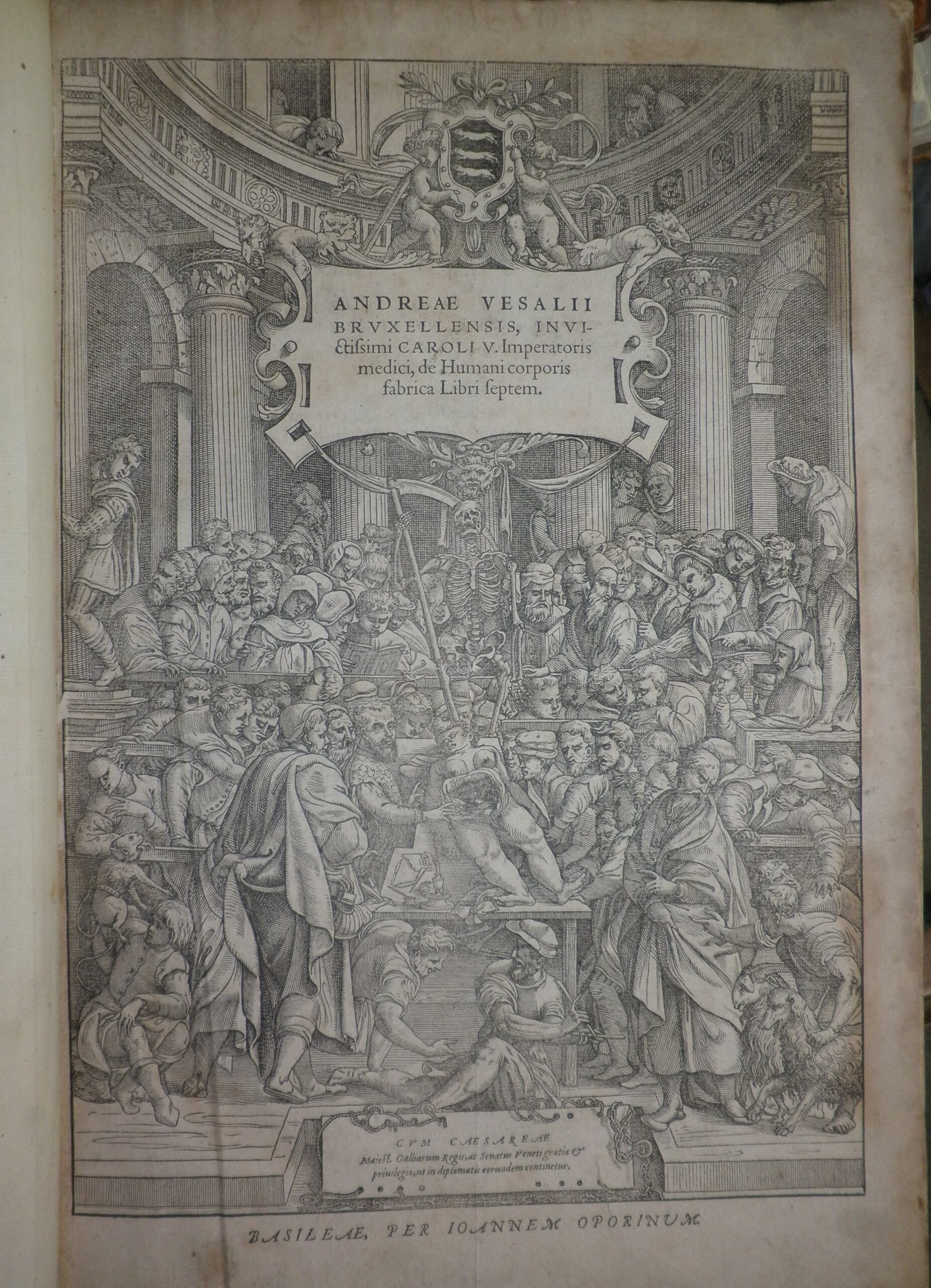

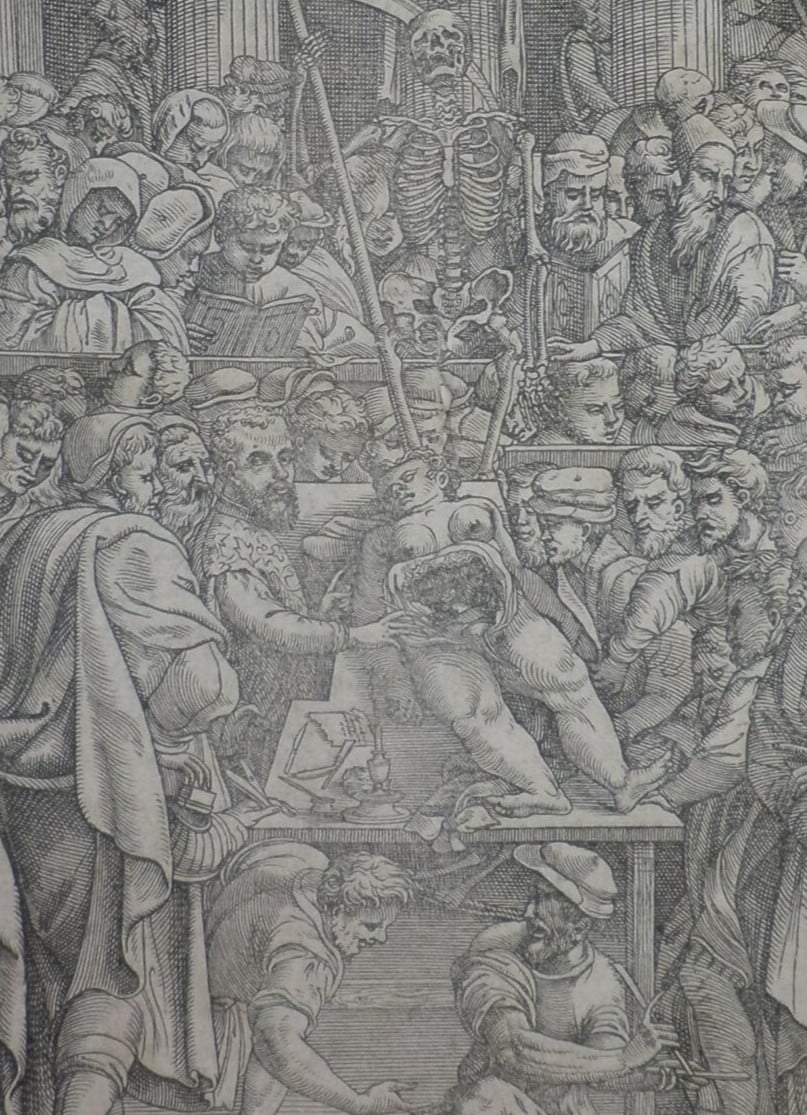

To illustrate the early history of science, the College is fortunate to own a copy of Vesalius’ De corporis humani fabrica (Basle, 1555). Vesalius was the creator of modern anatomy and his book has been described as the first great modern work of science. The magnificent plates by Jan van Calcar illustrate the union of science and art in the Renaissance. Worcester owns the second edition; the first appeared in 1543.

Illustrated with c. 200 woodblock prints, the book’s most famous images are perhaps those of the 14 ‘muscle-men’ at the beginning of Book II. As the pages progress, so does the state of dissection. If all 14 plates were joined together, the backgrounds would form a panorama of the Euganean Hills near Padua, where Vesalius studied and wrote his magnum opus.

