The George Clarke Print Collection

31st January 2018

The George Clarke Print Collection

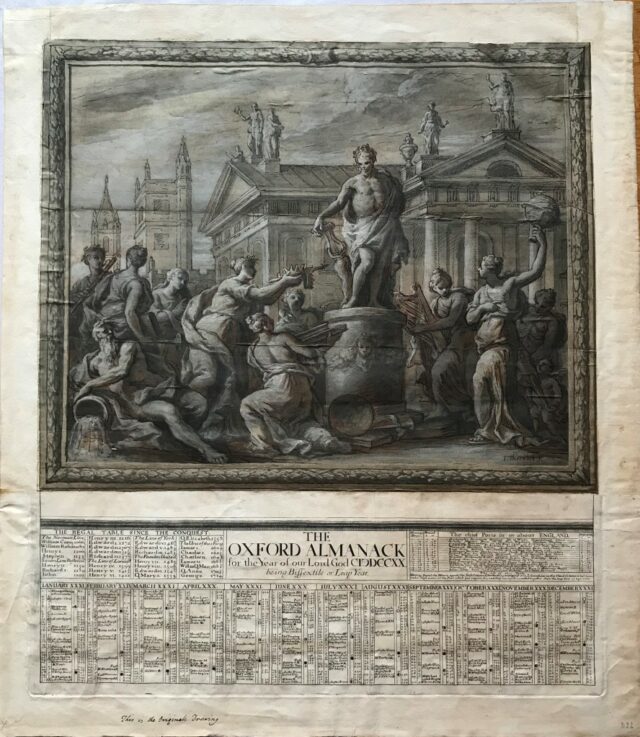

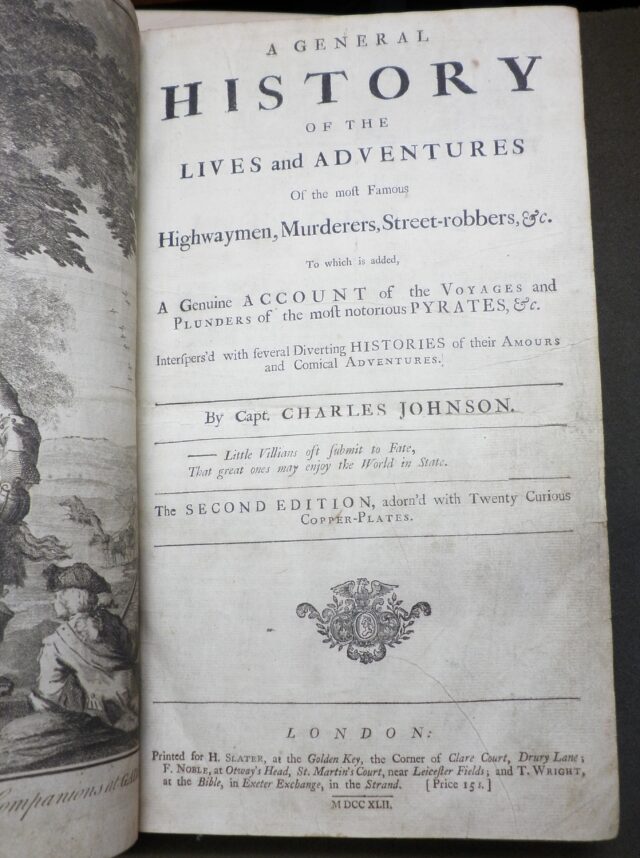

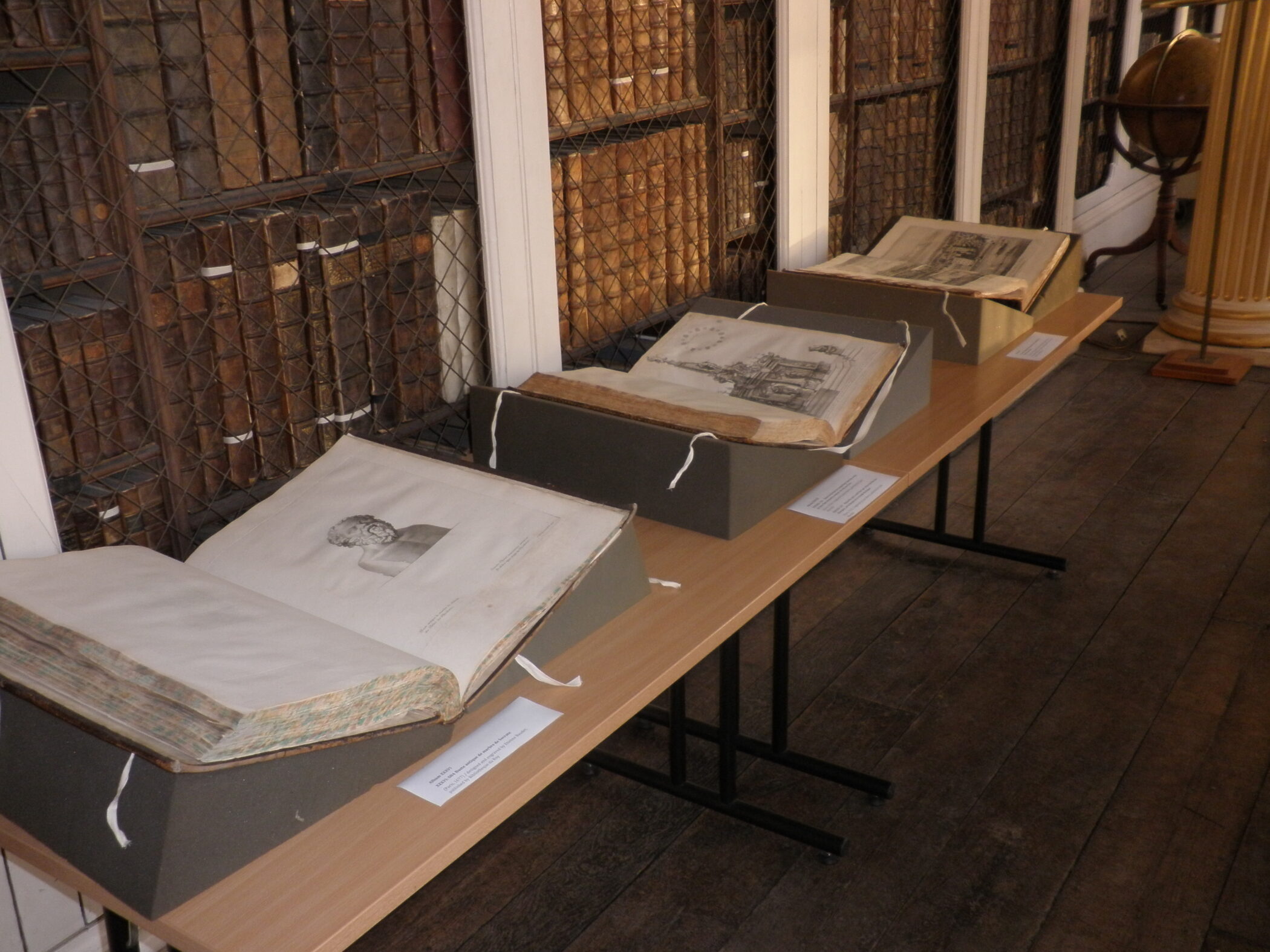

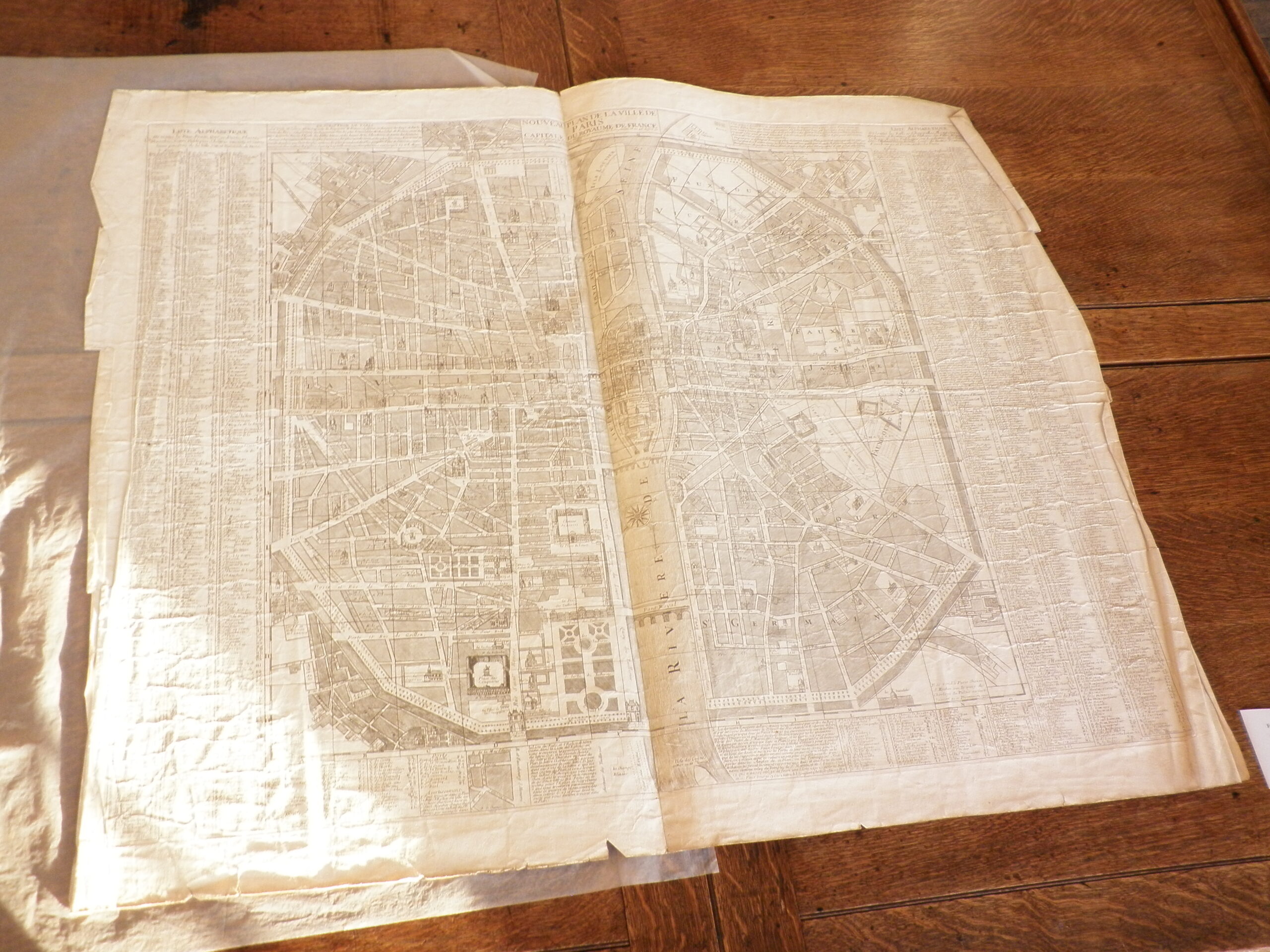

2018 began in Worcester College Library with a bit of post-Christmas exercise. It was the heavy-lifting of huge folio volumes containing hundreds of prints, together with the manoeuvring of large single sheets like the 1700 print of the Nouveau Plan de la Ville de Paris Capitale du Royaume de France, which measures 796 x 1000 mm. All are part of the George Clarke Print Collection: around 8,000 prints, in 76 bound volumes, together with c. 600 unbound items.

Nouveau Plan de la Ville de Paris Capitale du Royaume de France (Paris, 1700) / published by Claude Rocher

This is not a newly discovered collection: Timothy Clayton’s 1992 article provides a comprehensive introduction, and the whole was catalogued in the late 1990s by Clayton and Benjamin Thomas (see http://prints.worc.ox.ac.uk/). It is good, however, to see continued interest in what is a very rich and important resource. George Clarke’s collection is still complete, preserved in the contemporary albums and arranged as Clarke intended. As Professor Mark Ledbury (Power Professor of Art History and Visual Culture, and Director of the Power Institute, University of Sydney), who led the visit by delegates from the British Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies annual conference which occasioned the Library’s display of these prints, says:

“The collection, [although] less well known than other collections in the UK, notably the Pepys collection, … in some ways is fresher and richer – both in its completeness but also for what it might tell us about how ‘Tory taste’ needs nuancing – Clarke was in dialogue with contemporary artists in Britain and France, and combined his ‘blue chip’ collecting with more adventurous forays into contemporary art.”

