Ex libris James Campbell: William Dugdale’s Antiquities of Warwickshire

30th November 2016

Ex libris James Campbell: William Dugdale’s Antiquities of Warwickshire

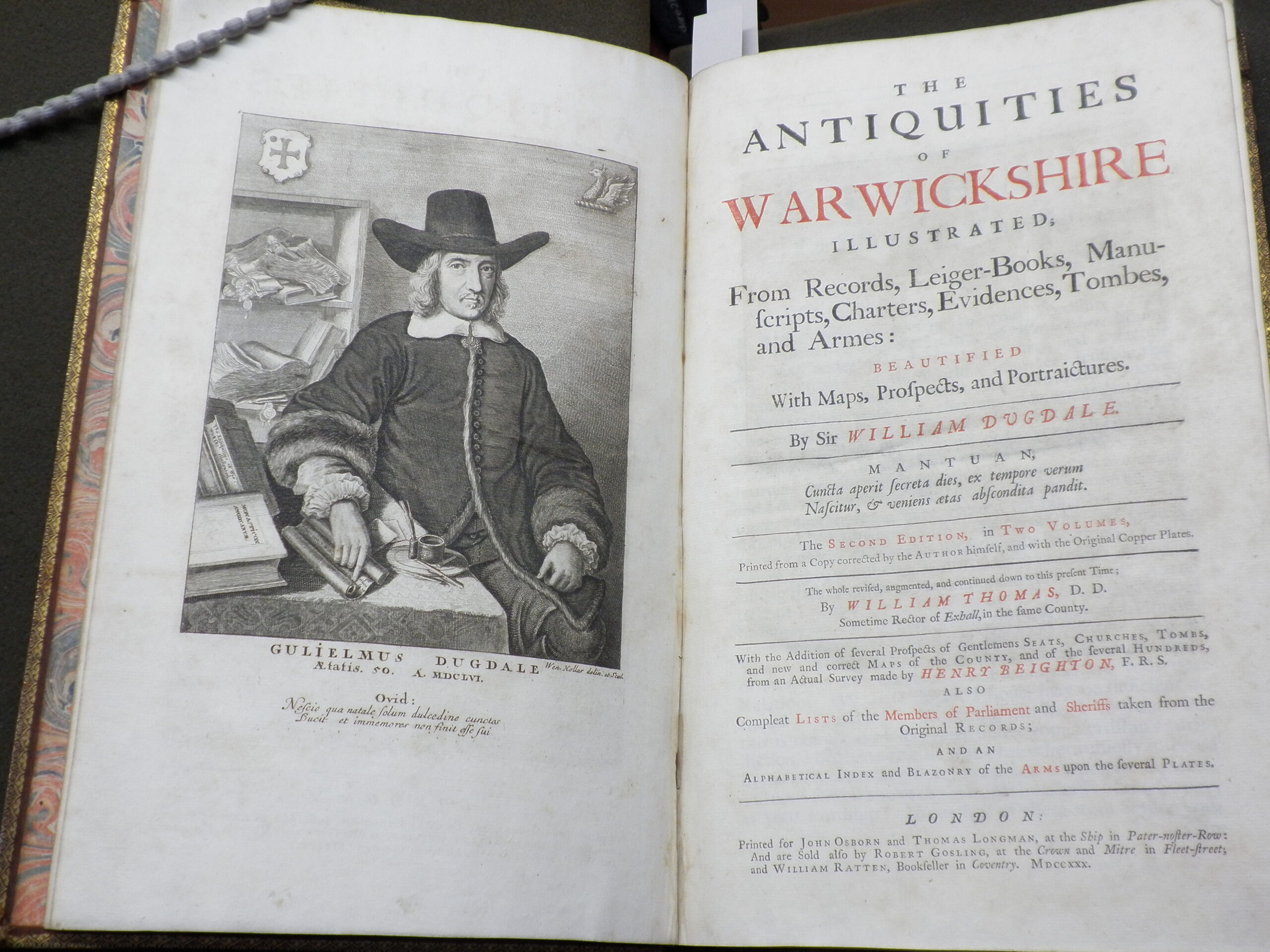

The antiquities of Warwickshire illustrated; from records, leiger-books, manuscripts, charters, evidences, tombes, and armes: beautified with maps, prospects, and portraictures. The second edition.

London: printed for John Osborn and Thomas Longman…, 1730.

