Bold, Soft, Swift and Sure: drawings by Inigo Jones in the collections of Worcester College Library

28th February 2019

Bold, Soft, Swift and Sure: drawings by Inigo Jones in the collections of Worcester College Library

For Anthony Van Dyck, Inigo Jones was the only Englishman of the 17th century who could draw. John Webb, Jones’ apprentice, reports Van Dyck’s judgement on Inigo Jones in A Vindication of Stone-Heng restored (1665, page 11):

‘in designing with his Pen (as Sir Anthony Vandike used to say) not to be equalled by whatever great Master in his Time, for Boldness, Softness, Swiftness, and Sureness of his Touches’.

Comments such as ‘freshness and vitality’ (Higgott, ‘Style and technique’, page 25), ‘superior freedom’ (Colvin, Royal buildings, page 13), ‘beautifully and freely drawn’ (Harris, The Palladians, page 13), used by modern scholars to describe Jones’ drawings, echo the views of Van Dyck on Jones’ draughtsmanship. Webb’s hand, by contrast, is described as ‘always competent and often attractive, but [Webb’s drawings] lack the artistry and flair of those of Jones’ (Bold, John Webb, page 10). Damned with faint praise as ‘academic’ (Harris, The Palladians, page 144), Webb’s ‘laborious competence’ (Colvin, Royal buildings, page 16) and ‘painstaking delineation’ (Bold, page 10) are noted, as is his ‘tentative approach to figure drawing’ (Bold, page 62).

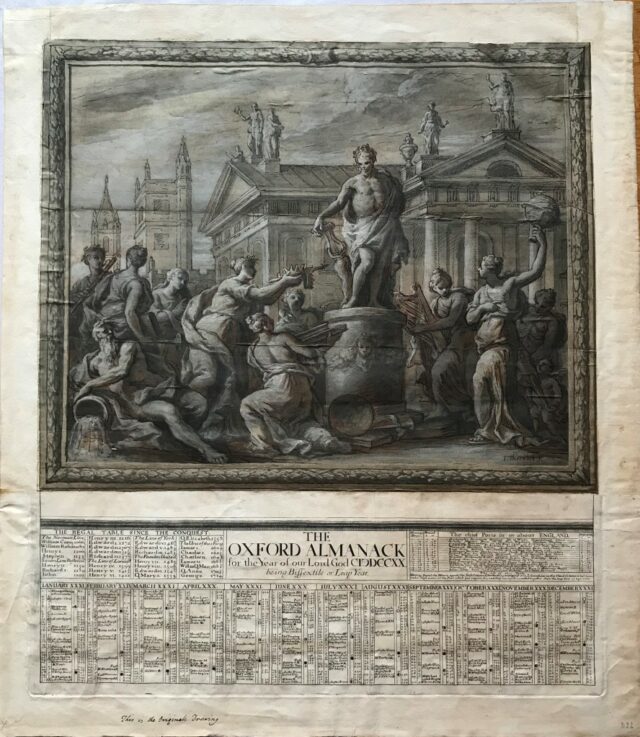

Wenceslaus Hollar, portrait engraving of Inigo Jones, after Anthony Van Dyck

These differences are useful to note given the collections of Worcester College Library. There are 249 catalogue entries in Harris and Tait’s Catalogue of the drawings by Inigo Jones, John Webb & Isaac de Caus at Worcester College Oxford. Of these, 19 are designs ascribed to Isaac de Caus (1589/90-1648, garden designer and architect), 143 to John Webb, and a further 71 are classified as ‘Designs by Inigo Jones’, although only 17 are now considered as drawn by his own hand; the majority are in the hand of John Webb or other unknown individuals. (Excluded here are 110 mounted fragments, all figurative, and catalogued by Harris and Tait under one entry, number 72.) Our aim here is to follow the development of Jones’ drawing style through the 17 architectural drawings in the Worcester collection that are currently accepted as being in Jones’ own hand. How does one identify a drawing by Inigo Jones?

The essential guide to Jones’s style and technique is Dr Gordon Higgott, cataloguer of his complete architectural drawings: the following scheme relies on the much fuller account given by Higgott in his and John Harris’ Inigo Jones: complete architectural drawings; readers are advised to consult that for more detail.

