Cromwell’s Citadels

27th September 2019

Cromwell’s Citadels

MS.155 – Scottish maps and plans from the Clarke Papers

The Clarke Papers have been the subject of two previous blog posts (see January 2016 and April 2019) and this month we delve into them once again to look at a series of maps and plans relating to the Cromwellian occupation of Scotland.

William Clarke (1623/4-1666) travelled to Scotland as part of Cromwell’s army in 1650. He had been secretary to the Council of Officers since 1647 and remained in Scotland as secretary, and eventually close advisor, to General Monck until the Restoration in 1660 (for more on William Clarke, see Frances Henderson, ‘Clarke, Sir William (1623/4-1666)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography). Clarke’s papers include many documents relating to the military administration in Scotland, including a handful of plans for the Protectorate citadels.

Following the invasion of Scotland in 1650, General Monck was left as acting commander-in-chief and tasked with controlling a population that was not uniformly pleased to be under the thumb of the Lord Protector. The government devised several systems to keep the Scots in line, one of which was to establish a series of garrisoned forts and citadels in strategic places throughout the country (C.H. Firth, Scotland and the Protectorate, pp. xxxvi – xxxix). Many of the smaller garrisons were established in existing forts and castles, which were repaired and fortified for the purpose (Christopher Fleet et al., Scotland: Mapping the Nation, p. 38; A.A. Tait, ‘The Protectorate Citadels of Scotland’, p. 9). One of the plans in our collections is an example of this.

