Orange, Lemon, or Citron? Giovanni Battista Ferrari’s Hesperides

29th June 2018

Orange, Lemon, or Citron? Giovanni Battista Ferrari’s Hesperides

Hesperides, sive, De malorum aureorum cultura et usu

Giovanni Battista Ferrari

Rome: Herman Scheus, MDCXLVI [1646]

480 pages, folio

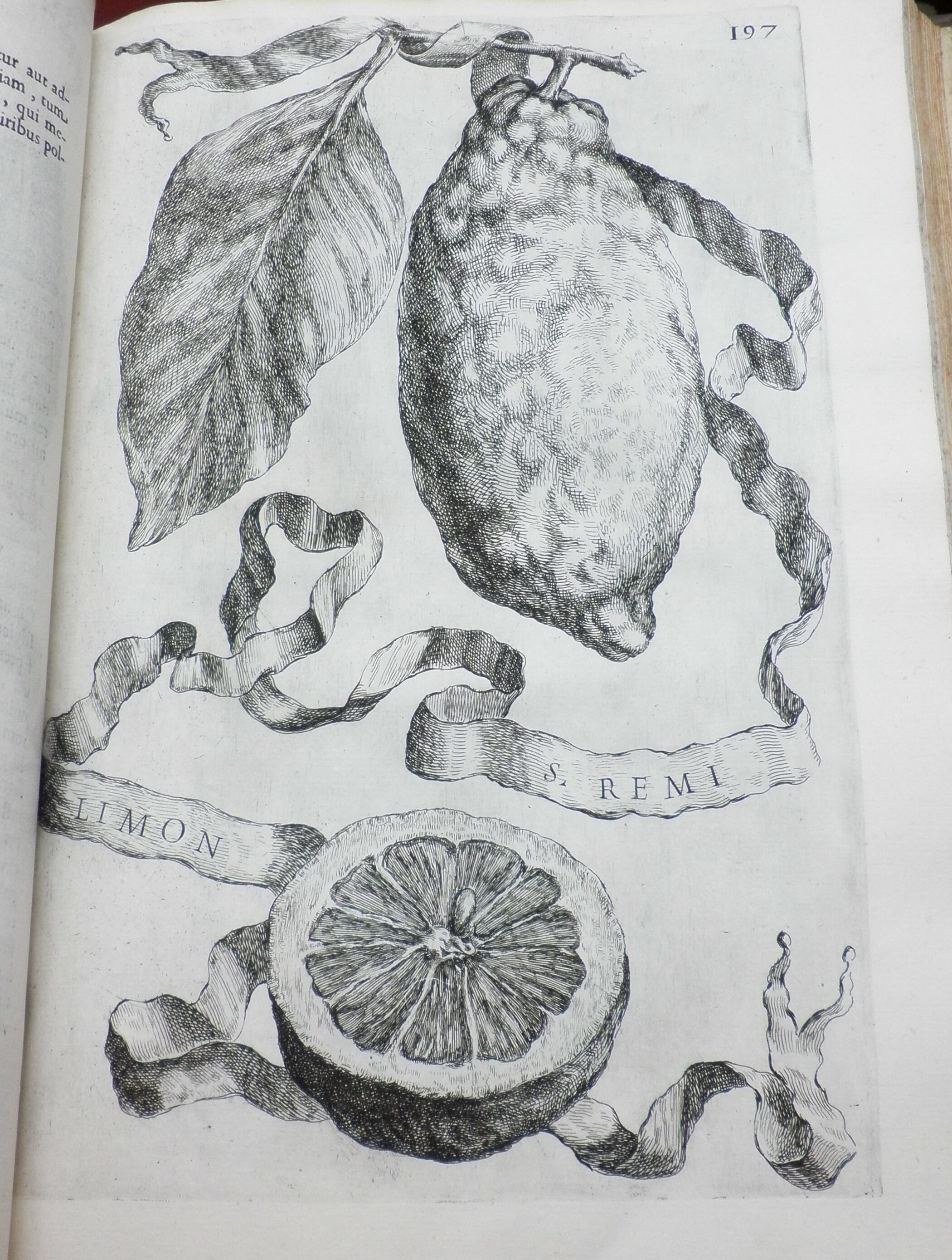

This month’s treasure whisks us away to the seventeenth-century citrus orchards of Italy. Giovanni Battista Ferrari’s Hesperides, sive, De malorum aureorum cultura et usu is a lavishly illustrated folio on citrus fruit, focusing primarily on taxonomy, but also covering history, folklore, cultivation, and culinary use.

