‘So you have the plants of most parts of the world, contained in this garden…’

28th September 2018

‘So you have the plants of most parts of the world, contained in this garden…’

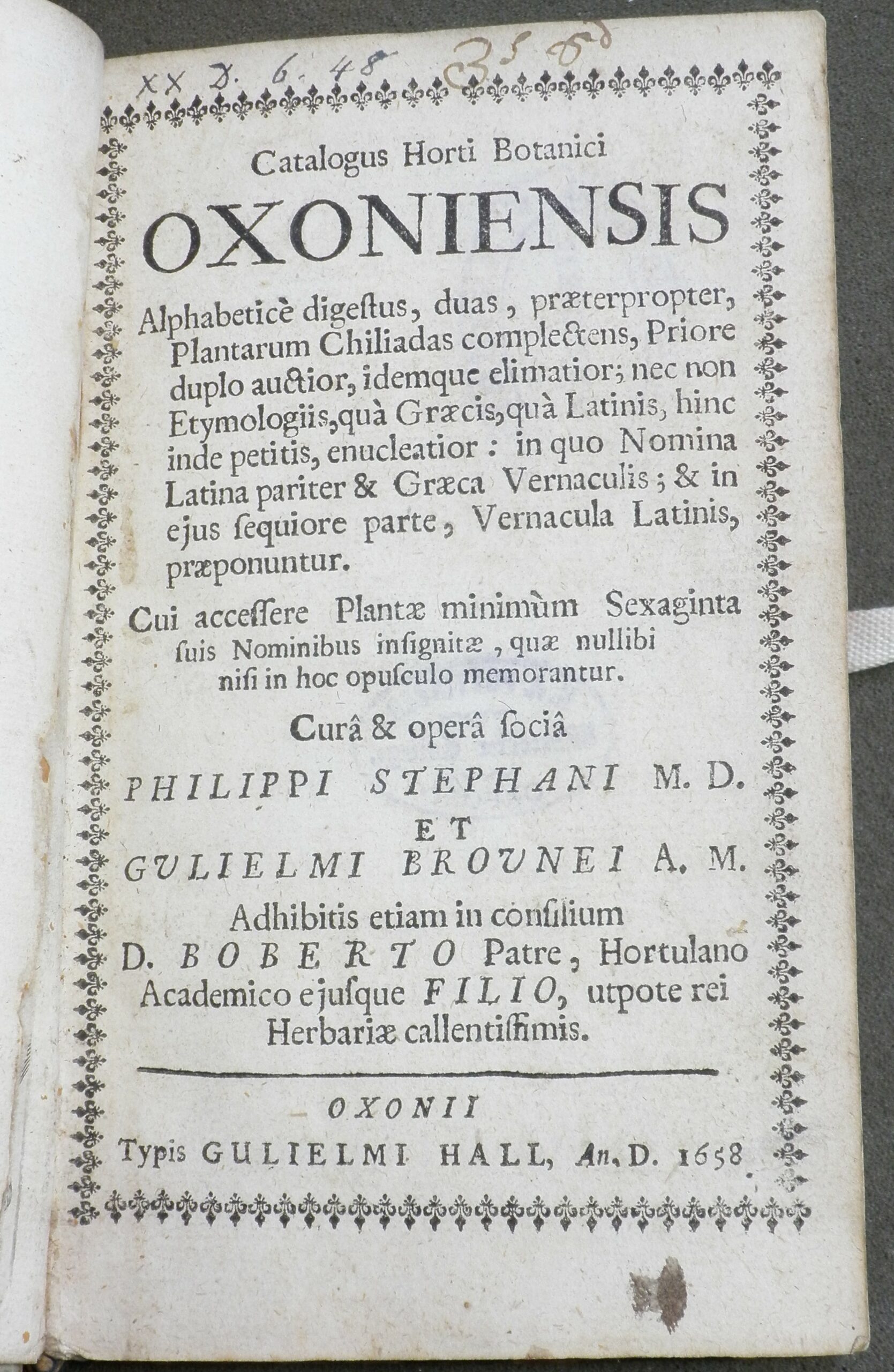

Philip Stephens and William Browne, Catalogus horti botanici Oxoniensis. Oxonii: Typis Gulielmi Hall, 1658

