Murder most foul?

29th May 2017

Murder most foul?

The Ardlamont Mystery Solved. By Alfred J. Monson. To which is appended Scott’s Diary.

London: Marlo & Co. [1894]

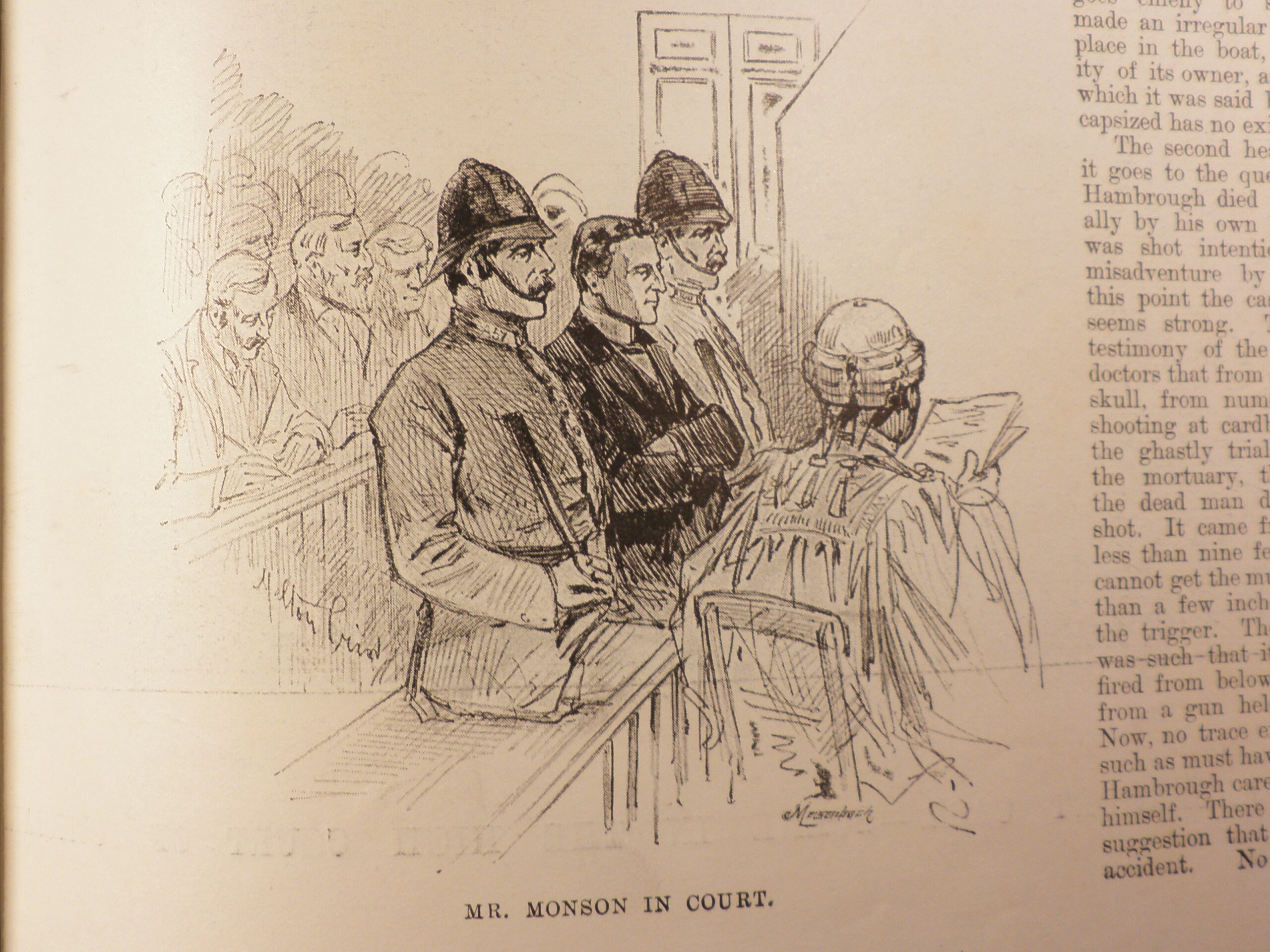

This rather curious pamphlet recently came to our attention through an enquiry from a researcher. In December 1893, Alfred Monson was tried for both the murder and attempted murder of Cecil Hambrough. He was released after the jury returned the peculiarly Scottish verdict of ‘Not Proven’. This pamphlet, written by Monson the year after, tells his side of the story.

