What books would you take to a desert island?

29th March 2019

What books would you take to a desert island?

Article from The Listener in the papers of Sir Llewellyn Woodward (Professor of Modern History 1948-1951)

Last summer the College Archives moved into newly renovated accommodation, providing three store rooms and an office/reading room, thanks to the generosity of the Wilkinson Trust and funds from the estate of Professor James Campbell. The historian James Campbell, subject of our January 2019 blog post, was the first Keeper of the Archives at Worcester College, taking office in 1960, and the new building is named the James Campbell College Archives in his honour.

Dedication plaque in the James Campbell College Archives building, 2018

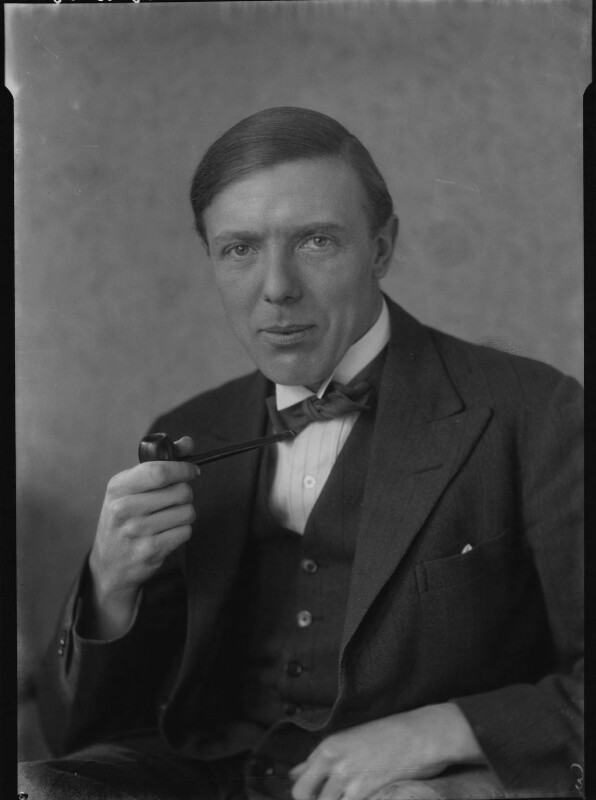

Shortly after James Campbell’s appointment as Keeper of the Archives, a former fellow of the College approached the Governing Body for permission to build a house in the College grounds, in which he could spend his retirement. Sir Llewellyn Woodward had been the first Professor of Modern History and a Fellow of Worcester College from 1948 until 1951, after many years as a fellow of All Souls and then New College. He moved to the United States in 1951 for a research professorship at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton but returned to settle in Oxford following his retirement in 1961. The Governing Body of Worcester College granted permission for his “Garden House” in 1963, which he promised to bequeath to them on his death. It is this building that has now been converted into the James Campbell College Archives and, as part of our collections of personal papers, it holds the papers of Sir Llewellyn Woodward.

Sir (Ernest) Llewellyn Woodward by Lafayette; half-plate nitrate negative, 26 October 1928, NPG x42999 © National Portrait Gallery, London