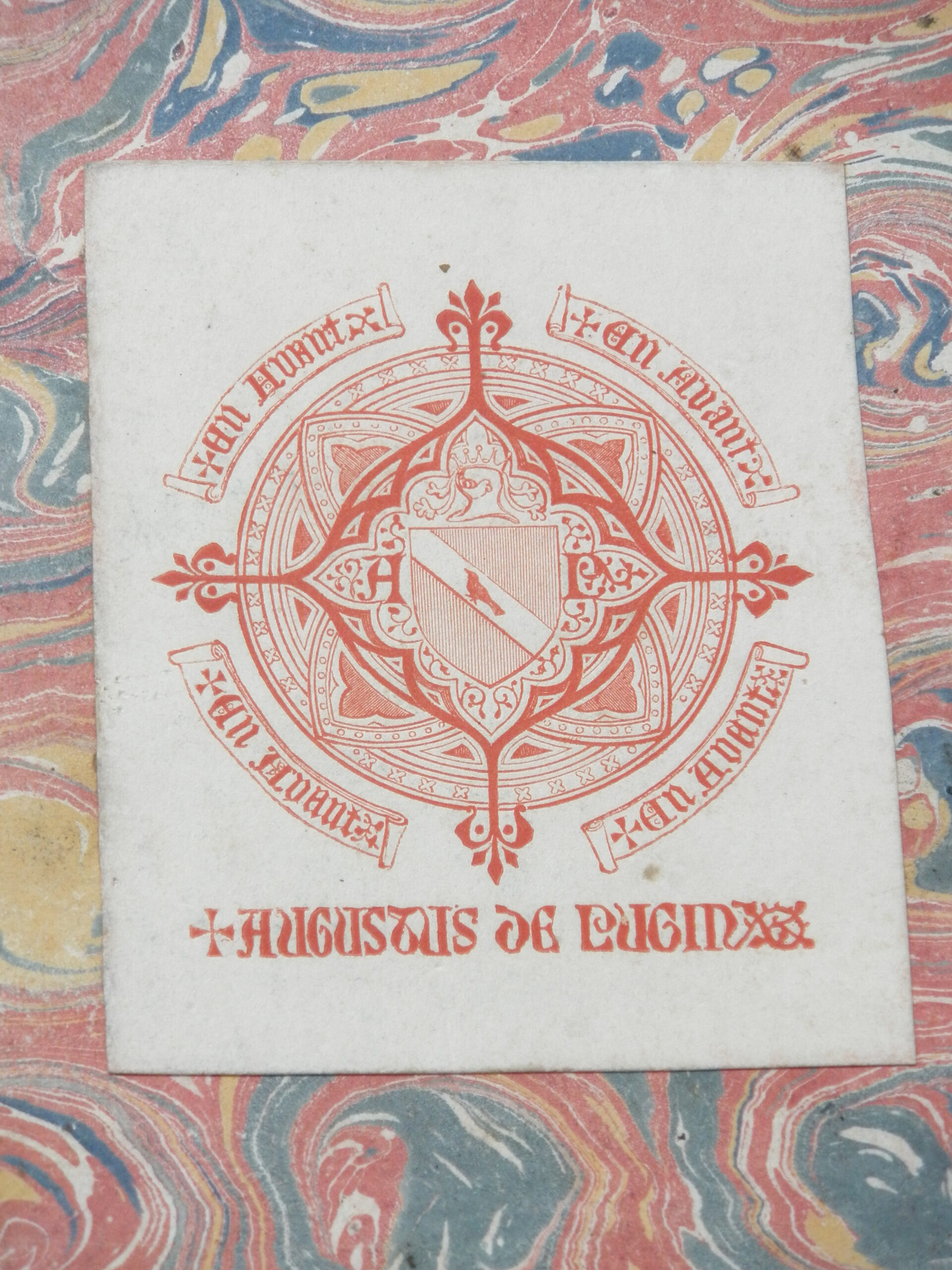

James Campbell’s personal bookplate (from a book in his modern – not antiquarian – collection)

