‘Cyphers’ and the death of Oliver Cromwell: Sir William Clarke’s papers

30th April 2019

‘Cyphers’ and the death of Oliver Cromwell: Sir William Clarke’s papers

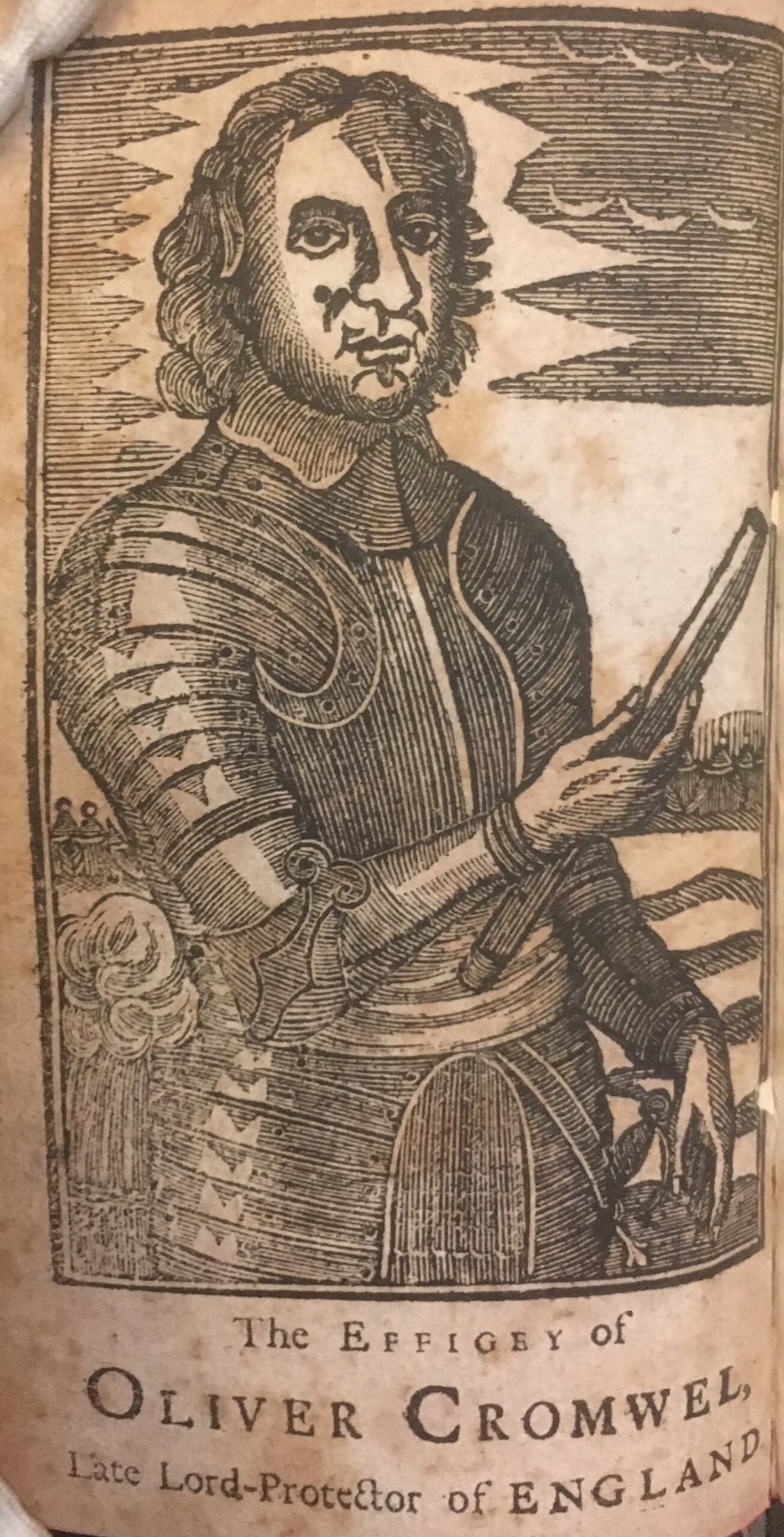

Oliver Cromwell from the copy of a 12o edition of J. Heath’s The life of Oliver Cromwel (London, [1715?]) owned by C.H. Firth

This month we return to the subject of the very first Treasures blog post: Sir William Clarke, father of Worcester Library’s first great benefactor – Dr George Clarke. Some of the riches left to Worcester by Clarke junior originated with Clarke senior, not least Sir William’s own papers, which we will focus on here. Yet in this case it took the College nearly two centuries to realise quite what a treasure it possessed.

The previous post looked at his presence as a secretary on the scaffold at Charles I’s execution, adducing as evidence a manuscript annotation he made to one item in the major collection of Civil War and Interregnum pamphlets that ultimately came to Worcester from Sir William via George. This one touches on the deathbed of Charles I’s successor as head of state, the pseudo-monarch Oliver Cromwell, nearly a decade later. Perhaps as important is the story of Clarke’s papers themselves.

One of William Clark’s original notebooks (Worcester MS XXX)

In the original Dictionary of national biography, the article on Clarke ran to just over 300 words – and the Clarke papers are mentioned fleetingly in the longer article on George only. For the new Oxford dictionary of national biography the article on Sir William (which includes a likeness) was four times as long. It was written by someone with an important role in the story of the Clarke papers, and to whom what follows owes more than citations can acknowledge: Dr Frances Henderson.

