Tales by the Yule Log Fire

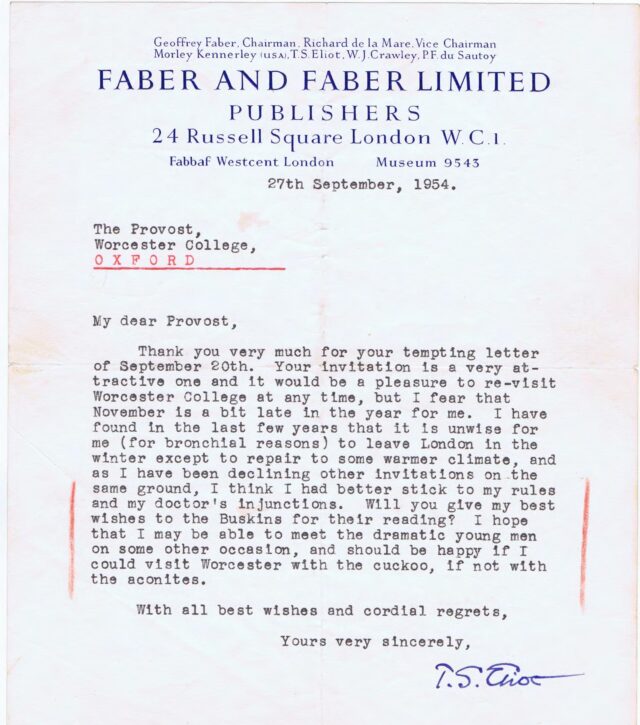

15th December 2017

Tales by the Yule Log Fire

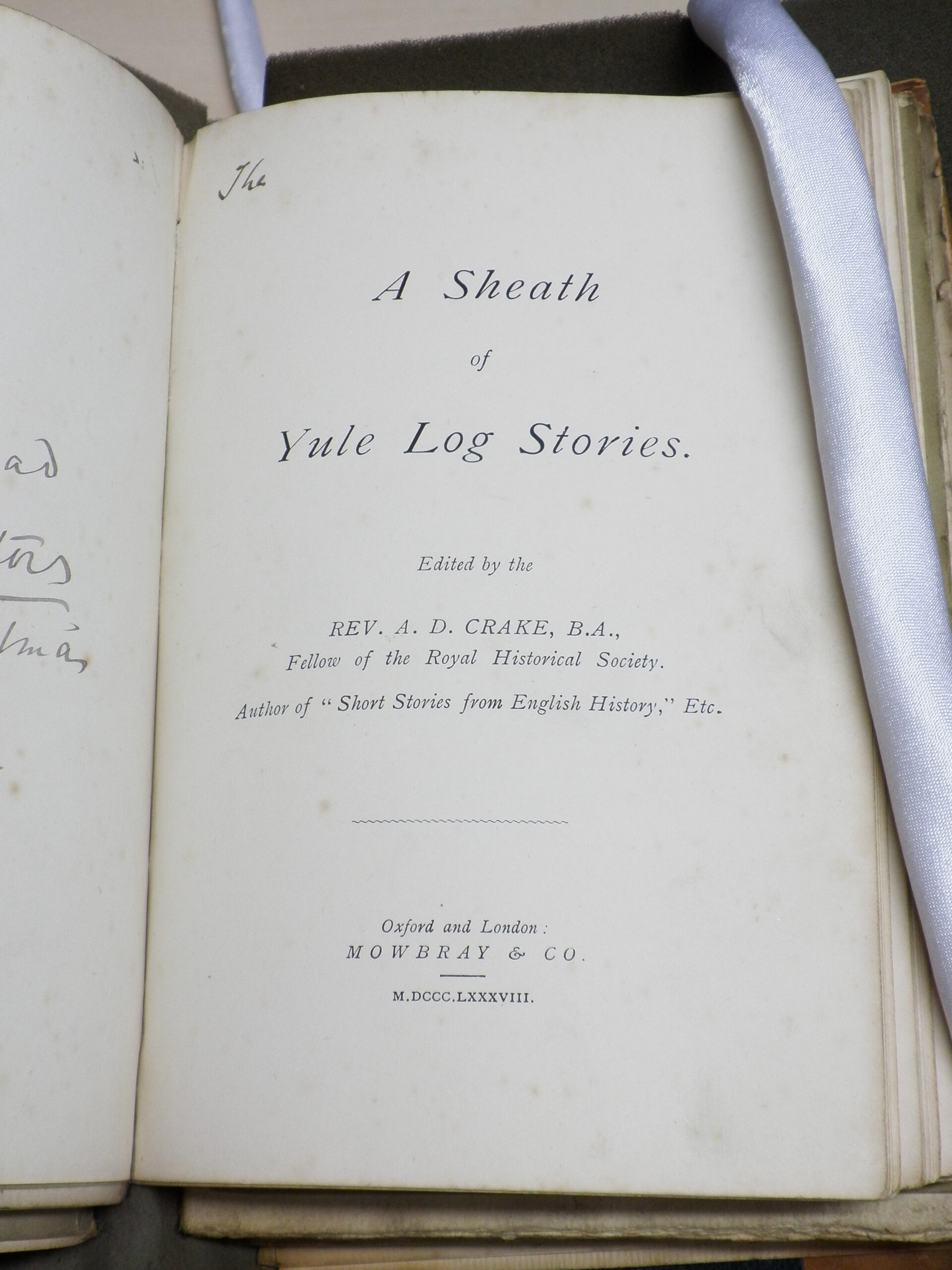

A Sheath of Yule Log Stories, Edited by the Rev. A. D. Crake, B.A., Fellow of the Royal Historical Society.

Oxford and London : Mowbray & Co., M.DCCCLXXXVIII.

For the end of the year, we have a Christmas treat: A Sheath of Yule Log Stories was published in 1888 by the Rev. Augustine Crake (1836-1890), a schoolmaster and clergyman best known for his works of history for children. Crake was an Oxfordshire native, born in Chalgrove, and worked as a schoolmaster at All Saints School in Bloxham, among other places, before settling eventually as a vicar in Berkshire (Seccombe, ‘Crake, Augustine David (1836-1890)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography). He was married to Annie Lucas, daughter of John Lucas, who worked for many years as an assistant in the Radcliffe Observatory in Oxford (Seccombe, ODNB; Burley and Plenderleith, A History of the Radcliffe Observatory Oxford, pp. 79-82).

Crake’s Yule Log Stories is a collection of tales told to him by friends and relations during childhood Christmas visits to the Lake District. In the preface he assures readers that only two of the stories are original and that the others ‘are nearly all founded upon facts, real or supposed, related to me by different individuals’.

There are no illustrations, but each chapter begins with a small woodcut decoration and capital.

The collection is introduced with a nostalgic description of the lakes and the remote farm house where young Crake spent his Christmas.