Ferrari (1583-1655) was a Jesuit scholar from Siena who began his career as a professor of Hebrew and Syriac. However his focus seems to have shifted to botany and he became head gardener and horticultural consultant to the Barberini family in the 1620s (David Freedberg, The Eye of the Lynx, p. 38). In 1633, Ferrari published De Florum Cultura, which was notable for both its taxonomical ambitions and its focus on cultivating flowers for ornament rather than medicinal use, and included suggestions for garden plans and flower arrangements (Freedberg, The Eye of the Lynx, p. 38; Freedberg, ‘Cassiano, Ferrari and their Drawings of Citrus Fruit’, p. 49).

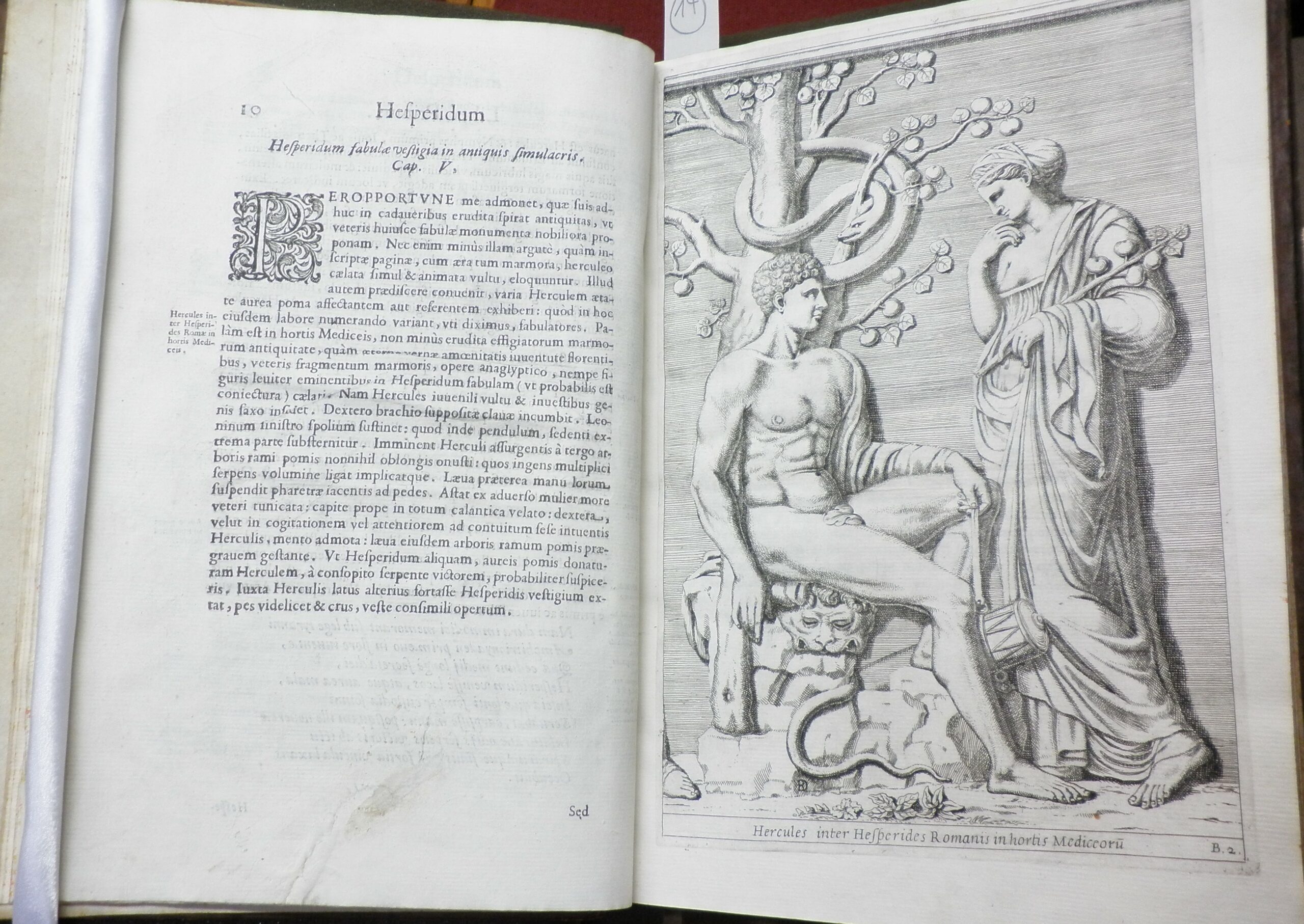

Hercules in the Garden of the Hesperides

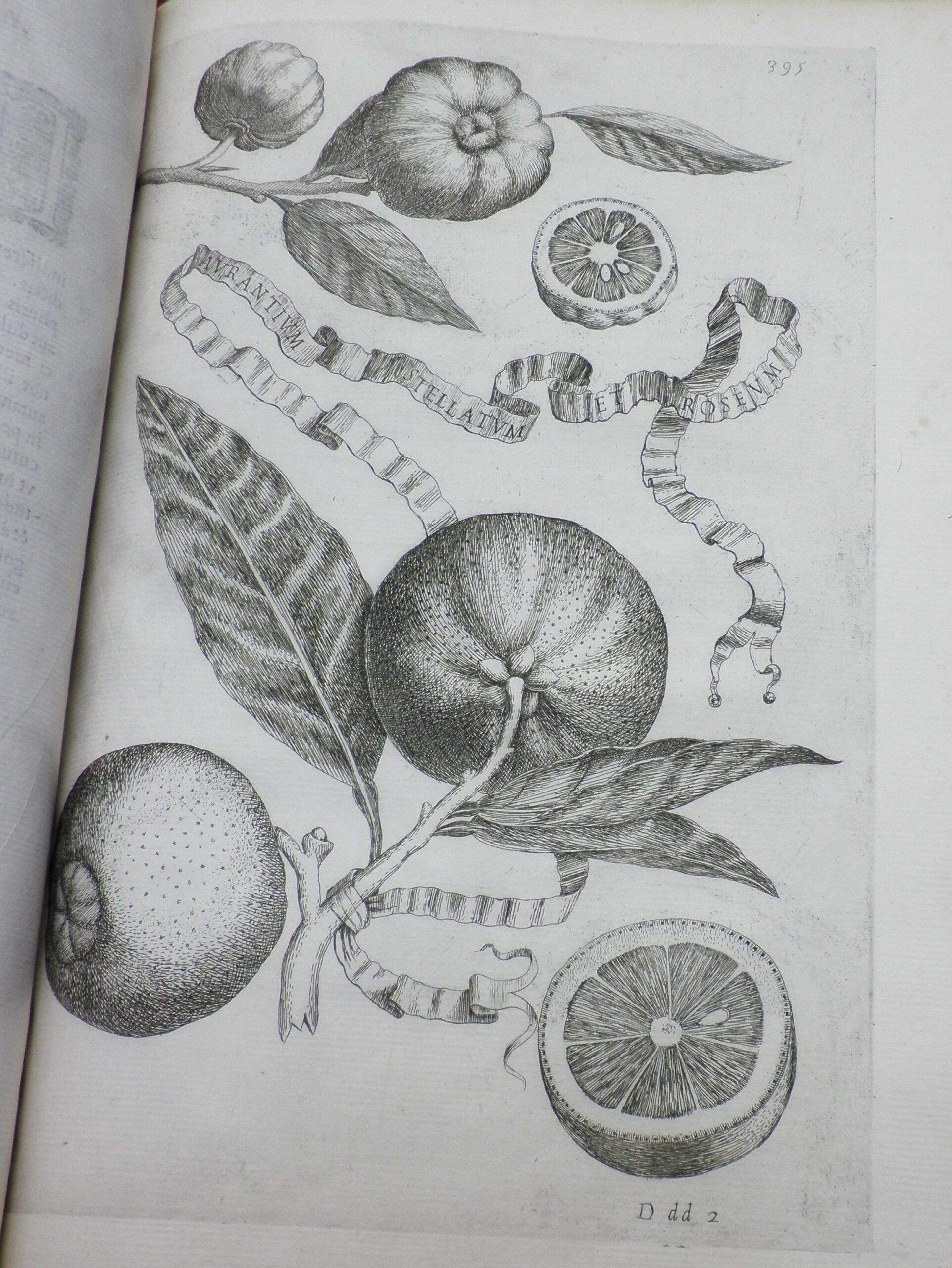

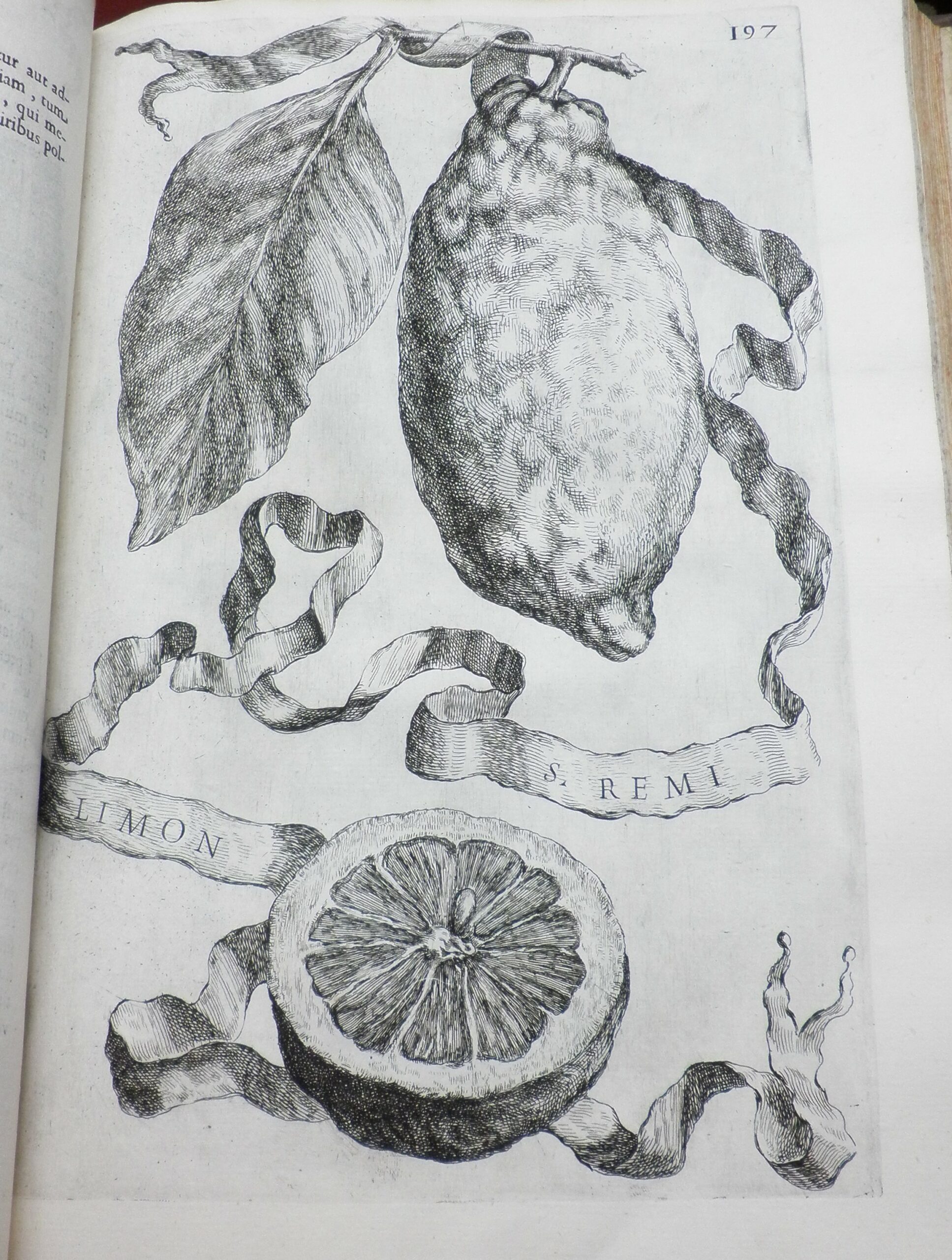