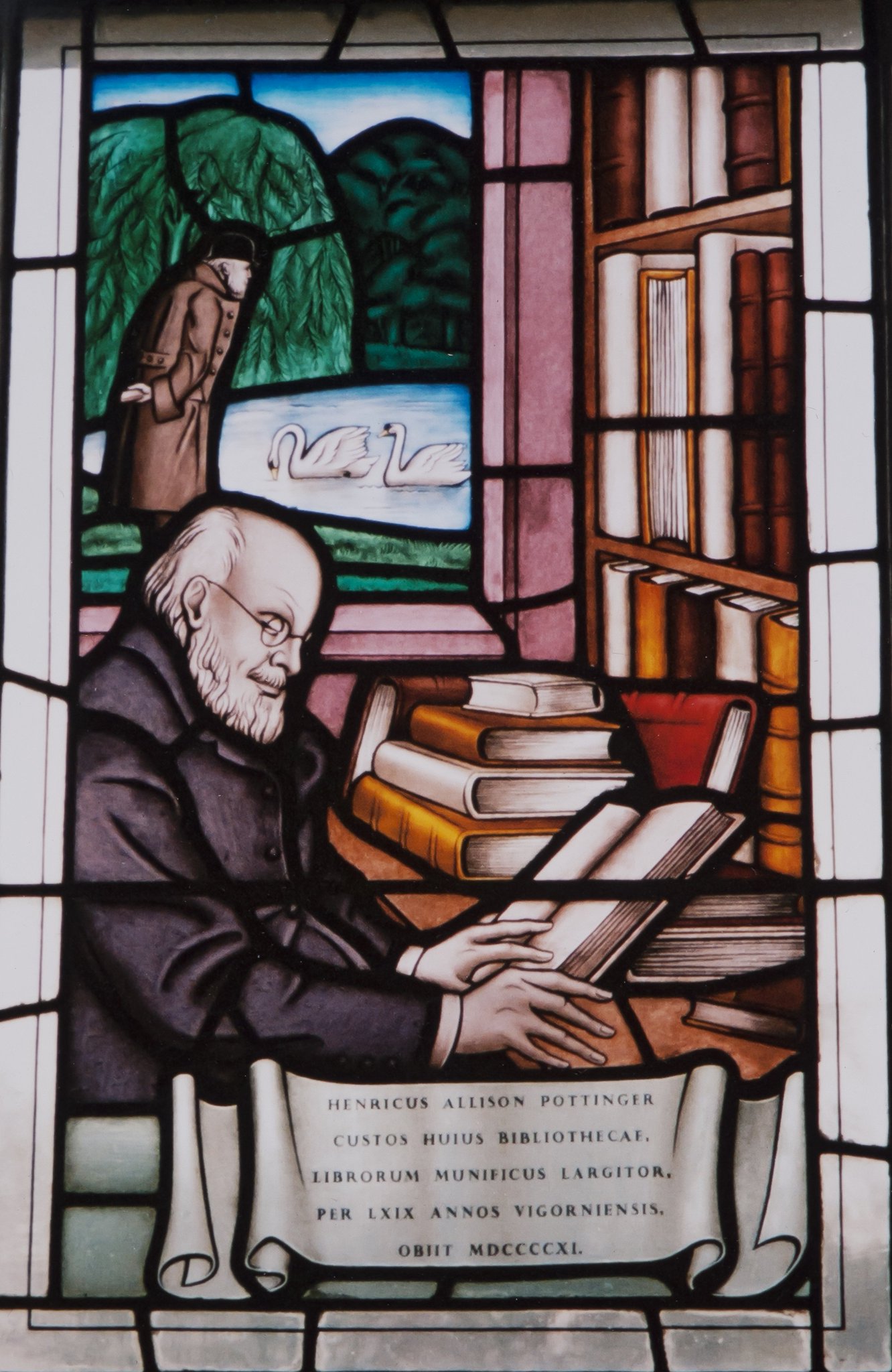

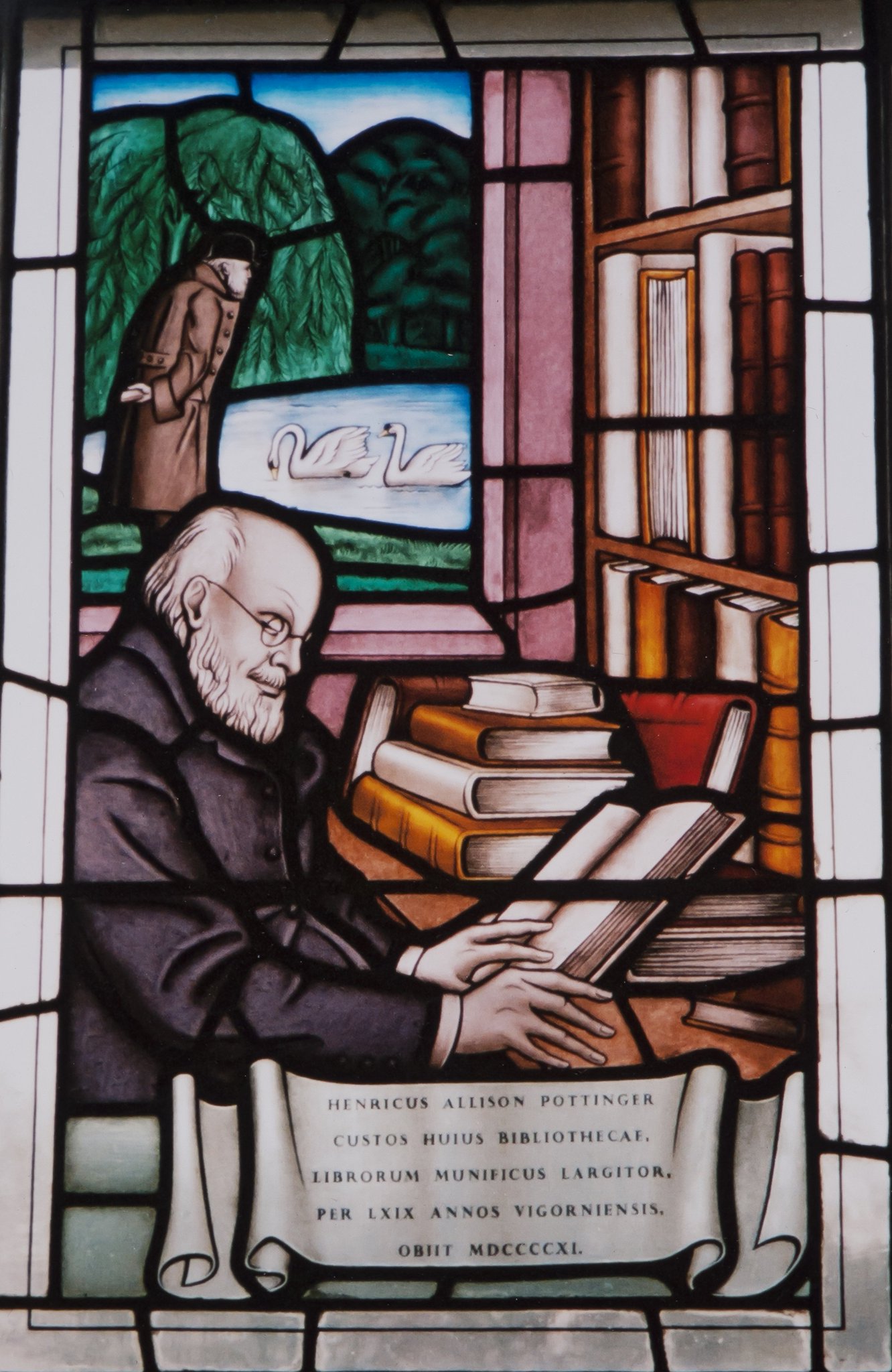

That Sir William warranted greater coverage one hundred years on was due to two benefactors of the Library, who were responsible for first bringing Sir William’s papers to wider attention: H.A. Pottinger and the historian C.H. Firth.

The Pottinger window in the Lower Library at Worcester

Though partially listed in (Worcester alumnus and Bodley’s Librarian) H.O. Coxe’s catalogue of college manuscripts, the papers were largely unknown and unused. Pottinger, librarian and fellow of Worcester, “a man of some eccentricity”, indeed a “bibliomaniac”, who has featured before in blog posts, “mentioned,”

quite casually perhaps, to a young historian of his acquaintance that there was some stuff in a cupboard in Worcester that might be worth his attention. The historian was C.H. Firth. (Le Claire, 2001, pages 20-1)

Between 1891 and 1901, Firth published four volumes of material from the Clarke papers for the Camden Society and two for the Scottish History Society. In a distinguished career, which included a spell as the Oxford Regius professor of modern history, he developed a reputation as a leading historian of the Civil War and Interregnum period, with a particular interest in the role of the parliamentarian army. This was linked to the Clarke papers, for Firth considered their “special value” to consist “in the light which they throw upon the history of the Army during the period when its political importance was greatest” (Firth, 1992, p. ix), indeed when it took a political role unique in modern British history. As S.R. Gardiner put it, the Clarke papers “[threw] every other accession of material into the shade” (Cited in Henderson, 1998, p. 71 and Woolrych, 1992).

William’s background and early career are obscure, but in his early twenties he seems to have become part of a nascent army secretariat, and as such was present as a note-taker at important events, e.g. the trials of Archbishop Laud and other senior Royalists. Firth records that Pottinger “discovered some additional volumes [of manuscript notes], including the most valuable of all” (Firth, 1992, page vii) containing an account of the famous Putney debates of 1647, at which ordinary soldiers expressed often radical ideas about the constitutional settlement that should follow the Civil War. Clarke’s notes from the debate helped in the twentieth century to revolutionise thinking about the period (Mendle, page 3 et seqq).

