Traces of medieval music

20th May 2016

Traces of medieval music

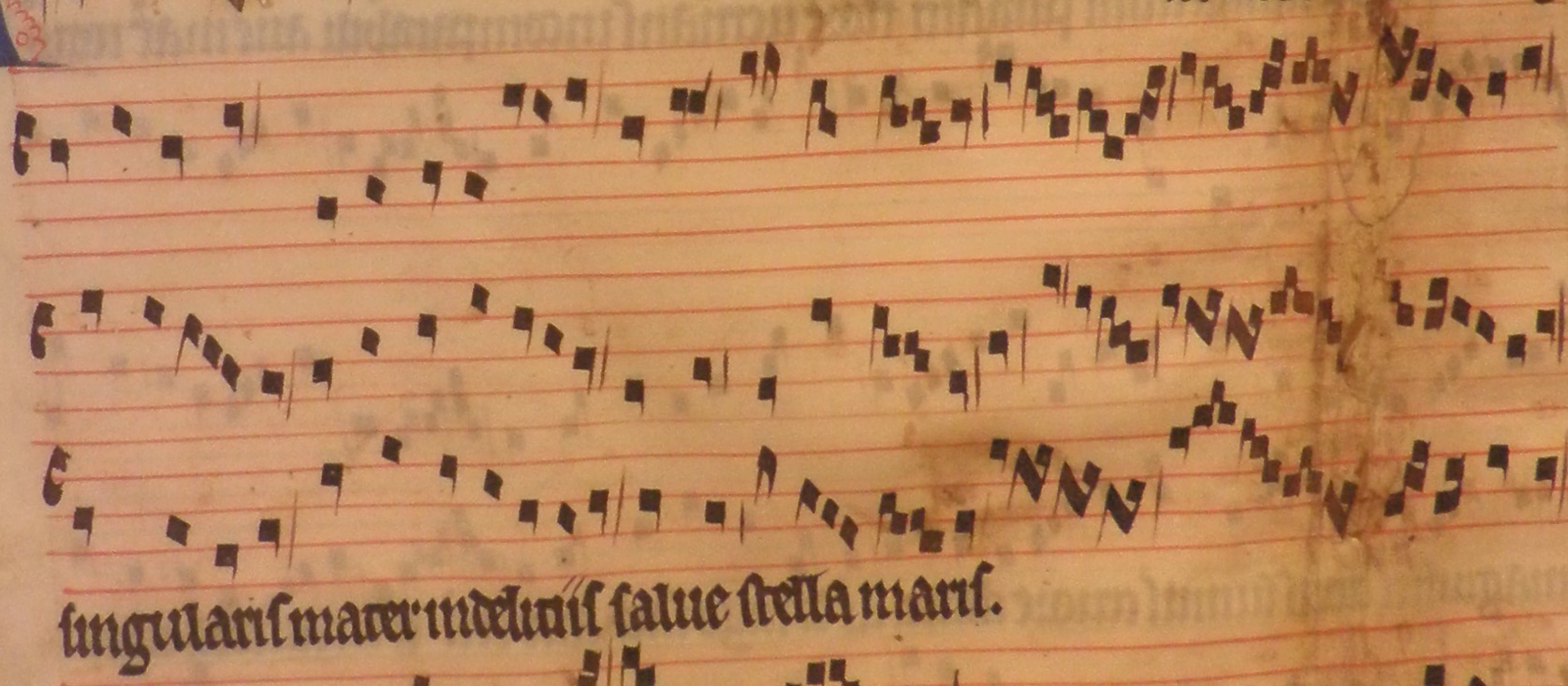

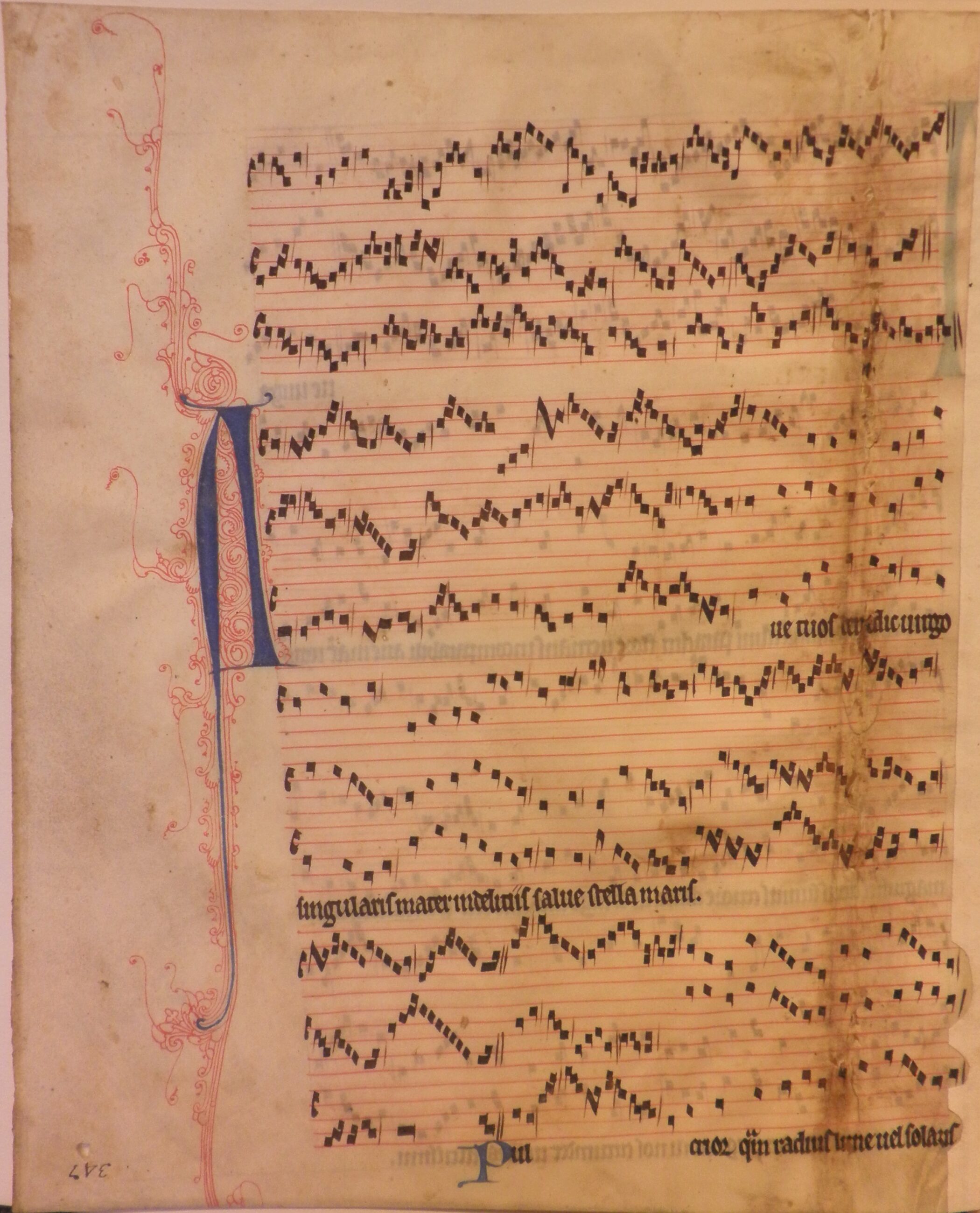

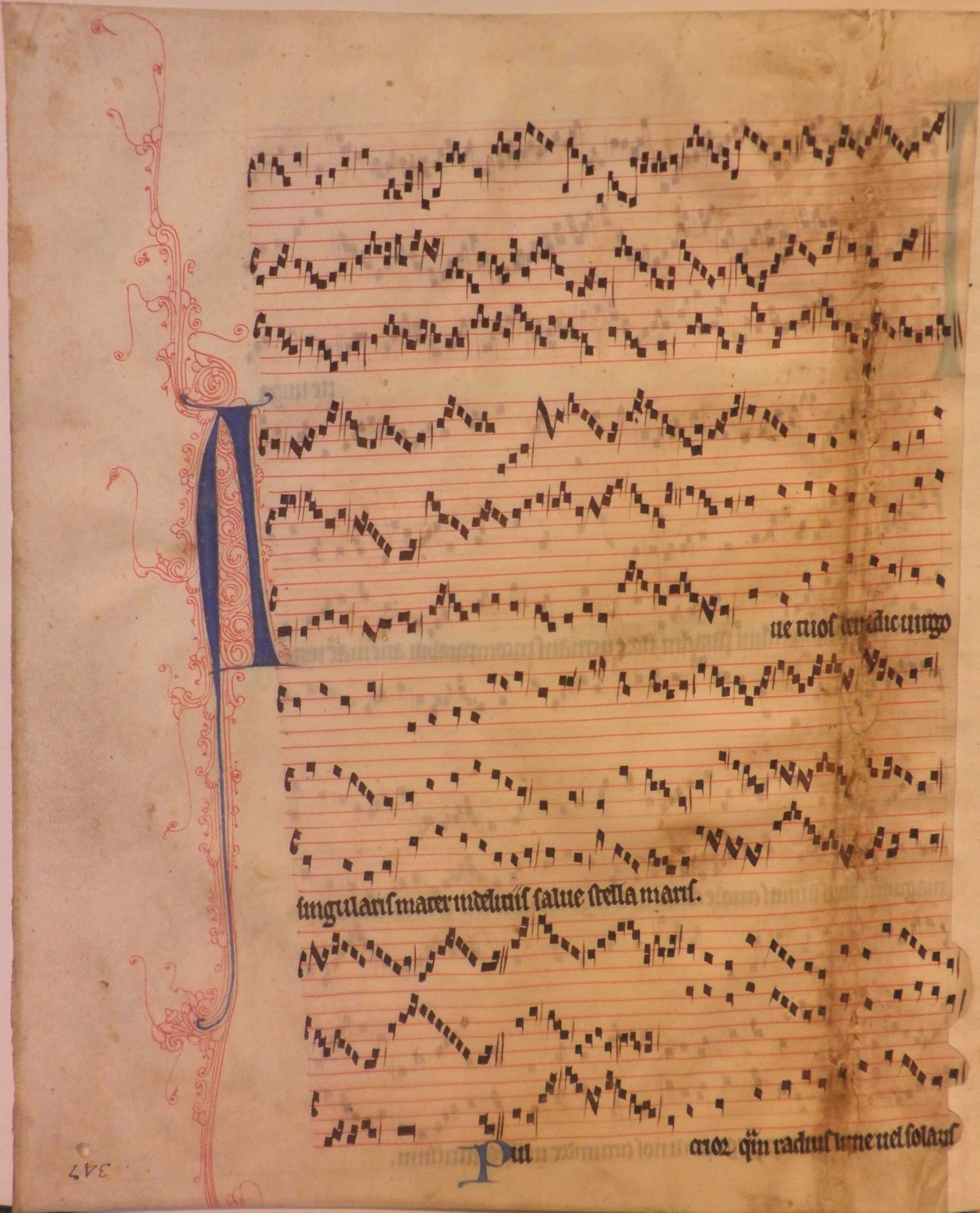

MS 213* – Fragments of medieval music, Reading Abbey, second half of the 13th century

Our treasure for this month is not a book, but two fragments of parchment from the thirteenth century containing a few staves of vocal music. The sheets of music were used as flyleaves in the binding of a larger manuscript (MS 213), but have since been detached from the manuscript and bound separately. The parent volume is a book of annals and devotionals from Reading Abbey, written primarily in the thirteenth century. The manuscript was donated to the Abbey by Prior Alan (known to be prior in 1290) and was probably compiled in Reading, as the annals focus on events related to Reading and its Abbey (Coates, English Medieval Books, p. 72).