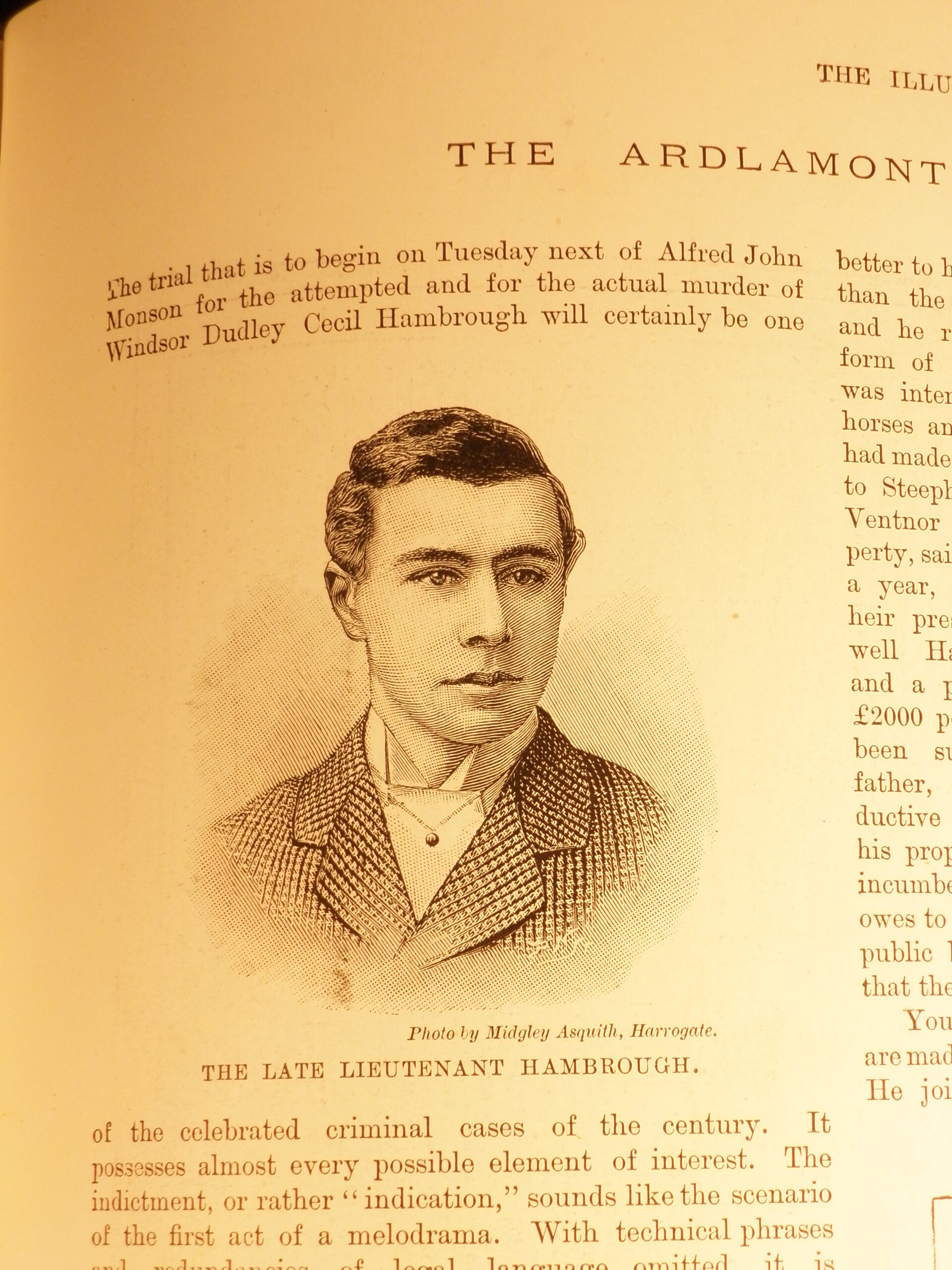

Cecil Hambrough, The Illustrated London News, December 9, 1893

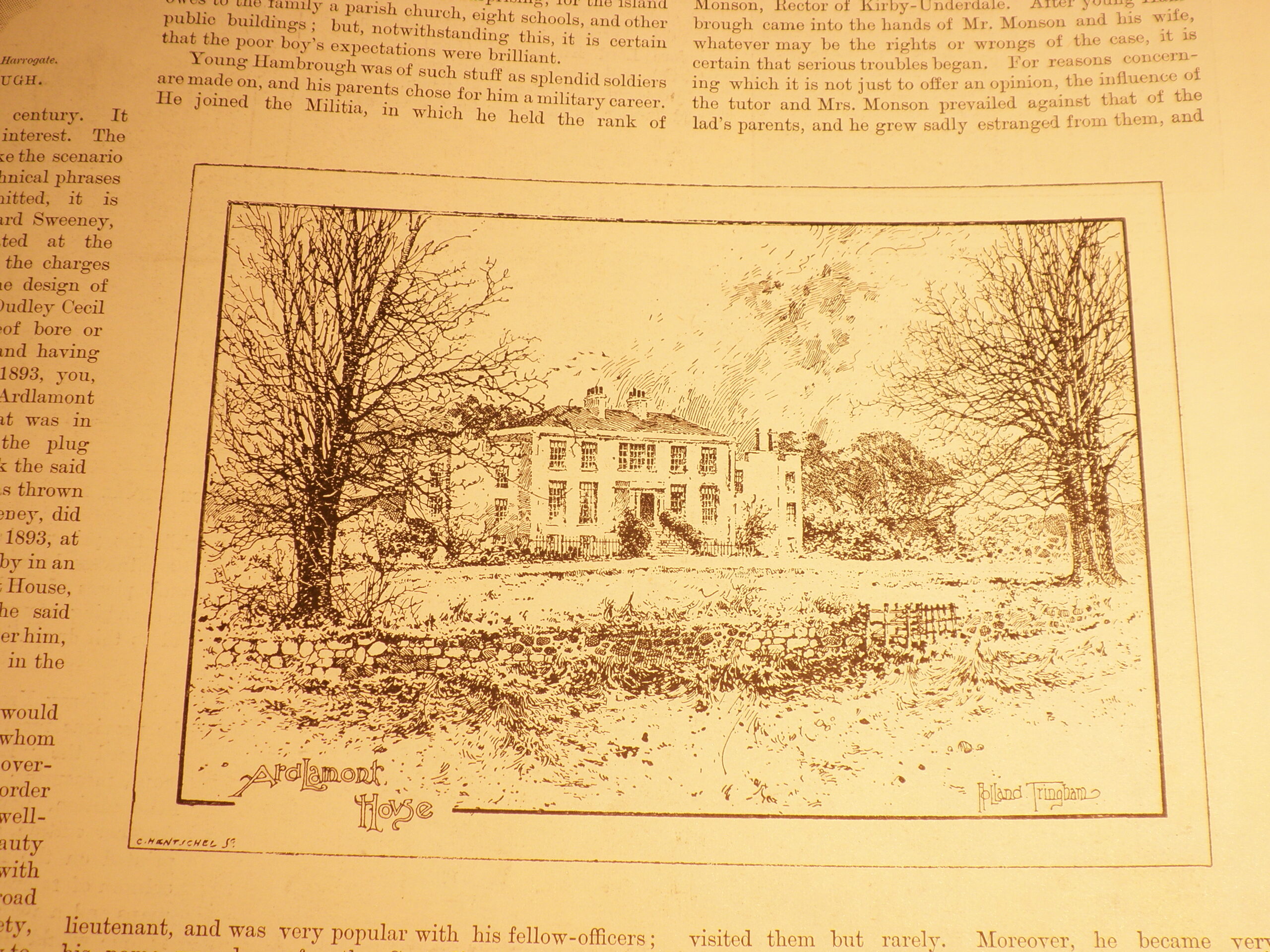

The most basic facts of the case are these: in August 1893, Cecil Hambrough, aged 20 and expecting to come into a reasonably large fortune on his majority, along with his tutor, Alfred Monson, arranged to rent the Ardlamont estate in Argyll for the shooting season. A man called ‘Scott’, who was purported to be a boating engineer, joined them in Ardlamont. On the night of the 9th of August, Monson and Hambrough went out splash-net fishing and the boat sank, leaving Hambrough (who could not swim) stranded on a rock. Monson swam to shore to fetch another boat and rowed them both back. On the 10th of August, while out shooting with Monson and Scott, Cecil Hambrough was shot dead.

