A Book of Ice and Fire

29th August 2017

A Book of Ice and Fire

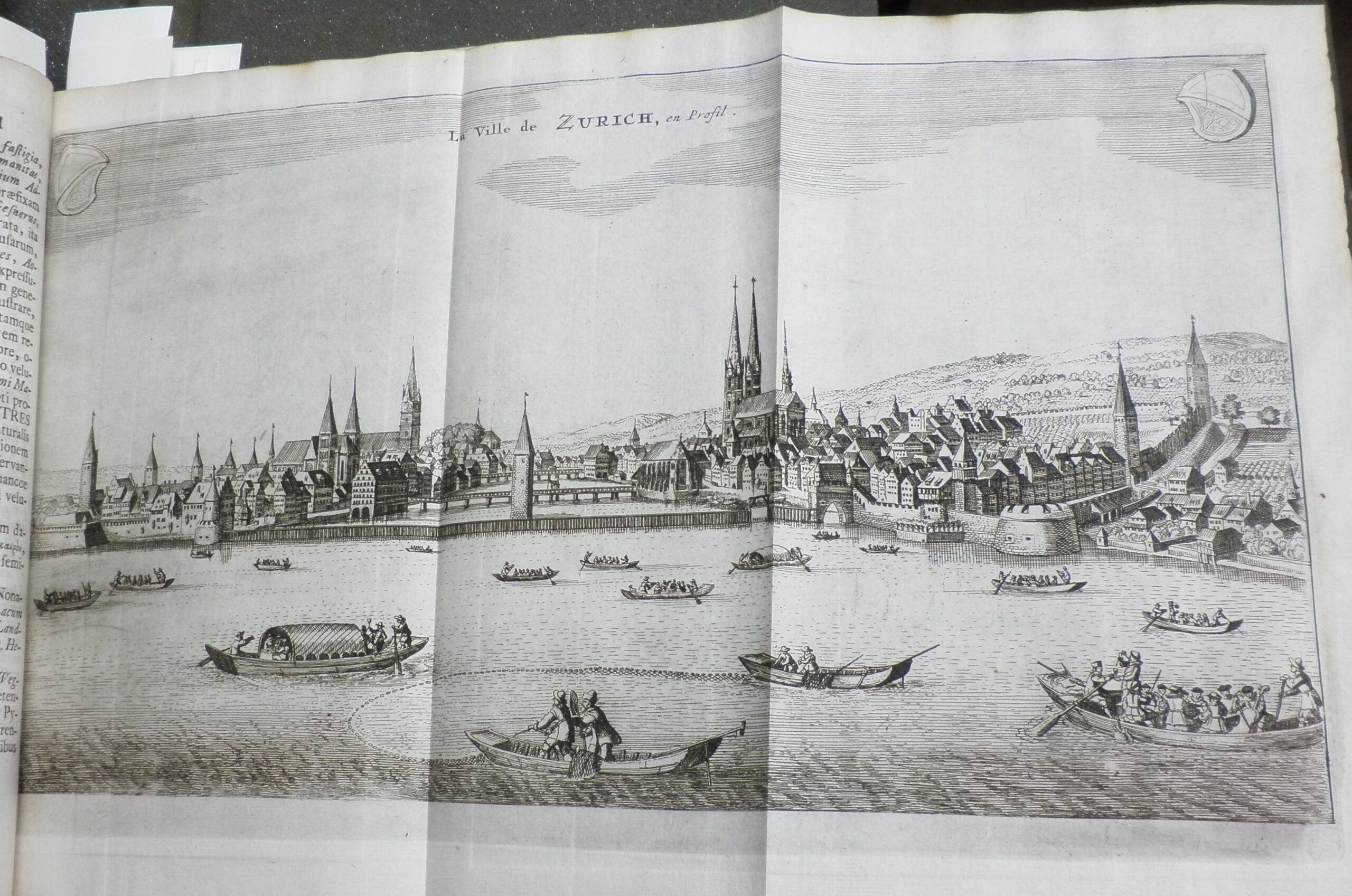

Ouresiphoites Helveticus, sive Itinera per Helvetiae alpinas regiones… / plurimis tabulis aeneis illustrata a Johanne Jacobo Scheuchzero.