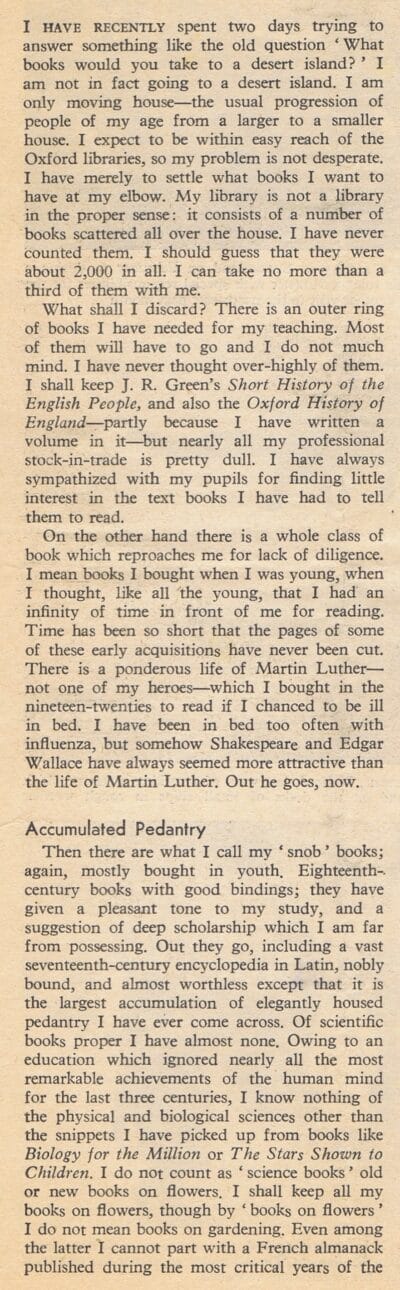

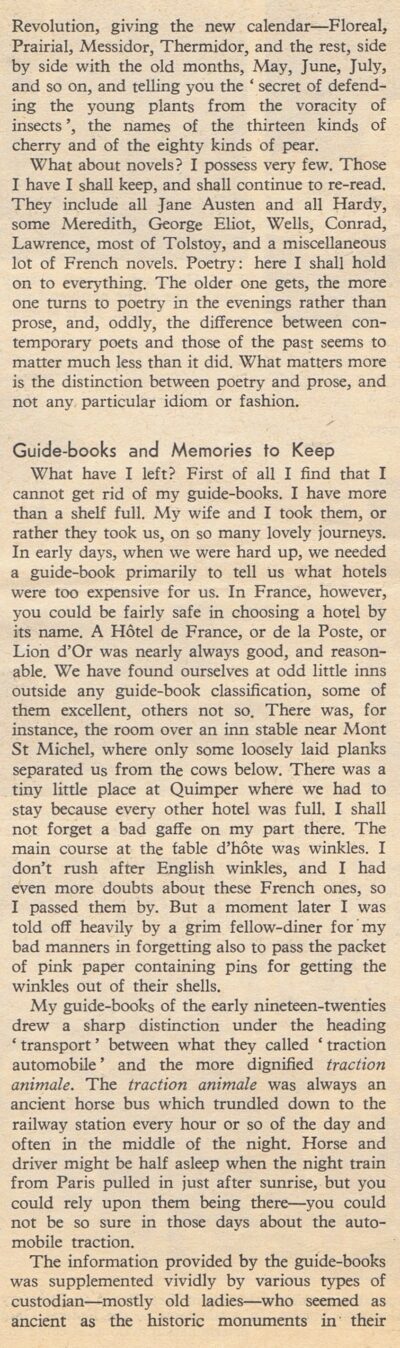

Among these papers is an article that Woodward published in The Listener on 14 February 1963. It caught my attention as it describes a dilemma currently in the spotlight after the success of Marie Kondo’s books and television series:

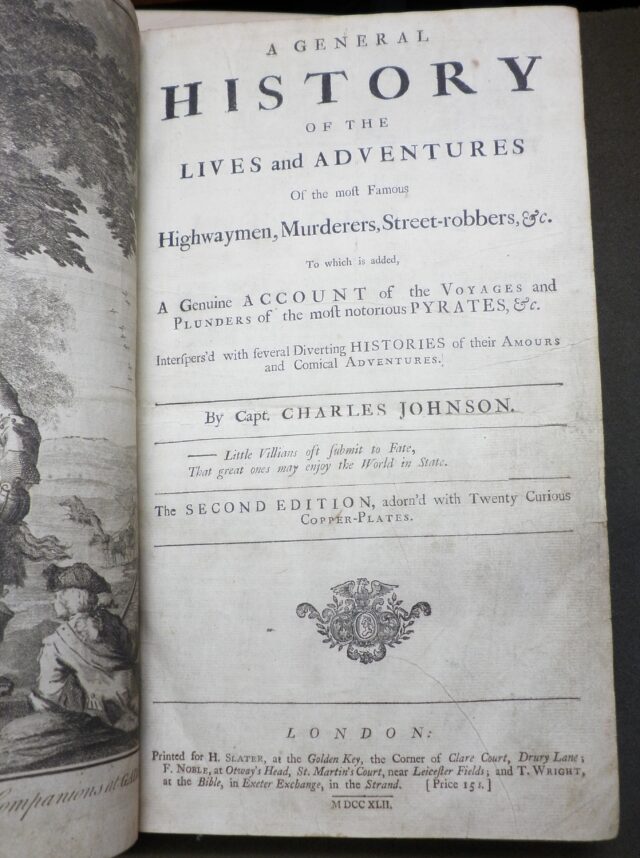

In preparation for the move to the newly constructed Garden House it was necessary, due to constraints of space, for Sir Llewellyn Woodward to reduce his personal library of about 2,000 books by two thirds. He set about the problem by posing to himself the old question: “What books would you take to a desert island?”, although he admitted that his situation was not quite that desperate as he would remain within easy reach of the Oxford libraries.