and

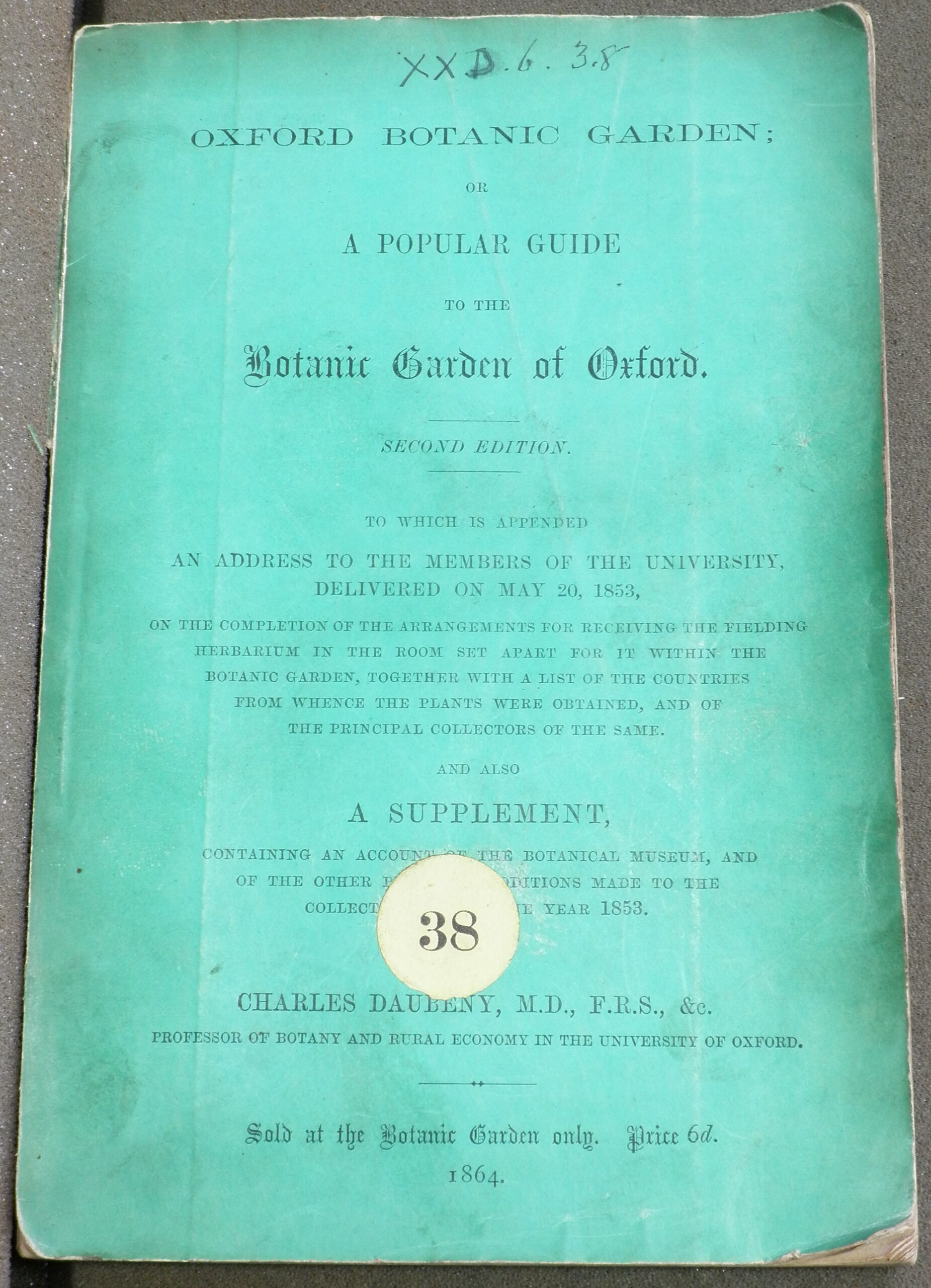

Charles Daubeny, Oxford Botanic Garden, or, A popular guide to the Botanic Garden of Oxford. Oxford : sold at the Botanic Garden only : printed by Messrs. Parker, [1864]

Among the thousands of items left to Worcester College Library by our former Librarian, Henry Allison Pottinger, are numerous books and pamphlets relating to both the city and University of Oxford. This month we are looking at two items from the Pottinger collections related to the Oxford Botanic Garden – a seventeenth-century catalogue of the plants in the Garden and a nineteenth-century popular guide, which show us snapshots of the Garden at very different times in its history.

