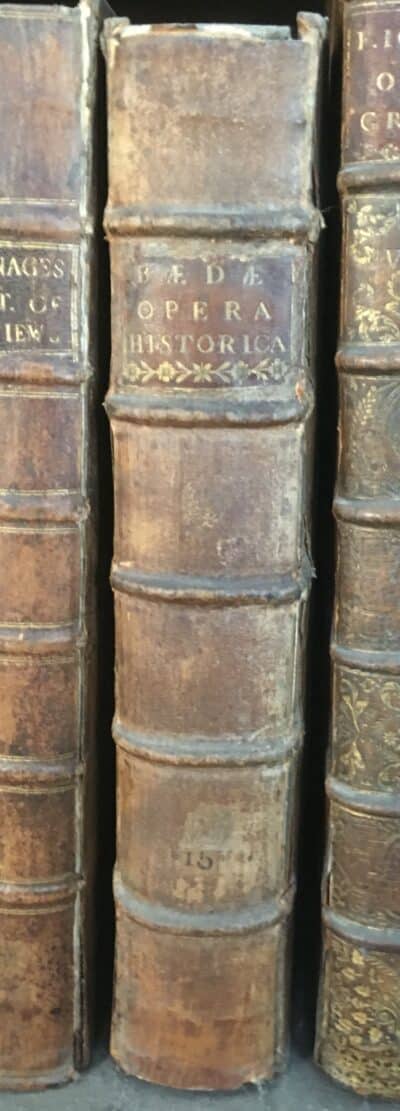

James Campbell’s antiquarian copy of Bede’s Ecclesiastical history

31st January 2019

James Campbell’s antiquarian copy of Bede’s Ecclesiastical history

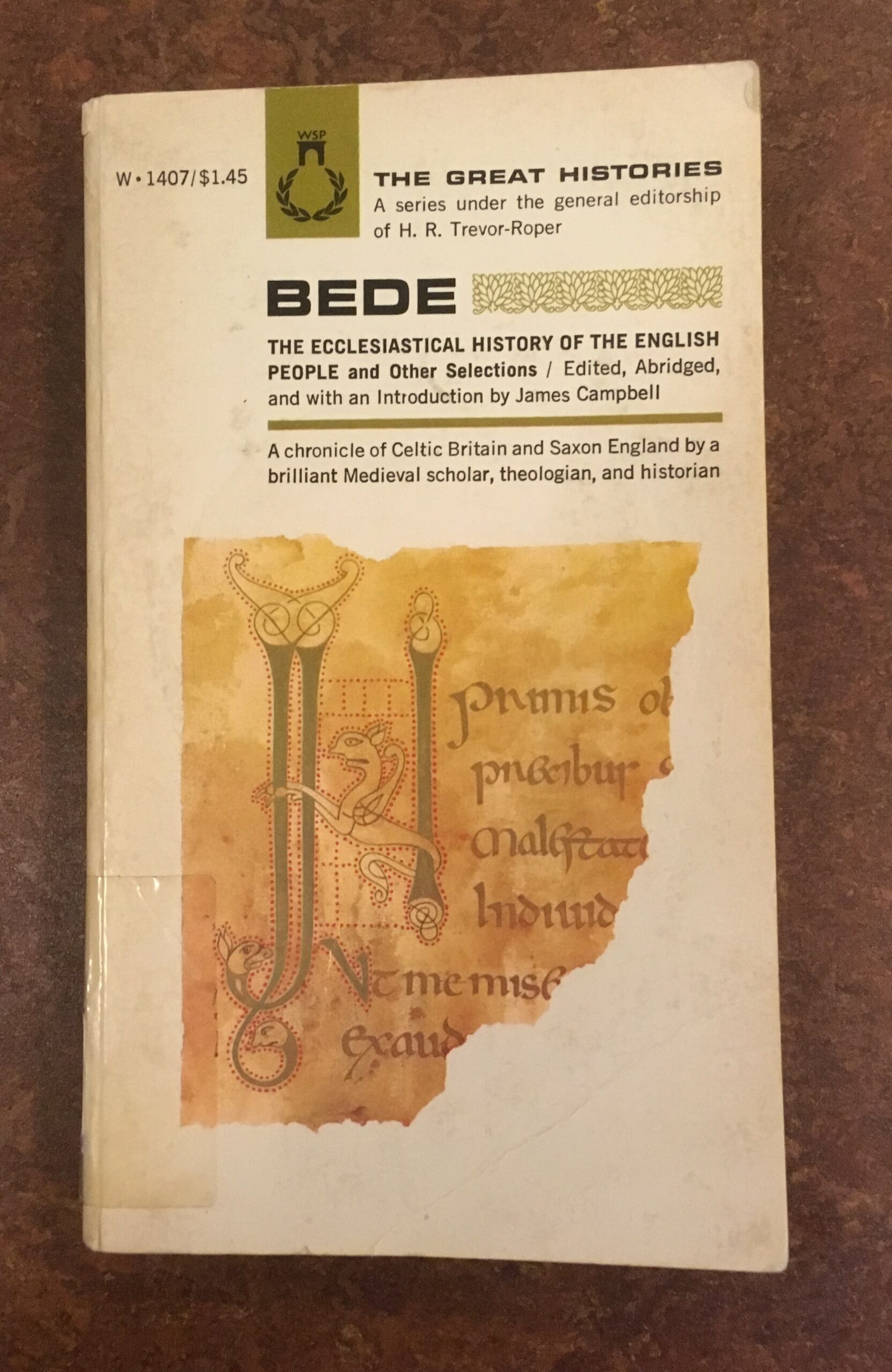

Bede, Historiæ ecclesiasticæ gentis Anglorum ... Cura et studio Johannes Smith. Cambridge: typis academicis, 1722.

A 1722 edition of Bede’s Historiæ ecclesiasticæ gentis Anglorum, the Ecclesiastical history of the English people, bequeathed to Worcester by the late James Campbell is the focus of this first blog post of 2019. Several generations of Old Members will not need telling that this eminent Anglo-Saxon historian was for over forty years a Fellow and Modern History Tutor at the College, inter alia serving as Fellow Librarian and Keeper of the Archives. Appropriately, his benefaction helped fund Worcester’s new archive facility and also brought some 37 volumes of his antiquarian books to the college (plus a selection from his very substantial collection of modern ones). At the time of his death, Campbell had been a Fellow and Emeritus Fellow for a fifth of the college’s history, so even if this copy of the Ecclesiastical history has been in the Library a relatively short time it has a noteworthy connection to Worcester and its intellectual life.

The 1722 edition was an important milestone in the study of the Venerable Bede (673-735) – the first English thinker to gain a truly European reputation. Notable as a theologian, he is now best known as an historian – and in that role helped to popularise use of the Anno Domini dating system and to shape early notions of English identity (Campbell, 2004/2008). Continental editions of his Ecclesiastical history had appeared from the earliest period of printing, the first in Strasbourg c.1474-82, and there were various reprintings and subsequent editions over the next two hundred years. It was not until the 1640s, however, that the first insular edition appeared: edited by Abraham Whelock and published in Cambridge. An appreciable achievement, its limitations highlighted the need for further study. This would ultimately be undertaken by John Smith, a Canon of Durham Cathedral, where Bede is buried, and Rector of Bishopswearmouth, a parish close to the sites of the twinned monasteries of Monkwearmouth and Jarrow where Bede spent his monastic life.