‘Oh how my heart beat with joy when I saw the Pillar mountain, and Red Pike in the distance, what visions of skating and sledging by day, and glorious evenings around the cheerful fire, in the huge cavernous chimney-place, where I generally contrived to get one of the corners, watching the snow flakes, hissing as they fell from the darkness above, into the cheerful flames.’ (p.3)

‘Preparing for Christmas Eve’ by H Garland, The Illustrated London News, 19 December 1868 (p. 589)

Each chapter begins with brief descriptions of days spent skating and sledging, playing games, and attending Christmas services, before settling down to the serious business of the evening story by the fire. The collection has the feel of a children’s storybook but Crake’s stories are not for the faint of heart – ghosts, robbers, and murderers dominate the tales told by grandparents, uncles, and visiting friends. In his preface Crake writes:

‘These particular stories lie on the border land between the seen and unseen ; they may be very incredible ; but they will serve to pass away the happy time around the Yule Log, when mythic stories are most acceptable.’

The stories range from local ghosts and legends to a Wild West tale from a Canadian cousin and a dramatic military escapade from a French schoolmaster. Grandfather and grandmother tell the first two stories of lucky escapes from robbers. While out hunting on Christmas Eve, grandfather lost his way in a snowstorm and had nearly given up hope when…

‘…I saw – a light! I hurried towards it, my strength renewed by hope; I crossed ravines, half choked with snow; I emerged on the open moor. Yes, it was the light from a window, but what window? Now I was close: why, it was a Gothic window – a kind of church window; how came it there on the moor? Now I saw through it all, it was the abbey – the old ruined abbey – raising its form in the darkness before me…’ (p. 12)