MS 213* Fol. 1 verso

The fragments are sacred polyphony, described as a ‘Conductus cum cauda’ by N.R. Ker in his entry on MS 213 and MS 213* in Medieval Manuscripts in British Libraries. Conductus was a common style of composition popular in Northern France and England in the twelfth – thirteenth centuries. It is based on poetic forms and often included cauda – melismatic passages. Polyphony developed in the later middle ages and was used primarily for elaboration and adornment in the most important services of the church year and in the more significant aspects of masses and offices (Harrison, Music in Medieval Britain, p. 104). Large Benedictine abbeys played a significant part in the development of polyphony and Notre Dame in Paris was particularly influential throughout the Anglo-French world (for more see Harrison, Music in Medieval Britain, and Gushee, ‘Polyphonic Music’).

This influence is evident in our musical fragments. The notation is described as ‘Notre Dame’ type in the International Inventory of Music Sources (RISM) entry for the manuscript, which denotes the use of rhythmic modes – a style of rhythm and notation heavily associated with the Notre Dame school and the development of polyphony (‘Notation’, Oxford Companion to Music). Grove Music defines rhythmic modes as:

‘The modern name for a medieval concept of rhythm in which the value and relative duration of each note is determined by its position within a larger rhythmic series, or mode, consisting of a patterned succession of long and short values.’

Modes were notated using combinations of square notation and ligatures, but the contextual nature of rhythmic modes meant that the notation was often rhythmically ambiguous (Pesce, ‘Theory and Notation’, p. 283).

That musical fragments originating in Reading show strong French influences should come as no surprise. From the time of the Norman Conquest, England and Northern France had become closely entwined culturally as well as politically. French clerics were prominent in the monastic houses of England, and Reading, as a large Benedictine monastery, would have had close contacts with its continental counterparts. Several scholars have emphasised, however, that this influence went both ways. Crocker draws attention to the presence of distinctive elements of English polyphony – voice exchange and imperfect consonances – in Notre Dame compositions as evidence of this mutual cultural exchange (‘Polyphony in England’, pp. 688-9).

The abbey at Reading itself seems to have been an active centre of musical composition in the 13th century. The fragments in Worcester are not the only ones to survive from the abbey’s collections. The most famous is a manuscript known as ‘Sumer is icumen in’, which is now held in the British Library and is considered to be one of the most significant surviving sources of English medieval music (for more see Coates, English Medieval Books, and Harrison, Medieval Music in Britain).

Sadly, our fragments here are typical of what often survives of medieval music. Many liturgical books were destroyed during the Reformation. Much of what survived was repurposed in binding – as flyleaves or pastedowns. Even at the time, written music wasn’t always intended to be permanent. Musical fashions change just as any other and it was common in the middle ages to take apart old books to make new ones (Bell, ‘Music’, p. 466).