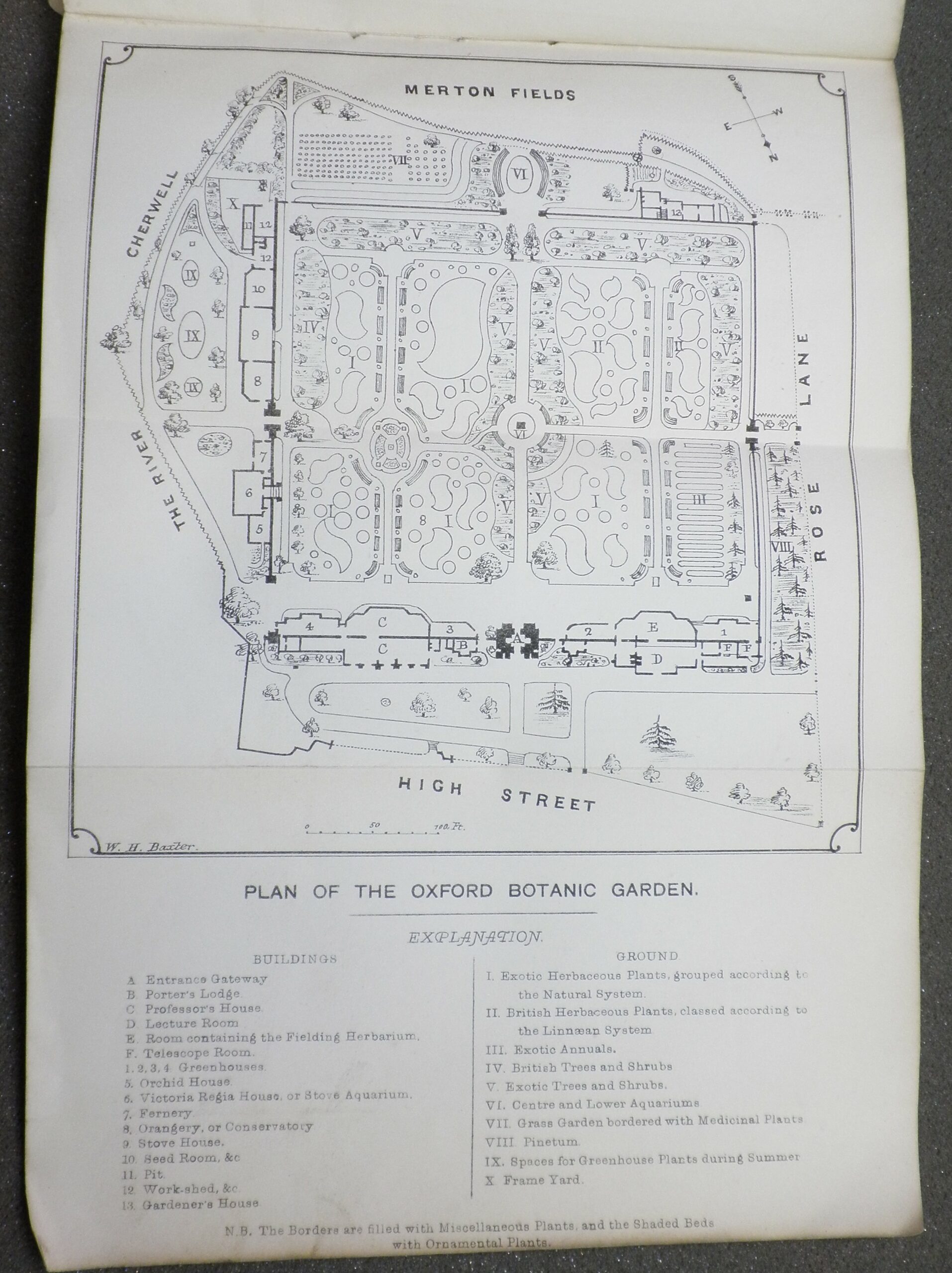

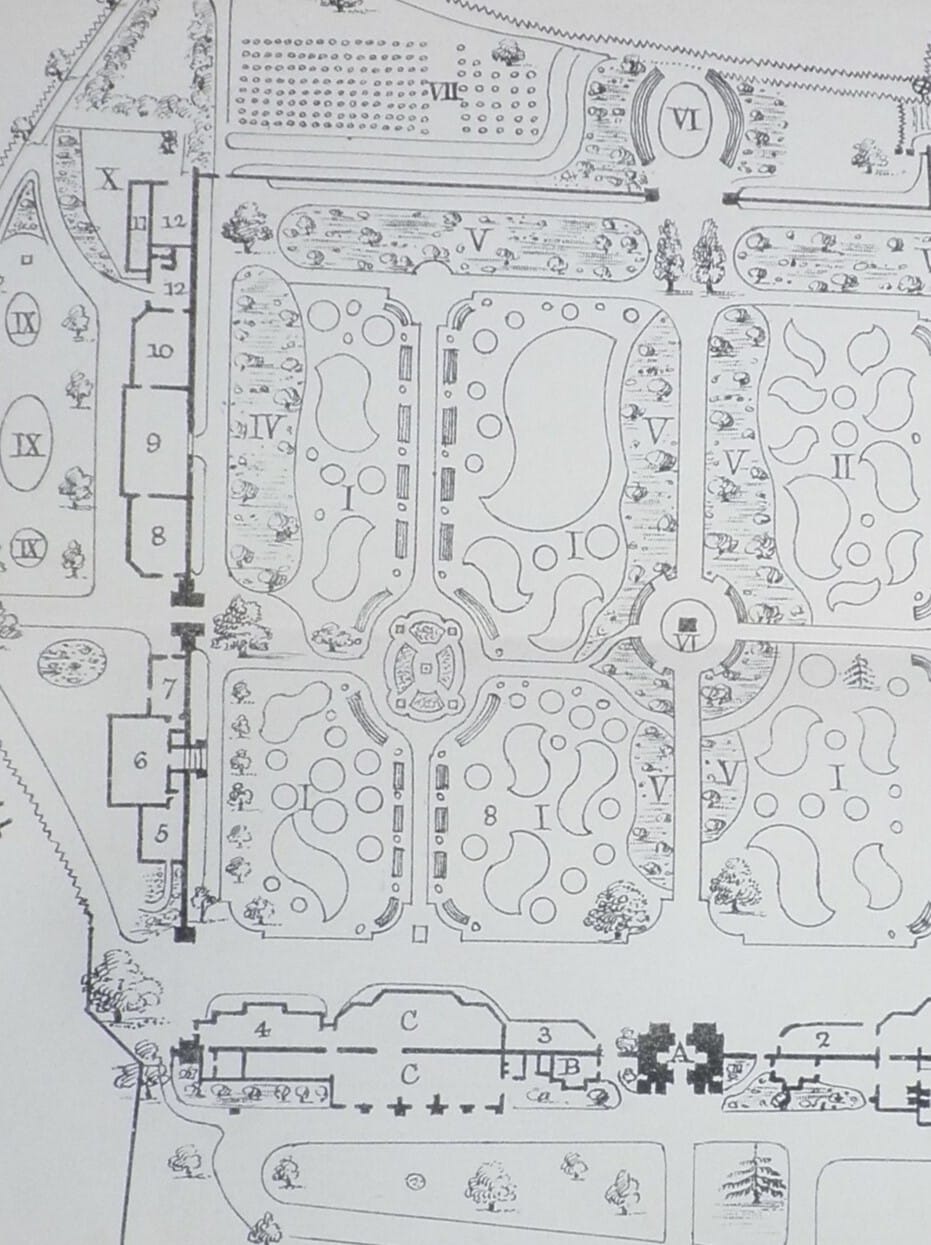

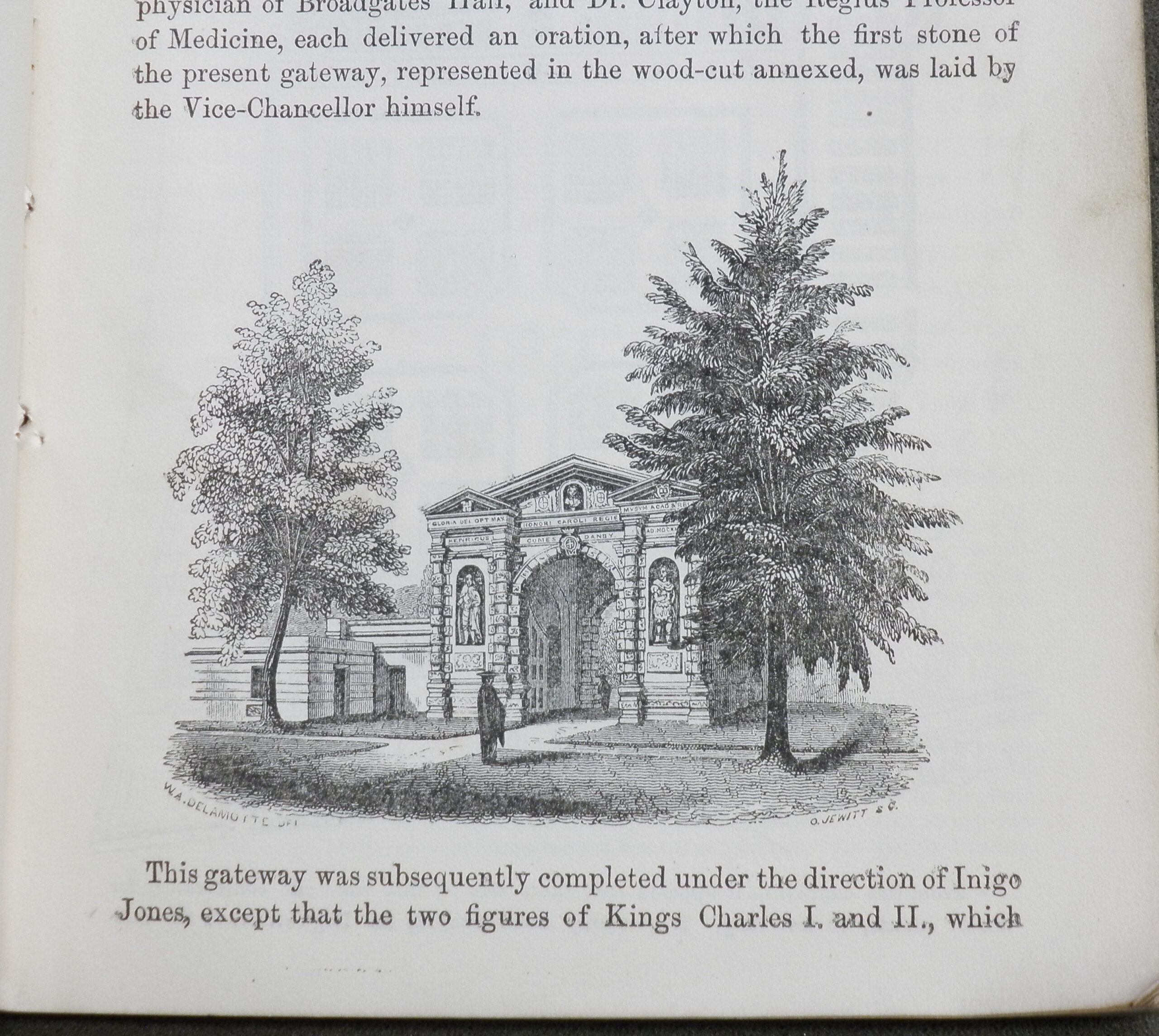

Illustration from Daubeny’s Oxford Botanic Garden.

The Botanic Garden, originally called the Physick Garden, was founded by Henry Danvers, the Earl of Danby, in 1621 and is the oldest surviving botanic garden in Britain (Stephen Harris, Oxford Botanic Garden & Arboretum, p. x, p. 11, p. vii). The Garden was one of a number of botanic gardens founded throughout Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. John Prest attributes this growing interest in creating encyclopaedic, academic gardens in part to the discovery of the Americas, which engendered a desire to accumulate all of the plants of the world into one place to be studied. He argues this was as much a theological as a scientific impulse – a comprehensive botanic garden in