He remembered his uncle’s tales of the haunted abbey and proceeded with caution, but found only an empty room with a roaring fire. While warming himself and dozing before the fire, he was awoken by a sound…

‘…It was the sound of solemn music, and it seemed to come from the ruined chapel… I thought that a single voice intoned “Gloria in excelsis Deo,” when the whole choir took up the strain, “pax in terra hominibus bonæ voluntatis,”… I remembered all at once that this was Christmas night, when the monks of old were wont to chant their midnight mass, and a thrill of awe passed through me. Could it be that the spirits of those long departed votaries were permitted to re-enact the scenes of their past worship on earth on this night of nights?’ (p. 14)

He went to investigate, which was fortunate because as soon as he was out of sight, the earthly inhabitants of the ruined abbey, ‘six foul midnight assassins’, returned. After becoming aware of grandfather’s presence, a deadly pursuit ensued, in which our assassins met rather sticky ends. Grandfather thankfully survived to tell the tale, and marry grandmamma.

Grandmother is not to be outdone and the next night she tells her own tale of a narrow escape at Christmastime. When grandfather was called away to visit his sick sister, she was left alone, but for the maid, on Christmas Eve. As night fell, old Martin’s big black dog, ‘that ugly Rover’, appeared at the house and demanded to be let in. The women admitted him, but after a quiet evening by the fire…

‘…It was now time to go up to bed, and we lit our bedroom candles, when, to our astonishment, Rover manifested a great disapprobation of our proceedings, barked, whined, pulled at our dresses, and in every way a dog could, signified his pleasure that we should stay down stairs.’ (p. 29)

The women eventually went to bed but were woken in the night by growling and the sounds of a scuffle…

‘We both sprang out of the bed and hurried to the window, whence we saw two men dragging a third by the legs out of the casement of the scullery… while from time to time he uttered stifled groans mingled with curses. They tore him away from the dog, which seemed to have him by the throat…’ (p. 32)

They went downstairs and discovered a knife dropped by the intruders, making clear that their visit was not a friendly one, and the dog had saved them from a terrible fate.

‘But how did the dog know? Who sent him? No man can answer that question. Martin only knew of his absence; but I doubt not WHO it was.’ (p. 34)