Engraving of Durham Cathedral from Smith’s edition

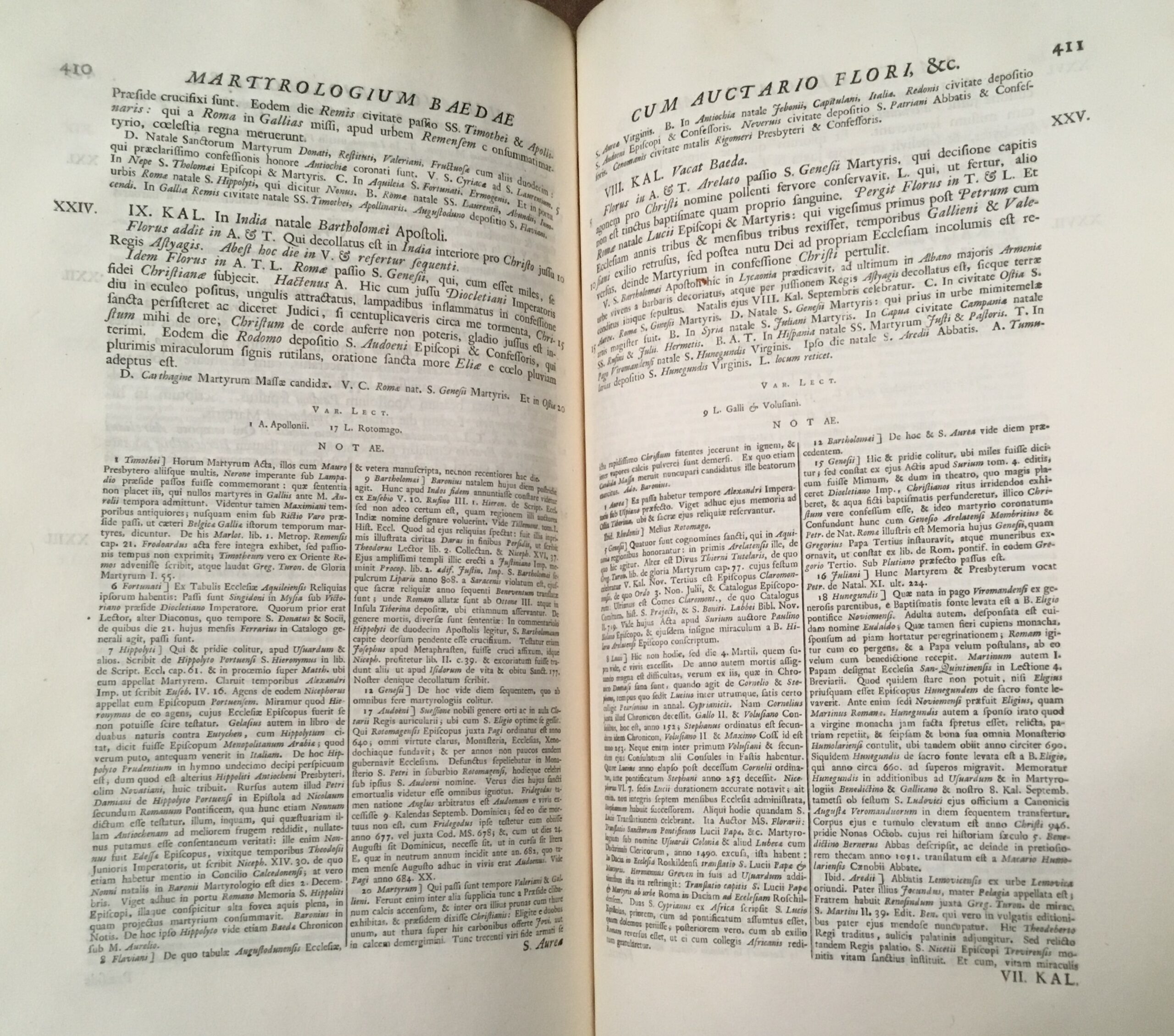

Smith produced what has been fulsomely described not just as “the first truly critical edition of Bede’s Ecclesiastical History” but “perhaps the most perfect single book of the greatest age of Anglo-Saxon historical learning” (Douglas, p. 62). For the twentieth century editors of Bede’s History, Smith’s edition simply “left little more to do”, and held the field until Plummer’s famous 1896 Venerabilis Bedae opera historica (Bede/Colgrave & Mynors, pp. lxxii-iii). Plummer himself had called it “a truly monumental work” (Bede/Plummer, p. lxxx). In the age of the internet and online digital reproductions, it is easy to underestimate the difficulties of attempting such scholarship. Plummer lived in a period of railways and steamships; with Smith we are in the era of turnpikes. It is not surprising then that Smith relied on the eighth-century manuscript of Bede recently purchased by John Moore, Bishop of Ely. That diocese included Cambridge, where Smith had been an undergraduate and would spend his last years pursuing his Anglo-Saxon studies. Smith also consulted manuscripts now held by the British Library, including two from the celebrated collection of Sir Robert Cotton (one later badly burned in 1731). Those two – with the Moore MS – represent three of the five earliest manuscripts of the Ecclesiastical History known even now. Smith’s approach to textual criticism was the sound one of working from the earliest versions of the text, using Moore’s MS as a base, which he supplemented with reference to others. The task, initially planned by Thomas Gale, was a formidable one. It occupied Smith for fourteen years (Douglas, p. 62) and proved deleterious to his health, which he impaired by “too assiduous and indefatigable application” to his books, dying in 1715 after a short illness “occasioned by a weakness of stomach, grown unable to do its office” (Biographica Britannica, p. 3725). Only a quarter of the text was ready at the time of his death and the project was completed by his young son, George (Bede/Plummer, p. lxxx). Paging through the Smith edition the scale of the work underpinning it is evident from the extensive footnotes.