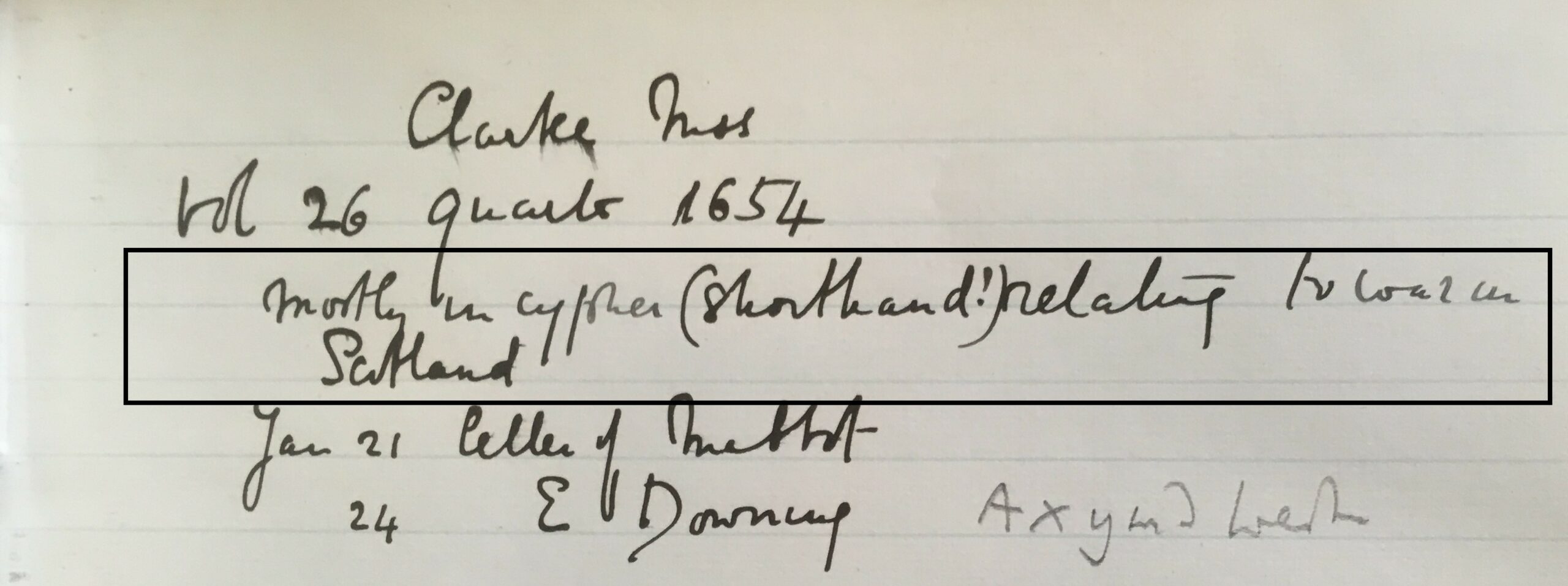

In the 1650s, William was based with the occupying English army in Scotland. However, when we come to the 1650s a major part of the papers’ contents remained missing from the picture until the 1970s. Up to his premature death in 1666, William had been writing up fair copies of his manuscript notes and destroying the originals. He had completed the task down to the early 1650s, but for most of that decade what we have are his working papers. This is significant because a good proportion was written not in longhand but shorthand, or as Firth initially seems to have believed a cypher. Worcester holds one of the notebooks made by Firth (and his research assistant or assistants) from the Clarke papers. Of volume 26 of the Clarke manuscripts, covering 1654, it is noted that they are “mostly in cypher (shorthand!) relating to war in Scotland”, though any assessment of their contents must have been speculative – usually only a date and place can be read easily. No attempt seems to have been made to elucidate the contents.

Firth’s notebook (Worcester MS CCXIV)

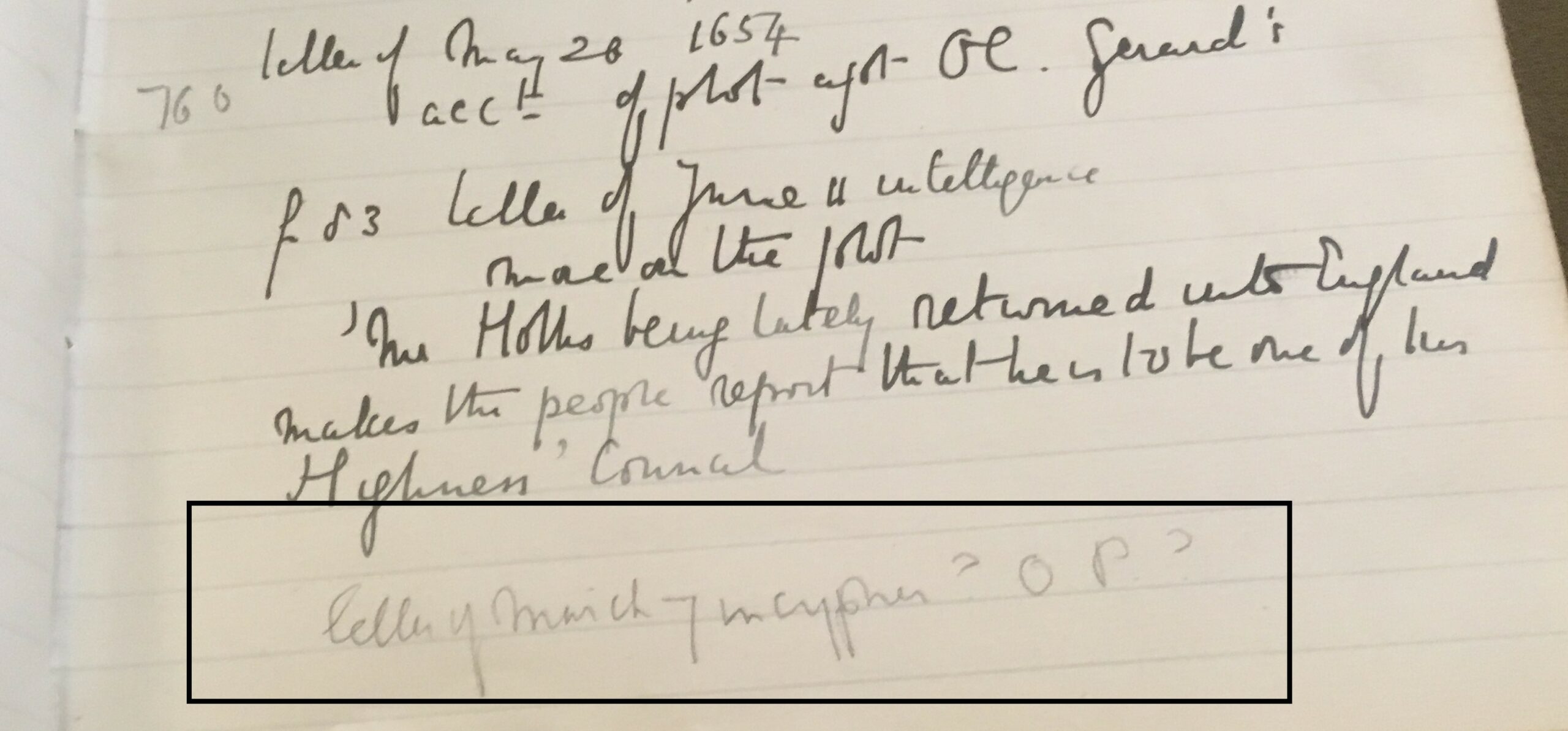

Another notes a “letter of March 7 in cypher? O P?”, i.e. Oliver P[rotector].

Firth’s notebook (Worcester MS CCXIV)

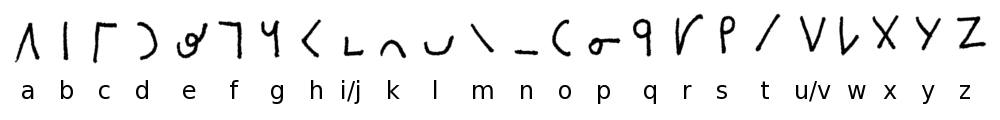

In his published text Firth scarcely alluded to this omission, and some historians may have made the convenient assumption that what was absent was of no great consequence. It was not until the 1970s that the cryptographer Eric Sams was consulted and made the breakthrough of identifying William’s system as that now famous because of Samuel Pepys, Shelton’s tachygraphy (Sams, 1979). This built on earlier English systems in the Elizabethan and early-Stuart periods.