Ardlamont House, The Illustrated London News, December 9, 1893

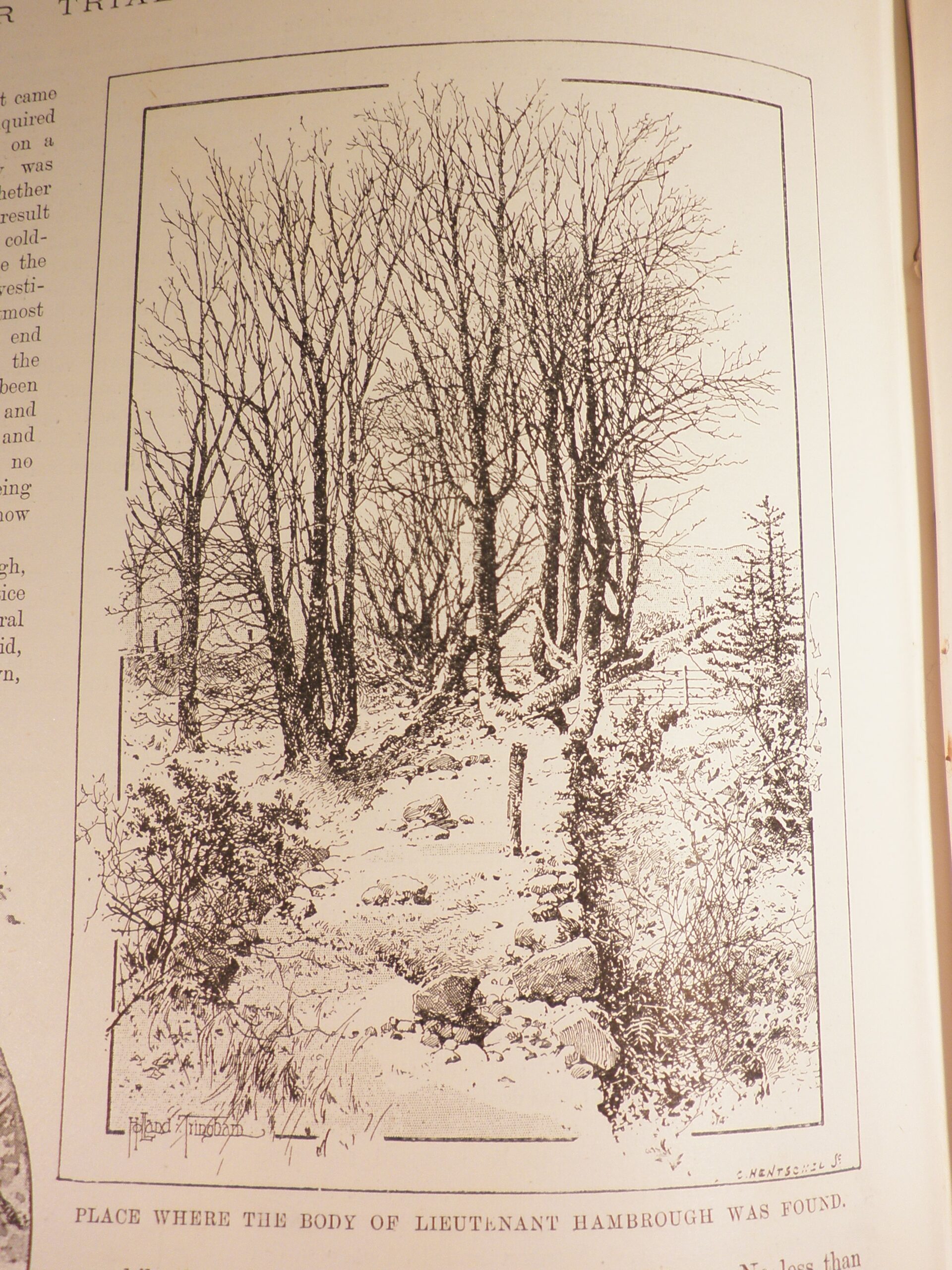

Monson and Scott alleged that Cecil had accidently shot himself while climbing over a wall. Monson stated he was some distance away in another part of the wood when he heard the shot, and Scott was not carrying a gun. Cecil’s body was removed to the house where it was examined by a local doctor, Dr Macmillan, who found the story believable and certified the death as accidental. The case appeared closed.