On 3rd November 2016, the College and University celebrated the life of Professor James Campbell (1935-2016), Tutorial Fellow in History at Worcester College from 1957 to 2002. In his honour we have chosen as November’s treasure one of thirty-three titles left by Professor Campbell to Worcester College Library, where he was Fellow Librarian from 1977 to 2002. These antiquarian books (dating predominantly to the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries) reflect Professor Campbell’s scholarly interests (in the Anglo-Saxon and medieval world) and complement existing collections. In considering them, one small grouping emerges: works by early English antiquaries such as Sir Henry Spelman (1563/4-1641) and John Selden (1584-1654); their successors in the next generations, Sir William Dugdale (1605-1686) and Thomas Madox (1666-1727); and also works of 19th-century antiquaries such as T.D. Whitaker (1759-1821) and Alfred Suckling (1796-1856). From among these, we have chosen the lavishly illustrated second edition of Sir William Dugdale’s Antiquities of Warwickshire, ‘the consummate county history of the seventeenth century, as admired now as it was at its first publication in 1656, the culmination of a tradition of such writing that goes back to William Lambarde’s Perambulation of Kent of 1576’ (Parry, ‘The antiquities of Warwickshire’, page 10).

Dugdale’s Antiquities of Warwickshire is the product of 25 years’ work, based not only on Dugdale’s own research, but also on materials gathered by William Burton (author of The description of Leicestershire, 1622), Sir Thomas Shirley, and Sir Simon Archer. The first edition appeared in 1656, and in its frontispiece Dugdale was presented as a scholar: he is shown with writing instruments to hand and surrounded by the manuscripts, archival rolls and books that were such important source material for his work and which are frequently cited in the extensive footnotes to Warwickshire. We can note that his coat of arms and crest are included in the top corners of his portrait – Dugdale was also a herald (appointed blanch lyon pursuivant in 1638, eventually becoming Garter king of arms in 1677) and the link with genealogy is important in the Antiquities. Although one can be forgiven for expecting otherwise given the title of the work, rather than treat ancient monuments and buildings (‘Antiquities’), the book’s focus is undoubtedly genealogical, especially on gentry families, their descents and land-holdings (see Parry, ‘The antiquities of Warwickshire’, page 10). In his Warwickshire Dugdale looked at the history of medieval institutions (the monasteries, the legal system, and the aristocracy), linking local matters with national affairs (see Parry in ODNB, s.v. ‘Sir William Dugdale’).