Smith’s footnotes

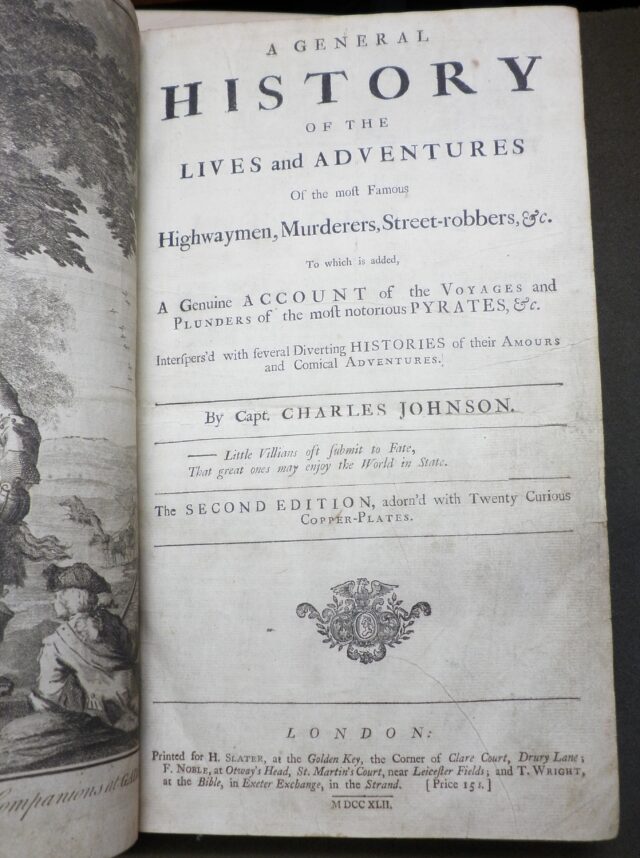

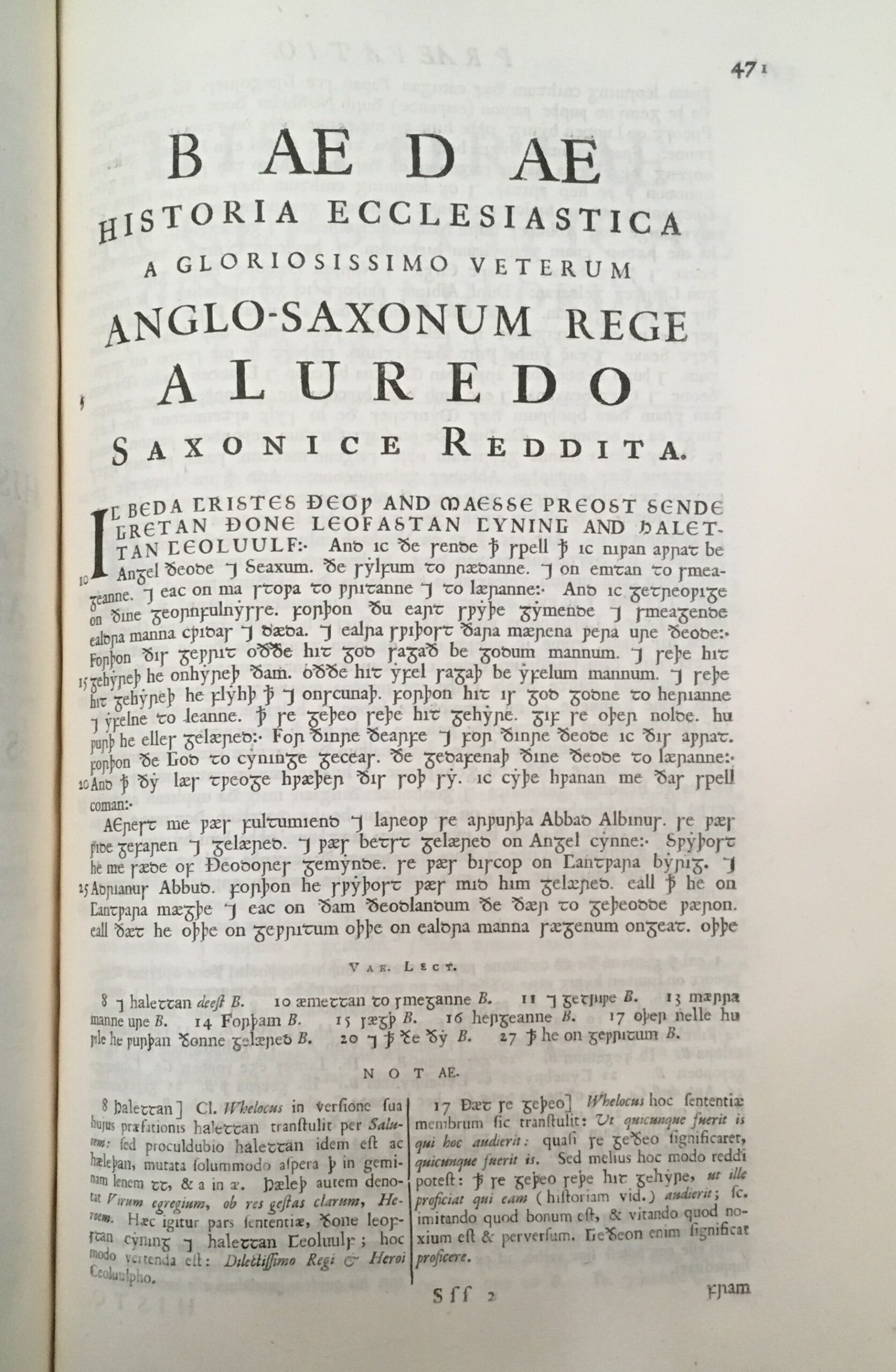

In reality it is misleading to refer to Smith’s edition as simply being of the Ecclesiastical history, because the Latin text occupies only a quarter of a folio volume running to more than 800 pages. What he prepared was in fact a collection of Bede’s historical works. This included the history of the abbots of Wearmouth and Jarrow, both the prose and verse lives of Saint Cuthbert (like Bede buried in Durham Cathedral), a translated life of Saint Felix, Bede’s martyrology and his letter to Archbishop Egbert of York – a text that in lectures James Campbell advised Oxford history finalists to keep “under their tear-stained pillows”. The long appendix contained “a valuable series of Anglo-Saxon charters from Mercia whose originals have since been lost” (Douglas, p. 63). Like the earlier Cambridge edition, which had published it for the first time (with Latin and Anglo-Saxon in parallel columns), there was also a second version of the Ecclesiastical history: the Alfredian Anglo-Saxon translation of the text. This necessitated the cutting of a new set of types by the University Press at Cambridge. On top of the difficulty for the compositor of rendering a text with such an elaborate scholarly apparatus, centuries before word processing, thus came the additional problem of rendering 200 pages in an unfamiliar alphabet. As such the Smiths and their printer achieved a typographical tour-de-force.

Smith’s Anglo-Saxon text of Bede

Whelock’s Anglo-Saxon and Latin texts

Smith’s edition is imposing as a physical object, like similar antiquarian projects of the time. Indicative of its scale and consequent cost was the need in 1713 to issue a classified advertisement inviting subscriptions (http://estc.bl.uk/T200509). It is lightly illustrated. There are three engravings by Michael van der Gucht, and Campbell would certainly have approved of the large folded map. Campbell’s copy is handsomely bound in blue leather with gold decoration, mainly to the panelling on the spine, but the binding is of no great age – probably Victorian – and shows signs of wear. However, it is the volume’s intellectual attributes that are perhaps most significant. This makes it an apt work for Worcester Library to receive from a leading scholar of Anglo-Saxon history, especially one so aware of the contributions made by his predecessors in previous centuries.