A couple of weeks later however, it came to the attention of the Procurator Fiscal that just days before his death, Cecil had insured his life for £20,000 and assigned the policies to Mrs Monson, and the Monsons were now trying to collect. The Procurator Fiscal decided to investigate further and found that not only were there some evidential inconsistencies, but that Monson was at the centre of a complex web of dodgy financial dealings involving the Hambrough family. And the mysterious ‘Scott’, who had shown no evidence of actually being a boating engineer, had disappeared. The Procurator Fiscal and the Crown decided that neither the shooting nor the boating incident the night before were accidents, and charged Monson and Scott with murder and attempted murder.

The scene of the shooting, The Illustrated London News, December 9, 1893

A full account of the case is well beyond the scope of a blogpost – for an excellent, if not exactly succinct, account, see William Roughead, ‘The Ardlamont Mystery; or the Misadventures of Mr Monson’ in Rogues Walk Here or Classic Crimes. True enthusiasts can read a full report of the trial, including witness statements, in Trial of A. J. Monson, edited by John W. More (Edinburgh 1921). Taking place over ten days, with dozens of witnesses called (one of whom was Dr Joseph Bell, the prototype for Sherlock Holmes, who testified for the prosecution), Monson’s trial was a large and complex affair (Roughead, Rogues Walk Here, pp. 32, 40). The primary points of dispute were over means and motive. Experts for the prosecution and defence clashed over ballistic and medical evidence as to the distance and angle necessary to explain the gunshot wound and whether the body had truly fallen where Monson claimed. There were also disputes over who had been carrying which gun; according to More, Monson changed his story as to which guns he and Cecil were carrying. Also, rather strangely, Monson and Scott had taken both guns back to the house and emptied the cartridges before even alerting the household of the accident (More, Trial of A.J. Monson, p. 6 and Roughead, Rogues Walk Here, p. 40).