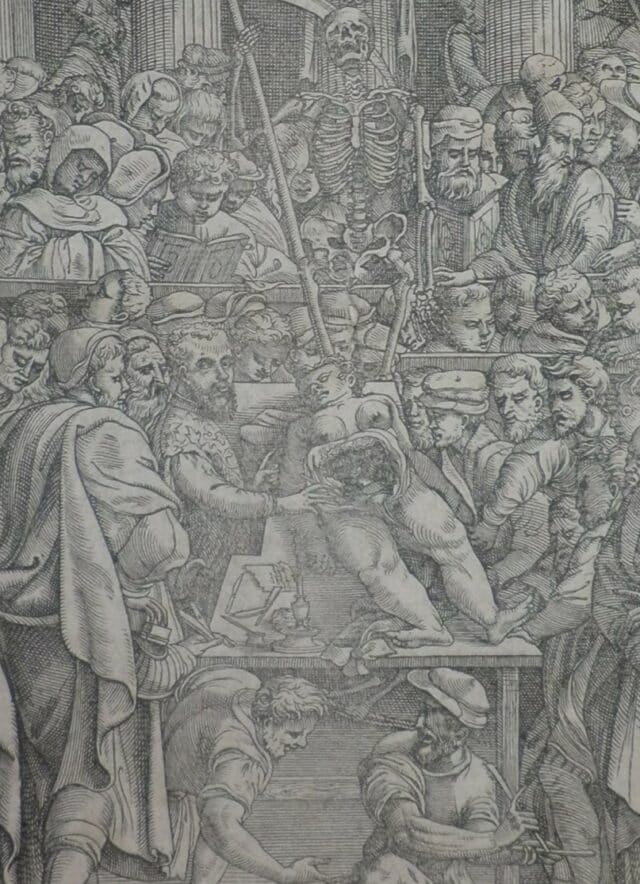

Jones began his career as a stage designer, producing excellent figurative drawings for the masques of Ben Jonson and others performed at the Stuart Court. His earliest architectural drawings can be dated to about 1608 (Harris, The Palladians, page 12) and in his earliest period of architectural design Jones’ drawing was still ‘painterly’, with ‘very tentative’ outlines, ‘the trembling straight lines betraying Jones’ inexperience in the discipline of architectural drawing’ (Higgott, ‘Style and technique’, page 25). Two early examples can be found in the Worcester collections: a design for the arcaded front of the New Exchange in the Strand (Harris & Tait (henceforth H&T) 9) and a design for the central tower of the old St Paul’s Cathedral (H&T 13).

H&T 9: Elevation for the New Exchange in the Strand

H&T 13: Design for the central tower of the old St Paul’s Cathedral, London

After his ‘Second Italian Journey’ in 1613-1614, on which he both acquired drawings by Palladio and met Vincenzo Scamozzi (1548-1616, the Italian ‘successor’ to Palladio), Jones’ technique became more architectural: he now used rulers to achieve straight outlines; the wash was evenly graded; and drawings were underscored first. At Worcester, a drawing in Jones’s own hand from this period is H&T 12, a side elevation for the Queen’s House at Greenwich, in pen, pencil and ink.

H&T 12: Preliminary side elevation for the Queen’s House, Greenwich

Although making improvements in terms of the provision of architectural information, Jones was still somewhat heavy handed and less tidy at this period. But he was now working in the idiom of architectural drawing – i.e. conveying information in plan, elevation and section, following the conventions of orthogonal drawing, as described by Leon Battista Alberti:

‘Between the drawing of a painter and that of an architect there is the difference that the former seeks to give the appearance of relief through shadow and foreshortened lines and angles. The architect rejects shading and gets projection from the ground plan. The disposition and image of the façade and side elevations he shows on different [sheets] with fixed lines and true angles as one who does not intend to have his plans seen as they appear [to the eye] but in specific and consistent measurements.’ (Leon Battista Alberti, De re aedificatoria, 2.1; translation by J. Ackermann, ‘The origins of architectural drawing in the Middle Ages and Renaissance’, page 2)