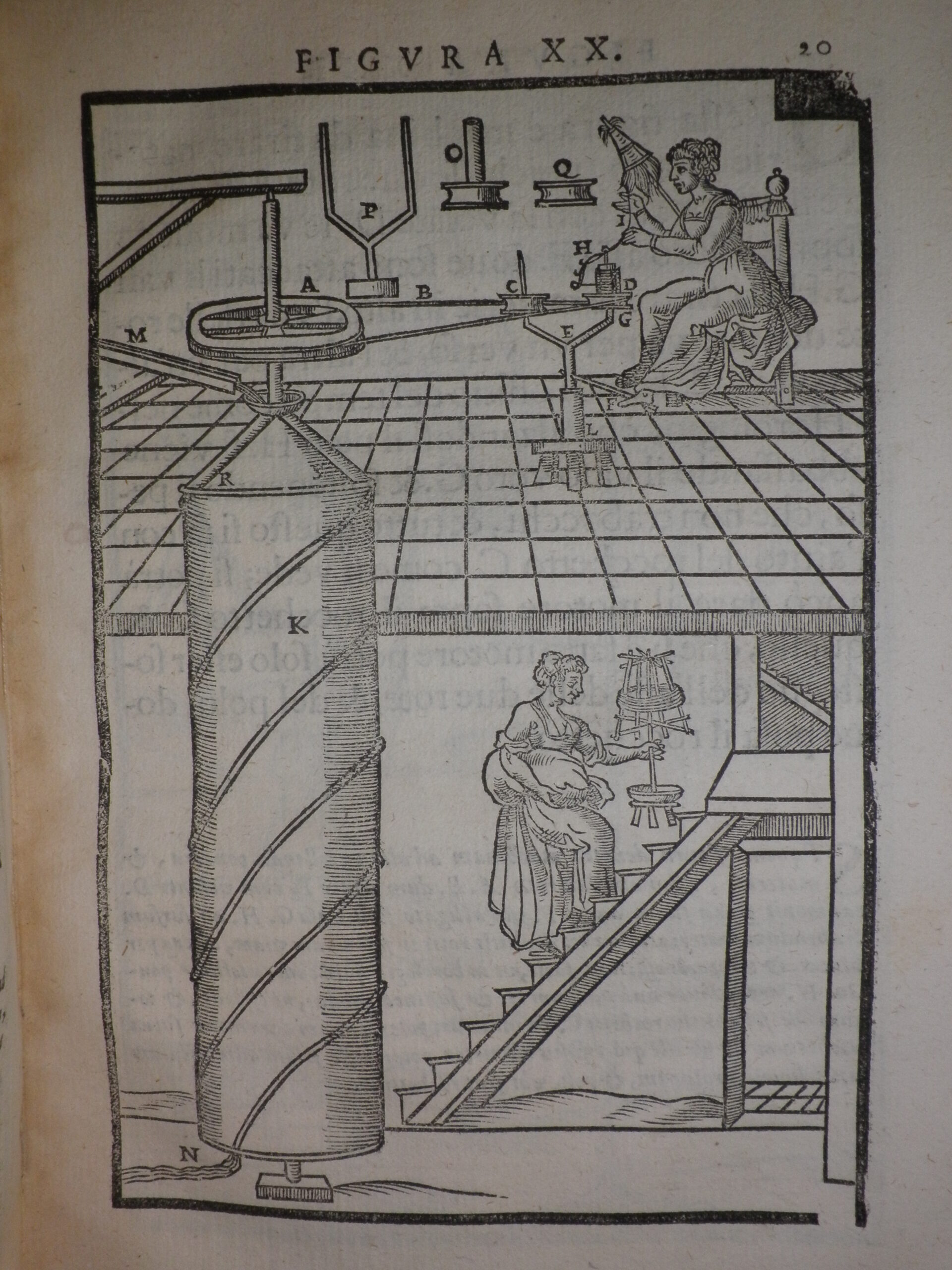

From a work on the human body we move to a treatise on machines: the much lesser-known Giovanni Branca’s Le machine. Published in Rome in 1629, this treatise reflects a time and place, seventeenth-century Italy, where the invention of machinery was very actively pursued. Branca’s small octavo volume contains engravings with descriptions in Italian and Latin. Figure 20 illustrates a hydraulic spinning-machine.

