On the scaffold with a king

30th January 2016

On the scaffold with a king

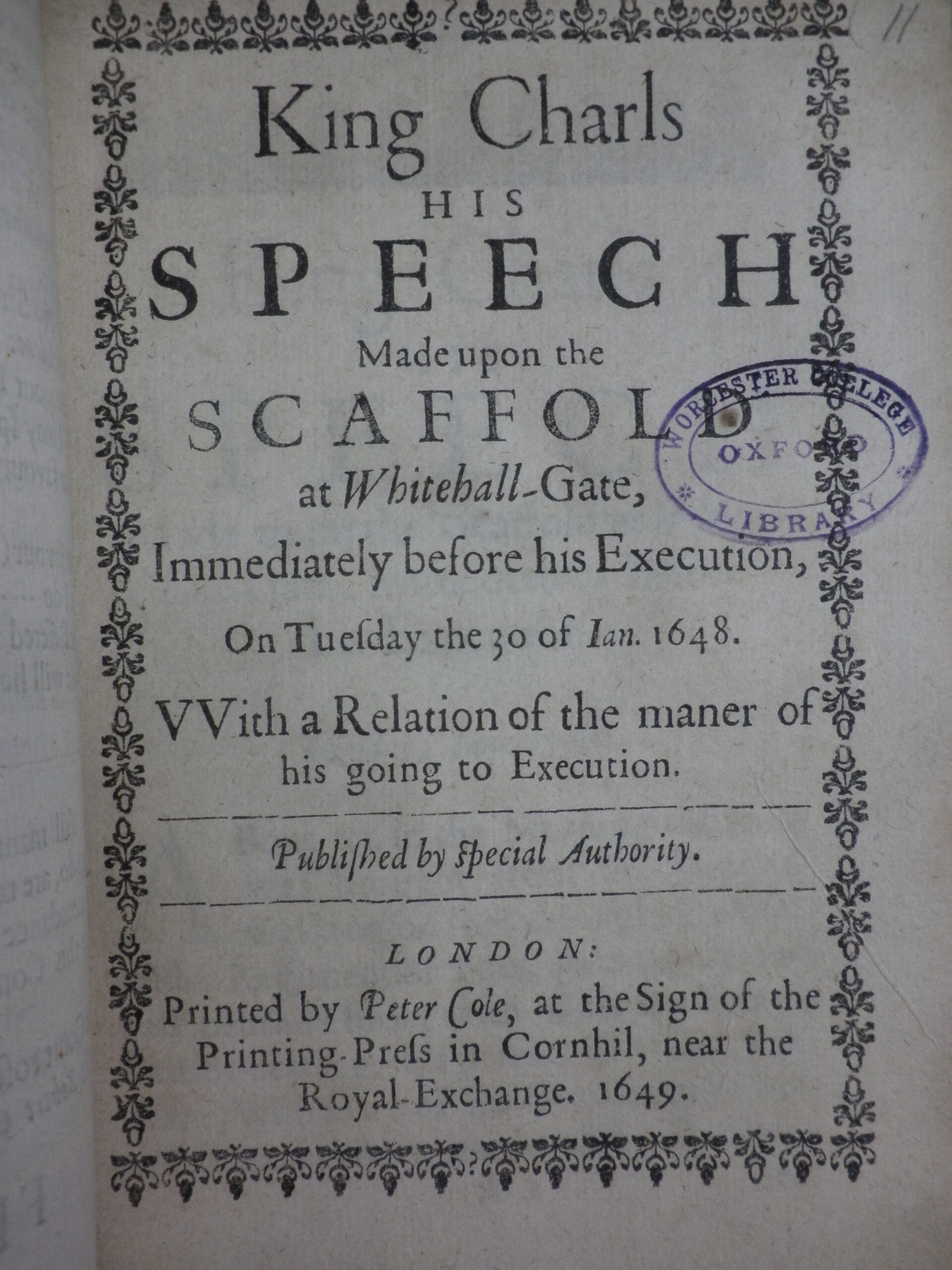

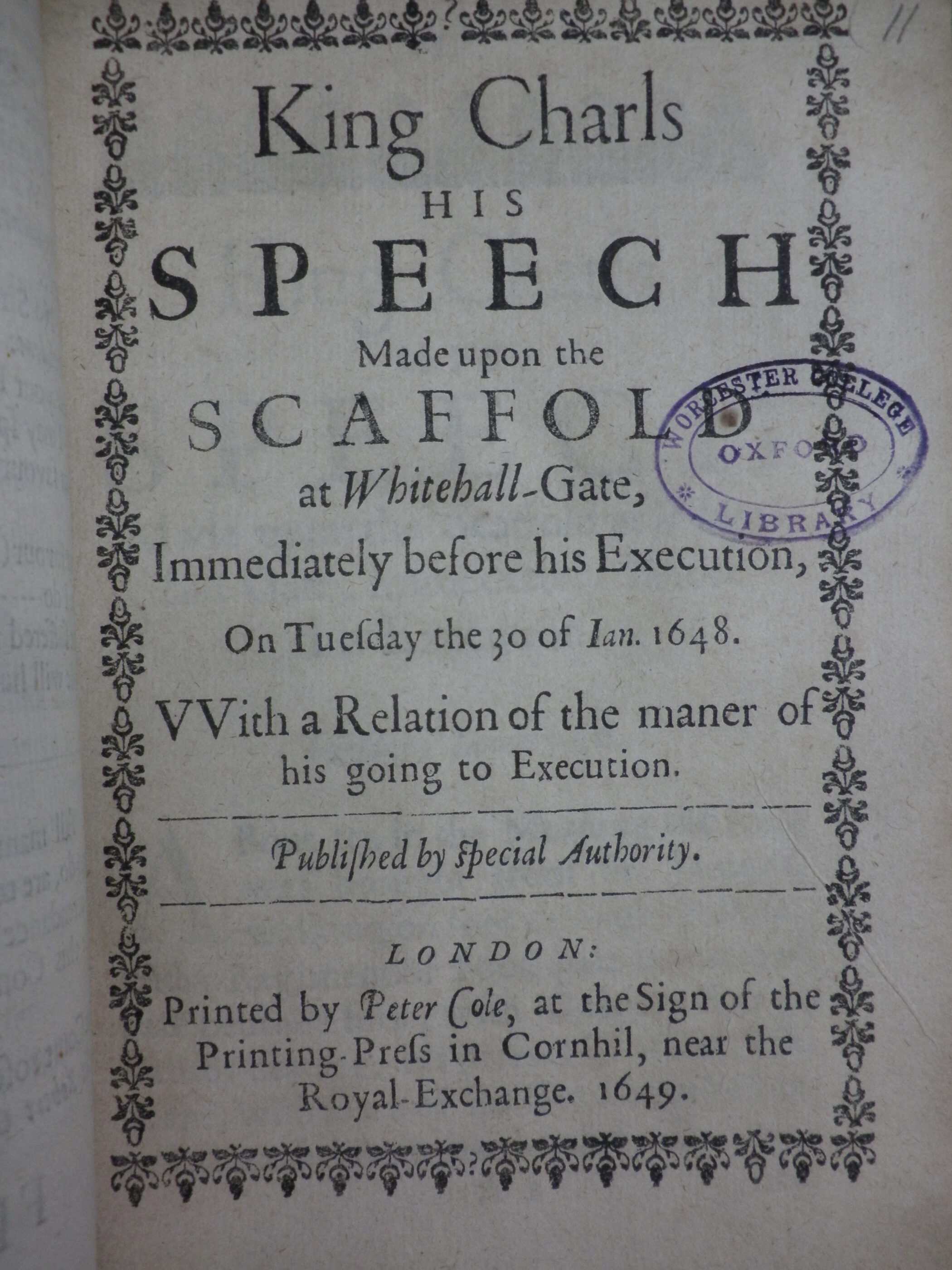

King Charls his speech made upon the scaffold at Whitehall-Gate, immediately before his execution, on Tuesday the 30 of Ian. 1648. VVith a relation of the maner of his going to execution. Published by special authority.