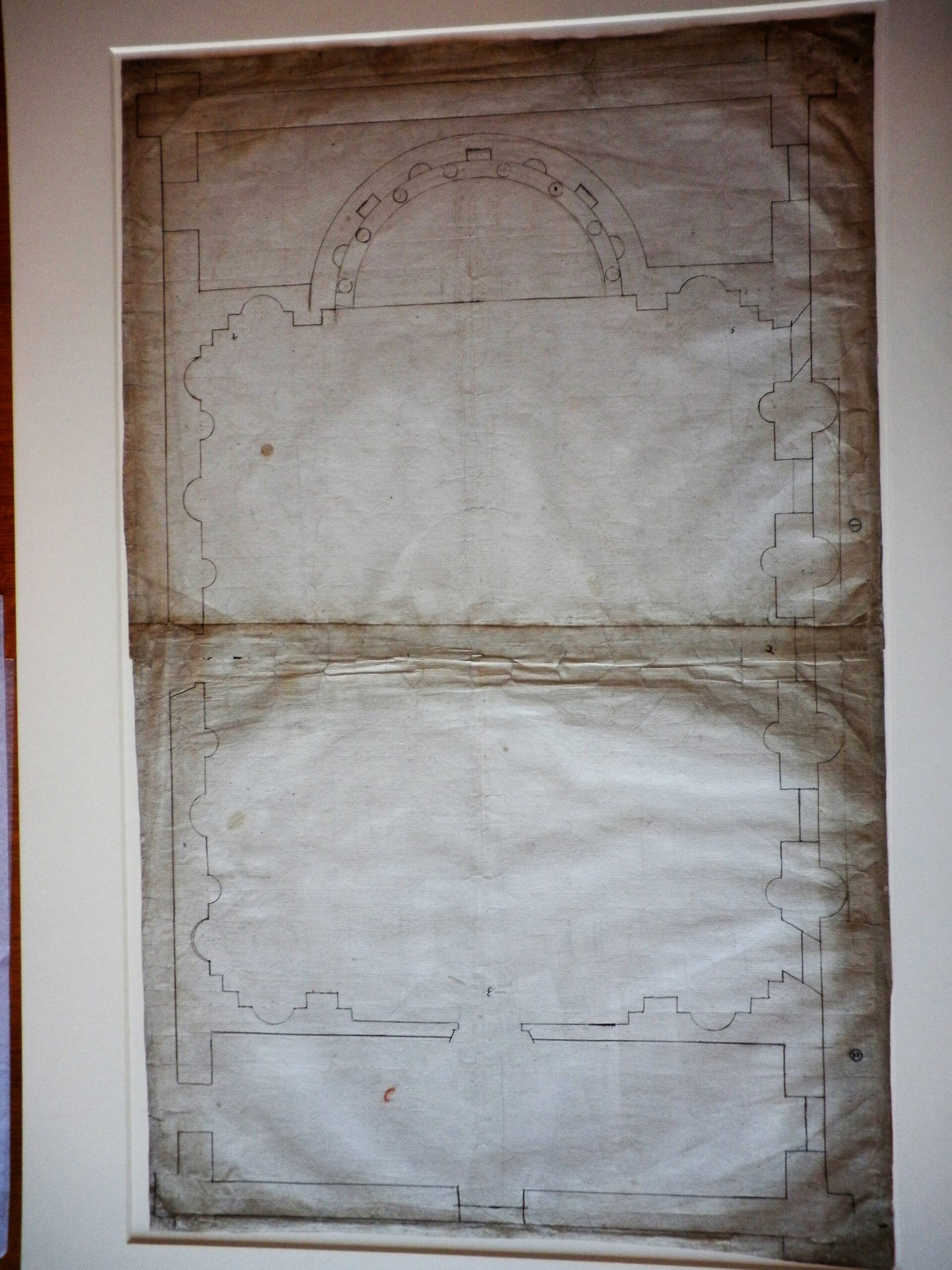

H&T 20 and 21 (originally catalogued separately, but after conservation now joined on one sheet), the ground plan of the Star Chamber, dated to 1617, show an early orthogonal plan by Jones.