Lugduni Batavorum : Typis ac sumptibus Petri Vander Aa., MDCCXXIII [1723].

[22], 635, [53] pages, [121] leaves of plates; quarto.

In August the College becomes rather quiet as everyone leaves for vacations, so in the Library as we sit down to write this month’s blog post our thoughts too turn to travel. We plan to make ‘August Atlases’ an annual event (see last August’s post), and although not strictly an atlas, this month’s volume includes several maps and plans among its rich illustrations. The Ouresiphoites Helveticus is an account of nine journeys through the Swiss Alps made by the Swiss scholar Johann Scheuchzer between 1702 and 1711.

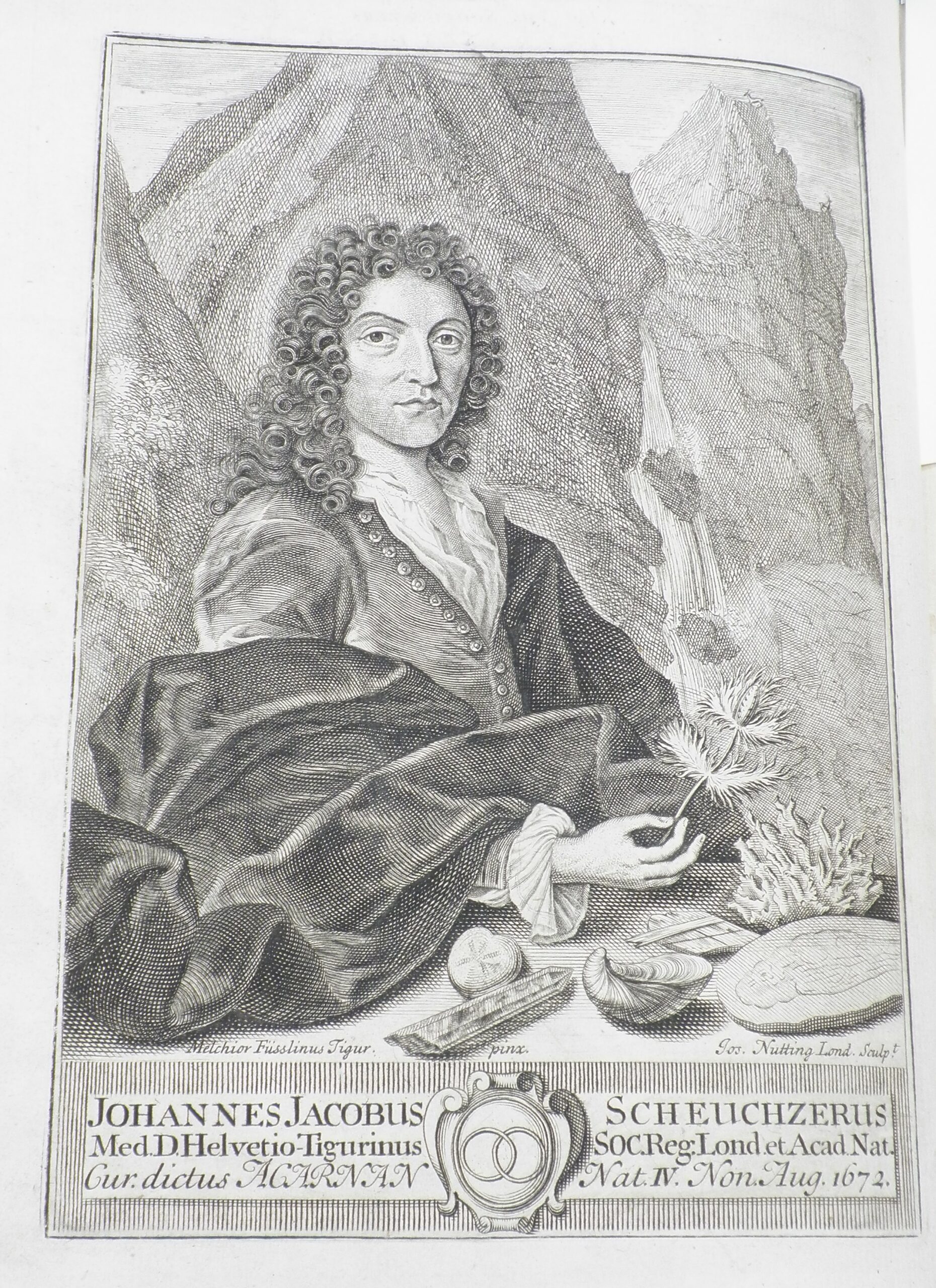

Johann Jakob Scheuchzer (1672-1733)