imitation of the Garden of Eden could help man to understand God as He was revealed in his creation (Prest, The Garden of Eden, pp. 6-10; see also Prest Chapter IV).

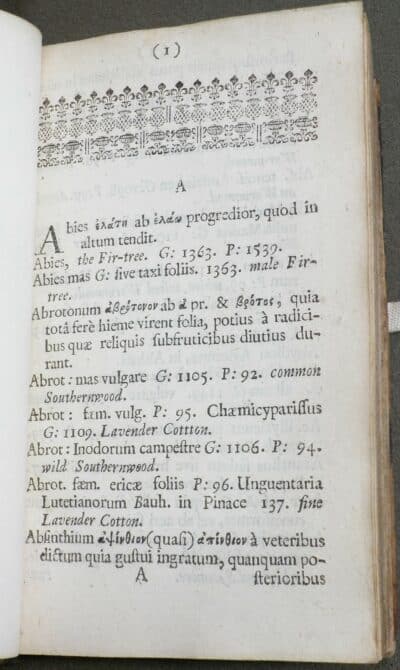

The Catalogus Horti Botanici Oxoniensis of 1658 was compiled by Philip Stephens and William Browne, based on the earlier Catalogus Plantarum Horti Medici Oxoniensis by Jacob Bobart the Elder, Superintendent of the Garden 1642-1679. Dr Stephens was Principal of Magdalen Hall and Browne was a Fellow of Magdalen College (R.T. Gunther, Early British Botanists and their Gardens, pp. 298-299). The catalogue lists Latin and English names, as well as references to the herbals of Gerard and Parkinson, for 1,889 plants in the garden (Gunther p. 299-300; Harris p. 26). There is prefatory material in English, Latin, and Greek, including several poetic dedications celebrating the value of the work, which have been decorated with printers’ ornaments.

One of the reasons for founding botanic, or physick, gardens in this era was medical research. According to Prest, in the early modern era most plants were believed to have medicinal value and by collecting as many of them in one place as possible, physicians could hope to find cures to all ills (Prest, p. 57). This interest is reflected in Stephens and Browne’s catalogue. In the preface to the second part of the catalogue they write

‘We chearfully undertook this work being moved by the solicitations of students in Physick & lovers of plants… being confident it will not be only an ornament but of use also to the true Physician.’

And in his dedicatory poem at the start of the catalogue, R.I. states

‘Your Book is one great Panax and containes

Herbs fit to heale all sores, and cure all paines’