H&T 20 and 21: Ground plan for a new Star Chamber

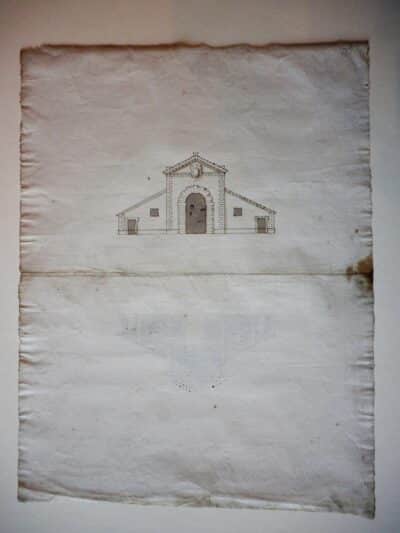

1620-1630 is the third period of Jones’ drawing style and technique. As Higgott writes, ‘Drawings in this decade have firmer and cleaner pen outlines, a tidier scoring technique, and lighter, more smoothly handled wash than in the period from 1616-1619’ (Higgott, ‘Style and technique’, page 26). Worcester has five drawings dating from this period: from the early 1620s comes a design for a stable, with elevation on the recto of the sheet, its elevation pricked through to provide the outline of the section drawn on the verso of the folded paper.

- H&T 57 recto: Elevation for a stable, possibly at Newmarket Palace

To c.1622-1623 dates the most immediately striking of the College’s Jones drawings: a beautiful colour design (H&T 3) for a coffered ceiling, perhaps for the Marquis of Buckingham (one of only two colour-washed Jones designs – Harris and Higgott, page 178).