After this, he turned his attention to De malorum aureorum – ‘golden apples’, or citrus fruit. The title alludes to the eleventh labour of Hercules, which demanded he steal ‘golden apples’ from the Garden of the Hesperides. From very early on, the golden apples were depicted in art as citrus fruit (Helena Attlee, The Land Where Lemons Grow, p. 11). In the 1630s, together with his friend and benefactor, Cassiano dal Pozzo, Ferrari sent questionnaires to citrus growers throughout Italy asking for details of citrus fruit in their area – names, descriptions, cultivation, propagation, and uses (Attlee, Land Where Lemons Grow, p. 36). Copies of these questionnaires and some of the responses survive in Cassiano’s personal papers (Freedberg, ‘Cassiano, Ferrari and their Drawings of Citrus Fruit’, pp. 51-54). From the mass of information collected, Ferrari then attempted to classify the many varieties of citrus fruit reported, including hybrids and mutations. This was a monumental task. According to both Freedberg and Attlee, citrus is notoriously difficult to classify, even to this day (Freedberg, ‘Ferrari on the Classification of Oranges and Lemons’, p. 291; Attlee, The Land Where Lemons Grow, p. 35). Citrus can cross-pollinate between species and frequently mutates, and growers graft different varieties together to perpetuate desirable mutations (Attlee, The Land Where Lemons Grow, p. 35). There were also etymological issues as every region had its own names for local fruits (Attlee, The Land Where Lemons Grow, p. 37). Ferrari firmly separated all citrus, even hybrids, into three categories: malum citreum – citrons, malum liminium – lemons, and malum aurantium – oranges (Freedberg, ‘Ferrari on the Classification of Oranges and Lemons’, p. 295). Three of the books in Hesperides are dedicated to describing the different fruits in each category.

Ferrari was particularly interested in deformed fruit, which he termed frutte che scherzano, or ‘joking fruit’ (Attlee, The Land Where Lemons Grow, p.38). According to Helena Attlee, this interest was typical of citrus collectors in Renaissance and Baroque Italy. Collections of curiosities were popular among the wealthy and aristocratic and this extended to gardens, where citrus held a prominent place among collections of rare and exotic plants. Deformed fruit, such as digitated lemons, were known as bizzarrie and were prized specimens of these collections (Attlee, The Land Where Lemons Grow, pp. 7-9).