Although symbolic of 17th-cenutry Italy’s ‘theatres of the machines’ (see Keller, ‘Renaissance theaters of machines’), it must be noted that Branca did not claim to be the creator of all the machines illustrated; in one instance he is unclear how the machine works.

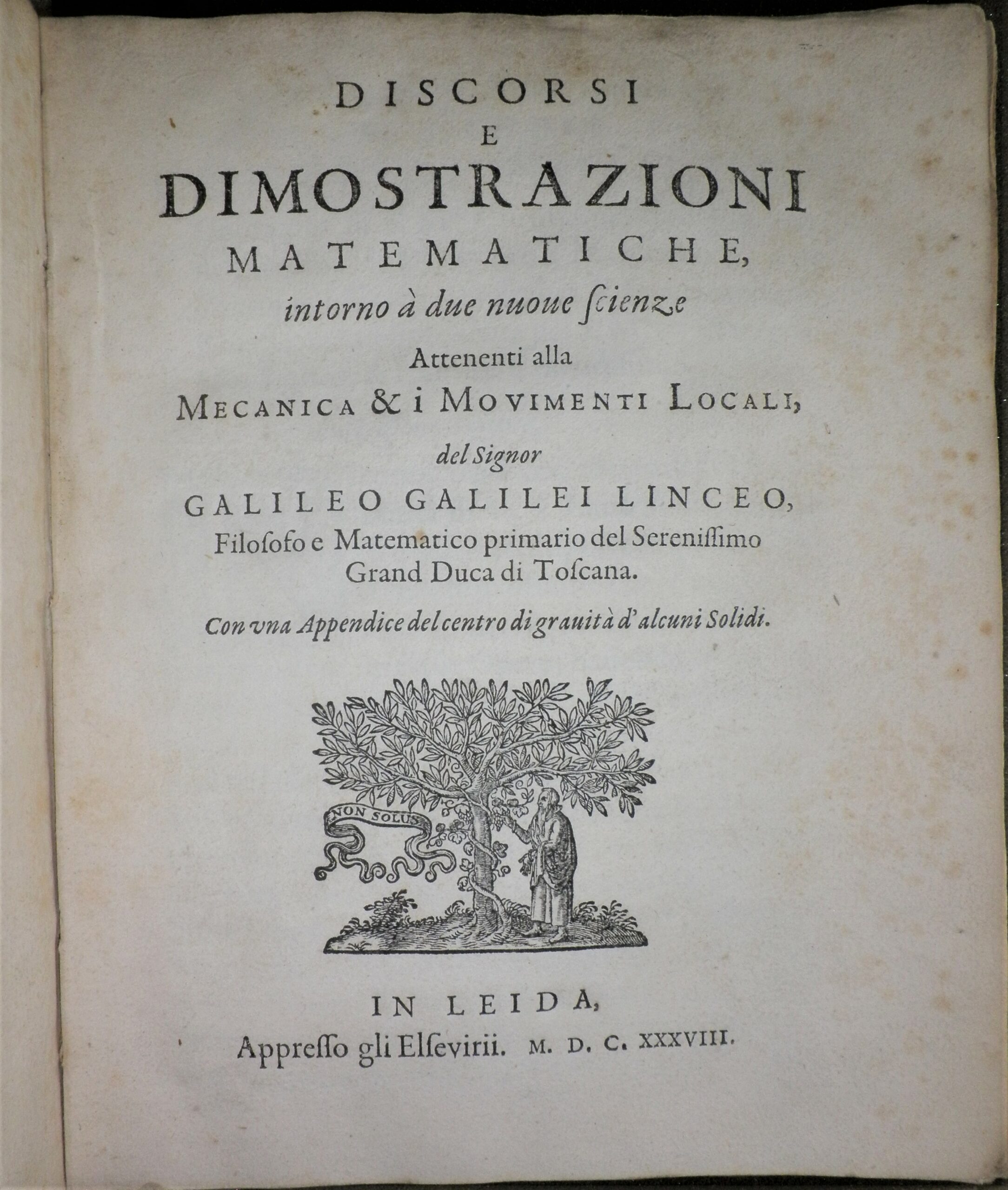

From the relatively unknown Branca we move to the man called by Einstein ‘the father of modern physics – indeed of modern science’: Galileo Galilei. His final book, Discorsi e dimostrazioni matematiche, intorno due nuove scienze attenenti alla mecanica & i movimenti locali (Leiden: Elzevier Press, 1638) is commonly called in English The Two New Sciences. A work on mechanics and moving bodies, it was written during Galileo’s house arrest, ‘bringing to fruition a body of influential work that had begun in the 1590s’ (Dear, Revolutionizing, page 108). Galileo was forbidden to publish the text in Italy by the Congregation of the Index (i.e. the Index of Prohibited Books), but managed to have a manuscript copy smuggled to the Elzeviers in Holland.

Such impediments to science mean that as we move into the second half of the seventeenth century, our books are no longer the products of Italian scientists, but are English publications. These are the products of post-Civil War England, ‘a stable society…, more or less democratic, increasingly prosperous, and tolerant, if not of all free-thinkers, at least of the kind of free-thinking involved in science’ (Gribbin, The Fellowship, page xiv).