H&T 3: Design for a ceiling, possibly for the Marquis of Buckingham

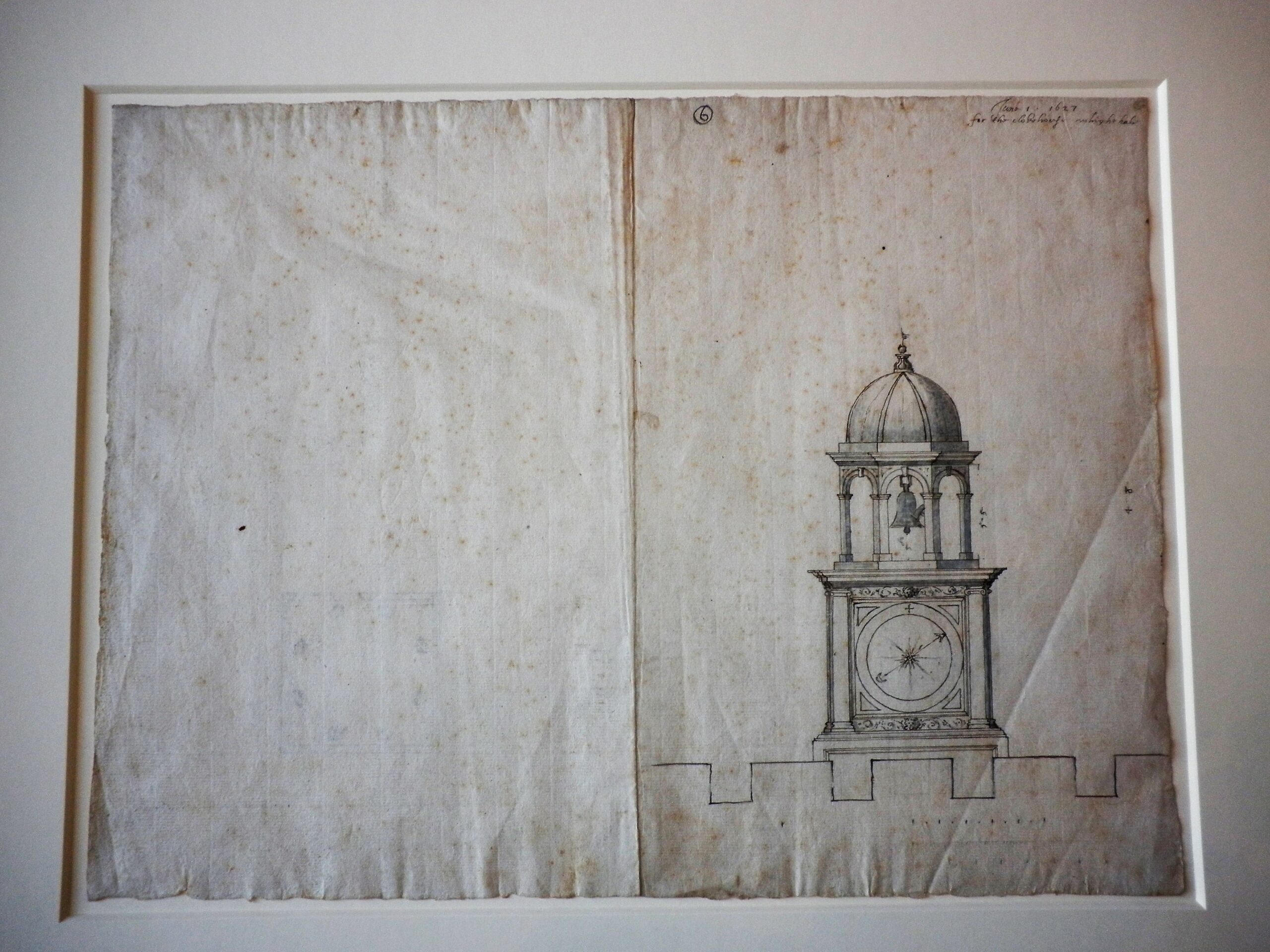

The 1620s Jones drawings at Worcester are completed by two designs (H&T 25 and 26) from 1625 for the catafalque of James VI and I and a 1627 design for a Clock House turret at Whitehall (H&T 27).

The catafalque drawings are two finished designs for a prestige project, although in general from the mid-1620s Jones was less concerned with presentation drawings, and his draughtsmanship can be found more in preliminary drawings, sketching out new designs for later working up. (It can be noted that John Webb entered Jones’ office in 1628 and he, together with other assistants, could perhaps be relied upon to finish fairer copies for clients.) This change in practice was accompanied by his use of poorer quality paper – grainy and greyish in colour, always with watermarks of variants on a water-pot motif (Higgott, ‘Style and technique’, page 27) – the type of paper on which is found H&T 27, the design for the Whitehall Clock House turret.