First to go were “books I have needed for my teaching” which, it seems pretty reasonable to state, did not “spark joy”:

Most of them will have to go and I do not much mind. I have never thought over-highly of them…nearly all my professional stock-in-trade is pretty dull.

The following paragraph is also relatable to any life-long collector of books. Woodward quickly determines that those books he bought intending to read at a later date, but which have never commanded his attention (he mentions a ‘ponderous’ life of Martin Luther as an example), would be next; similarly, his ‘snob’ books, which he bought to give “a suggestion of deep scholarship which I am far from possessing,” will now also have to go.

After this cull, Woodward had space for his novels, which he stated he would continue to re-read. “They include all Jane Austen and all Hardy, some Meredith, George Eliot, Wells, Conrad, Lawrence, most of Tolstoy, and a miscellaneous lot of French novels”. But his real preference as he got older was for poetry to read in the evening.

In addition to these, he kept a selection of reference books: travel guides for the memories they prompted of holidays with his wife (who had died in 1961), the Oxford English Dictionary, and all 22 volumes of the Dictionary of National Biography. These last two he considered to be so important that they must be kept despite the shelf room they ate up “even if I have to give them the space otherwise claimed by a television set”. It is not recorded whether Llewellyn Woodward and his sister, who came to live with him in the Garden House, had to do without a television in order to fit these worthy reference books onto the shelves. How much more space he would have had were he moving today, though, when both of these works are available online.

Full text of Woodward’s article

(click on article text)

- Article (part 1)

- Article (part 2)

- Article (part 3)

- Article (part 4)

- Article (part 5)

- Article (part 6)

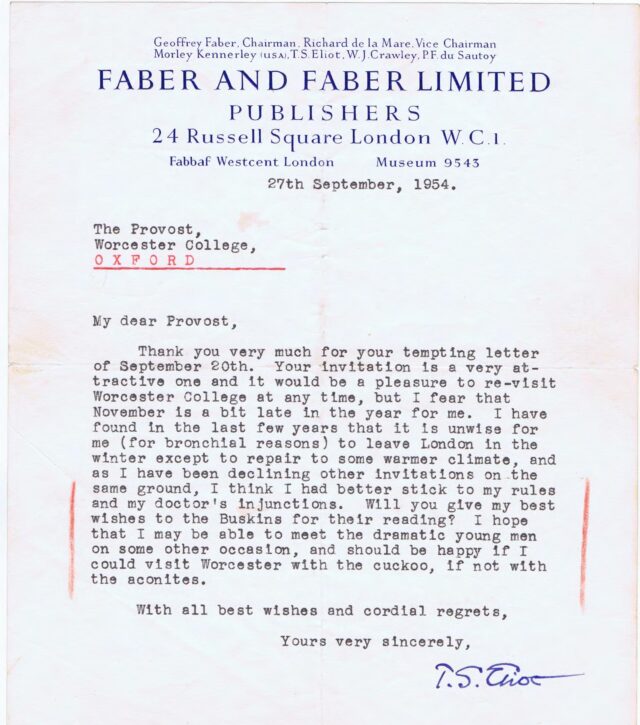

Sir Llewellyn Woodward lived in the Garden House, with his collection of essential books, until his death on 11 March 1971. There is no evidence that he gave any of his books to the College Library, either in 1961 or following his death, but the College Archives has his collection of personal papers, which includes manuscripts of his books, correspondence regarding their publication, personal letters, and also copies of articles he wrote, including this one from The Listener, which is so universally resonant with the feelings of bibliophiles, particularly those forced to make space by reducing their collection.