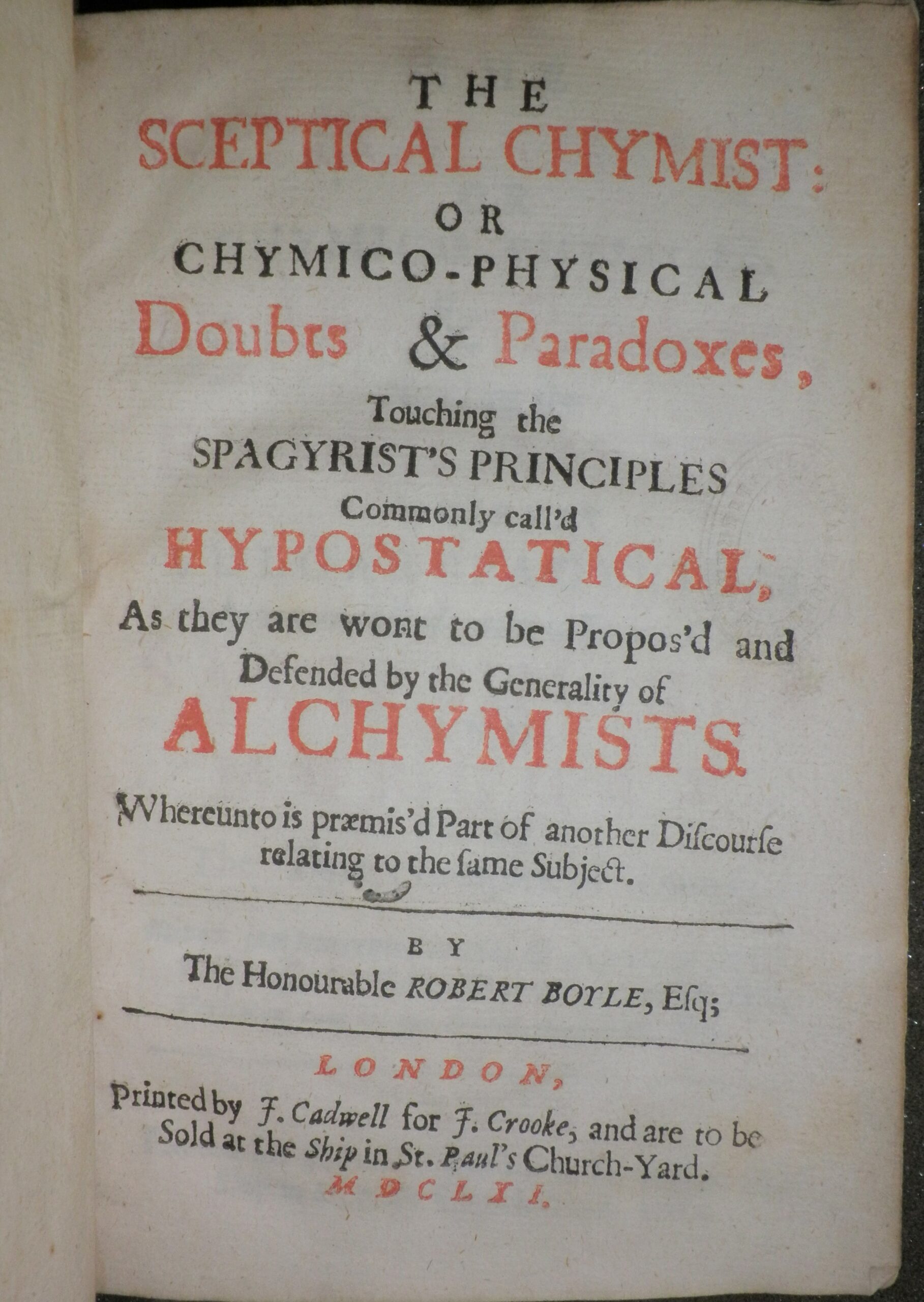

Robert Boyle (1627-1691), a founder member of the Royal Society (founded 1660), was one such free-thinker and from Worcester’s collections we present The sceptical chymist (London, 1661). Although some have called this book the work which created the science of modern chemistry, it is perhaps truer to say that it stands on the border between alchemy and chemistry.

Boyle had followed traditional alchemists’ pursuits such as the search for the Philosopher’s Stone, but used this dialogue to attack the classical doctrine of the four elements (earth, water, air and fire), also dismissing the Paracelsian view of three fundamental elements. In the sixth part, Boyle defined ‘chemical elements’ as ‘perfectly unmingled bodies’ – a statement approaching the modern concept. Boyle denied, however, that any known substance satisfied this definition, taking the view that all known materials were compounds.