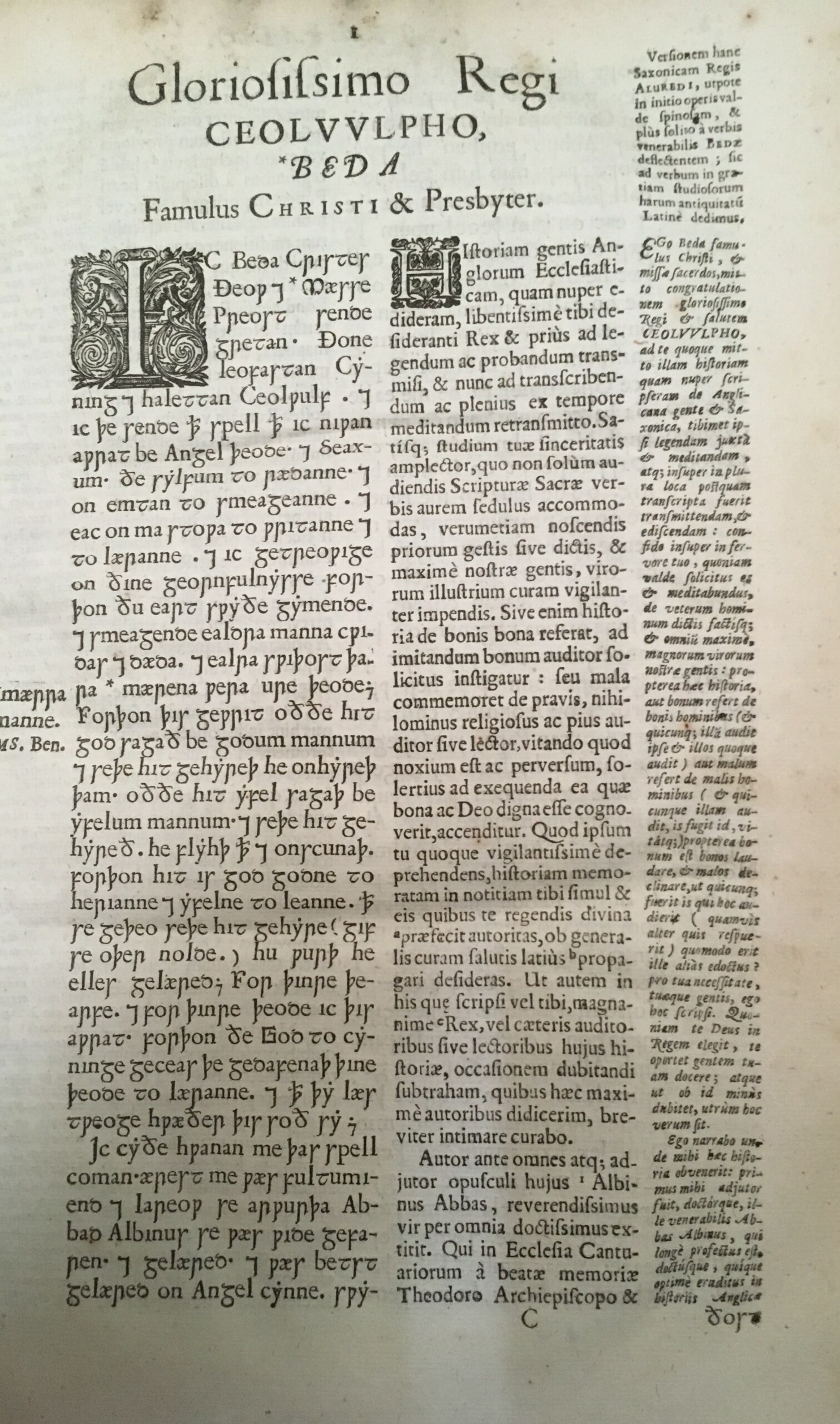

Early Worcester Library catalogue entries for Bede

As a major piece of antiquarian scholarship it is unsurprising that Smith’s edition should feature in the collections of three-quarters of the Oxford colleges extant in 1722. This includes Worcester, which has two additional copies. One came with the founding benefaction of George Clarke, received in 1736, and another probably from the omnivorous nineteenth-century bibliophile and Worcester Librarian, H.A. Pottinger. In an historic library, it is difficult not to think – perhaps fancifully – about the readers who might have consulted a particular book, and the uses to which it has been put. This is especially true in a college library, like Worcester’s, that exists as part of a living academic community. It seems implausible, given Campbell’s links to the Library and long-running engagement with the author, that he did not consult the copies of Bede held by his own college. (Interestingly, “Idem” in the catalogue extract above seems, on a quick inspection, to be a 1601 Cologne edition of Bede!)

- Sir George Clarke’s copy of the 1722 Bede

For another major Anglo-Saxonist, the late Patrick Wormald, Campbell’s lectures on Bede for the old Modern History “Prelims” (then unlike now sat at the end of students’ first term in Oxford with the text read in Latin) had an “electrifying” effect in 1966 (Maddicott & Palliser, p. xiv). In the same year, Campbell’s chapter on Bede in Latin historians was published (Maddicott & Palliser, p. xxxix; Campbell, 1986, pp. 1-27). Campbell’s written output on Bede stretched forward more than forty years, culminating in the biographical article in the Oxford dictionary of national biography (Campbell, 2004/2008) and a piece on Bede’s social and political contexts in the 2010 Cambridge companion to Bede (Campbell, 2010, pp. 25-39). The subject-matter of the last is characteristic of Campbell’s intellectual endeavour to see beyond what Bede himself had written.