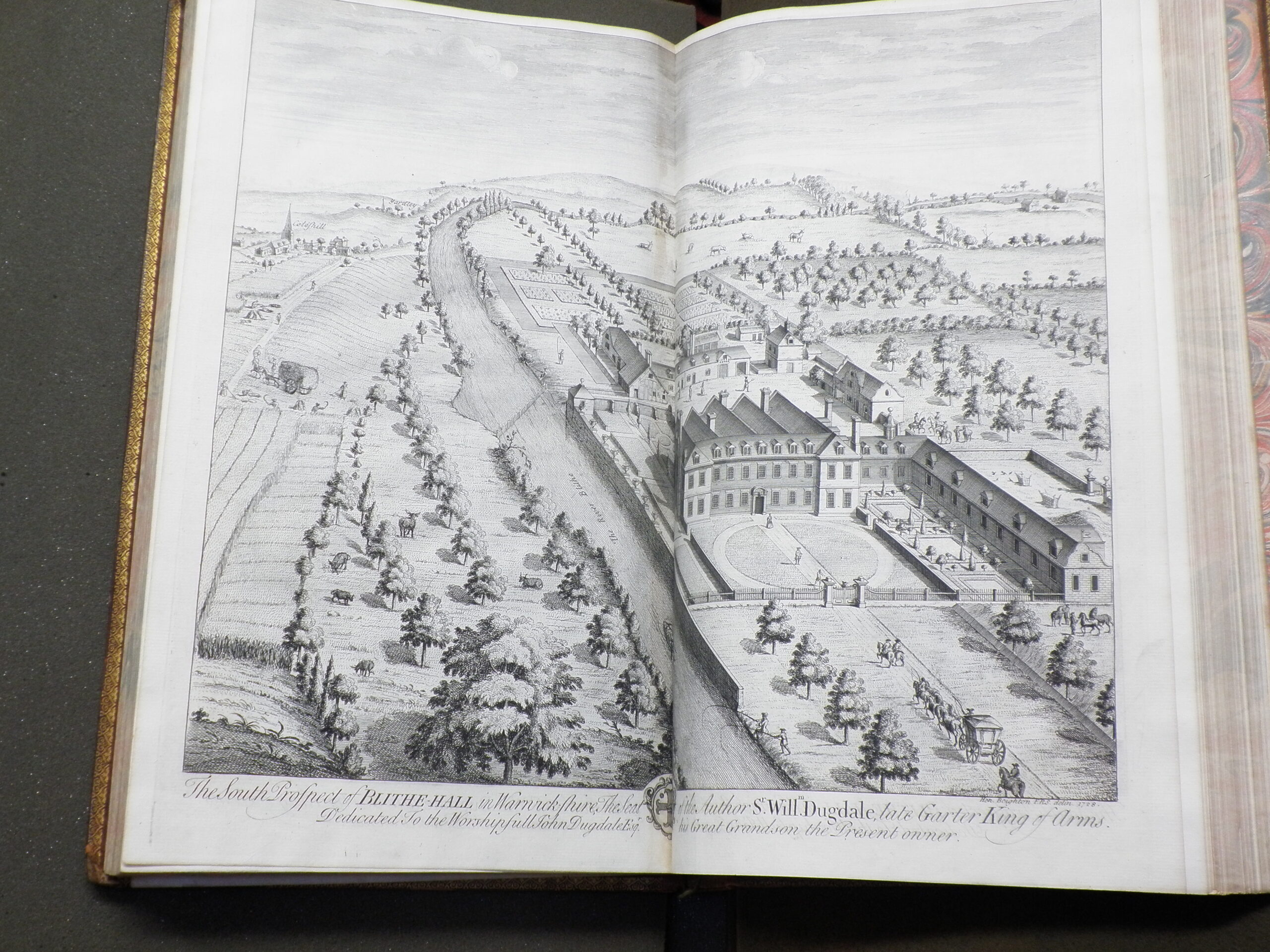

The second edition was the work of the Reverend William Thomas, sometime Rector of Exhall, a village near Alcester in Warwickshire. Thomas checked records and corrected mistakes. In addition to the illustrations of the first edition, he also commissioned several new prints, including (in the words of the title page) ‘several prospects of gentlemens seats, churches, tombs, and new and correct maps’, among them a view of Dugdale’s own home, Blyth Hall, as it stood in the days of his grandson, when the old house had been converted into ‘a fashionable Queen Anne mansion’ (Jenkins, ‘Dr Thomas’ edition…’, page 13).

‘The south prospect of Blithe Hall’, between pages 1050-1051

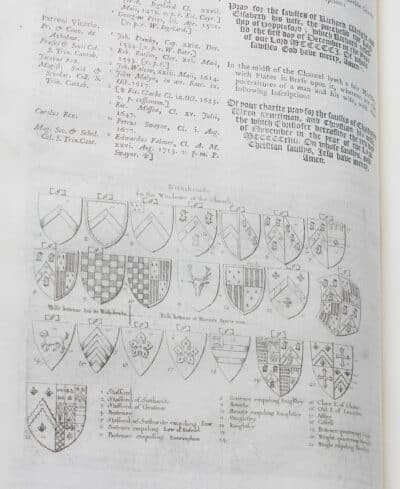

One of the notable points about Antiquities of Warwickshire is the sheer number of illustrations: the first edition had nearly 200, which provided visual evidence in support of Dugdale’s text (see Roberts, Dugdale and Hollar). Marion Roberts has classified the images in three types: heraldic, topographical, and costume (Roberts, Dugdale and Hollar, page 23 and passim).

- page 216 – from the windows of the church at Withibrooke

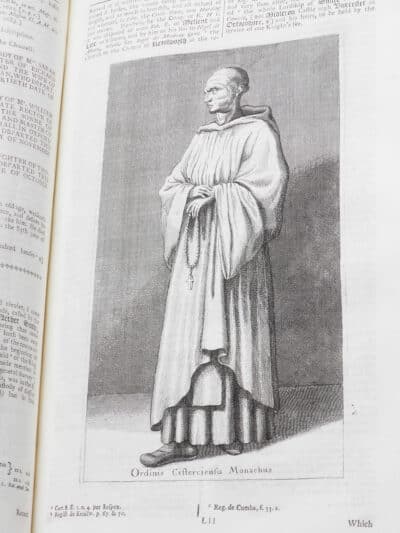

- page 221 – Cistercian monk

The heraldic images documented family lineages, with visual details (gathered from Dugdale’s researches in local churches) conveying authority. Topographical prints provided visual information about landscapes. The costume prints, which focus particularly on religious costumes such as the habits of monks, friars and nuns, are thought to have ‘quietly called attention to the monastic houses supported by past generations of Warwickshire’s gentry’ (Roberts, p.23).