Shelton’s alphabet (Ryhanen [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)] from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/1f/Shelton-shorthand-alphabet.png)

Unlike a modern shorthand system like Pitman’s, Shelton’s was only partially phonetic. It provided a set of about 300 symbols plus rules for omitting unnecessary letters from words that allowed for the written text to be set down in a heavily abbreviated form. Vowels could be elided by placing a second consonant in one of five different positions relative to a first (a rough equivalent in normal lettering might have pt as pet and pt as pot). This probably had severe limitations as a means of reporting speech verbatim, as William employed it at Putney and on Charles I’s scaffold, rather than of text compression. However, it had a major advantage: it was indecipherable to the uninitiated reader, especially when the system was personalised (William’s shorthand is markedly different from Pepys’).

After Sams had found the basic key to the shorthand material it therefore took years of painstaking work on the part of Frances Henderson to unlock fully what had been there – unread probably since the 1660s. This proved to be around 230,000 words! The contents fall into three main categories: “administration of the army in Scotland during the 1650s”; “a smaller collection of Clarke’s own personal letters and memoranda”; lastly, already published in a new Camden volume, the “more than 400 documents, relating to [English and some European] political military intelligence” (Henderson, 2005, p. 3). These “copies of London newsletters” must be taken in combination with William’s “vast collection of printed newsbooks and pamphlets” as evidence for how well informed William – and army headquarters in Scotland – were (Henderson, 2005, p. 5).

From volume 26 of the Clarke manuscripts covering 1654, mentioned above, Henderson adds 94 pages of material to the mere eight included in Firth (Henderson, 2005, pages 135-229; Firth, 1899A, pages 10-17; Firth 1899B, pages 72-3). This is perhaps an extreme case, but it nonetheless illustrates the extent to which only now – thanks to years of hard labour at the coal face of history by Dr Henderson – the full scope of the Clarke papers is becoming clear. Overall, the shorthand notes in the Clarke papers do not contain a sensational discovery like that of the Putney debates by Pottinger and Firth, however – as Henderson observes – the cumulative gains are important, especially because William was so close to General Monck – who would play such a crucial role in restoring the British monarchies (Henderson, 2005, p. 5).

This ties neatly with the extracts from the Clarke manuscripts included here: information about the death of Oliver Cromwell, which led to the political crisis that culminated in the return of Charles II from exile.