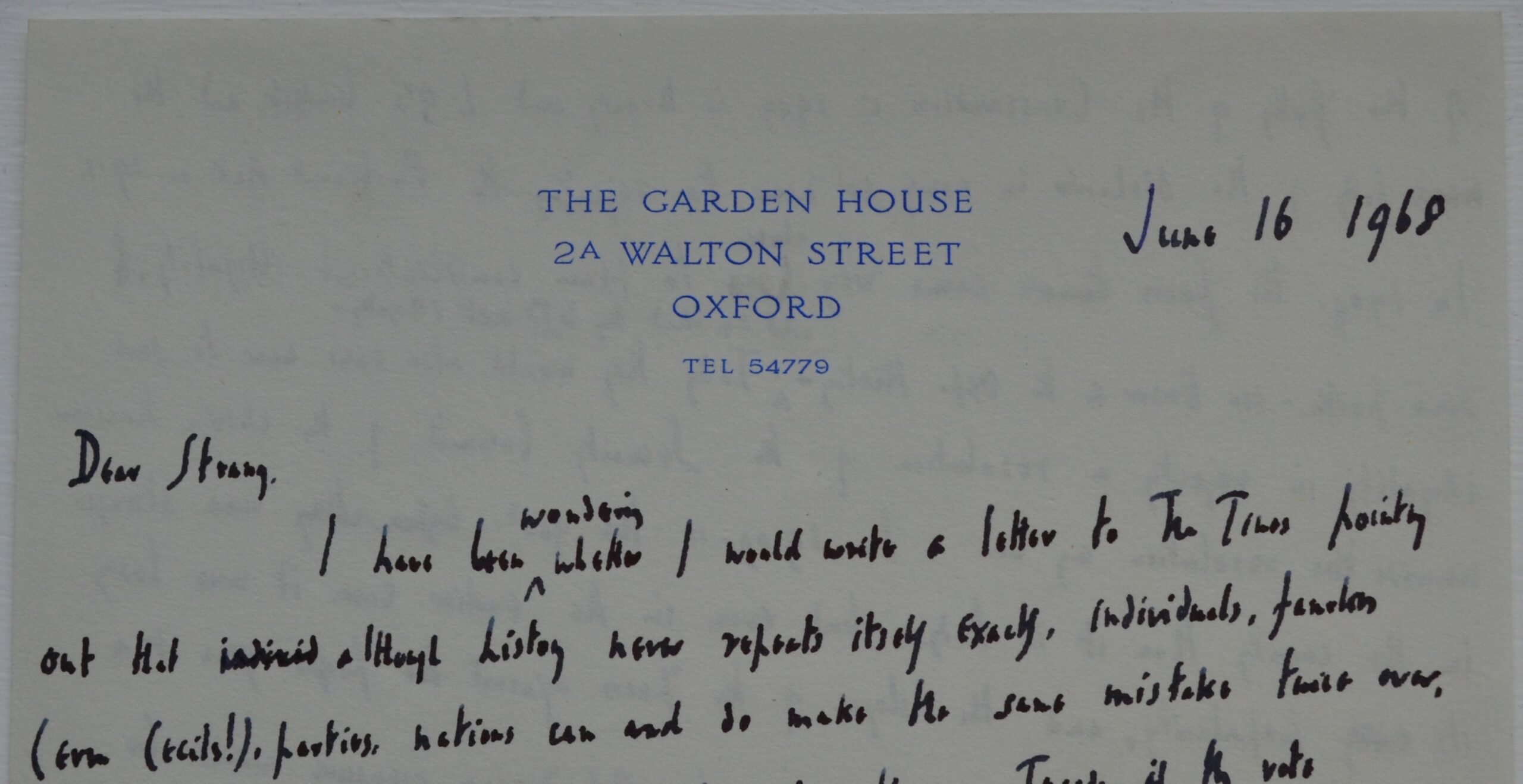

Letterhead with the Garden House address, on a letter from Woodward to Lord Strang