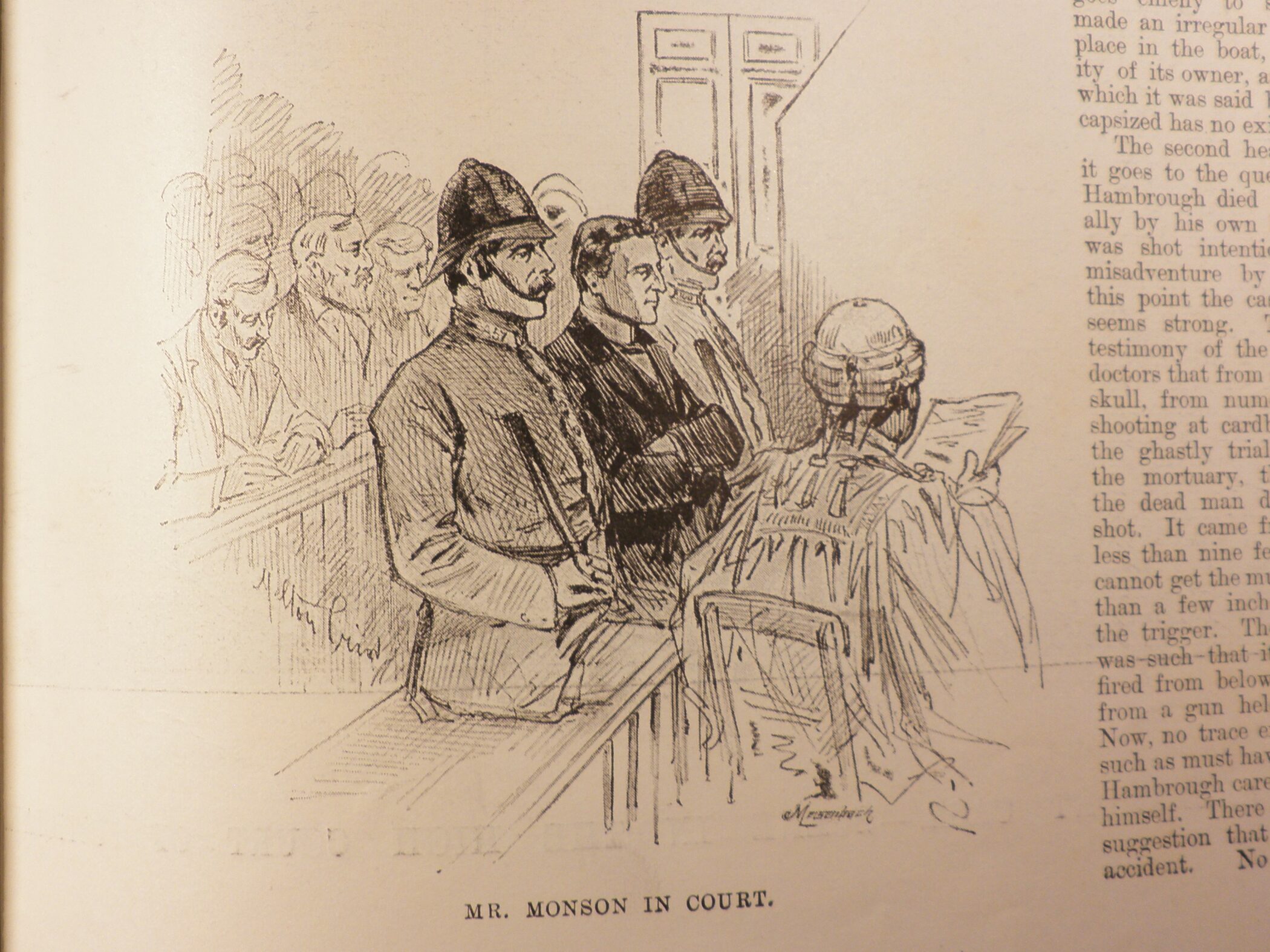

Monson in court, The Illustrated London News, December 23,1893

Proving the motive for the crime was even more complicated. Although Cecil had insured his life for the benefit of the Monsons by assigning the policies to Mrs Monson, the assignment was invalid because he was underage, and the Monsons were not able to collect the money. The prosecution argued that Monson was not aware that Cecil’s age would make the assignment invalid and killed Cecil for the insurance money, as evidenced by the attempts to cash in after he died. The defence insisted that he was aware of this and that the insurance assignments were intended as an acknowledgement of Cecil’s indebtedness to the Monsons, whom he intended to repay on reaching his majority. Cecil, they argued, was more valuable to Monson alive than dead (More, Trial of A.J. Monson, p. 7). The defence wrote off the attempts to cash in the policies as just ‘bluffing’ – a cheeky try for the cash (Roughead, Rogues Walk Here, pp. 44-45). It turned out that Monson had had a long and uncomfortable financial relationship with the Hambroughs – Cecil’s father Major Hambrough was also in substantial debt, and had been introduced to Monson through a mutual acquaintance while trying to find creative ways to regain control of his finances. Over the course of the trial it also became clear that this was not Monson’s first involvement in shady financial dealings and that he had actually been declared bankrupt in 1892 (More, Trial of A.J. Monson, p. 2; for more, see Roughead, Rogues Walk Here). It also became evident that he had forged a signature to obtain the lease of Ardlamont and that the insurance policies in question had been obtained fraudulently (Roughead, Rogues Walk Here, p. 11; Lewis and Bombaugh, Stratagems and conspiracies to defraud life insurance companies, pp. 611-613).

Prosecutor and witness, The Illustrated London News, December 23, 1893

Witnesses at the trial, The Illustrated London News, December 23, 1893

Monson’s trial was a media sensation. Before it had even begun, The Illustrated London News was already stating that it ‘will certainly be one of the celebrated criminal trials of the century’ (December 9, 1893). The large-scale and unsuccessful manhunt for ‘Scott’, who was now believed to be Edward Sweeney, also known as Ted Davis the bookmaker, had also captured the public’s imagination and lent an air of mystery to the case. Over 100 pressmen attended the trial and The Scotsman devoted an average of 20 columns to it every day (Roughead, Rogues Walk Here, p.4).