George Clarke / Circle of Godfrey Kneller

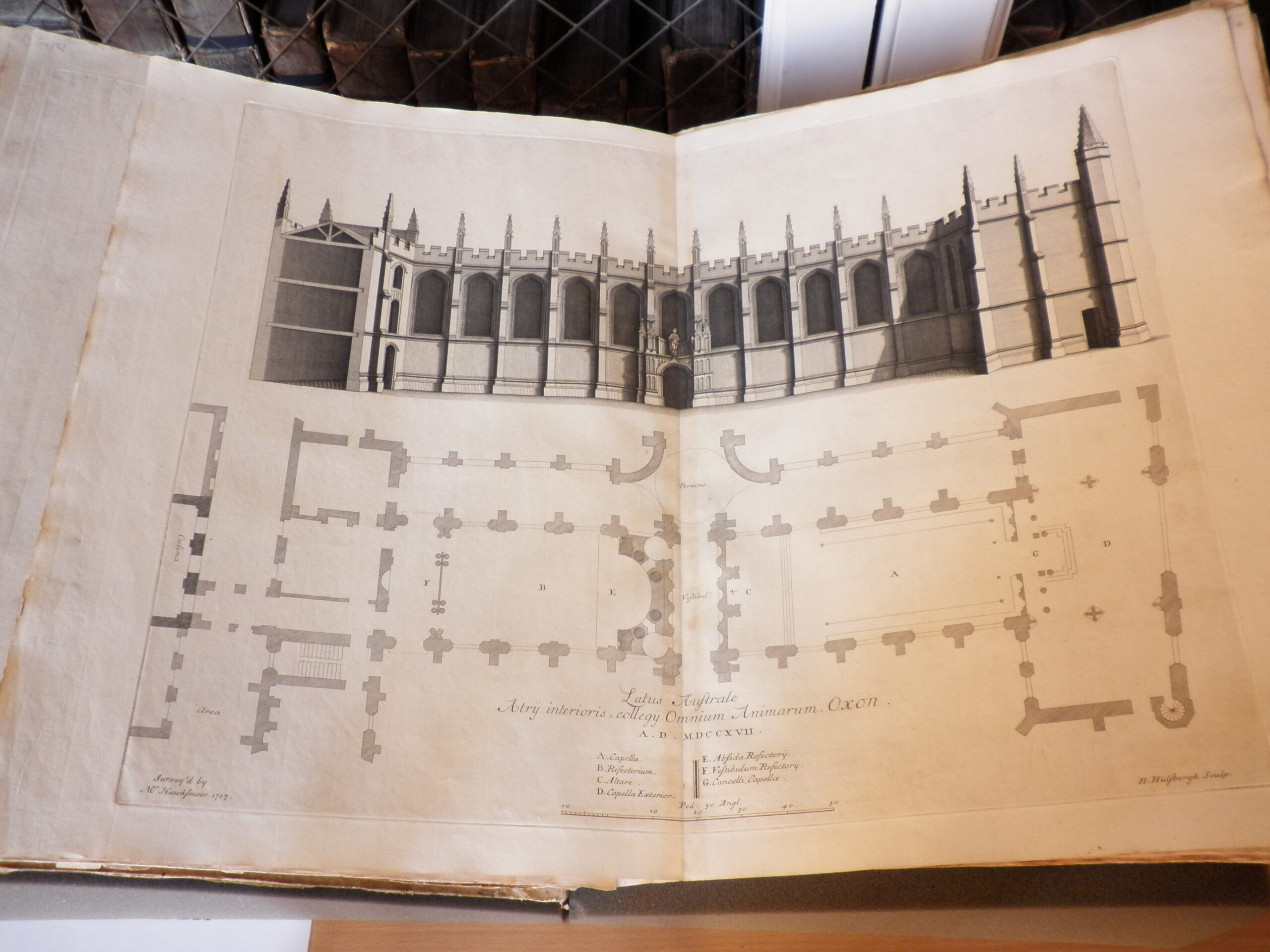

George Clarke (1661-1736), Fellow of All Souls, Tory politician, architect and collector, held various offices under the Tories, including secretary at war to William III, before being appointed to the commission of the Admiralty in 1710. He was also secretary to George, Prince of Denmark. At the death of Queen Anne, however, he lost office. Nonetheless, Clarke remained MP for the University and he was able to indulge his architectural interests, playing a part in most of the University building projects of his time. He designed, for example, the Warden’s Lodgings at All Souls and completed Henry Aldrich’s designs for the Library at Christ Church; he worked with Hawksmoor and Thornhill at Queen’s College; and collaborated with Hawksmoor on the Codrington Library at All Souls. He collected not just books, but also drawings and prints – all of which were left to Worcester on his death in 1736.

Latus Australe Atrij interioris, collegij Omnium Animarum. Oxon. (Oxford, 1717); designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor; engraved by Henry Hulsbergh; private publication