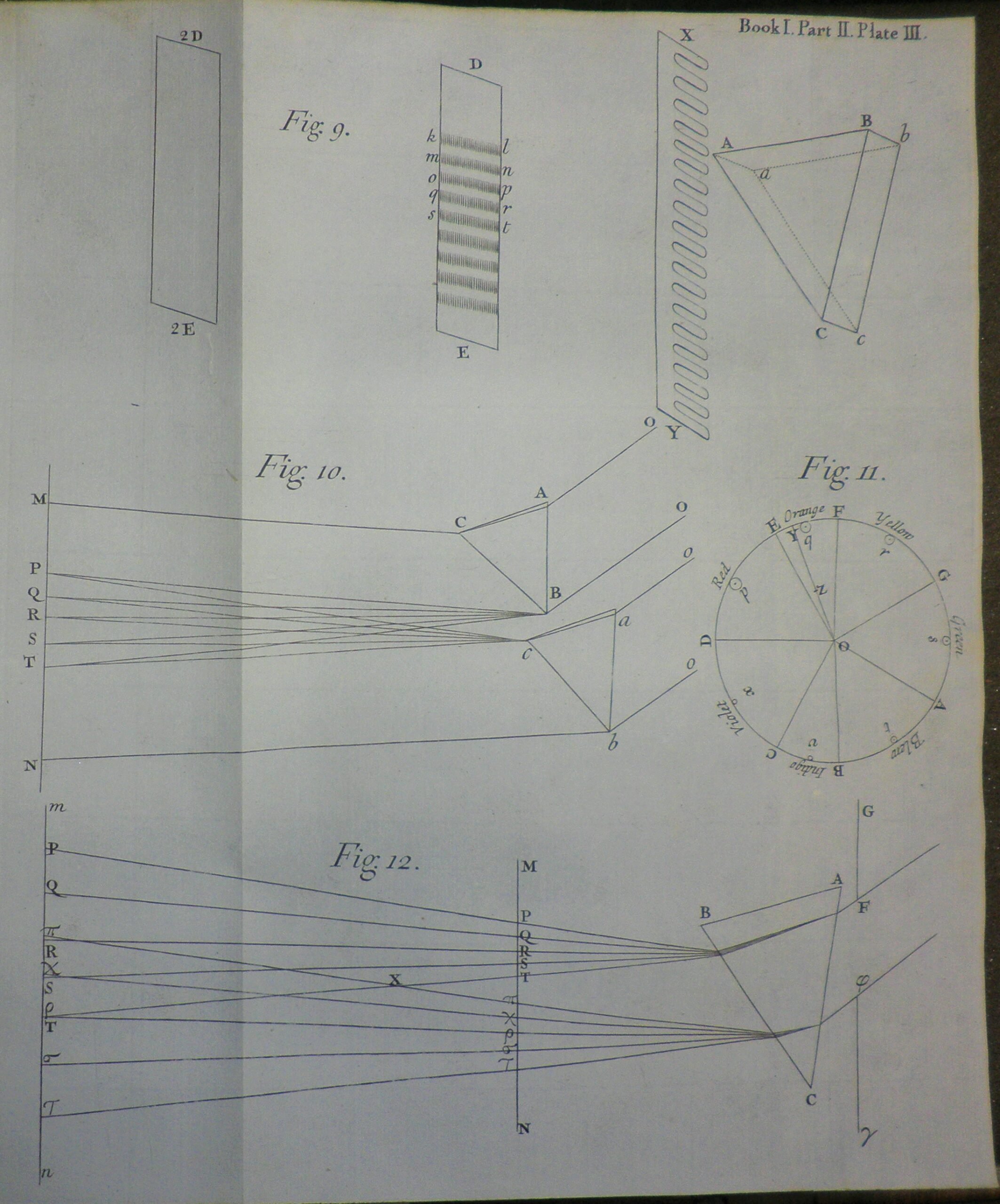

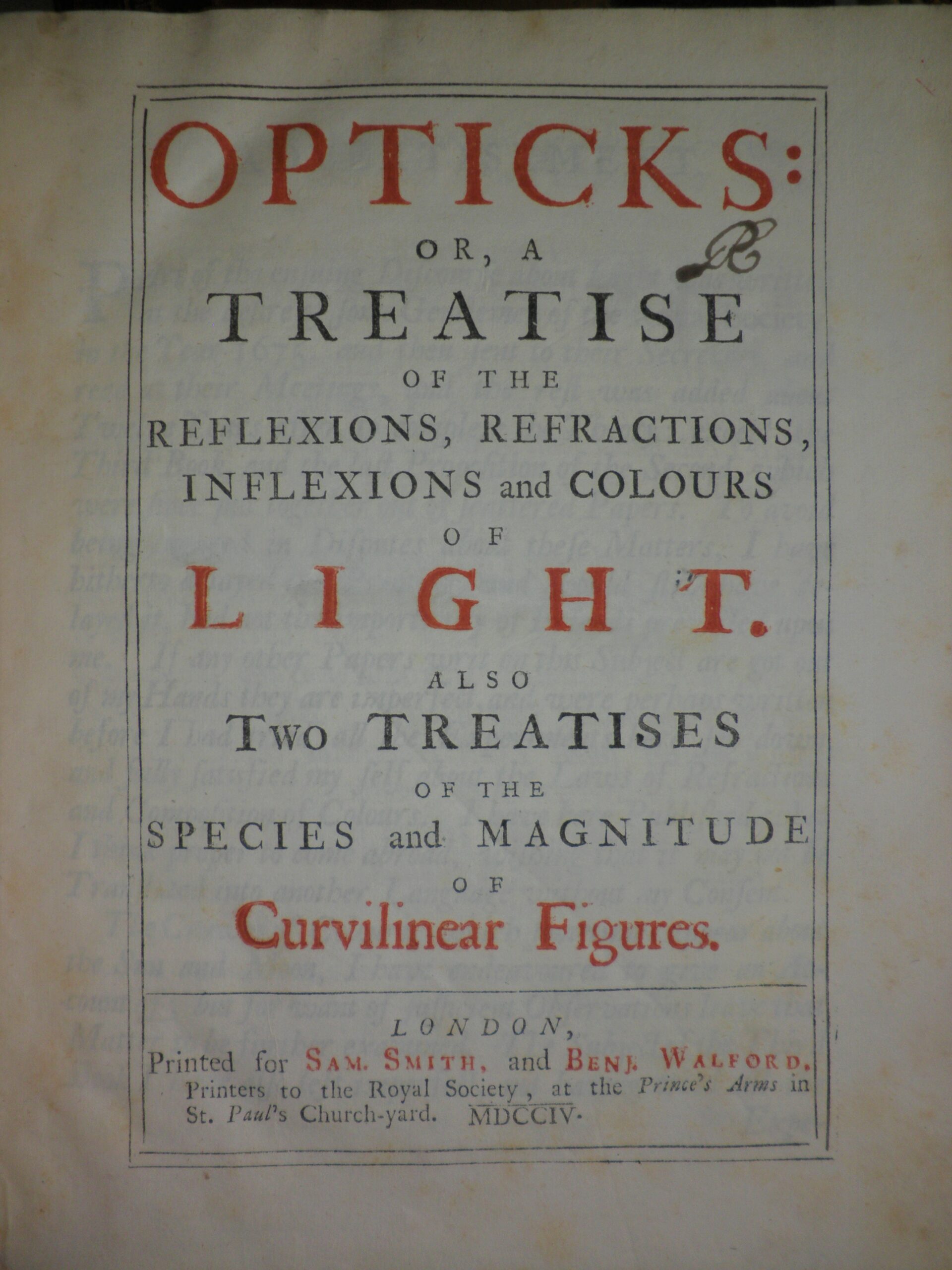

Boyle was an experimental scientist and it is with another famous ‘experimenter’ that we end: Isaac Newton (1642-1727). His Opticks (London, 1704), of which the Library owns a first edition, described Newton’s discoveries and theories concerning light and colour, based on experiments conducted in the later 1660s and early 1670s. Famously, the work documents his experiments passing light through a prism.

The volume ends with a section of ‘Queries’ which ‘helped to guide the experimental philosophy of the eighteenth century’ (Oxford Companion to the History of Modern Science, page 574).

All of these books were published before the foundation of Worcester College (in 1714) and certainly before science was a part