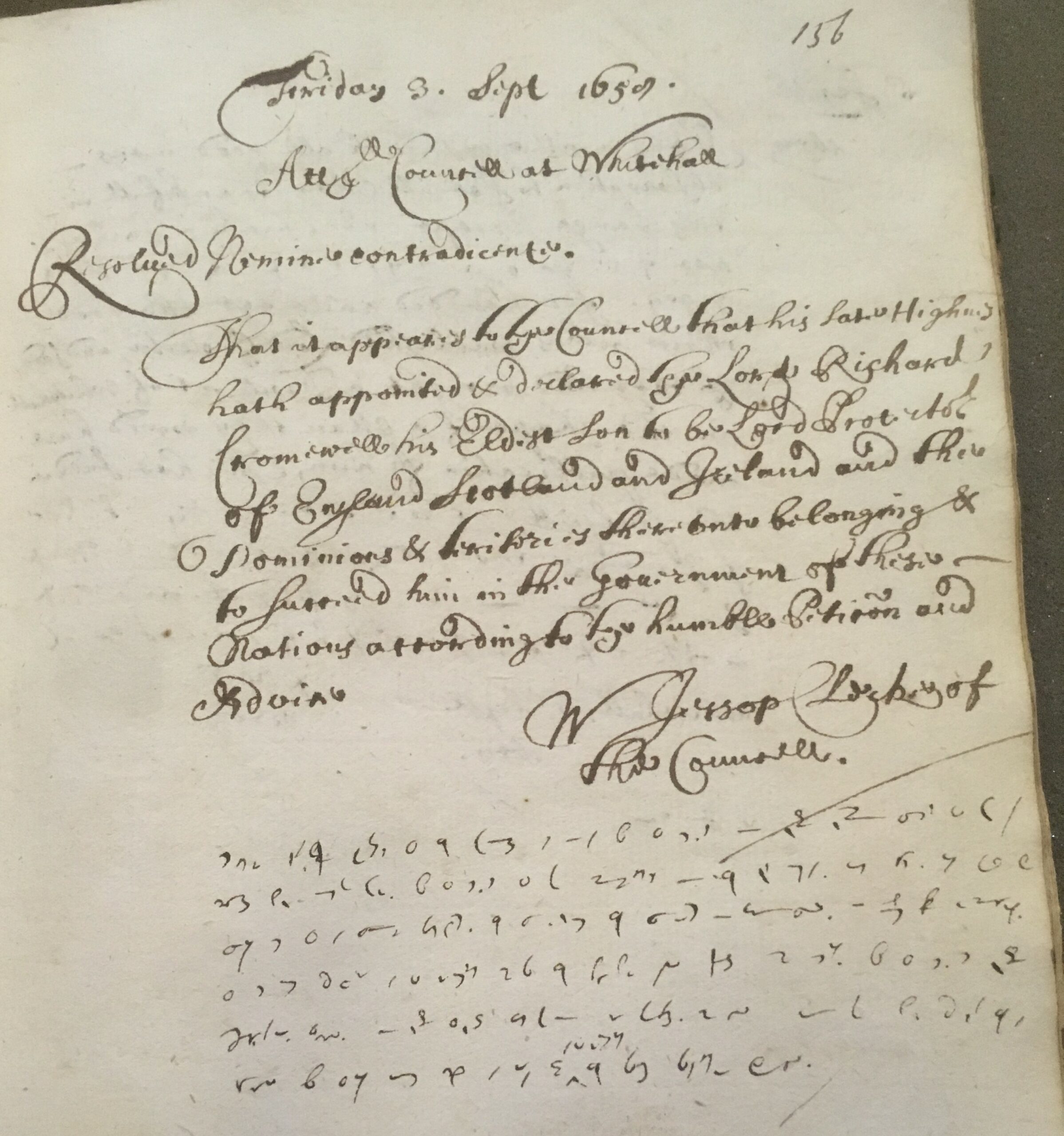

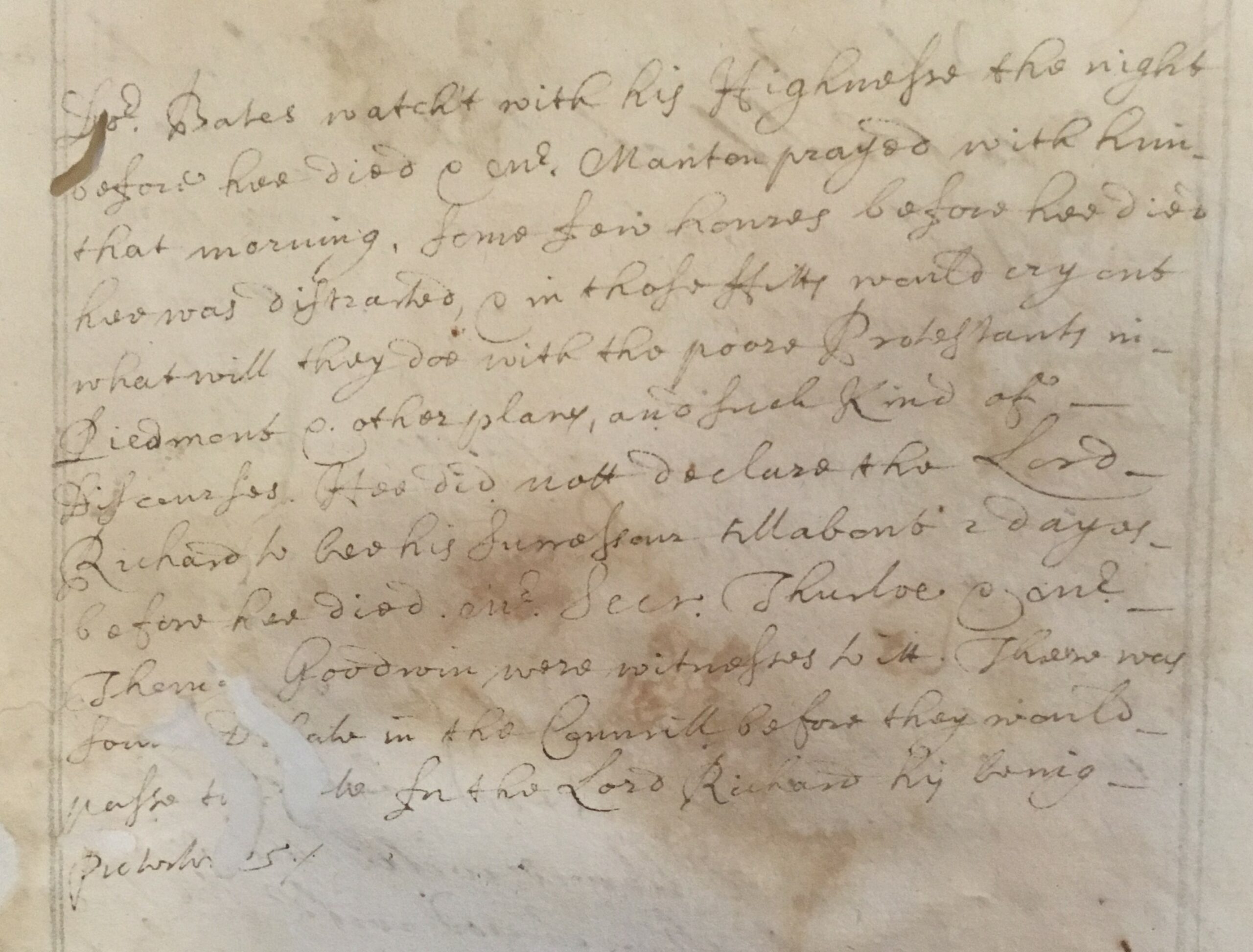

Entries in the Clarke papers for 3 Sept. 1658 in longhand and shorthand (Worcester MS XXX, folio 156r)

Longhand version of the shorthand text for 3 Sept. 1658 (Worcester College MS CLXXXI, folio 413v)

The shorthand portion of the text has been transcribed by Dr Henderson:

Newsletter from London, [3 September 1658]

Dr Bates watched with his Highness the night before he died and Master Manton prayed with him that morning. Some few hours before he died he was distracted and in those fits would cry out, “What will they do with the poor Protestants in Piedmont, in Poland and others places?” and such kind of discourses. He did not declare the Lord Richard to be his successor till about 2 days before he died. Master Secretary Thurloe and Master Thomas Goodwin were witnesses to it. There was some debate in the Council before they would pass the vote for <the Lord Richard> his being Protector etc. (Henderson, 2005, p. 272)

It was the failure of this plan for the succession, with Richard unable as a politician to fill the void left by his father’s death, that ultimately resulted in the Stuart Restoration.

In the longhand version of this extract the reference to Poland is omitted, slightly diluting the sentiments in favour of persecuted Protestants on the continent. Those sentiments reflect Cromwell’s preoccupation with liberty of conscience in matters of religion, often in England at variance with the powerful Presbyterian party. Many mainstream Protestants were unsympathetic towards non-Trinitarians, such as the Polish Brethren – who were expelled from Poland by the Sejm in July 1658 during the Second North War ostensibly as collaborators with Protestant Sweden. The reference to the Duke of Savoy’s massacres in Piedmont of Waldensians (a medieval group that predated the Reformation but had been absorbed by the Protestant movement) may attest to doubts in the Lord Protector’s mind about his own foreign policy. The Duke was a “creature of the French government” with which Cromwell had made an alliance, in part because France – unlike Spain – tolerated Protestants (Morrill, 2004/15).