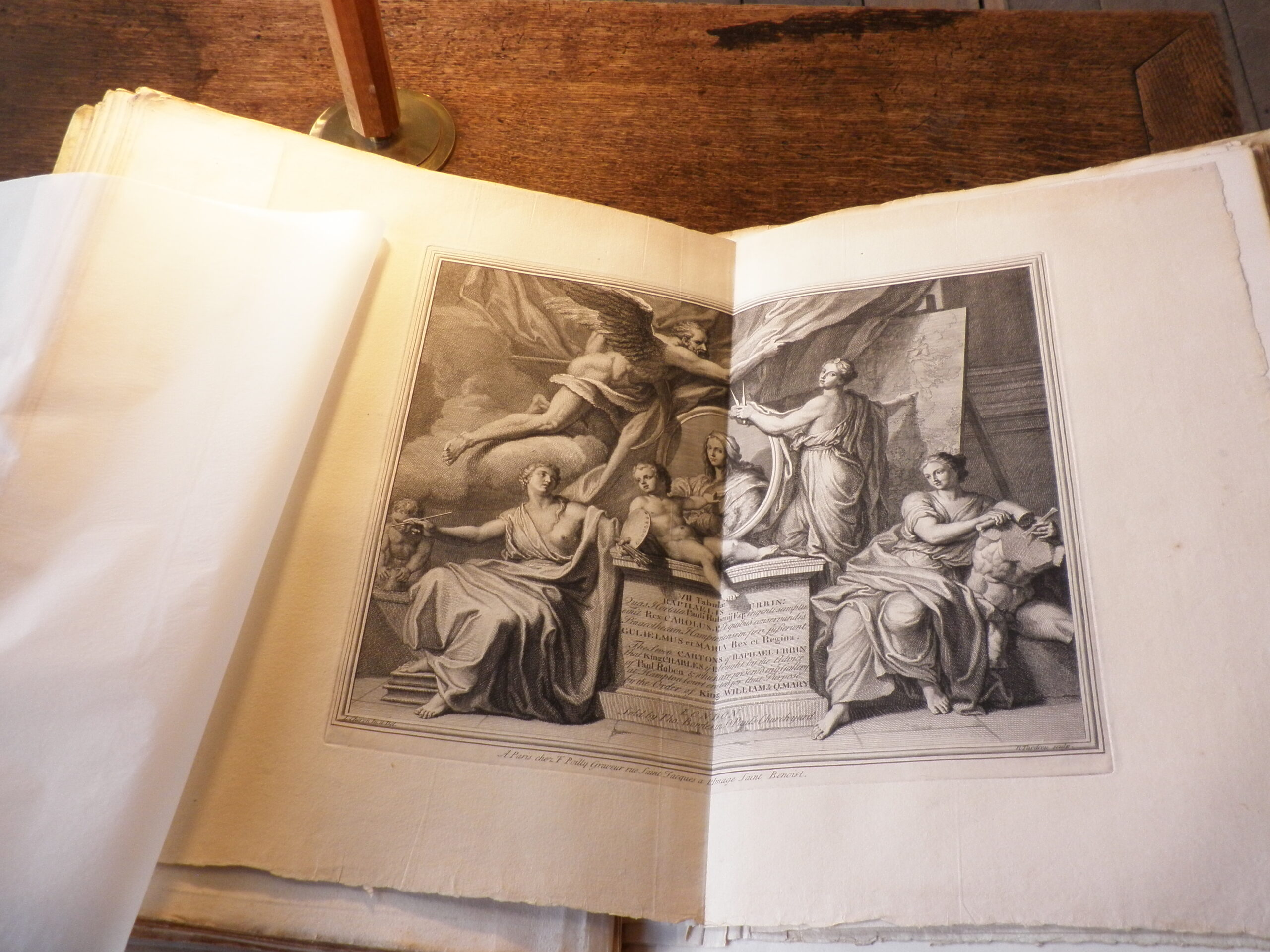

For his print collection, Clarke tended to buy modern, contemporary, French prints, ‘considering them better engraved and more informative than sixteenth-century ‘antiques’ ’ (Clayton, ‘The Print Collection of George Clarke’, page 124). Indeed, the informational content of the print was important for Clarke, who kept his prints untrimmed, preserving all the textual information on them. As Clayton notes, this is because the texts often provided information about the collections where paintings were held, in addition to a painting’s owner, size, and provenance, all of which ‘responded to an increasing interest in connoisseurship’ among print collectors in the late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-centuries (Clayton, ‘The Print Collection of George Clarke’, page 125).