London : printed by Peter Cole, at the Sign of the Printing-Press in Cornhil, near the Royal-Exchange, 1649.

14, [2] pages ; quarto.

As the first in a series of monthly posts on ‘Treasures’ from the Library and Archive collections of Worcester College, Oxford, we have chosen an item from the William Clarke pamphlet collection, a collection of around 7,000 pamphlets and newsbooks from the Civil War period, second in size only to the Thomason Tracts (the huge collection of Civil War pamphlets assembled by the bookseller George Thomason, now in the British Library) and containing much unique material. Whilst this pamphlet will be familiar to readers of Jonathan Bate and Jessica Goodman’s Worcester: portrait of an Oxford College, it is a fine item to begin this series. Not only does it provide a link to George Clarke (1661-1736; see http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/5496?docPos=2), son of William Clarke (1624-1666; see http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/5536?docPos=5) and the Library’s first major benefactor, it covers a subject area, the English Civil War and Interregnum, in which the Library’s special collections are particularly strong, and, in the circumstances of the identification of its important manuscript additions, captures the type of discovery waiting to be made in special collections libraries like that at Worcester College, Oxford.

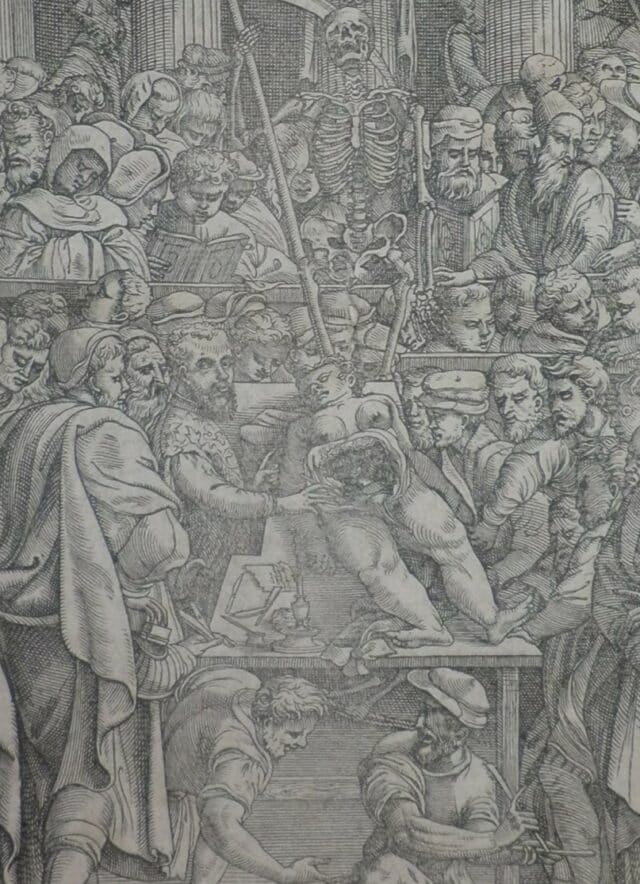

The pamphlet King Charls his speech made upon the scaffold… is by no means a rare title: the English Short Title Catalogue lists nine editions. Its publisher, Peter Cole (d. 1665; see http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/75231), rushed to register it with the Stationers’ Company on 31st January 1648 [i.e. 1649], the day immediately after the execution, in order to take advantage of a market eager for accounts of the king’s final hours (see Barnard, ‘London publishing, 1640-1660: crisis, continuity, and innovation’, page 5). For whilst many had attended the execution outside the Banqueting House in Whitehall, the king’s distance from the crowd and the icy wind meant that few could have heard his words, a point Charles himself makes in the published speech: ‘I shall be very little heard of anybody here…’. Yet heard Charles can be through the printed words of the pamphlet, in a speech in which he sought ‘to clear myself both as an honest man, and a good King, and a good Christian’ – finally replying to the charges that had been brought against him at his trial in the Great Hall at Westminster (here illustrated in a 1728 print by Claude Dubosc after Peter Angelis, also from the Library collections).