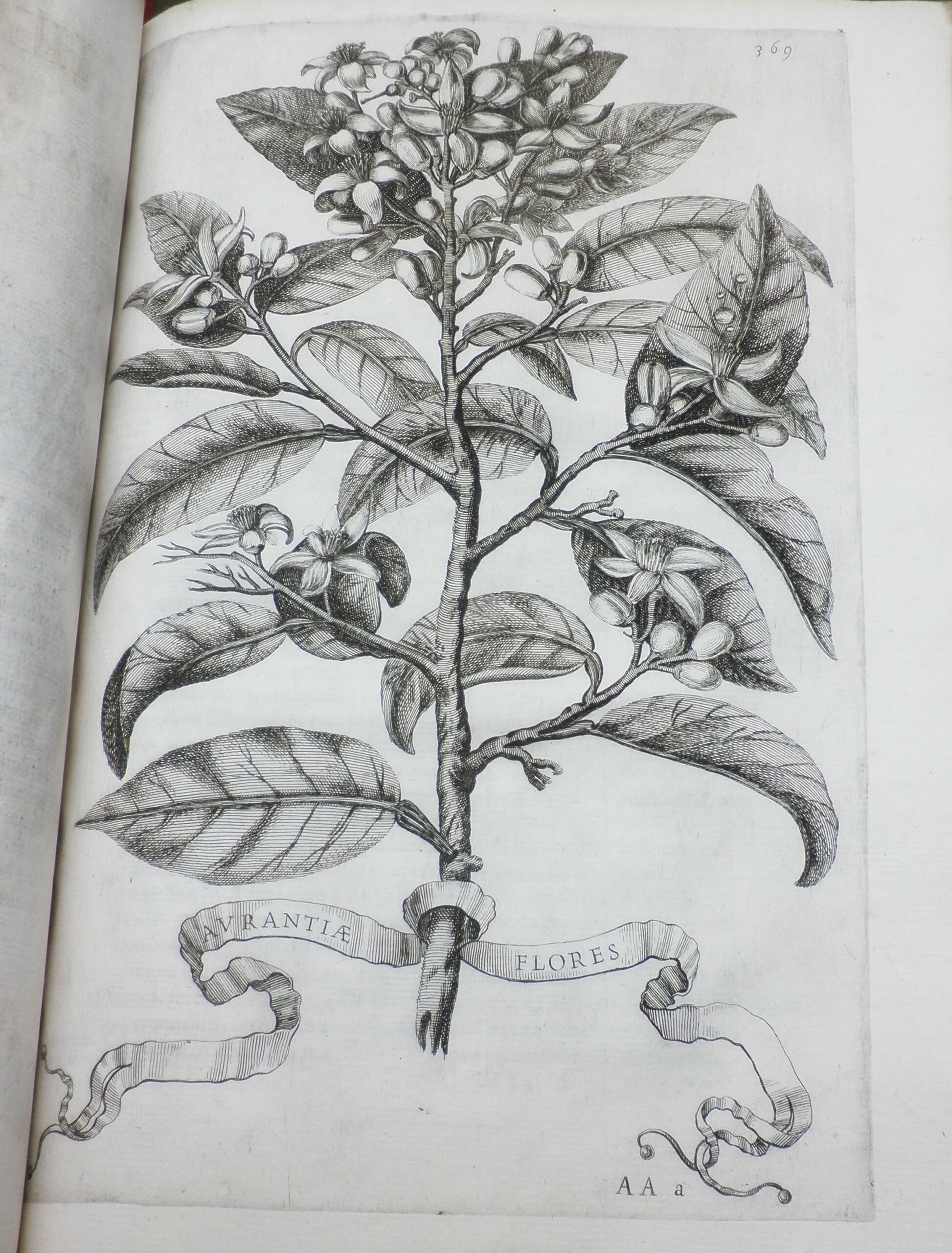

One of the most striking things about Hesperides is the illustrations. But these illustrations were not just for decoration, they were an integral aspect of Ferrari’s classification. Through Cassiano, Ferrari was associated with the Accademia dei Lincei, the first modern science academy in Europe, which was founded in 1603 by Federico Cesi and counted Galileo among its members (Rea Alexandratos, ‘With the true eye of a lynx’, p. 74). The Linceans emphasised the importance of visual observation in understanding the world (Freedberg, The Eye of the Lynx, p. 3). To this end, several Linceans commissioned and collected detailed drawings of the natural world, from fruit and flowers, to animals, fossils, and geological specimens (Freedberg, The Eye of the Lynx, p. 18). Cassiano dal Pozzo’s collection was perhaps the most extensive and famous. It became known as his ‘Paper Museum’ and was widely consulted by European scholars in the seventeenth-century (Alexandratos, ‘With the true eye of a lynx’, p. 93).