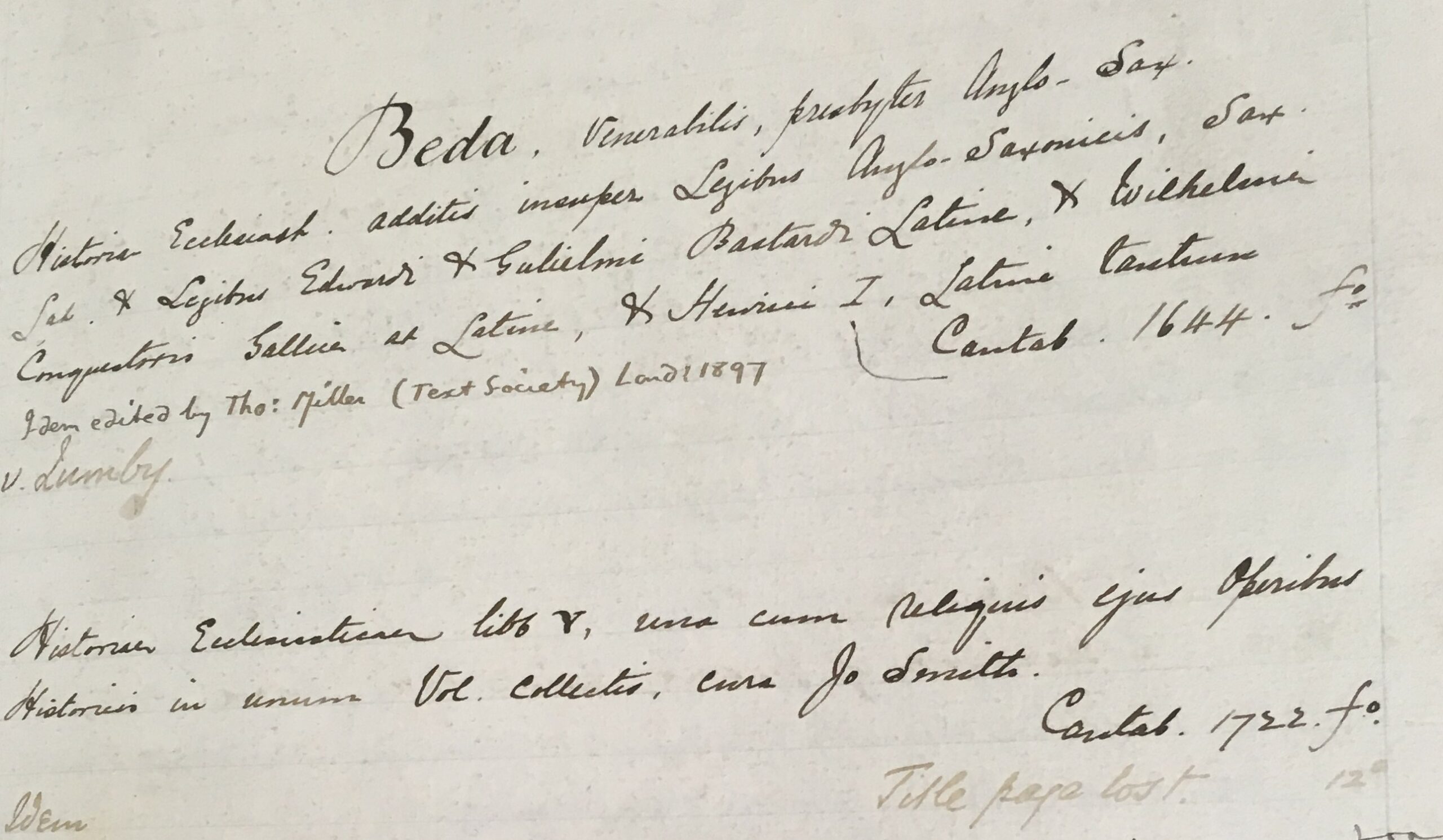

Campbell’s popular edition of Bede

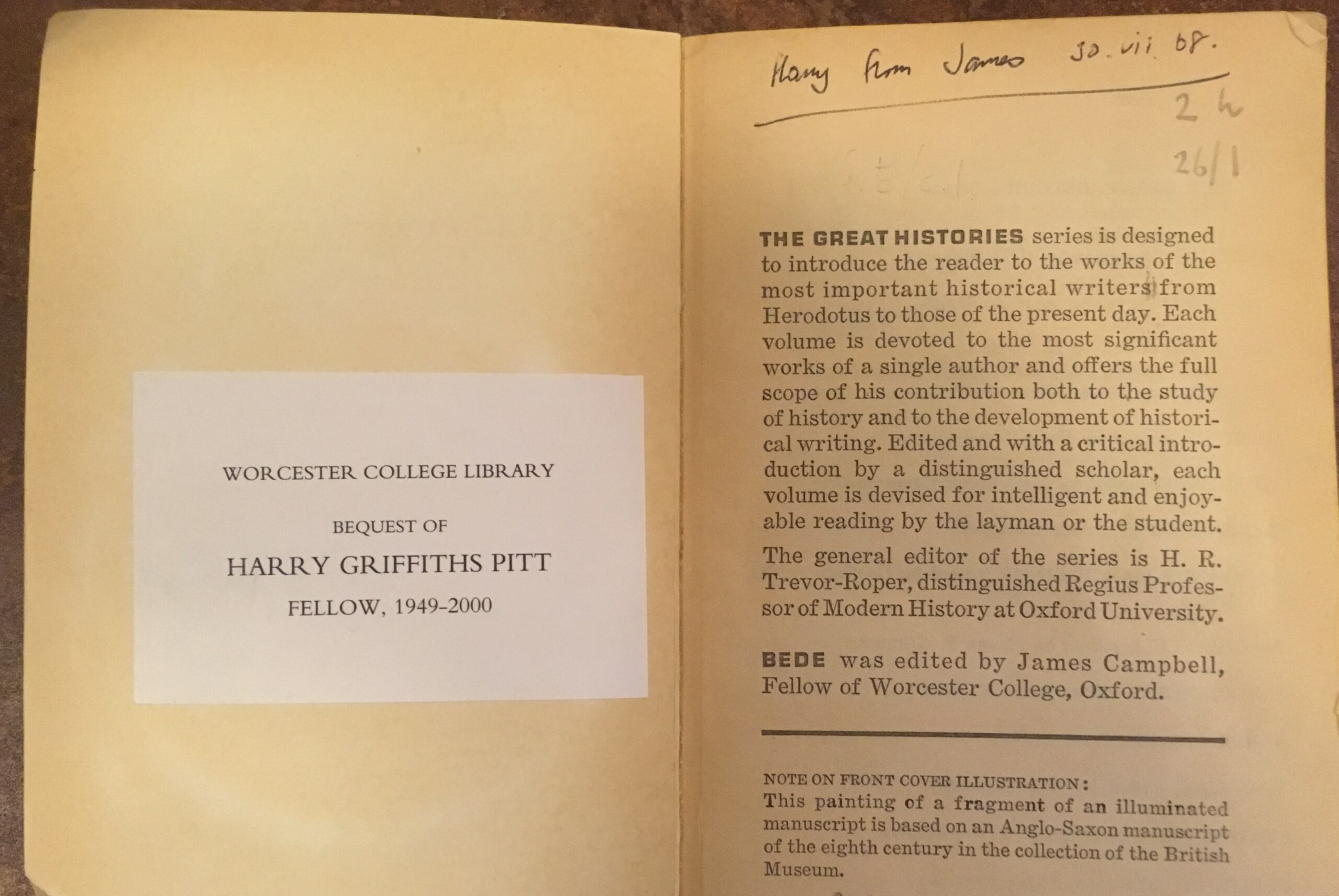

Looking at editions of Bede, there is an agreeable circularity, because Campbell in 1968 brought out a popular edition of Bede’s key historical works in translation, including an abridged version of the Ecclesiastical history. Alongside his own translations of the History of the abbots and a Life of Saint Cuthbert, he “considerably revised” a translation of the Ecclesiastical history made by J.A. Giles in the nineteenth century, citing an 1843 edition that can be found in Worcester Library (Bede/Campbell, p. xxxv). This, in fact, is itself an adaptation of the translation by John Stevens published in 1723, which Giles had “corrected without scruple” (Bede/Giles, vol. II, p. 20). Stevens’ translation, printed in octavo for a more popular audience, had in turn been based on Smith’s edition of a year earlier. There is then a direct intellectual line of descent connecting Smith in the eighteenth century and Campbell in the twentieth. Another nice point is that the copy of Campbell’s popular Bede came to the Library from his colleague, and fellow Modern History Tutor of long duration, Harry Pitt, to whom it had been presented by Campbell himself.

Bookplate and signature in Campbell’s edition of Bede

If this volume is not perhaps a treasure by dint of obvious criteria like – for example – rarity or spectacular visual qualities, less tangible factors make it valuable. For Worcester – and for Worcester historians especially – the volume is definitely treasurable.