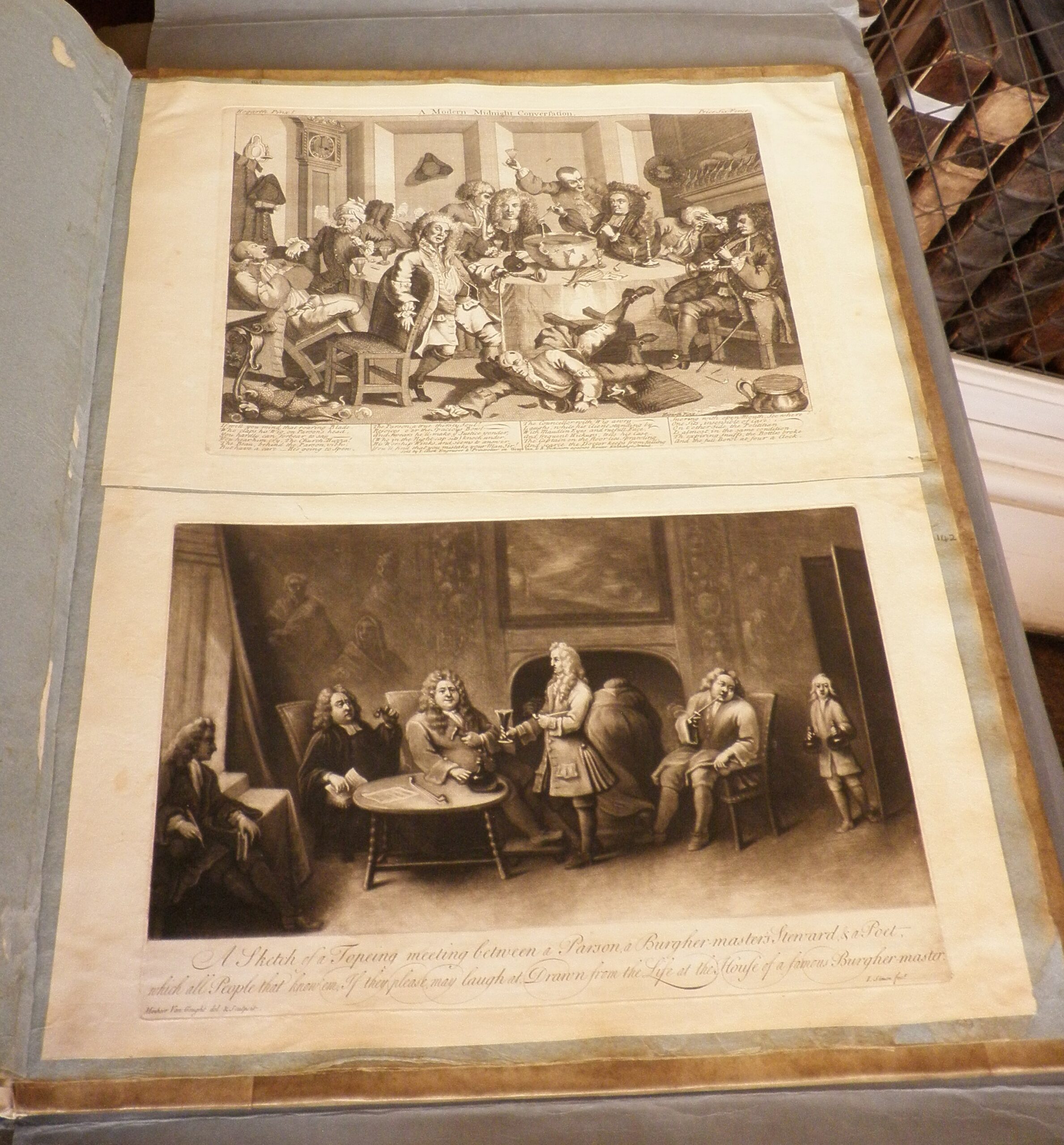

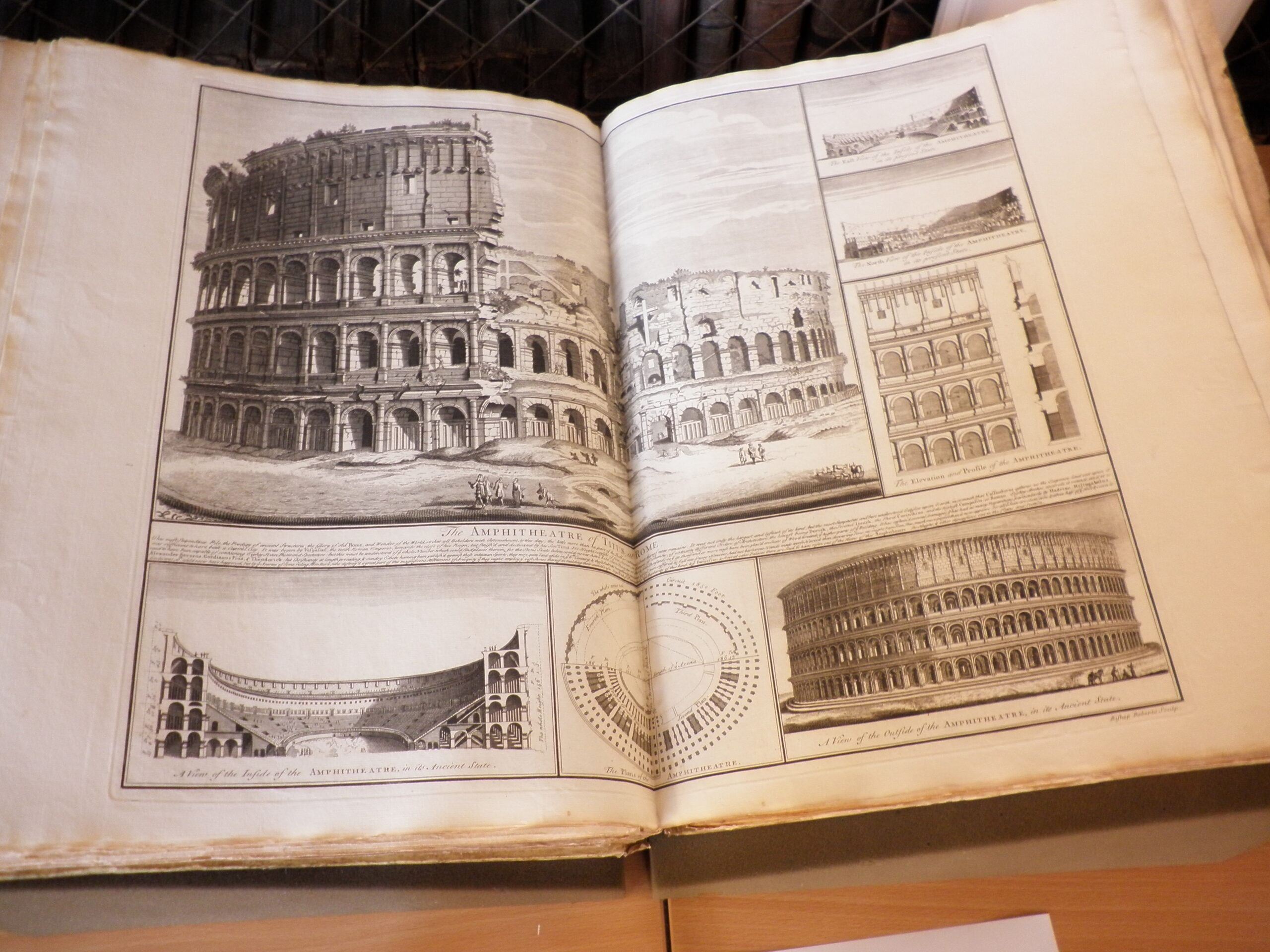

Clarke intended his collection for use. The prints have been arranged into three main subject categories (architecture, portraiture, and painting) and within those Clarke has made further subdivisions. Unsurprisingly given his architectural interests, that part of the collection is by far the greatest and the architectural albums are the most formally organised volumes, coherently arranged by place. Clarke separated portraiture from painting, with a focus on portraits of 17th– and 18th-century individuals, that is, historical figures of his own and his father’s generations. Finally, in painting, Clarke was devoted to particular painters: Raphael, Poussin, Antoine Coypel, Charles le Brun, Salvator Rosa – prints after these and other painters were each arranged in their own album.

Seven Cartons of Raphael Urbin that King Charles ye I bought (London, 1721) / designed by Raphael; engraved by Nicolas Tardieu; published by Thomas Bowles and Francois de Poilly

As Ledbury explains:

“[Clarke] had a particular interest in French architecture, both at Versailles and in the Paris, that, in the last years of Louis XIV’s reign and in the Regency was becoming a magnet for new money, and new architectural ambition. He also collected contemporary prints after key antique and Renaissance works, particularly those of Raphael and Poussin. All this was familiar territory for the Amateurs of the early eighteenth century, but Clarke’s collection notably includes prints after contemporary art (Watteau, Charles-Antoine Coypel and even early Hogarth prints found their way into his collection).”

Top: A Modern Midnight Conversation (London, 1733) / designed by William Hogarth; engraved by John Clark; published by John Clark and Bispham Dickinson; Bottom: Sketch of a Topeing meeting / engraved by John Simon

The collection is interesting not only in itself, but also for the archival pieces that accompany it: papers from Clarke’s friend the Anglo-Irish painter Charles Jervas (1675-1739) describing the arrangement of Raphael paintings in the Vatican; correspondence from the Secretary of State for Ireland Edward Southwell (1671-1730) in 1726 describing the print market in Rome; wrappers for the delivery of prints ‘To Dr Geo: Clarke, Oxon’; and Clarke’s ‘shopping lists’ for Jervas, listing prints Clarke wanted Jervas to acquire for him, drawn up using the print catalogues of the de Rossi printing house.

Such pieces give some idea of how Clarke acquired his prints. Clarke owned houses in both Oxford and London, major printing locations, and so there is little mystery over his acquisition of English prints. He travelled to Paris and Fontainebleau for three months from May 1715, so it is likely that he bought some of his French prints on the French market. Indeed, ‘Paris, Juillet 1715’ is inscribed on the front endpaper of Album 38 (a collection of plans and elevations by the French engravers Jean and Daniel Marot). Yet Clarke, despite his great interest in Italy, never made it there and so, as these letters and lists make clear, he had to rely on friends acting as agents to purchase prints for him on the Italian market. Indeed, in the end, it was only through his prints and other collections that Clarke could travel in Italy.

The Amphitheatre of Titus at Rome (London, 1730) / engraved by Bishop Roberts; private publication

Mark Bainbridge, Librarian

Bibliography

- Clayton, T., ‘The Print Collection of George Clarke at Worcester College, Oxford’, Print Quarterly, vol. IX, no. 2 (June 1992), pages 123-141