H&T 27: The turret of a clock house, Whitehall Palace

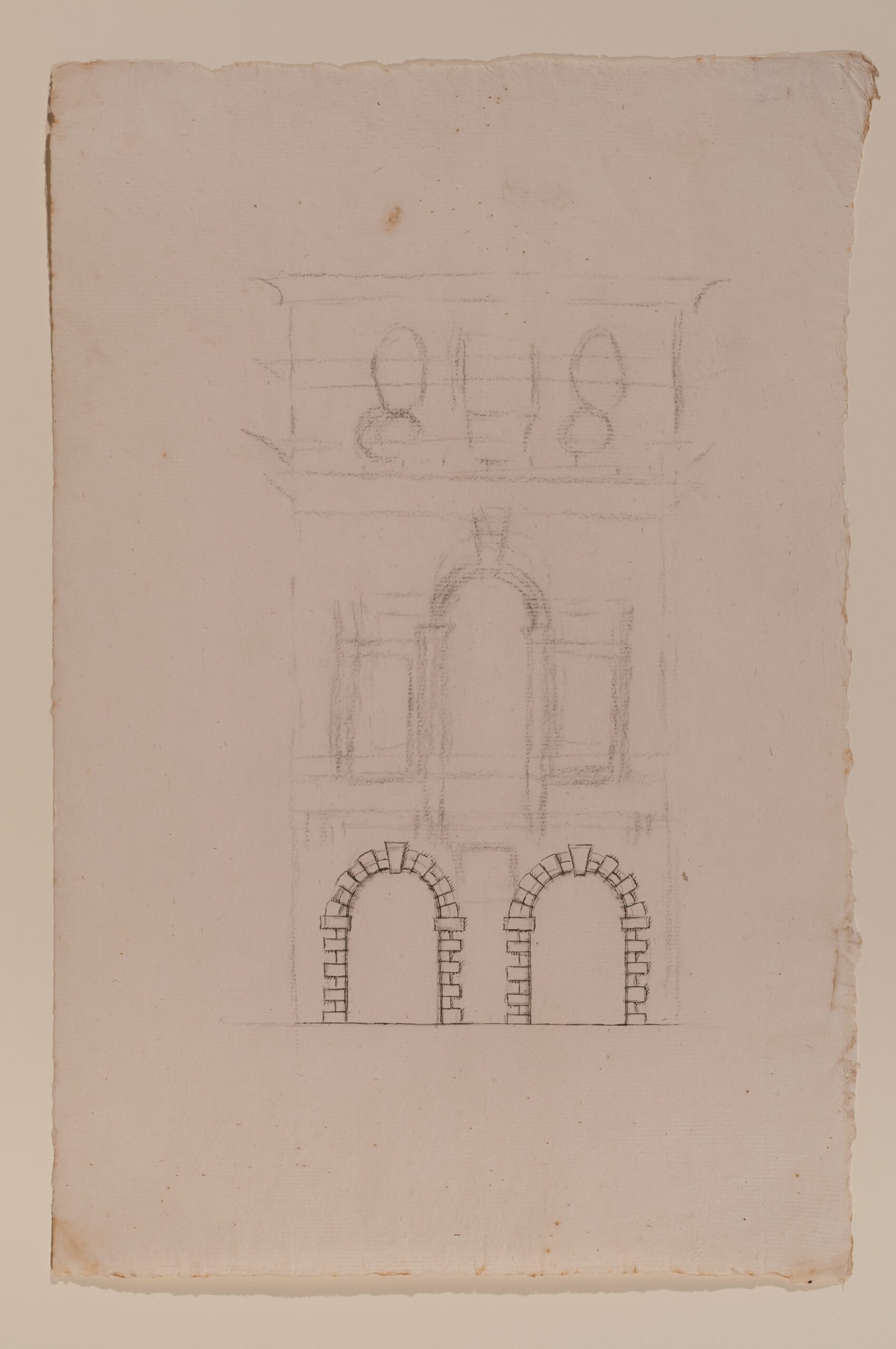

We should note that from the mid-1620s onwards, ‘graphite and black chalk superseded the scorer as [Jones’] main under-drawing techniques’ (Higgott, ‘Style and technique’, page 28). Black chalk and graphite under-drawing can easily be seen in H&T 70, a sketch for a town façade dated to 1630.