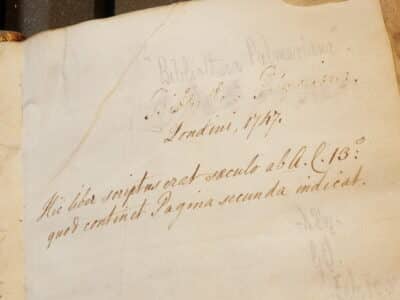

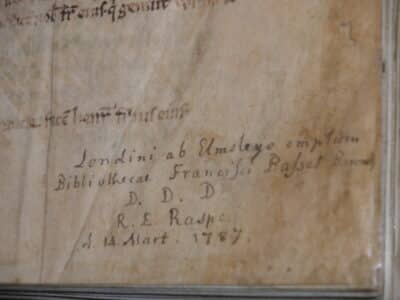

Where our fragments went following the dissolution of the monasteries is a mystery but we can pick up the trail in the eighteenth-century from various ownership markings in the parent volume. The next record of ownership is an inscription reading ‘Bibliotheca Palmeriana Londini 1747’. It was probably around this time that the manuscript was bound (or rebound) in gilt morocco, with the musical fragments as flyleaves. Coates identifies this owner as Ralph Palmer of Little Chelsea, who then passed the manuscript to his grandson, Ralph, first Earl Verney. From there it went to Verney’s son, Ralph, second Earl Verney, who affixed his own bookplate to the inside cover. The second Earl Verney is described by the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography as a substantial landowner who inherited a large fortune and ‘squandered this wealth through ruinous extravagance, injudicious business dealings, and an absurd generosity that also destroyed his parliamentary interest’. Perhaps it is not surprising then that the manuscript was sold in 1787 to Sir Francis Basset of Tehidy, a landowner and politician.

- ‘Bibliotheca Palmeriana’ inscription

- Inscription of Sir Francis Basset

- Bookplate of Sir Francis Basset

The last mark of ownership is that of George Dunn, who acquired the manuscript in February 1907. Dunn was a noted bibliophile and built a substantial library over his lifetime, rich in medieval manuscripts and early printed books (brief biography at Archives Hub: http://archiveshub.ac.uk/data/gb133-engmss206-207). MS 213 was not listed in the sales of his library which followed his death in 1912 however, which suggests that it had already changed possession. Perhaps it had already been acquired by Worcester by then, but the first record of it here is from the College Record of 1937-1938:

‘Another MS recently placed in the Library is a volume of prayers, devotions, meditations, etc. At the beginning are fragments of a chronicle from the year 1000, and these contain what are possibly the two earliest references to Gloucester College…’ (Worcester College Record 1937-1938 p. 8)

Here we have the likely reason why the manuscript was acquired by or for Worcester -because it contains two of the earliest known references to Gloucester College, Worcester’s medieval predecessor, a Benedictine establishment which stood on the site of the current college. In a way then, the manuscript and its fragments of music have come full circle. As a Benedictine foundation, Gloucester College served Benedictine houses such as Reading. Individual monasteries had rooms in the college for their monks who came to study in Oxford (evidence of which can still be seen in the coats of arms above the doorways in the medieval cottages). We can never know who exactly composed or transcribed the music in these fragments, but it is possible, however remotely, that they might have once been a student in these very grounds.

Engraving of Gloucester Hall, by David Loggan, 1675. Gloucester Hall was established on the site of Gloucester College following the Dissolution of the Monasteries, and was rebuilt as Worcester College in the early eighteenth-century.

Renée Prud’Homme, Assistant Librarian

Bibliography

- Bell, Nicolas, ‘Music’ in The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain Vol. II: 1100 – 1400, ed. Nigel J. Morgan and Rodney W. Thomson (Cambridge 2008)

- Coates, Alan, English Medieval Books: the Reading Abbey Collections from Foundation to Dispersal (Oxford 1999)

- Crocker, Richard, ‘Polyphony in England in the Thirteenth Century’ in The New Oxford History of Music Vol. II: the Early Middle Ages to 1300, ed. Richard Crocker and David Hiley (Oxford 1990)

- Gushee, Marion S., ‘The Polyphonic Music of the Medieval Monastery, Cathedral, and University’ in Man and Music Antiquity and the Middle Ages: from Ancient Greece to the Fifteenth Century, ed. James McKinnon (Basingstoke 1990)

- Harrison, Frank, Music in Medieval Britain (London 1958)

- Ker, N.R., Medieval Manuscripts in British Libraries Volume III (Oxford 1983)

- Pesce, Dolores, ‘Theory and Notation’ in The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Music, ed. Mark Everist (Cambridge 2011)

- Patrick Woodland, ‘Verney, Ralph, second Earl Verney (1714–1791)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/28234, accessed 23 March 2016]