Dugdale was innovative in his use of illustrations: not only in increasing the number, but also by introducing new page formats, such as the positioning of illustrations and text on the same page. From a book production viewpoint, this was a much more complex process: two different presses were needed to print the pages – a rolling press for the engraved plates of images and a familiar letter-press for the type (see Vander Meulen, ‘Sir William Dugdale and the making of books’, page 107). Type and image would have to be printed separately, often in different locations, leaving room for error: page 906 of the second volume of Worcester’s copy illustrates what could go wrong.

Upside-down illustration of tombs from the Church of Bermingham, ‘In the Ile on the South side of the Chancell’, page 906.

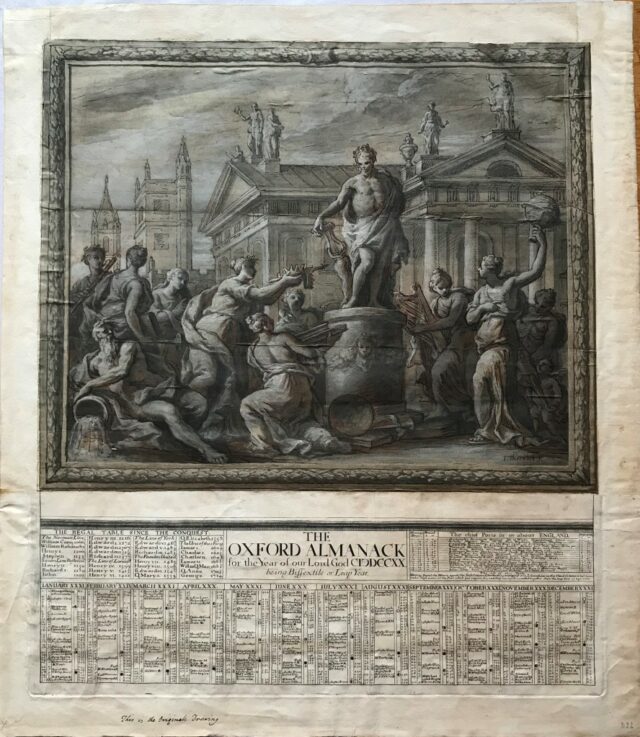

Most of the plates in Antiquities of Warwickshire are the work of Wenceslaus Hollar (1607-1677), the Bohemian printmaker who came to England in 1636 and spent the rest of his life here. One famous collector of Hollar’s works was A.W.N. Pugin (1812-1852), the architect, writer and designer. It is particularly pleasing, therefore, to find Pugin’s bookplate at the front of volume one and, indeed, information on both volumes can be found in the 1853 Sotheby and Wilkinson sale catalogue of Pugin’s library (reprinted in Watkin (ed.), Sale catalogues of libraries of eminent persons, volume 4: architects), where the second edition of Dugdale is listed as item 201, ‘a very fine copy in russia extra’ (i.e. bound in specially tanned cowhide with a rich smooth effect, and finished with lettering and decoration in the most elegant style). It was bought by the bookseller Toovey for £22.

Pugin’s personal bookplate

Pugin’s library reflected a ‘single-minded, almost fanatical devotion to a single theme: the religious and social life of pre-Reformation Europe’ (Watkin, Sale catalogues, page 240) – to which the Dugdale contributed, with its emphasis on genealogical histories, and its illustrations of monks’ habits (unfamiliar to seventeenth-century readers 100 years after the Dissolution of the Monasteries). In James Campbell’s library, whilst it can be classified among a broad group of works of early antiquarians, it nonetheless formed part of a much more eclectic collection, reflecting the wide range of interests of the man himself. Worcester College Library is honoured to have the opportunity to care for this collection in his memory.

Mark Bainbridge, Librarian

Bibliography

- Jenkins, H.M., ‘Dr. Thomas’s edition of Sir William Dugdale’s Antiquities of Warwickshire’ (Dugdale Society Occasional Papers, no.3; Oxford, 1931)

- Parry, G., ‘Dugdale, Sir William (1605-1686)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2004) [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/8186, accessed 25 November 2016]

- Parry, G., ‘The Antiquities of Warwickshire’, in Dyer, C. and C. Richardson (eds.), William Dugdale, historian, 1605-1686: his life, his writings and his county (Woodbridge, 2009)

- Roberts, M., Dugdale and Hollar: history illustrated (Newark and London, 2002)

- Vander Meulen, D., ‘Sir William Dugdale and the making of books’, in Roberts, Dugdale and Hollar, pages 105-111

- Watkin, D.J. (ed.), Sale catalogues of libraries of eminent persons, volume 4: architects (London, 1972)