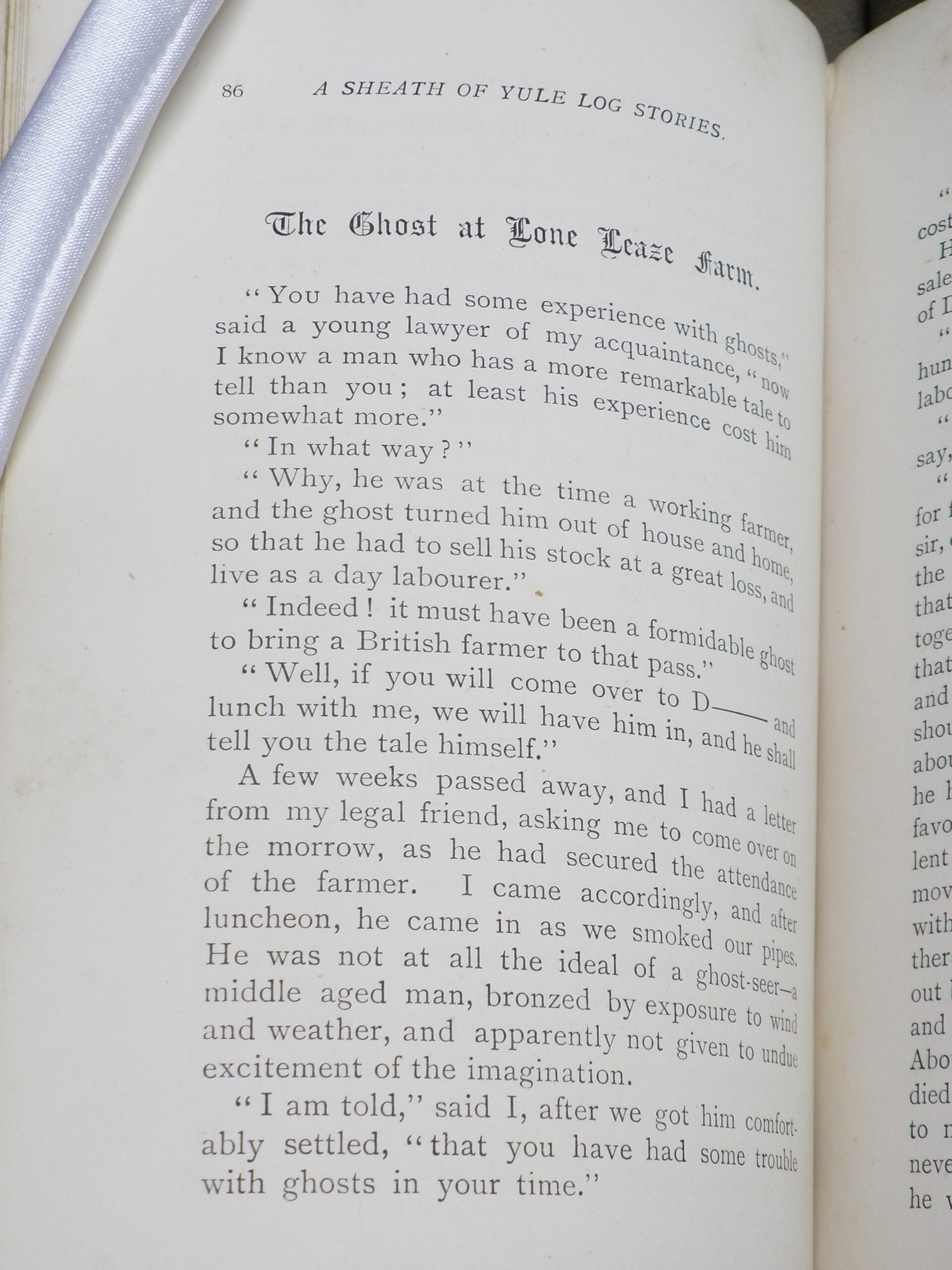

Alongside these tales of adventure and gentle supernatural aid are more sinister ghost stories (which were not necessarily set at Christmastime). An uncle tells of a terrifying visitation from a ghost of a woman who murdered her own children; a cousin shares a family legend of a witch who curses the children of the family; another cousin tells the story of a haunted farm nearby; and in the final story of the volume, the parson shares a story of a priest who is visited by the skeletal ghost of a monk seeking absolution. The audience does not shy from these tales of terror – indeed they demand them:

‘“Let it be about ghosts,” – and a pleasant shiver ran around, for we liked a tale of diablerie best of all.’ (p. 75)

The children in Crake’s stories were hardly alone in demanding a ghost story at Christmas. An oral tradition of telling ghost stories at Christmas dates back at least to the eighteenth-century, but it was the Victorians who really established the Christmas ghost story in print (Moore, Victorian Christmas in Print, p. 82). Charles Dickens is of course the most famous Victorian writer of supernatural Christmas tales and though his were not the first Christmas ghost stories, his influence on the development of the genre was substantial. Following the publication of A Christmas Carol in 1843, there was a proliferation of ghosts in the expanding market of Christmas gift books (Moore, Victorian Christmas, p. 82; for more see Moore, Victorian Christmas in Print, chapter 4). Crake’s book is typical of Victorian Christmas books in that the tales are presented using a ‘frame story’ – a technique where the author creates a setting for storytelling, in this case the young Crake visiting family in the Lake District, and then presents various tales within that setting. The frame story was a way of adapting the traditions of oral storytelling to print and allowed the reader to feel a part of the traditional storytelling circle (Moore, Victorian Christmas, p. 85).

‘Christmas Eve – putting up the holly and mistletoe’, The Illustrated London News, 22 December 1855 (p. 721)