of the College’s teaching. Indeed, although the College had Fellows with scientific interests in the 19th century – for example, William Odling, the Waynflete Professor of Chemistry (Fellow 1872-1912), and Andrew Bloxam (1801-1878), the naturalist on the Blonde’s voyage to Hawaii in 1824 – it was not until the mid-20th century that the sciences really became a part of College (see Parker, ‘Fellows and Tutors’, page 136). These items from Worcester’s old library, therefore, in part reflect the collections of earlier donors: both the Branca and Newton belonged to George Clarke (his customary monogram can be seen on the title page).

The Vesalius was a wonderful donation in 1924 from Lionel Muirhead in memory of Provost Daniel and his wife Emily.

Neither Daniel nor his wife were medics, but as printers themselves, they would surely have appreciated the volume of Vesalius, a book which so successfully used printed text and images to convey new knowledge.

Mark Bainbridge, Librarian

Bibliography

- Keller, A., “Renaissance theaters of machines”, Technology and culture 19:3 (July 1978), pages 495-508

- Dear, P., Revolutionizing the sciences: European knowledge and its ambitions, 1500-1700 (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2001)

- Gribbin, J., The fellowship: the story of a revolution (London: Allen Lane, 2005)

- Heilbron, J. L. (ed), The Oxford companion to the history of modern science (Oxford: OUP, 2003)

- Parker, J., “Fellows and tutors”, in J. Bate and J. Goodman (eds), Worcester: portrait of an Oxford college (London: Third Millennium, 2014), pages 124-137