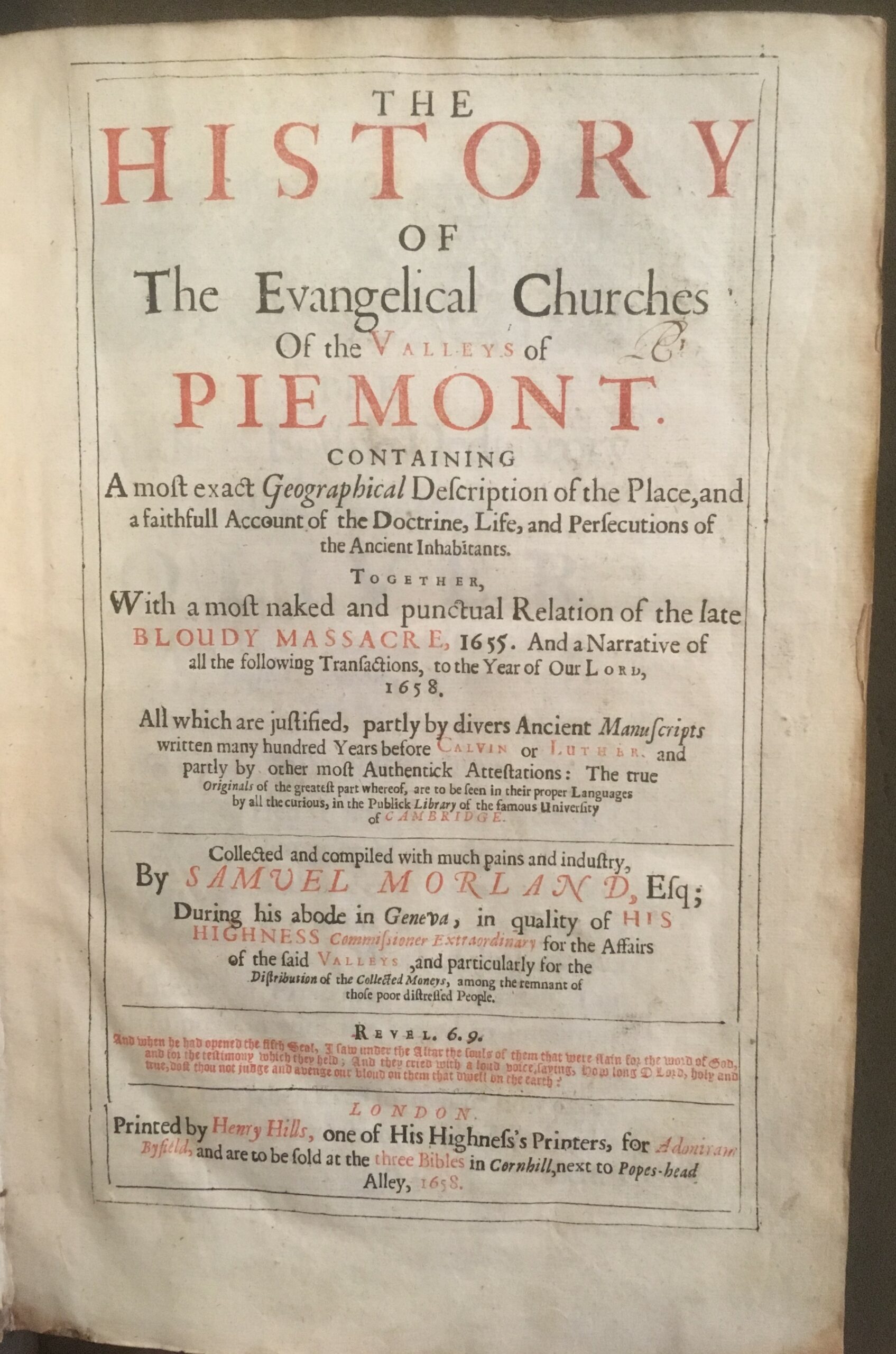

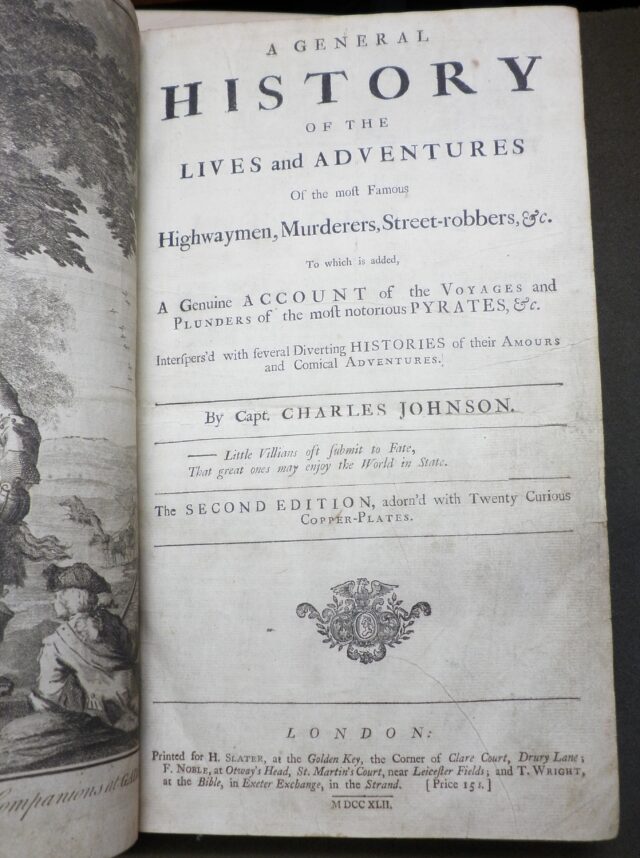

Worcester holds printed matter relating to the situations in both Piedmont and Poland. The exact provenance of the most substantial is unclear. This is a 700-page folio volume, The history of the evangelical churches of the valleys of Piemont by Samuel Morland – a volume dedicated to Oliver Cromwell.

It is certain that this history came to the library from George Clarke, as it bears his monogram on the title page. However, there is another name – Dr Goodwyn – on a fly leaf, so it seems that someone else owned it before George, perhaps making it more likely that he bought it himself rather than having inherited it from Sir William. If so, it might seem a curious purchase for a moderate Tory, and one might speculate – a little too freely probably – that he was trying to illuminate themes in his father’s library. This may stretch a point, and it is not impossible that the book was owned by George’s stepfather, Samuel Barrow, but in the absence of direct evidence a definitive explanation of its provenance remains elusive.