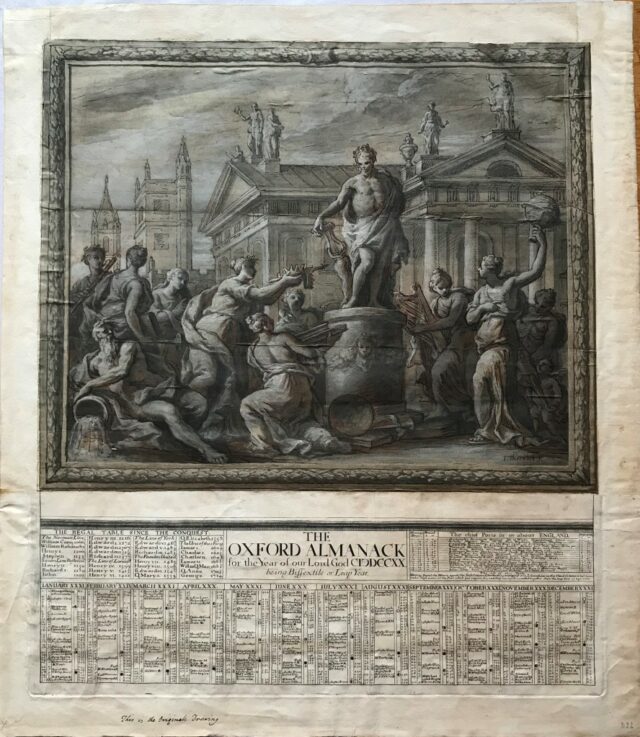

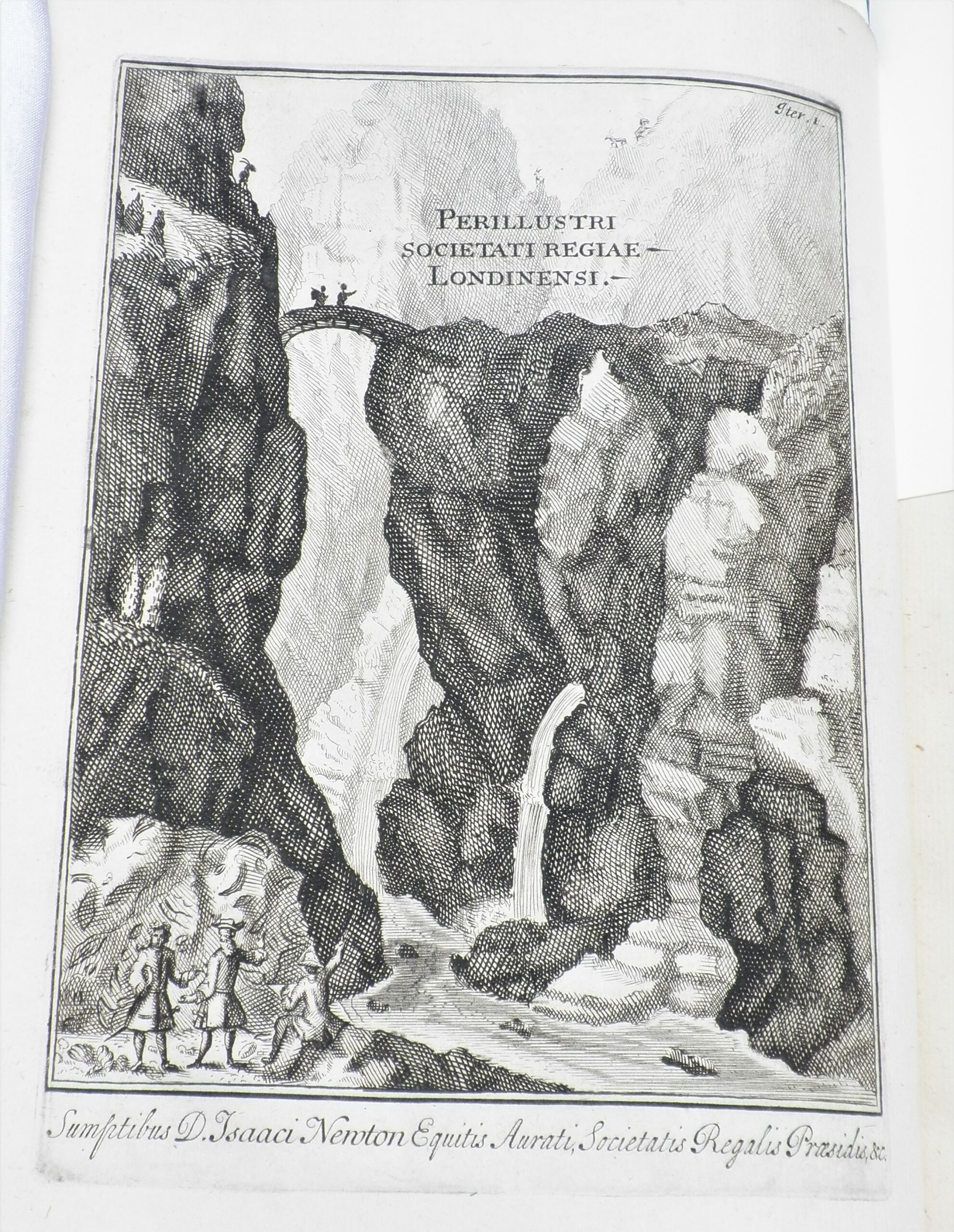

The volume includes and expands on his first three journeys (1702, 1703, and 1704), originally published in London in 1708 at the expense of the Royal Society, with plates (included in this edition) subscribed for by Fellows of that Society. Indeed, Scheuchzer could boast that the frontispiece was published under the imprimatur of the then president of the Society, Sir Isaac Newton. Other Fellows who paid for plates include the physician and collector Sir Hans Sloane (1660-1753), the natural historian and antiquary John Woodward (1665/1668-1728), Henry Aldrich (1648-1710), Dean of Christ Church (see the blog post for March 2017) and the botanist and Hortus Praefectus of Oxford’s Botanic Garden, Jacob Bobart the younger (1641-1719).

Frontispiece sponsored by Sir Isaac Newton.