Harry Pitt, James Campbell, & Worcester historians

Ben Arnold, Assistant Librarian

Bibliography

- Bede, Historiæ ecclesiasticæ gentis Anglorum, edited A. Whelock (Cambridge, 1644).

- Bede, Historiæ ecclesiasticæ gentis Anglorum, edited J. Smith (Cambridge, 1722)

- Bede, The complete works of Venerable Bede, edited and translated J.A. Giles (12 volumes, London, 1843-4).

- Bede, Venerabilis Baedae operae historica, edited C. Plummer (2 volumes in 1, Oxford, 1896, reprinted 1975)

- Bede, The ecclesiastical history of the English people and other selections, edited J. Campbell (New York, 1968).

- Bede, Bede’s Ecclesiastical history of the English people, edited and translated B. Colgrave & R.A.B. Mynors (Oxford, 1969).

- Biographia Britannica, 1747-1766 (6 volumes in 7, Hildesheim, 1973), pages 3723-33 {contains biographies of John and George Smith}.

- Campbell, J., Essays in Anglo-Saxon history (London, 1986).

- Campbell, J., “Bede (673/4–735), monk, historian, and theologian”, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2004, revised 2008): https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/1922.

- Campbell, J., “Secular and political contexts”, in The Cambridge companion to Bede, ed. S. Degregorio (Cambridge, 2010), pages 25-39.

- Douglas, D.C., English scholars, 1660-1730 (Second, revised edition, London, 1951).

- Maddicott, J.R. and D.M. Palliser (editors), The medieval state: essays presented to James Campbell (London, 2000).

- Thacker, A., “James Campbell” (2016): https://www.worc.ox.ac.uk/news-events/news/professor-james-campbell-remembered