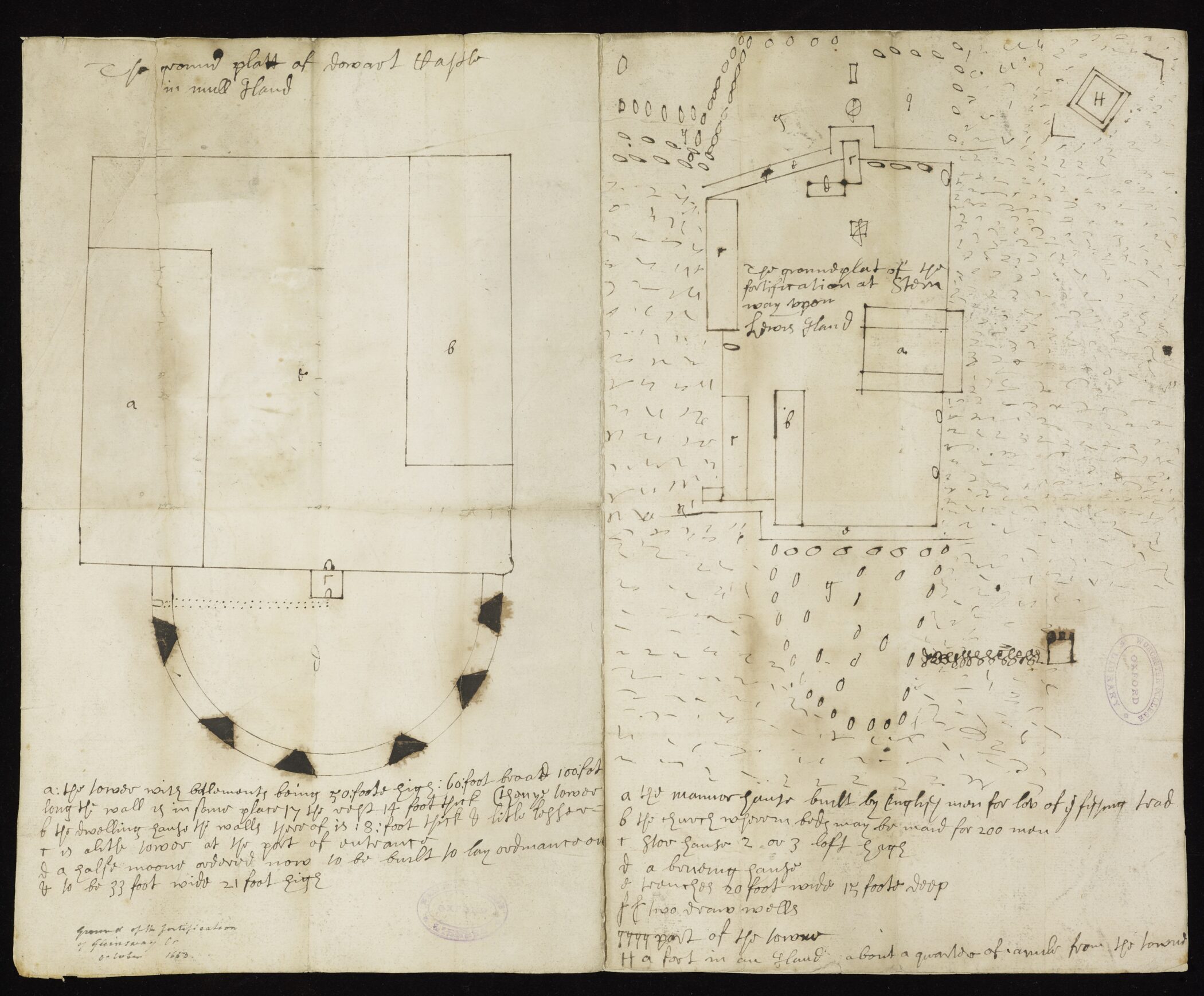

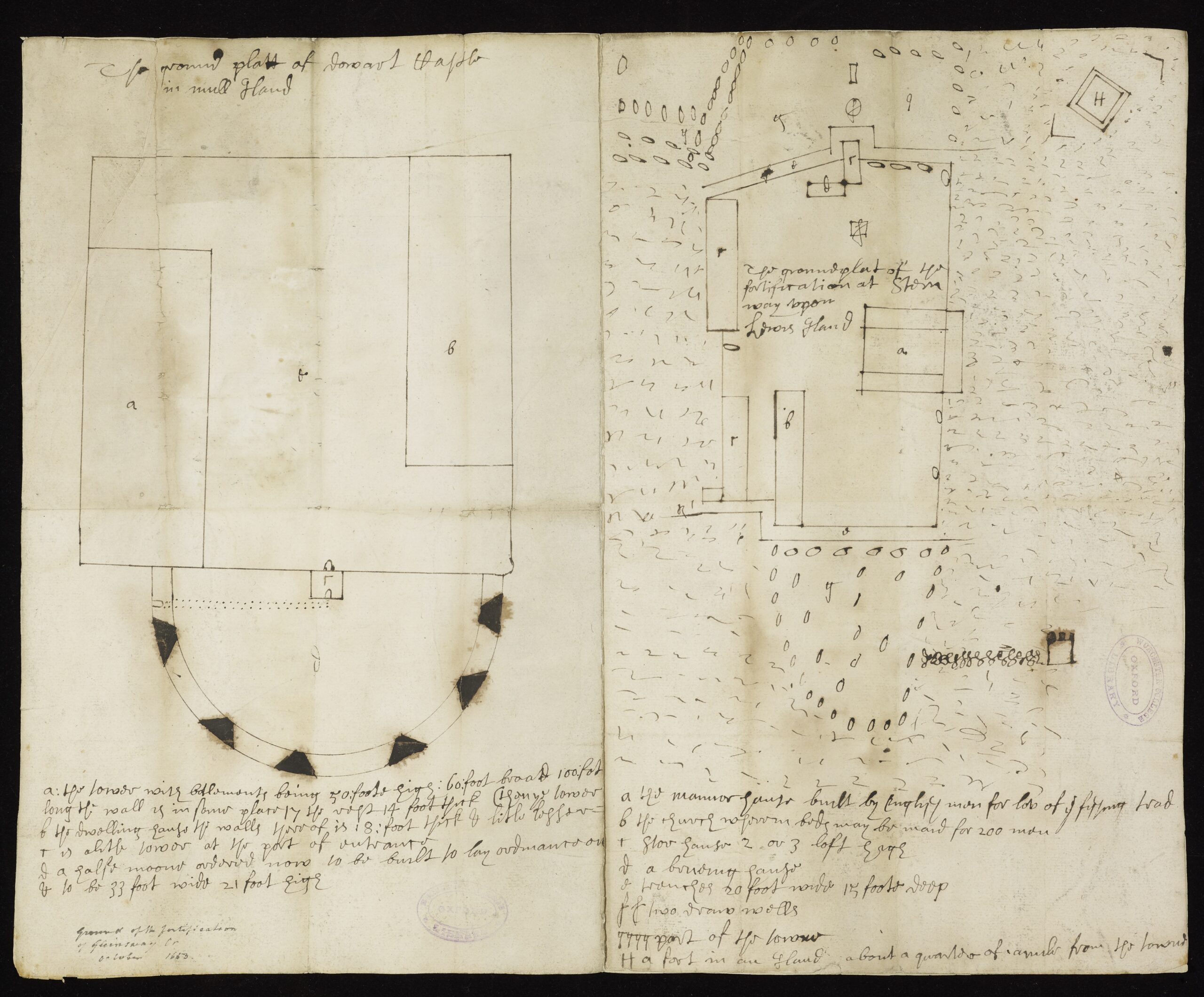

The ground platt of Dowart Castle in Mull Island, 1653

This plan shows designs for improvements to the fortifications of Duart Castle on the Isle of Mull on one side, and the building of new fortifications in Stornoway on the Isle of Lewis on the other. Duart Castle had been the property of the Royalist MacLeans of Duart until Sir Hector MacLean was killed at the Battle of Inverkeithing in 1651 and the castle was taken by Cromwell in 1653 (Carolyn Anderson and Christopher Fleet, Scotland: Defending the Nation: Mapping the Military Landscape, p. 44). The plans above propose the addition of a half-moon battery to one side of the castle, but there is no evidence that this was built (Anderson/Fleet, Defending the Nation, p. 44). The fortifications in Stornoway shown on the right side were built following a rebellious outburst by the Earl of Seaforth in 1653 (Anderson/Fleet, Defending the Nation, p. 44). According to the notes at the bottom of the plan, the fort included store-houses, a brewing-house, and two wells, and encompassed an old church (which became a dormitory) and a ‘manor-house built by Englishmen for love of the fishing trade’. The fort seems to have had a substantial impact on the town; many of the soldiers stationed there lived in the town and stone was taken from existing buildings to build it as there was a shortage of timber (Anderson/Fleet, Defending the Nation, pp. 44-45).

Description of the forts at Inverlouchee (Inverlochy), 1656

A more substantial fort for which a plan has survived is that of Inverlochy. Inverlochy was strategically significant for controlling the Highlands and a garrisoned fort was established there in 1654 (Firth, Scotland and the Protectorate, p. xl). However, according to Firth and Tait, it was a notoriously unpopular posting with soldiers, thanks to its remoteness, scarcity of resources, and terrible weather (Firth, Scotland and the Protectorate, p. xl; Tait, ‘The Protectorate Citadels’, p. 10).

In addition to the network for smaller garrisoned forts, the government built four substantial citadels to impress upon the locals the power of the Protectorate – at Ayr, Inverness, Leith, and Perth. Work began on the citadels between 1652 and 1656 but it seems likely that none of them were ever fully completed (Tait, ‘The Protectorate Citadels’, p. 12). Plans for those at Inverness and Ayr survive in the Clarke Papers.