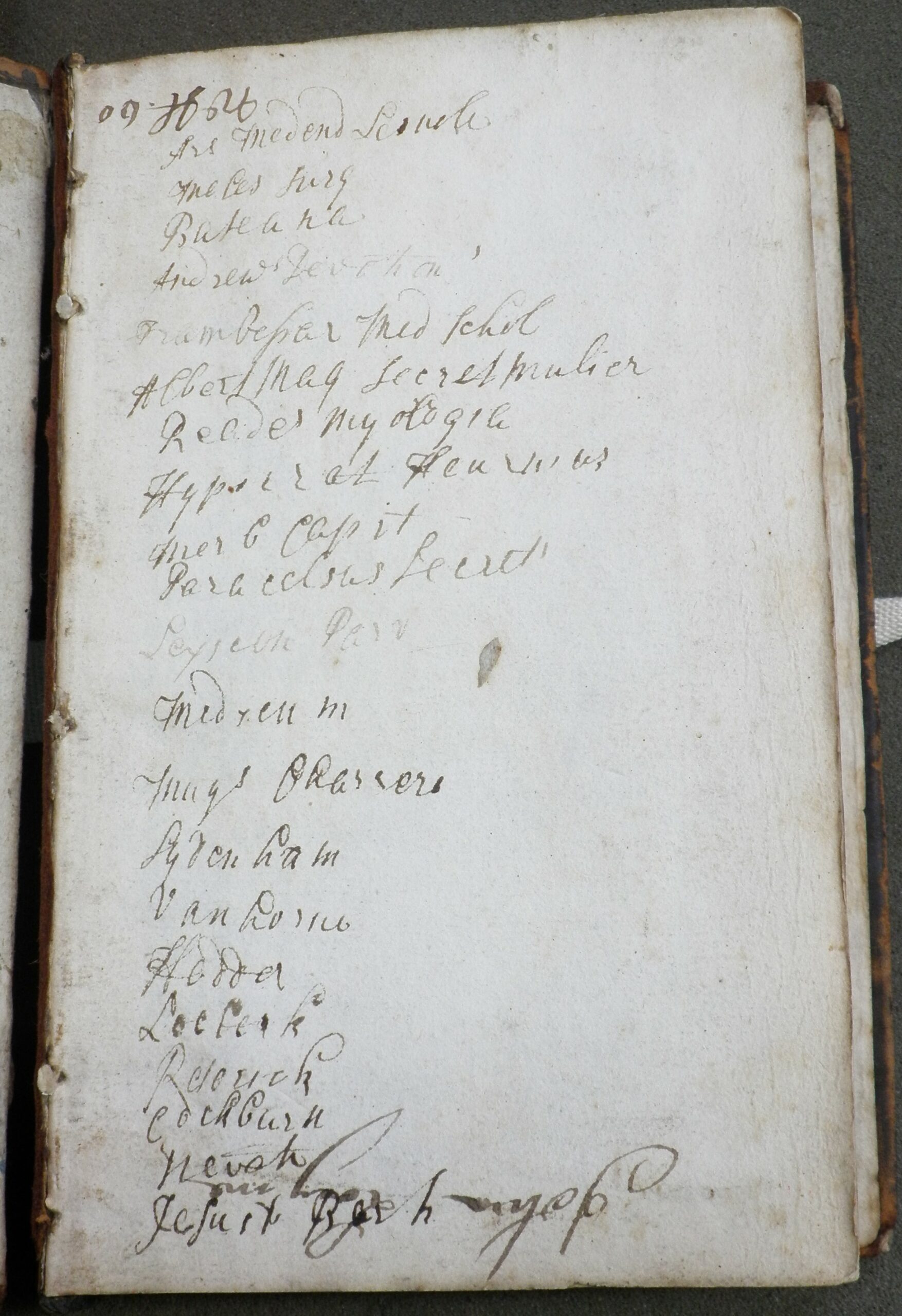

There is also some evidence that our copy might have been owned by a medical student, or at least a reader interested in medicine: the blank flyleaves at the end are inscribed with a handwritten list of medical authors and titles.