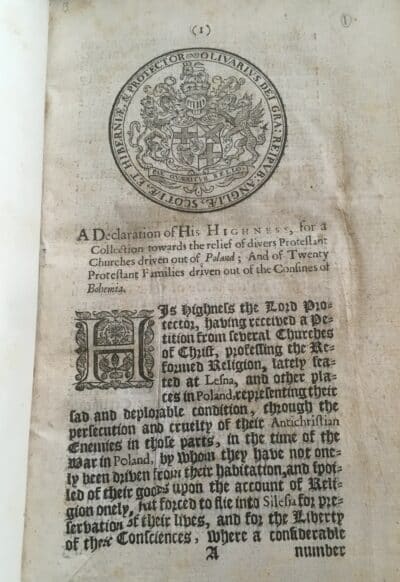

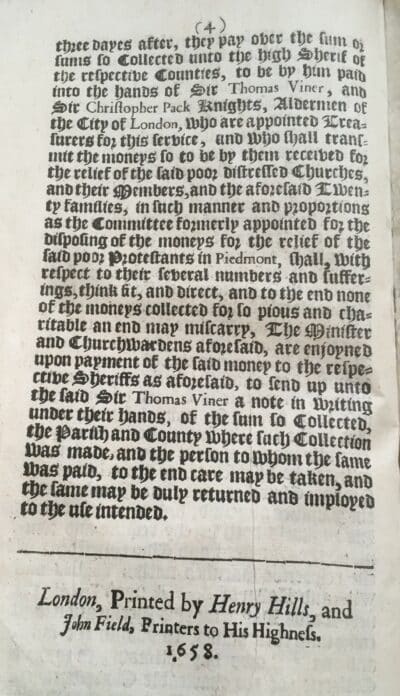

Interestingly, given the reception history of Sir William’s papers, the two shorter items come from both Sir William and C.H. Firth. From the latter Worcester received a declaration by the Lord Protector promulgating a collection for the support of the Polish Brethren.

Amongst the Clarke pamphlets is one issued By the Committee for the Affairs of the poor Protestants in the valleys of Piedmont.

Its second half deals with the fate of the Polish Brethren as well.

This is a neat illustration of the way in which as a continuum William’s pamphlets and manuscripts – especially now that the full scope of the latter is being revealed thanks to Frances Henderson – represent together a scholarly resource of real significance. For the historian of Civil War and Interregnum in both England and Scotland, Worcester Library is home to rich treasures indeed – the extent of which is only now becoming fully known.

Ben Arnold, Assistant Librarian with thanks to Dr Frances Henderson

Bibliography

- Aylmer, G. E. (ed.), Sir William Clarke manuscripts, 1640-1664 (Brighton, 1979).

- Clayton, T., “Clarke, George (1661–1736)”, Oxford dictionary of national biography (Oxford, 2004). https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/5496

- Cromwell, O. (Lord Protector), A declaration of His Highness, for a collection towards the relief of divers Protestant churches driven out of Poland; and of twenty Protestant families driven out of the confines of Bohemia (London, 1658). http://estc.bl.uk/R208230

- Courtney, W. P., “Clarke, George (1660-1736)”, Dictionary of national biography. Volume 10 (London, 1885-1900), pages 448.

- Firth, C. H. (ed.), The Clarke papers: selections from the papers of William Clarke. Volume III (London, 1899A).

- Firth, C. H. (ed.), Scotland and the protectorate (Edinburgh, 1899B)

- Firth, C.H. (ed.), The Clarke papers: selections from the papers of William Clarke, edited by C.H. Firth. Volumes I-II (London, 1992, originally published 1891-1894).

- Goodwin, G., “Clarke, Sir William (1623?-1666), Dictionary of national biography. Volume 10 (London, 1885-1900), page 448.

- Heath, J., The history of the life and death of Oliver Cromwell the late usurper, and pretended protector of England (London, 1663). http://estc.bl.uk/R28052

- Henderson, F., “The hidden hand of William Clarke”, Worcester College record (1998).

- Henderson, F., “Reading, and writing, the text of the Putney debates”, in M. Mendle, The Putney debates of 1647 (Cambridge, 2001).

- Henderson, F., “Clarke, Sir William (1623/4-1666)”, Oxford dictionary of national biography (Oxford, 2004/8). https://doi.org/10/1093/ref:odnb/5536

- Henderson, F. (ed.), The Clarke papers: further selections from the papers of William Clarke. Camden fifth series, volume 27 (London, 2005).

- Le Claire, L., “The survival of the manuscript”, in M. Mendle, The Putney debates of 1647 (Cambridge, 2001).

- Matthews, W., “Introduction”, in T. Shelton, A tutor to tachygraphy, or, Short-writing (1642); Tachygraphy (1647) (Los Angeles, 1970).

- Mendle, M., “Introduction”, in M. Mendle, The Putney debates of 1647 (Cambridge, 2001).

- Morland, S., The history of the evangelical churches of the valleys of Piemont (London, 1658). http://estc.bl.uk/R24410

- Morrill, J., “Cromwell, Oliver (1599-1658)”, Oxford dictionary of national biography (Oxford, 2004/15). https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/6765

- Roots, I., “Firth, Sir Charles Harding”, Oxford dictionary of national biography (Oxford, 2004): https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/33137

- Sams, E., “Sir William Clarke’s shorthand”, in G.E. Aylmer (ed.), Sir William Clarke manuscripts, 1640-1664 (Brighton, 1979).

- Shelton, T., A tutor to tachygraphy, or, Short-writing (1642); Tachygraphy (1647) (Los Angeles, 1970).

- Trevor, S., By the Committee for the Affairs of the poor Protestants in the valleys of Piedmont (London, 1658) http://estc.bl.uk/R208249

- Woolrych, A. (1992), “Preface”, in The Clarke papers: selections from the papers of William Clarke, edited by C.H. Firth. Volumes I-II (London, 1992, originally published 1891-1894).