![MS.155 (4) - hand drawn plan of the Fort at I[nverness], undated](https://www.worc.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/ms.155-4-scaled.jpg)

MS.155 (4) – Fort at [Inverness], undated

MS.155 (5) – Fort at Inverness, undated

There are two plans for the citadel at Inverness here in Worcester, one which was accepted (MS.155 (5)) and one which was rejected for ‘being made too large, and the tymes no being afforded to demand itt’ (MS.155 (4)) (Tait, ‘The Protectorate Citadels’, p. 13). But based on contemporary descriptions the citadel was still a grand structure. The minister of Kirkhill describes it as

‘five-cornered with bastions, with a wide trench that an ordinary barque might sail in at full tide ; the breast-work three storeys, built all of hewn stone limed within… and on the north a great entry or gate called the Port, with a strong drawbridge of oak called the Blue Bridge, and a stately structure over the gate, well cut with the Commonwealth’s arms and the motto “Togam tuentur arma”… [there] are lower storeys for ammunition, timber, lodgings for manufactories, stablings, provision and brewing houses, and a great long tavern with all manner of wines, viands, beer, ale and cider… so that the whole regiment was accommodated within these walls.’ (quoted in Firth, Scotland and the Protectorate, pp. xlv-xlvi)

The minister also shows some of the possible positive impacts the citadel could have on the town, saying ‘they brought such store of all wares and conveniences to Inverness that English cloth was sold near as cheap here as in England…’ (quoted in Firth, Scotland and the Protectorate, p. xlvi).