Ferrari shared this interest in visual observation as a basis for classification. To classify different fruits, he studied their colour, texture, and seeds, as well as flowers and leaves (Freedberg, ‘Ferrari on the Classification of Oranges and Lemons’, p. 295). In collecting information, Cassiano and Ferrari requested specimens and drawings of fruit whenever possible (Freedberg, ‘Cassiano, Ferrari and their Drawings of Citrus Fruit’, p. 56). In order to fully document the many varieties of citrus Ferrari identified, Hesperides contains numerous detailed botanical engravings, which often show flowers and cross-sections, as well as whole fruits. The engravings were done by Cornelius Bloemaert and were based on paintings of citrus fruit by Vincenzo Leonardi, which had been commissioned by Cassiano for the Paper Museum (Freedberg, The Eye of the Lynx, pp. 53-54).

Botanical illustrations are not the only works of art in Hesperides. Ferrari and Cassiano also commissioned allegorical images from significant artists of the day, including Nicolas Poussin, to illustrate the more literary sections of Hesperides (Freedberg, The Eye of the Lynx, p. 47). The first book of Hesperides focuses on mythology, archaeology and ethnography surrounding citrus (Freedberg, ‘Ferrari on the Classification of Oranges and Lemons’, p. 296). Additionally as Freedberg points out, the division between sciences and arts was less pronounced in the seventeenth-century and although Ferrari attempted a scientific classification of citrus fruit, he did not scruple to provide more poetic explanations where scientific ones could not be found (Freedberg, ‘Ferrari on the Classification of Oranges and Lemons’, p. 299-305; Attlee, The Land Where Lemons Grow, p. 38). Several of the allegorical plates depict the arrival of citrus fruits in Italy and the others illustrate Ferrari’s own literary explanations of deformed and unusual fruit, most of which seem to be about tragic characters transforming into citrus trees (Freedberg, ‘Ferrari on the Classification of Oranges and Lemons’, p. 299; Freedberg, ‘From Hebrew and gardens to oranges and lemons’, p. 52).

Our copy of Hesperides belonged to our great patron George Clarke, as indicated by his bookplate and ownership marking.

Though Clarke was particularly interested in architecture, his collection spans a broad range of subjects, as was typical of an eighteenth-century gentleman’s library. So it is not surprising that he would have owned a work such as Hesperides, which David Freedberg describes as ‘one of the most important attempts at the classification of any single genus of fruit before Linnaeus’ (Freedberg, ‘Ferrari on the Classification of Oranges and Lemons’, p. 291).

Renée Prud’Homme, Assistant Librarian

Bibliography

- Alexandratos, Rea, ‘“With the true eye of a lynx”: The Paper Museum of Cassiano dal Pozzo’ in David Attenborough, Susan Owens, Martin Clayton, and Rea Alexandratos, Amazing Rare Things: The Art of Natural History in the Age of Discovery (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2009)

- Attlee, Helena, The Land Where Lemons Grow (London: Penguin, 2014)

- Freedberg, David, ‘Cassiano, Ferrari and their Drawings of Citrus Fruit’ in David Freedberg and Enrico Baldini, Citrus Fruit (London: Harvey Miller, 1997)

- Freedberg, David, The Eye of the Lynx: Galileo, his Friends, and the Beginnings of Modern Natural History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002)

- Freedberg, David, ‘Ferrari on the Classification of Oranges and Lemons’, in Elizabeth Cropper, Giovanna Perini, and Francesco Solinas (eds.), Documentary Culture: Florence and Rome from Grand-Duke Ferdinand I to Pope Alexander VII: Papers from a Colloquium Held at the Villa Spelman, Florence 1990 (Bologna: Nuova Alfa Editorale, 1992)

- Freedberg, David, ‘From Hebrew and gardens to oranges and lemons: Giovanni Battista Ferrari and Cassiano dal Pozzo’, in Francesco Solinas (ed.), Cassiano dal Pozzo: Atti del Seminario Internazionale di Studi (Rome: De Luca, 1989)