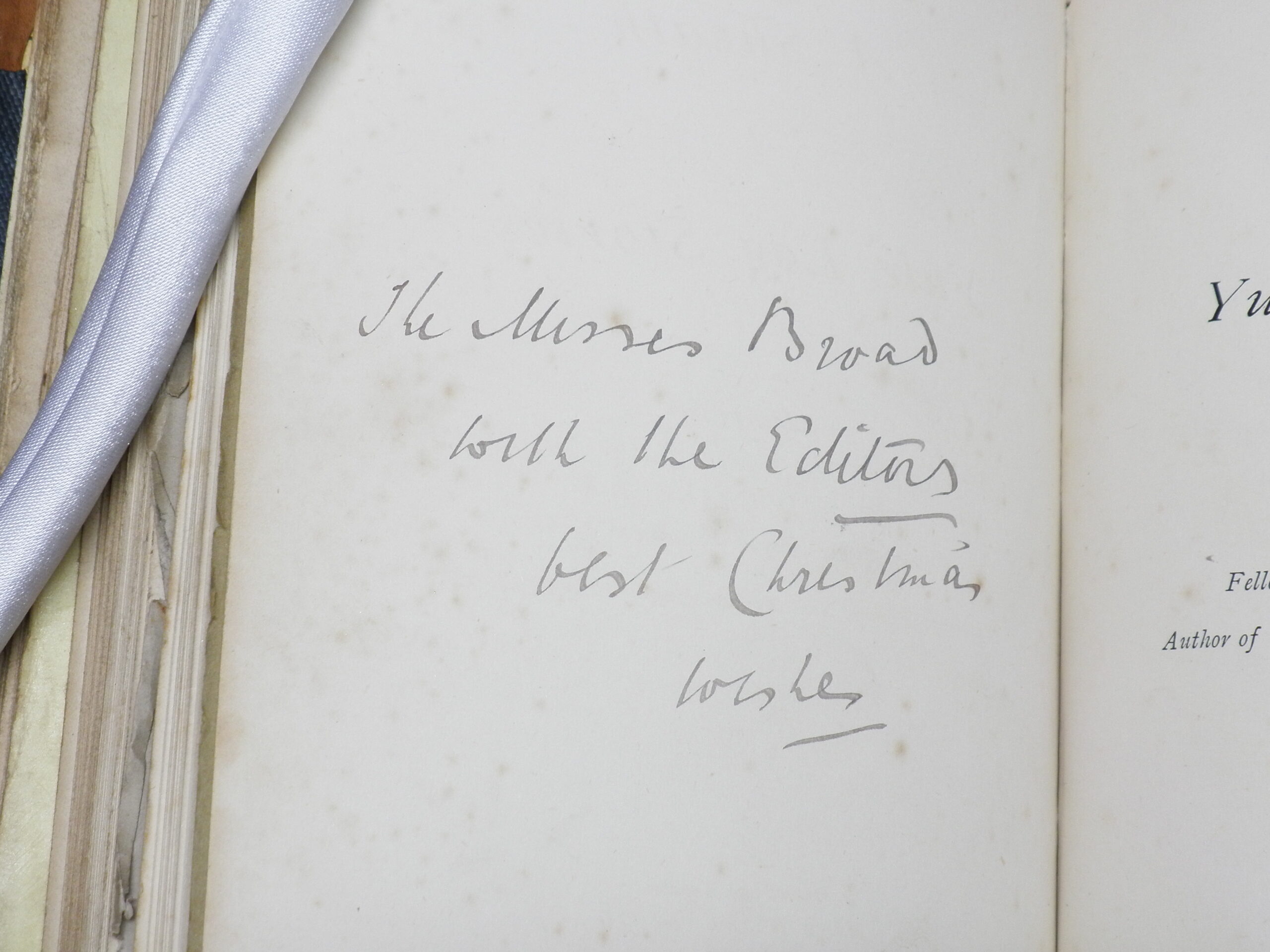

Like many of our interesting nineteenth-century pamphlets, our copy of Yule Log Stories likely came to the library from the collection of Henry Allison Pottinger (Librarian 1884-1911), who was known for his eclectic collecting habits. From an inscription opposite the title page we can see that it was given as a gift from the author himself.

We don’t know who the Misses Broad were – perhaps family or the children of friends – but it is easy to imagine several young girls sat by their own fire at Christmastime, delighting in these tales of adventure and mystery.

‘Christmas Stories’, The Illustrated London News, 24 December 1892 (p. 809)

Renée Prud’Homme, Assistant Librarian

Bibliography

- Burley, Jeffery and Plenderleith, Kristina (eds.), A History of the Radcliffe Observatory Oxford: the Biography of a Building, (Oxford: Green College, 2005)

- Moore, Tara, Victorian Christmas in Print (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009)

- Seccombe, Thomas, ‘Crake, Augustine David (1836-1890)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), accessed 12 December 2017, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/6588