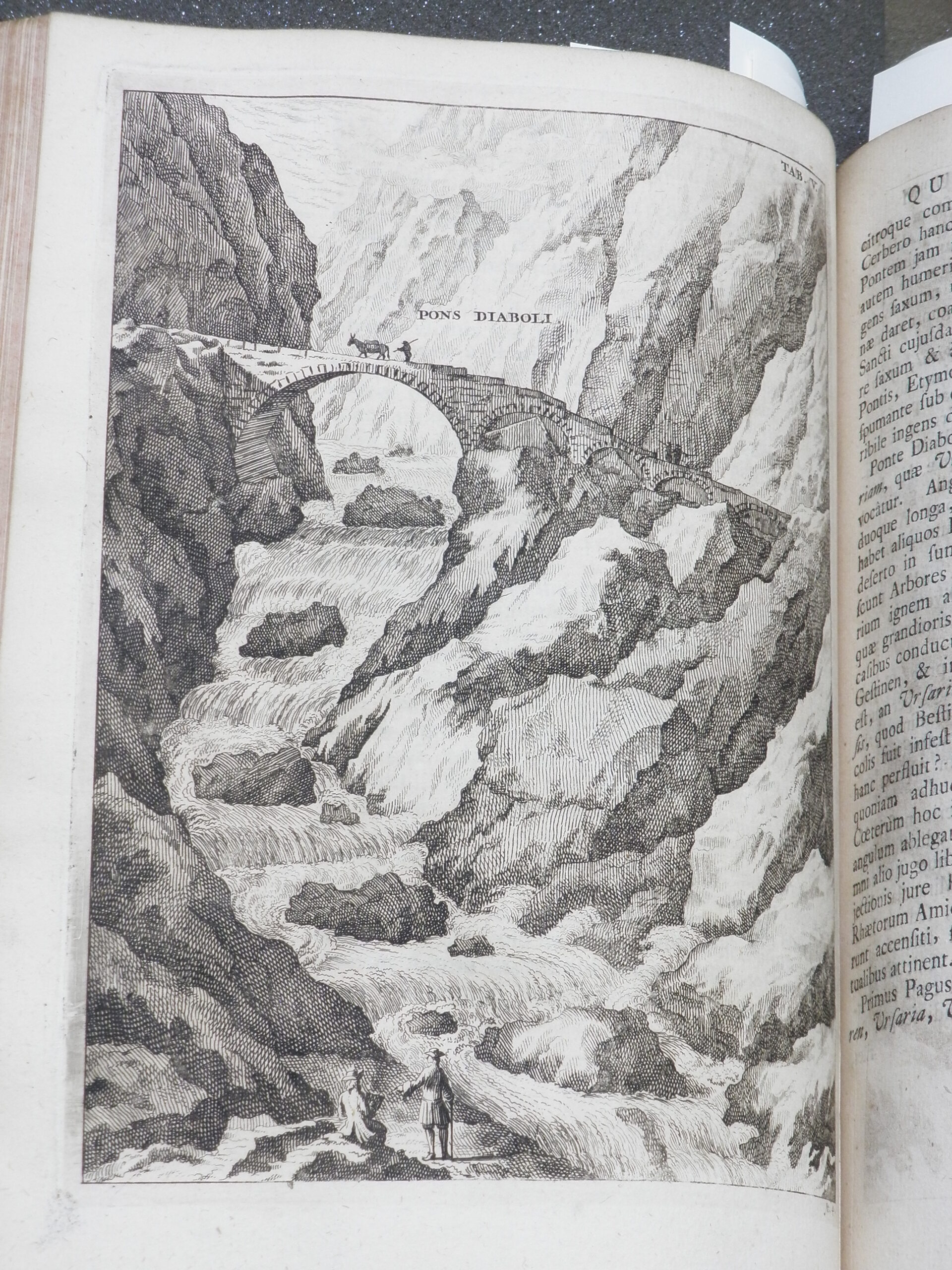

Johann Jakob Scheuchzer (1672-1733) was a Swiss scholar, physician and librarian, with a great interest in the natural sciences. Writing in Latin, and thereby addressing an international audience (see Barton, Mountain Aesthetics, page 153), Scheuchzer intended his work to inform on all manner of things Swiss. It is a highly visual volume, extensively illustrated with 121 prints (all of which have been digitized online on the VIATIMAGES database), including maps, town-plans, alpine scenery of peaks and waterfalls, illustrations of scientific and mechanical devices, botanical drawings, and images of fossils, crystals, and glaciers. Such illustrations were ‘intended to show the true nature of things at the most basic level of science and knowledge’ (Leu, ‘Swiss mountains and English scholars’, page 336).