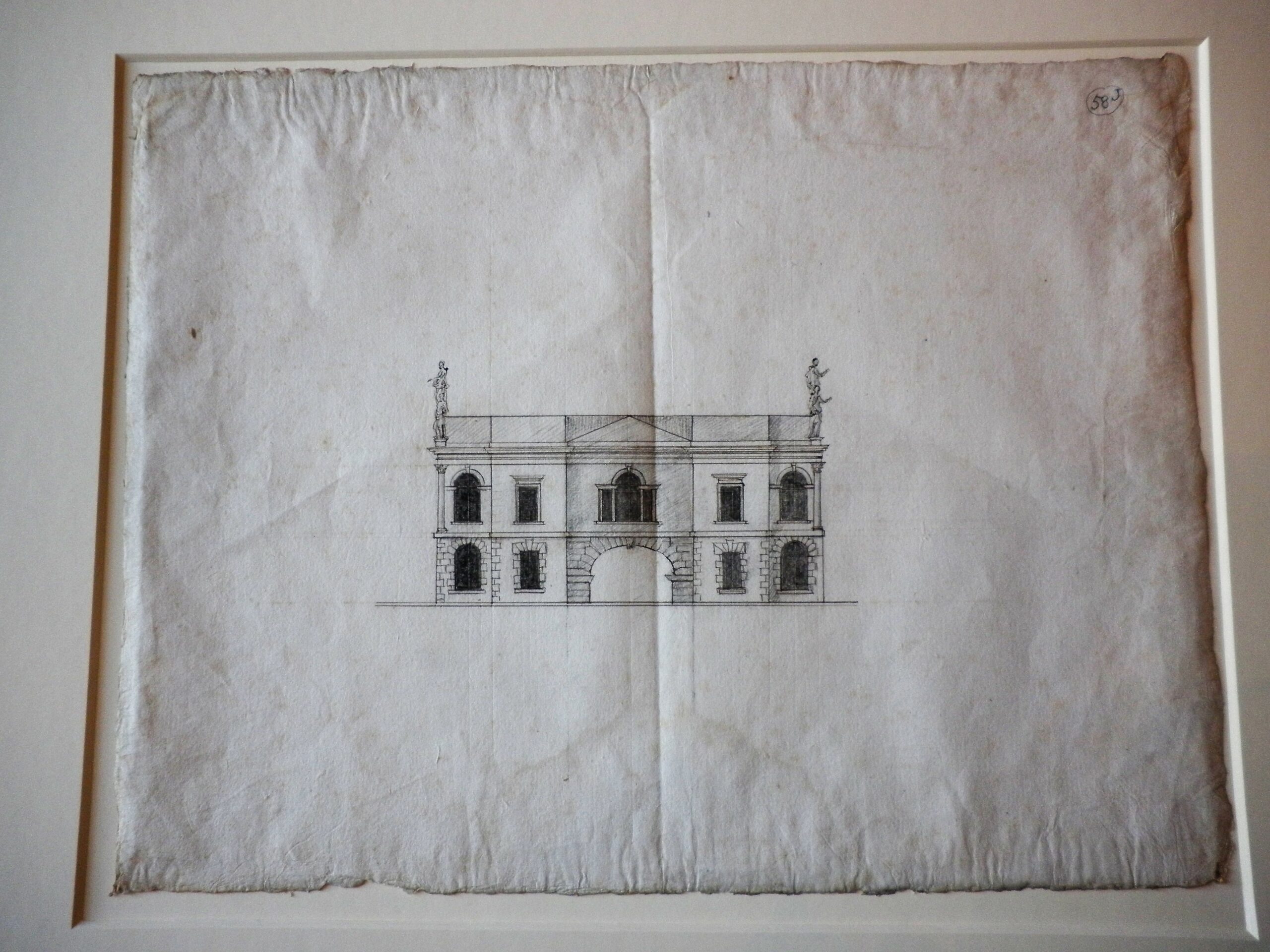

H&T 70: Design for a town facade

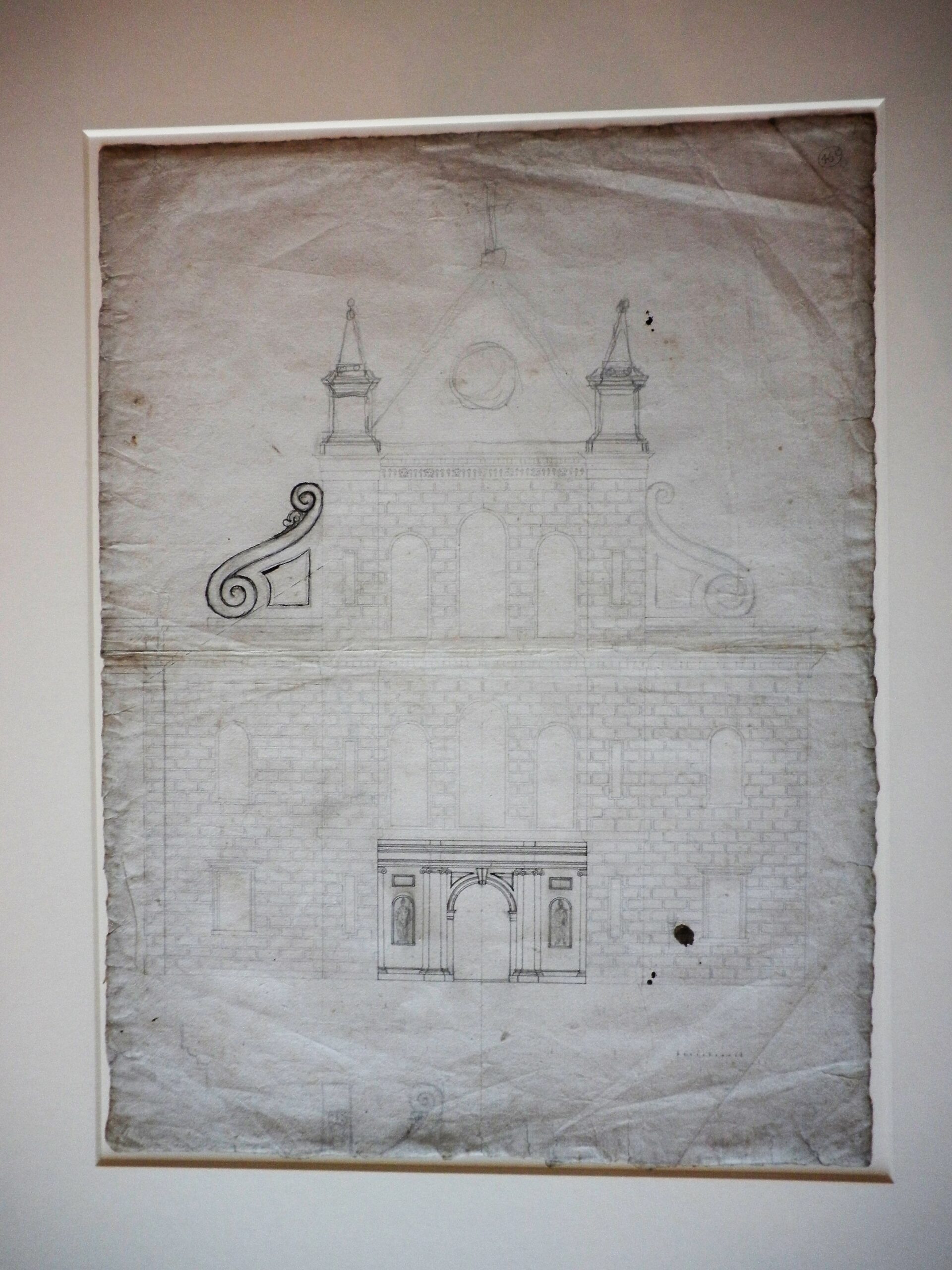

The 1630s were perhaps the zenith of Jones’ architectural drawing style. The earliest Worcester drawing from that decade is a sketch of the west front of St Paul’s (H&T 14).

H&T 14: The north transept front of St Paul’s Cathedral, London

H&T 14: The north transept front of St Paul’s Cathedral, London

As a sketch, this St Paul’s drawing is not in agreement with the dominant style of Jones’ 1630s draughtsmanship, which was characterised by thick, dark outlines, with, as the decade progressed, regular pen (not wash) shading applied to clearly drawn lines (cf. Higgott, ‘Style and technique’, page 29). Fully ruled and precisely joined outlines can be seen in two related designs (H&T 66 and 67) for a tempietto or cupola.

Jones’ assured style of drawing is also seen very clearly in four drawings for houses (H&T 6, 7, 8, and 68), all dated to c.1638, and two of which (H&T 6 and 8) have been associated with a project for Lord Maltravers in Lothbury, London.

With their clear and fully ruled outlines, very accurate and uniform penmanship (see, for example, the thin iron posts of the balcony in H&T 68), these small-scale designs (contrasting with the large-scale drawings of Jones’ early architectural career) show a draughtsman fully at home in his medium.

Note that H&T 6 and 7 are, with H&T 3 and 27, the only four drawings in Worcester by Jones that also have his handwriting on them (for an analysis of Jones’ handwriting, see Newman, ‘Inigo Jones’ architectural education before 1614’). Although this is no certain proof that a drawing is by Jones (he signed or commented upon drawings made, for example, by Webb), combining it with the style and technique of the drawing does strengthen the case for Jones’ authorship. That case, however, is based primarily on analysis of the drawing:

- What materials were used? Pen, ink, wash, graphite or chalk? What type of paper?

- What techniques were applied? What method of shading (wash or folding)? How was the drawing underscored?

- And how skilled was the draughtsman in handling his instruments? Here, one is concerned with width of line, the joining of outlines, and the firmness of details.

All of this needs to be underpinned, however, by familiarity with Jones’ whole body of work, known primarily through drawings housed in the collections of the Royal Institute of British Architects, the Ashmolean Museum, Chatsworth House and at Worcester College, Oxford.

Mark Bainbridge, Librarian

Bibliography

- Ackerman, J. S., ‘The origins of architectural drawing in the Middle Ages and Renaissance’, in Ackerman, Origins, imitations, conventions: representations in the visual arts (Cambridge, Mass.; London: MIT Press, 2002)

- Colvin, H., Royal buildings (Feltham: Country Life Books, 1968)

- Harris, J. and A. A. Tait, Catalogue of the drawings by Inigo Jones, John Webb, and Isaac de Caus at Worcester College Oxford (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1979)

- Harris, J., The Palladians (London: Trefoil Books, 1981)

- Harris, J. and G. Higgott, Inigo Jones: complete architectural drawings (London: P. Wilson for A. Zwemmer in association with the Drawing Center, New York, 1989)

- Higgott, G., ‘Style and technique’, in Harris and Higgott, Inigo Jones: complete architectural drawings

- Newman, J., ‘Inigo Jones’ architectural education before 1614’, Architectural History, volume 35 (1992), pages 18-50