Dubosc after Angelis, The Tryal of the King, London, 1728

The pamphlet records Charles’ words with only a brief introduction and little comment apart from ten marginal notes clarifying for the most part the king’s movements. Charles used his speech to claim martyr status (‘I am the Martyr of the People’) and the text printed by Cole was later included in King Charles his Tryall, a work that was banned by the Commonwealth: on 19 November 1649 a warrant was issued for Cole’s arrest along with that of two other London stationers for printing this account of the trial. This is somewhat remarkable given that Peter Cole was no Royalist who sought to canonise the dead king, but rather ‘a radical with possible Leveller connections’ (Barnard, page 5), who had published many of the petitions circulated by Puritan leaders (see ODNB). As John Barnard has noted: ‘For Cole… profit was more important than… political beliefs’ (Barnard, pages 5-6).

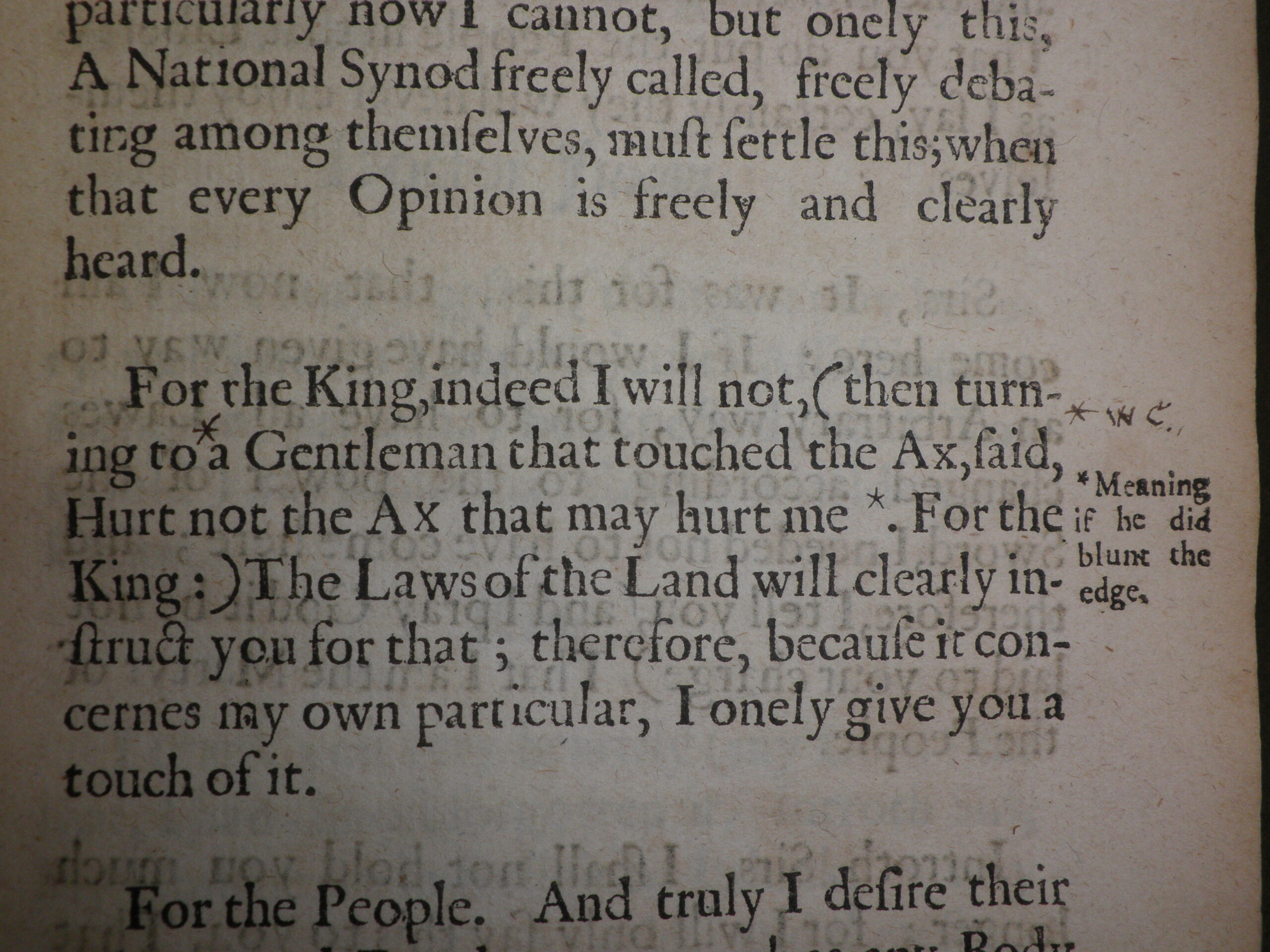

C.V. Wedgewood, author of The trial of Charles I, calls this pamphlet ‘the best of the contemporary pamphlets’ (Wedgewood, page 241) on the death of the king, but that is not why we have selected it as a treasure. Indeed, Worcester has a second copy of the pamphlet, but that reproduced here carries exciting manuscript additions. As Lesley Le Claire (Librarian 1977-1992) pointed out, this pamphlet is ‘indicative of [William] Clarke’s rare knack for finding himself at the centre of things’ (in Mendle (ed.), The Putney Debates of 1647, page 30): on page 9 of his copy of the pamphlet in the right-hand margin, William Clarke has inked in his own initials linked by an asterisk to the phrase ‘a Gentleman that touched the Ax’:

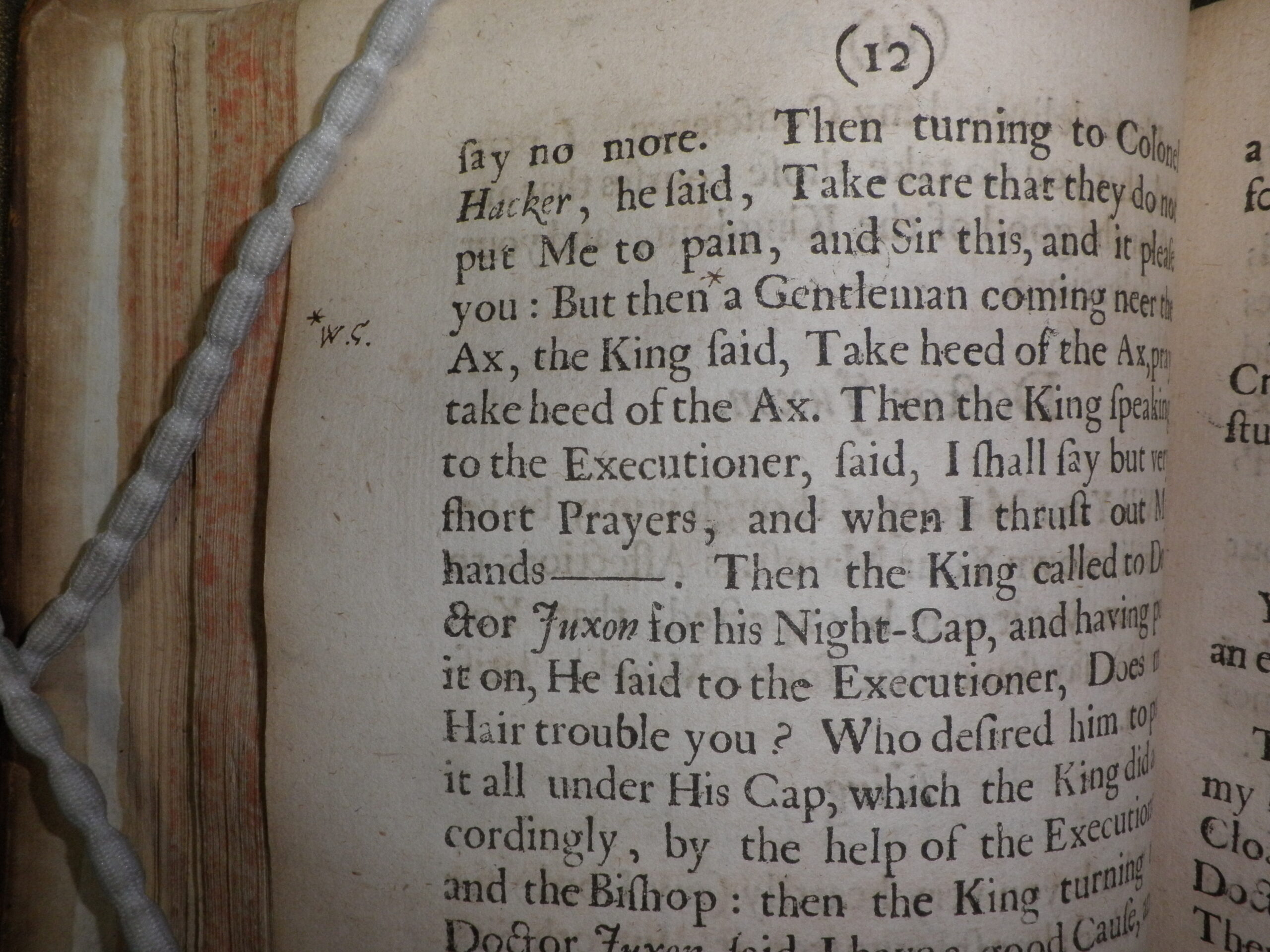

The action is repeated on page 12, where Clarke’s cloak again must have accidentally brushed the axe:

In 1649 William Clarke was one of three army secretaries ordered onto the scaffold by the New Model Army grandees (Thomas Fairfax and Oliver Cromwell among them) who had orchestrated both the trial and execution, in order to obtain the most accurate possible account of the bearing, and words, of the king. This was a routine procedure on high-profile occasions (see Henderson in Mendle (ed.), The Putney Debates of 1647, page 43) and Clarke’s presence there is known from England’s Black Tribunall published in 1703 by Henry Playford, descendant of William Clarke’s close friend John Playford; the initials in the Worcester copy of this pamphlet provide further confirmation. Even now it is easy to imagine the excitement that Lesley and the Canadian scholar Professor Ian Gentles (whose account of Clarke’s role at Charles’ execution can be found in his The New Model Army in England, Ireland and Scotland, 1645-1653, pages 311 ff.) must have felt as they realized the import of the initials: for a reader can almost reach back through the pages of this pamphlet from its shelves in Worcester College Library to the very scaffold on which a king was executed.

Mark Bainbridge, Librarian

With thanks to Dr Frances Henderson

Bibliography

- Barnard, J., ‘London publishing, 1640-1660: crisis, continuity, and innovation’, in Book History 4 (2001), pages 1-16

- Bate, J. and Goodman, J., Worcester: portrait of an Oxford College (London: Third Millennium, 2014)

- Gentles, I., The New Model Army in England, Ireland and Scotland, 1645-1653 (Oxford: Blackwell, 1992)

- Henderson, F., ‘Reading, and writing, the text of the Putney debates’, in M. Mendle (ed.), The Putney Debates of 1647: the army, the Levellers and the English state (Cambridge: CUP, 2001), pages 36-50

- Le Claire, L., ‘The survival of the manuscript’, in M. Mendle (ed.), The Putney Debates of 1647: the army, the Levellers and the English state (Cambridge: CUP, 2001), pages 19-35

- Wedgewood, C. V., The trial of Charles I (reprint edition; London: The Reprint Society, 1966)