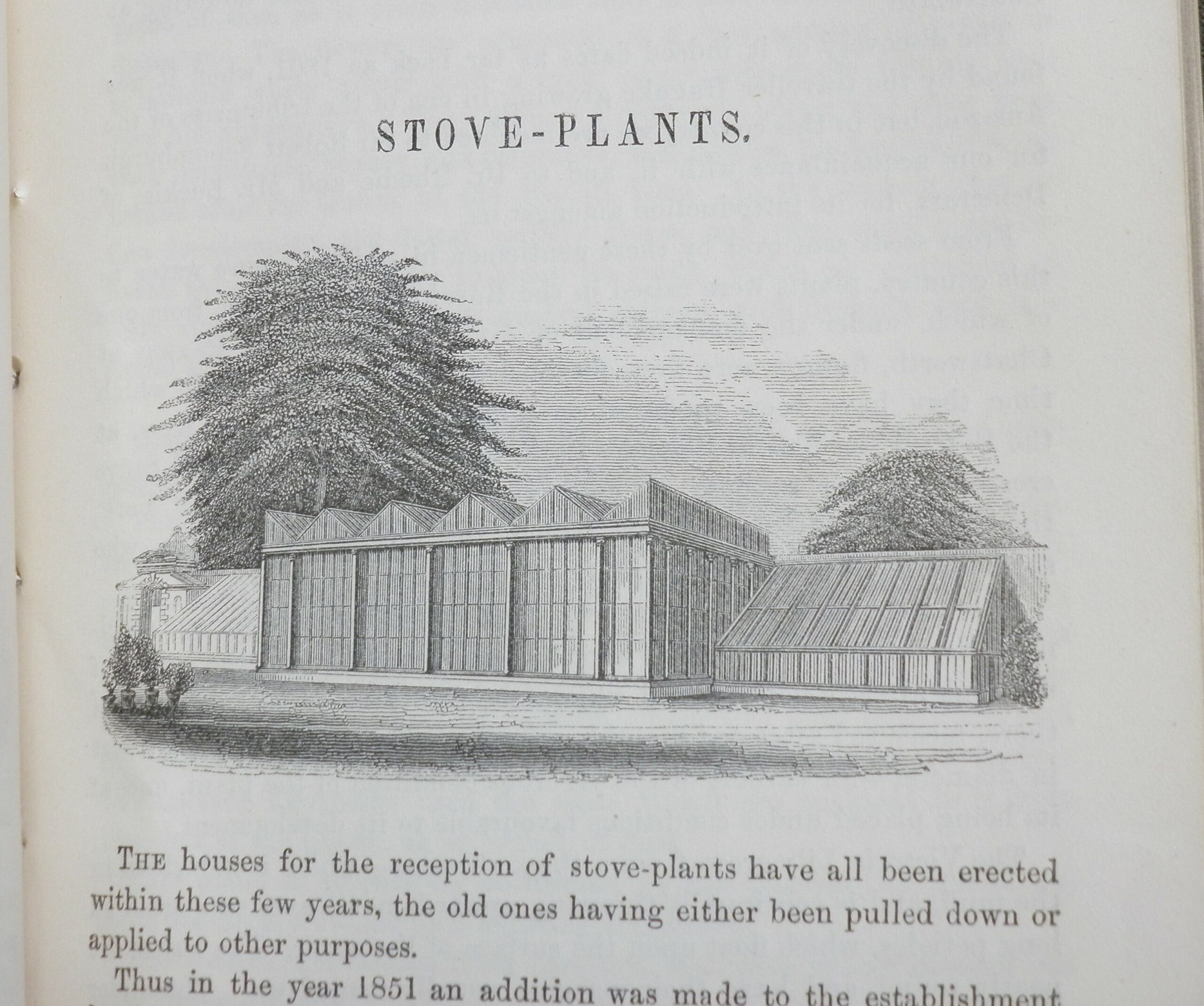

Two centuries later, Charles Daubeny (1795-1867), Sherardian Professor of Botany, wrote a new guide, which demonstrates the changing interests in and attitudes toward the Garden. First published in 1850, the Oxford Botanic Garden: or A Popular Guide to the Botanic Garden of Oxford is a guidebook rather than a catalogue – he seeks only to introduce the different varieties of plants to be found there, rather than to enumerate them.