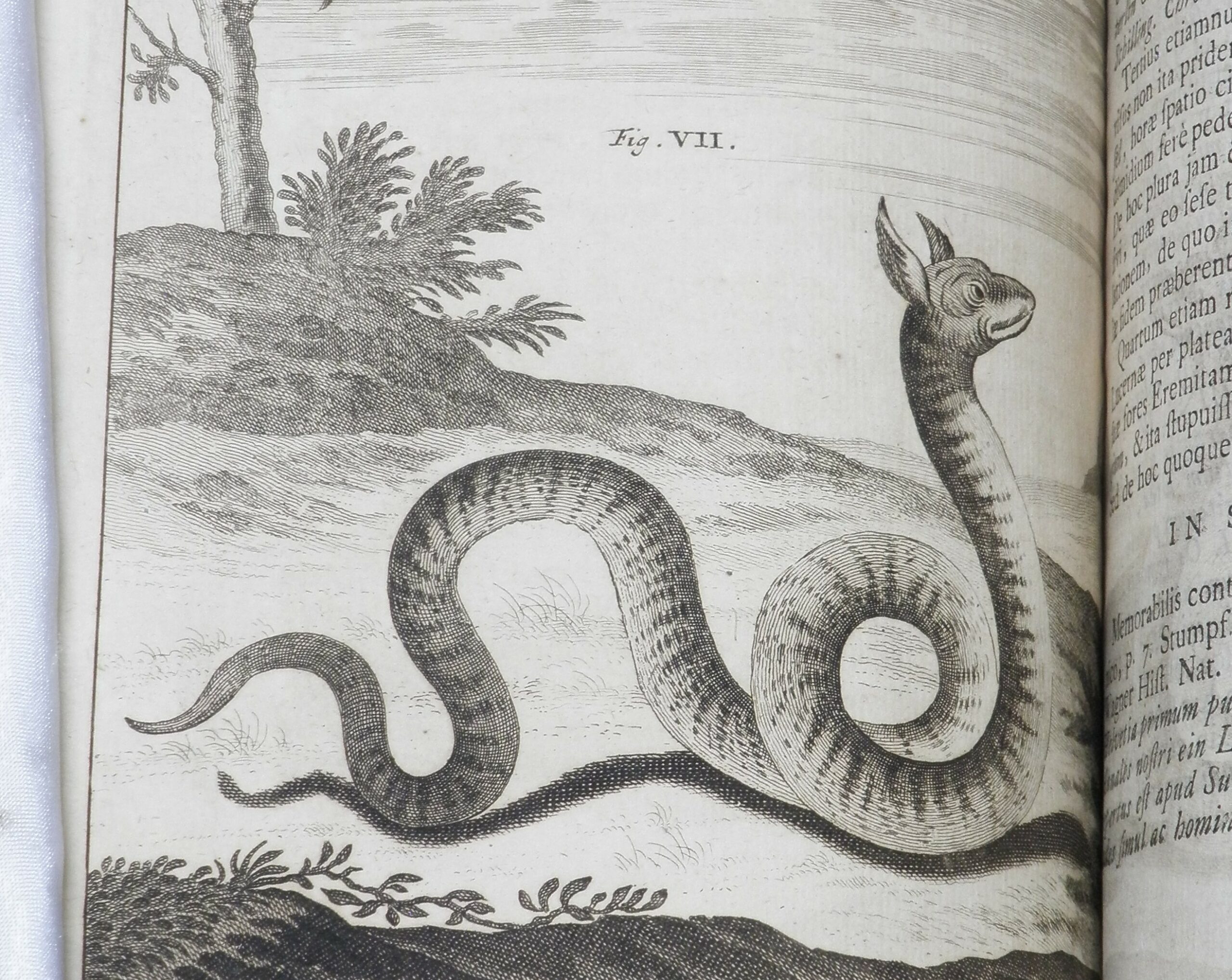

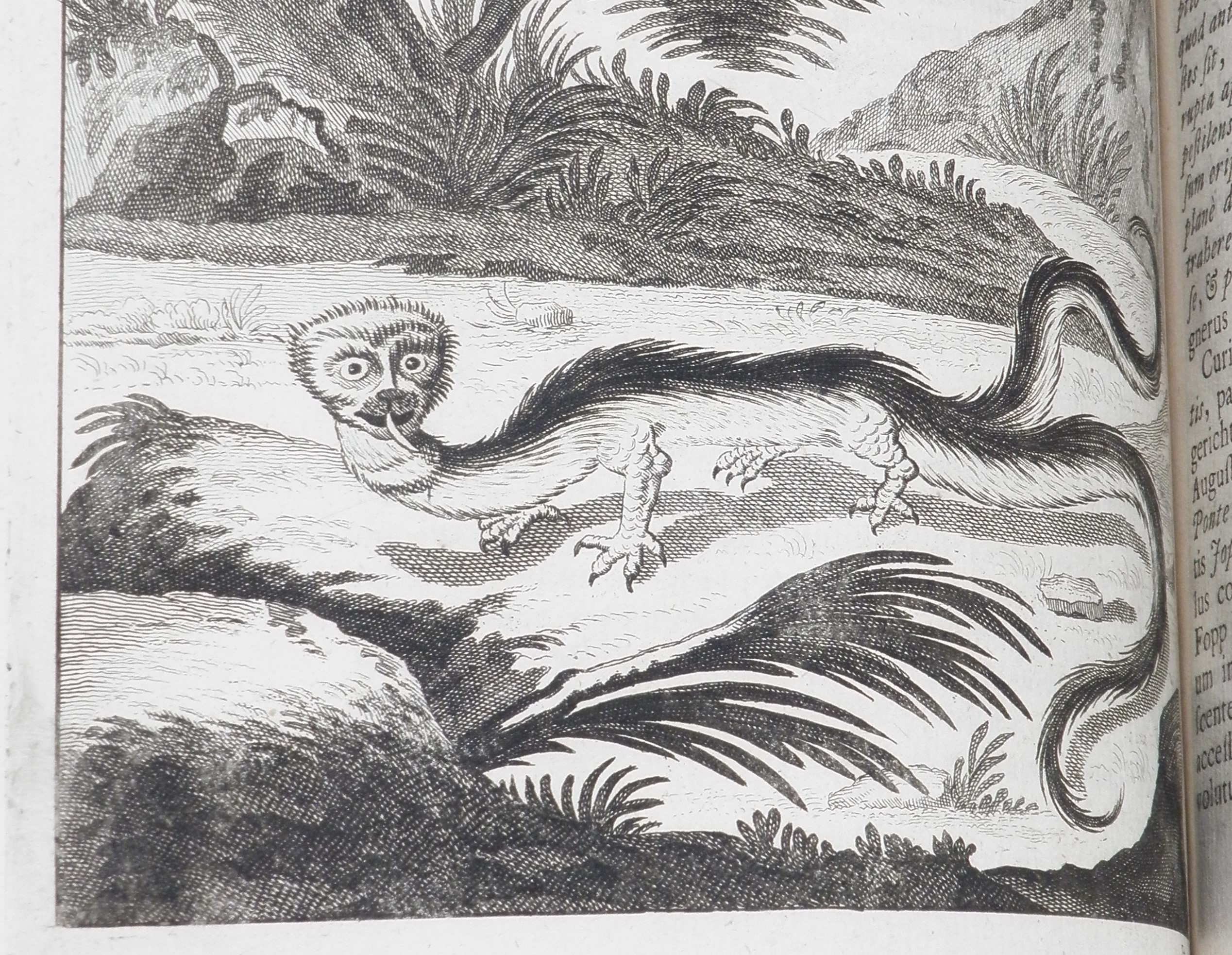

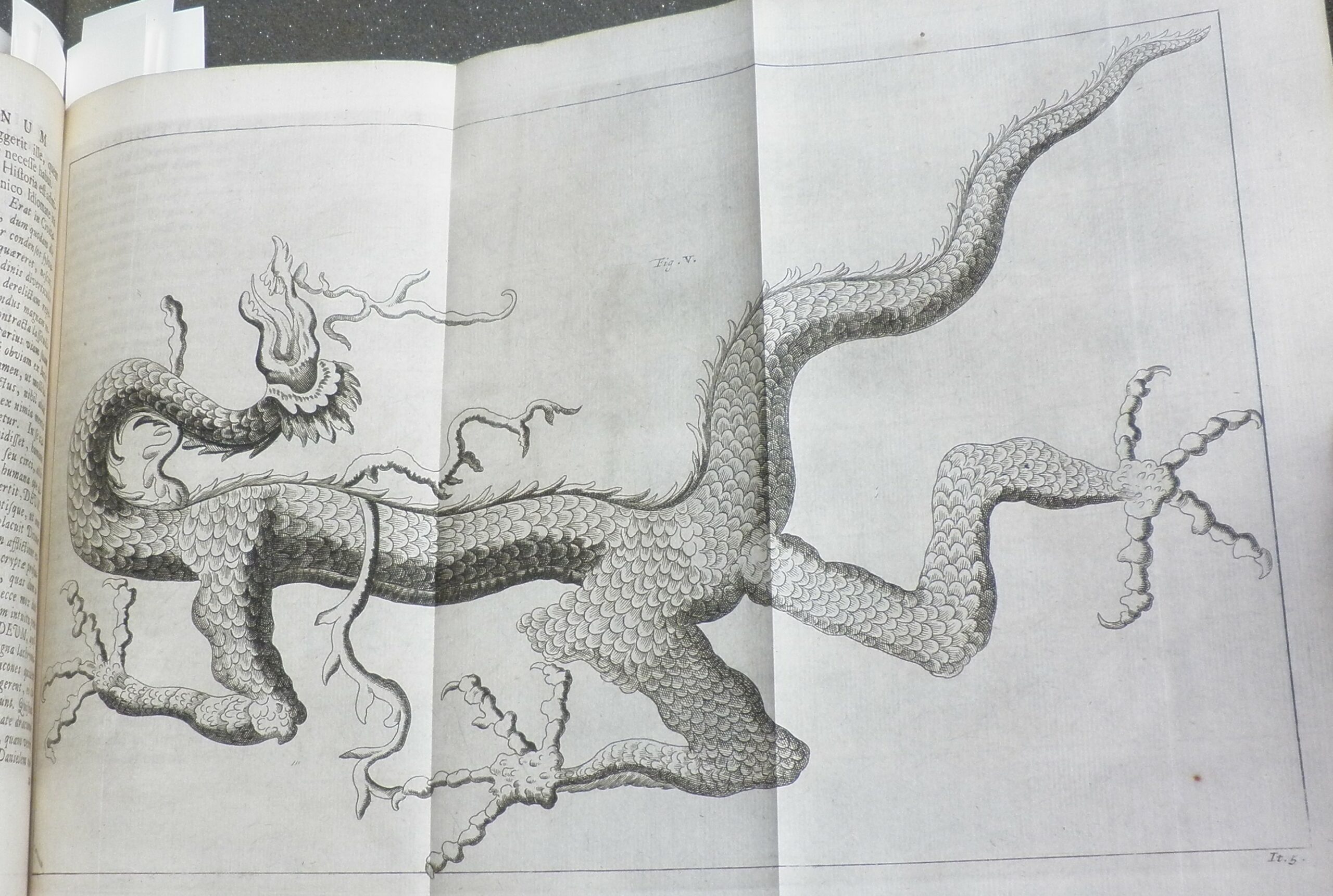

As Librarian of Zurich’s city library, Scheuchzer was also curator of that library’s Kunstkammer, its natural history and art collection, and his own book has a certain affinity with 18th-century cabinets of curiosities. Indeed, it is with an item seen in a museum, the Dragonstone of Lucerne (the Draconita Lucernensis, pages 367 ff.), that Scheuchzer begins perhaps the most unusual section of his work: his enquiry into Swiss dragons, undertaken as part of his fifth journey in 1706. Beginning with literary sources and including oral accounts, Scheuchzer investigated the myths of dragons supposed to dwell within the dark mountains and caves of the Swiss Alps. Included are narratives of those individuals who claimed to have seen dragons:

‘Near the end of summer 1717 Joseph Scherer from Näfels came across… an animal with the head of a cat and protruding eyes; it was a foot long, with a thick body, and two breast-like things hanging from its stomach, and also with a foot-long tail; it [the whole creature] was covered in scales and of many hues. He stabbed it with a sharp stick, and claimed that it was soft and full of a virulent blood, which dropped on his leg, at which his leg swelled up… ’

(translated from the Latin, page 391)

Scheuchzer even attempted a taxonomy of these dragons, distinguishing between those with or without wings, those with feline or reptilian features, and those with or without crests. Although unwilling to discount the possible existence of dragons, Scheuchzer’s scientific approach did mean that he provided rational explanations for some of these sightings and accounts: examining bones said to be of a dragon, he identified them as ‘the bones of a bear’ (see page 390). He also noted that rivers were called ‘dragons’ by Alpine locals:

‘In the last place I should not fail to mention that, among our Alpine peoples ‘dragon’ is a homonym for a fierce torrent; for, whenever a river rushes through the Alpine passes with a great force and snatches rocks, trees and other things of huge size with itself, these people are accustomed to say: “It is a dragon that has passed through”. The swiftness of dragons perhaps gave the occasion to this phrase, and to it can be ascribed the false histories of many of the dragons which circulate among the population….”

(translated from the Latin, page 396)

Thankfully such explanations did not prevent him from illustrating the region’s so-called dragons in eleven plates. Prints to which one can continually return with great pleasure.

Mark Bainbridge, Librarian

Bibliography

- Barton, W., Mountain aesthetics in early modern Latin literature (London, 2017)

- Leu, U.B., ‘Swiss mountains and English scholars: Johann Jakob Scheuchzer’s relations to the Royal Society’, Huntingdon Library Quarterly, vol. 78, no. 2 (Summer 2015), pages 329-348