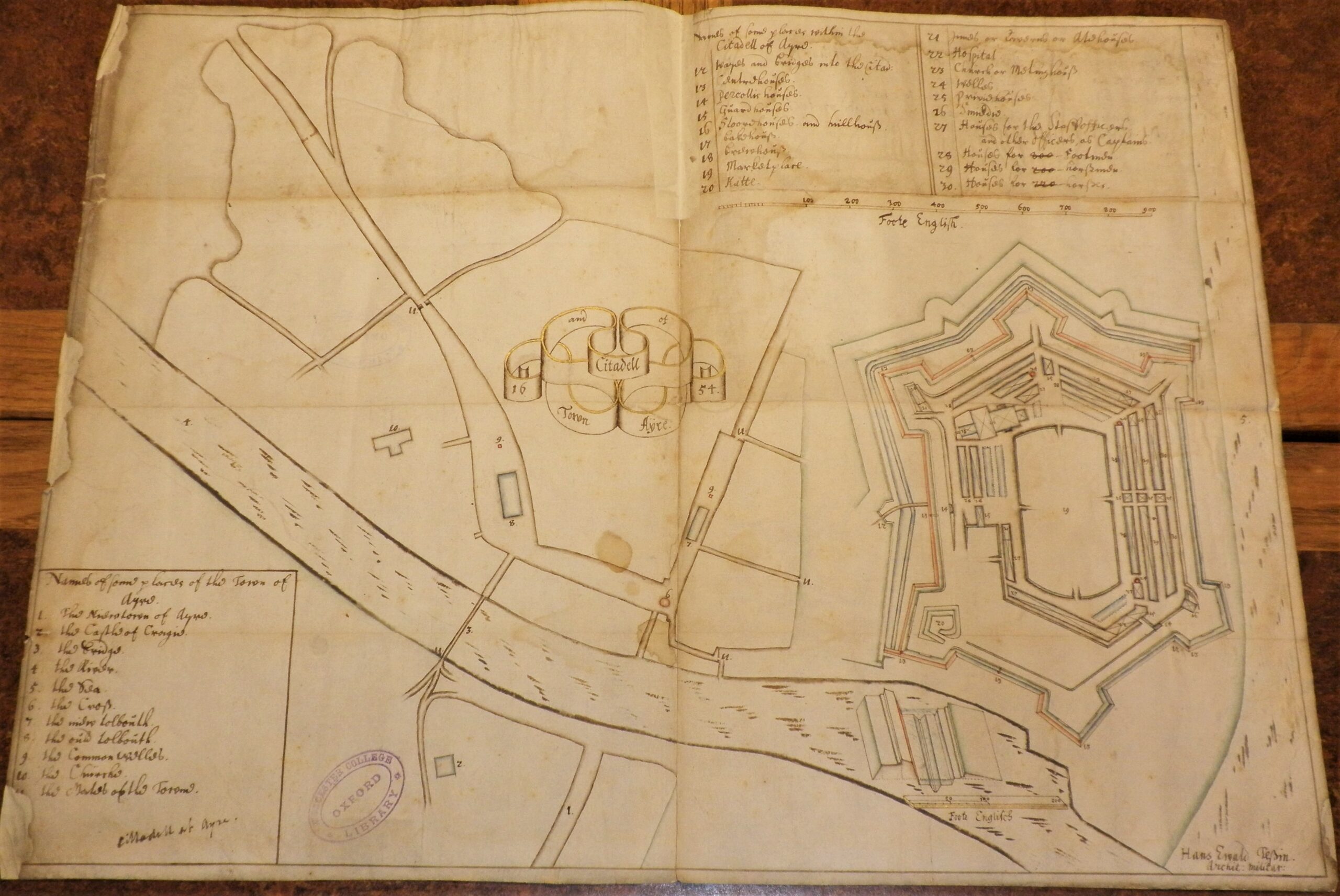

Hans Ewald Tessin, Town and Citadell of Ayre, 1654

The plan for the citadel at Ayr is the only one of those in Worcester which has a known creator – Hans Ewald Tessin. Tessin was a Swedish military architect who came to Scotland in the 1650s to work for the English army (‘Tessin, Hans Ewald [SSNE 6600]’, The Scotland, Scandinavia and Northern European Biographical Database (SSNE)). Fleet et al. describe the period 1500-1700 as an era of military revolution, during which the size, complexity, and artillery power of armies increased. Among other things, this resulted in a need for new types of fortifications, which fuelled the demand for specialist military engineers and architects (Fleet et al., Mapping the Nation, p. 75). According to Anderson and Fleet, military engineers were an increasingly professionalised workforce with an international outlook who were willing to work for different states (Anderson/Fleet, Defending the Nation, p. 15). Tessin was an example of this – following his work in Scotland for the Protectorate, he worked for Charles II in Dunkirk (‘Tessin’, SSNE).

The cost of the citadels was enormous. Firth estimates the citadel at Inverness cost £50,000 – £80,000 to build, while Fleet suggests that each citadel may have cost more than £100,000 (Firth, Scotland and the Protectorate, p. xliv; Fleet et al., Mapping the Nation, p. 76). Throughout the Clarke Papers there are requests to London for extra funds to complete and maintain fortifications in Scotland (Firth, Scotland and the Protectorate, pp. xliii-l; Tait, ‘The Protectorate Citadels’, p. 15). And yet, for all their might and expense, none of the citadels have survived. Indeed it was because of their might that they were destroyed. Tait describes the citadels as the ‘incarnation of the political propaganda of the Protectorate government’ and as such, they were deliberately demolished at the Restoration (Tait, ‘The Protectorate Citadels’, pp. 15, 10). The plans preserved here in the Clarke papers provide some of the only visual evidence of their existence.

Renée Prud’Homme, Assistant Librarian

Bibliography

- Anderson, Carolyn, and Christopher Fleet, Scotland: Defending the Nation: Mapping the Military Landscape (Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2018)

- Charting the Nation: maps of Scotland and associated archives 1550 – 1740, Edinburgh University Library (http://www.chartingthenation.lib.ed.ac.uk/, last updated 9/9/2014)

- Firth, C.H., Scotland and the Protectorate. Scottish History Society, vol. XXXI (Edinburgh, 1899)

- Fleet, Christopher, Margaret Wilkes, and Charles W.J. Withers, Scotland: Mapping the Nation (Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2011)

- Henderson, Frances, ‘Clarke, Sir William (1623/4-1666)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/5536, 3 January 2008)

- Tait, A.A., ‘The Protectorate Citadels of Scotland’, Architectural History Vol. 8 (1965), pp. 9-24

- ‘Tessin, Hans Ewald [SSNE 6600]’, The Scotland, Scandinavia and Northern European Biographical Database (SSNE), University of St. Andrews, 2004 (https://www.st-andrews.ac.uk/history/ssne/)