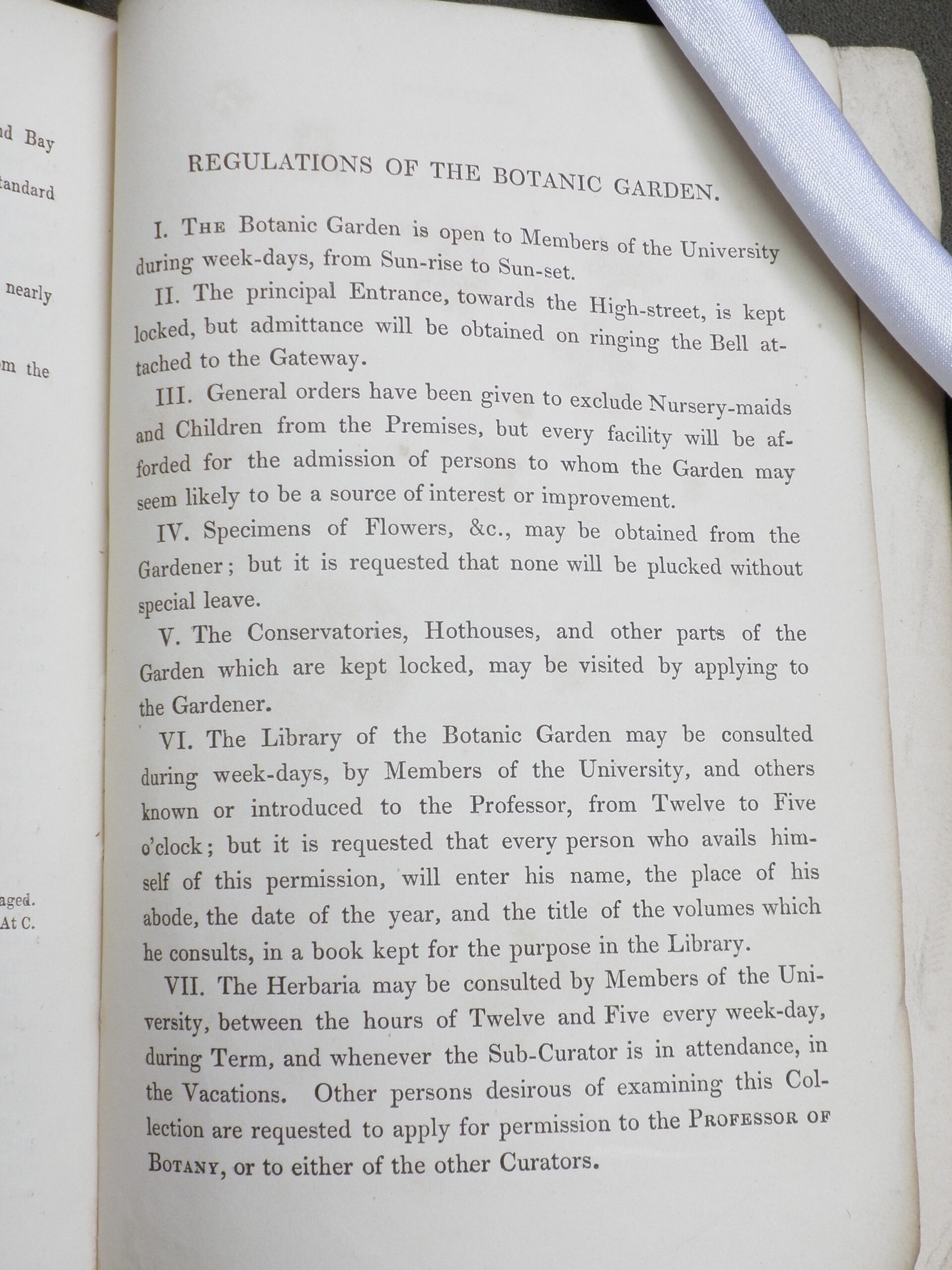

The need for a popular guide shows a changing attitude to public engagement with the Garden. Though the Garden had theoretically been open to the public from early on, Daubeny tried to make the Garden more appealing to visitors and encouraged engagement with city gardening groups. Though his rules, which are listed in the back of the guide, suggest access was still tightly controlled (Harris, pp. 79-80, p. 89).

Another change is in the name itself – after being appointed in 1834, Daubeny began referring to the ‘Physick Garden’ as the ‘Botanic Garden’ instead, which was representative of his desire to encourage the study of botany as an academic subject in its own right, not just as an adjunct to medicine (Harris, pp. 91-92). Improving the quality and status of science education was a lifelong mission of Daubeny’s. His own academic training and research spanned chemistry, geology, medicine, and botany, and he was unusual for his time in choosing to pursue a career as an academic scientist (N. Goddard, ‘Daubeny, Charles Giles Bridle (1795–1867), chemist and botanist’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography). In the second edition of the guide to the Garden, he appends an address made to the members of the University on the acquisition of the Fielding Herbarium, in which he extols the educational opportunities provided by the Herbarium and declares that

‘At all events, the universal feeling which prevails throughout the country at the present day with regard to the Physical Sciences, will I am sure, eventually disabuse the minds of those educated within our walls of an impression too prevalent in the University – namely, that Natural Philosophy is only of importance to members of the Medical Profession – a notion almost as unreasonable with reference to Divines, as is the converse one so common in the world at large, which assumes theological knowledge to be unnecessary for the Laity…’ (pp. 14-15)

Daubeny would certainly be gratified to see the prominent role of the sciences in the University today, as well as the continued use of the Garden for scientific research. Public engagement has also continued to be an important part of the Garden’s mission, though Daubeny may have been pained by not only the admittance, but positive encouragement, of ‘nursery-maids and children’ in the twenty-first century Garden.

Renée Prud’Homme, Assistant Librarian

Illustration from Daubeny, Oxford Botanic Garden.

Bibliography

- Gunther, R.T., Early British Botanists and their Gardens: based on unpublished writings of Goodyer, Tradescant, and others (Oxford, 1922)

- Goddard, N. (2004, September 23). Daubeny, Charles Giles Bridle (1795–1867), chemist and botanist. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Ed. Retrieved 9 Aug. 2018, from http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-7187.

- Harris, Stephen A., Oxford Botanic Garden & Arboretum: A Brief History (Oxford: Bodleian Library, 2017)

- Jackson, B. (2004, September 23). Browne, William (1629/30–1678), botanist. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Ed. Retrieved 9 Aug. 2018, from http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-3707.

- Prest, John, The Garden of Eden: the Botanic Garden and the Re-Creation of Paradise (New Haven: Yale, 1981)