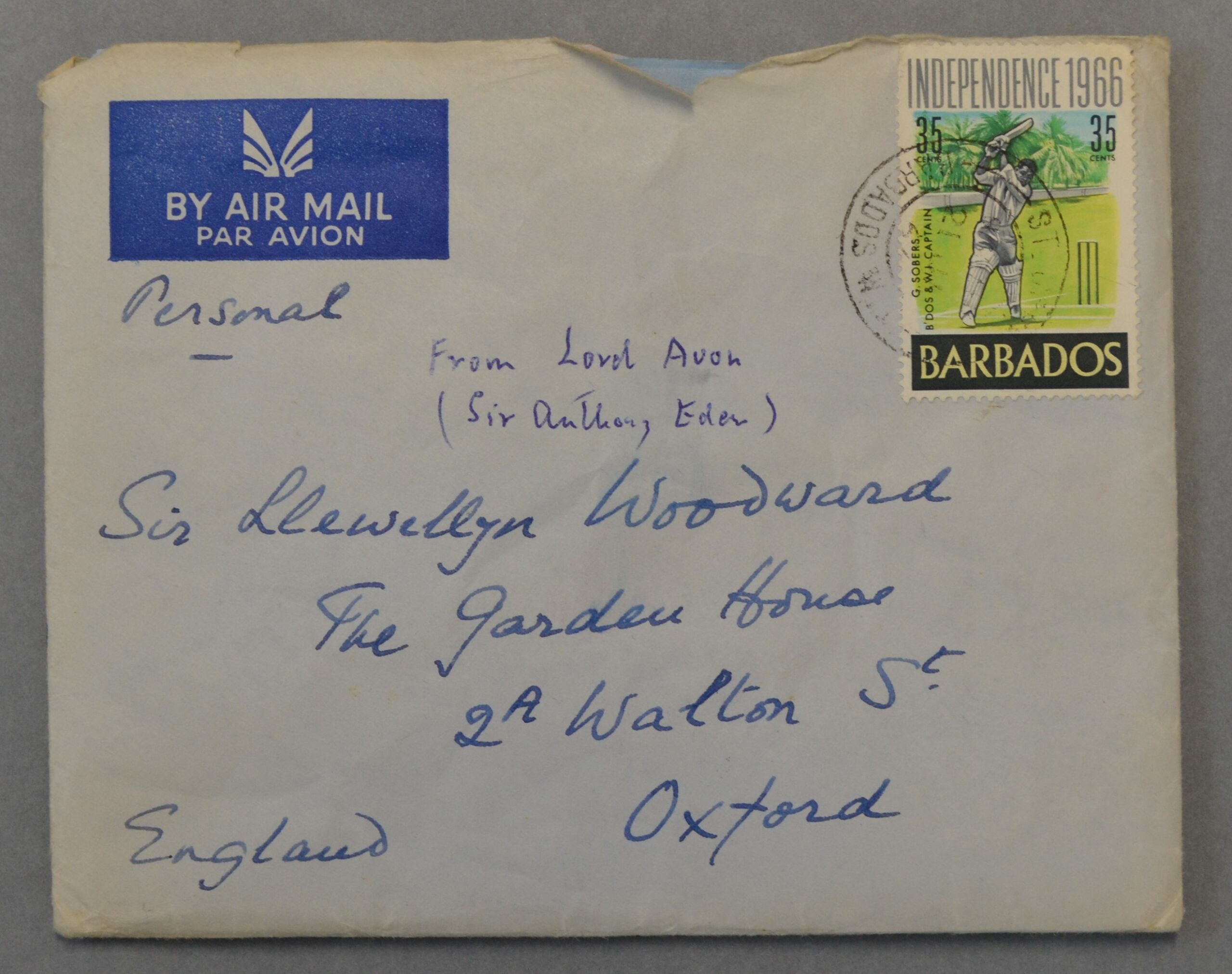

Letter addressed to Woodward at the Garden House by Lord Avon (Anthony Eden)

It is paradoxical that Woodward was required to reduce his personal library in order to move to the Garden House, when a major factor in converting this building for the Archives was the increased space it provides. The entire collection, including the papers of Sir Llewellyn Woodward, are now housed in a building that will ensure their long-term survival and increase their availability to researchers. A use for the “Garden House” of which Woodward, who edited the Documents on British Foreign Policy series and used government archives extensively, would surely have approved.

The James Campbell College Archives building

Emma Goodrum, Archivist

Bibliography

- Wernham, R. (2006, May 25). Woodward, Sir (Ernest) Llewellyn (1890–1971), historian. Revised by M.E. Chamberlain. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 8 Mar. 2019, from https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/31857.