Trial scene, The Illustrated London News, December 23, 1893

After deliberating for just 73 minutes, the jury returned a verdict of ‘Not proven’, an alternative to ‘Guilty’ and ‘Not guilty’ which exists in Scotland. In practice, the verdict is an acquittal, but it is an acquittal with doubt. In Blackwood’s Magazine in 1906, Lord Moncrieff wrote of this option:

‘When, therefore, the verdict “Not Guilty” being available, a jury contents itself with finding the modified verdict “Not Proven,” the verdict reflects, and is intended to reflect, unfavourably upon the character of the person acquitted.’(‘The Verdict “Not Proven”’, Blackwood’s Magazine, June 1906)

Perhaps to dispel these unfavourable reflections, or to try to make a little something out of his misadventure, Monson published his side of the story in this pamphlet in 1894. Our copy likely made its way to our collection through the eclectic collecting tendencies of Henry Allison Pottinger (Librarian of Worcester College 1884-1911), who left the library a large and varied collection of nineteenth-century pamphlets. Over the course of 72 pages, Monson explains his version of both the boating accident and the shooting, as well as going into detail about his financial dealings with the Hambrough family. He is particularly critical of the Scottish justice system and the Procurator Fiscal involved in the case. He repeatedly asserts that ‘if the accident to the late Cecil Hambrough had taken place in England, I should never have been accused of murdering him’; a claim based on the practice of holding a public inquest in England (The Ardlamont Mystery Solved, p. 4). He also accuses the Crown Prosecution of concealing evidence which would have helped him, and the Procurator Fiscal of fabricating a murder charge in order to cover his own mistake in failing to take Scott’s evidence on the accidental death before he disappeared, a mistake which Monson insists would have cost the Procurator Fiscal his position.

As The Scotsman commented in its brief description of the work, Monson’s account is ‘remarkable chiefly for things that are left out’ (The Scotsman, January 25, 1894). Monson never truly explains the presence or identity of Scott. Neither does he mention in his rambling description of his financial dealings that he was in fact bankrupt, in substantial debt, and dependent on the handouts of friends for financing. The credibility of the work is undermined further by the inclusion of the bizarre appendix of ‘Scott’s Diary’, an account of Scott’s time while on the run from the police, which bears all the signs of being complete fabrication. The indignation of having these ramblings ascribed to him may have been what finally drove Scott out of hiding. In April 1894, The Pall Mall Gazette published Scott’s, alias Ted Davis’, alias Edward Sweeney’s account of the tragedy. His story largely tallies with Monson’s, though he verifies his identity as Davis/Sweeney and claims that it was Monson who suggested that he adopt an alias while at Ardlamont, so that Monson’s wife wouldn’t know that he had invited a bookie to stay. Regarding Monson’s pamphlet, he states:

‘Now, I have not once during my story tried in any way to blame Mr. Monson for what has happened, believing and knowing him to be quite blameless, so far as an intention to cause me trouble is concerned; but I cannot understand, after all I have suffered through adopting, at his instigation, the name he suggested, why he should have done me the injustice of allowing this absurd and fictitious diary to be published in my name. And here let me at once say the diary is not mine. I never saw it, wrote it, or had any hand in it. It was not written by my consent or knowledge, and does not contain one word of truth.’ (The Pall Mall Gazette, April 11, 1894)

In May 1894, Sweeney presented himself to the courts asking for the sentence of outlawry against him to be lifted, which it was, leaving him a free man (Roughead p. 52). Monson’s pamphlet was not particularly well received by the press, being termed as a ‘catch-penny pamphlet’ by one paper and ‘rubbish’ by another (Roughead, Rogues Walk Here, pp. 50-51).

So, did Alfred Monson kill Cecil Hambrough? Opinion has certainly remained divided since the beginning. Later commentators have tended to believe that Monson was probably guilty (see for example http://www.scotsman.com/lifestyle/the-ardlamont-mystery-tragic-mistake-or-calculated-evil-1-466095), but writing immediately after the verdict, both The Spectator and The Scotsman found the verdict of ‘Not Proven’ to be fair. The Saturday Review, on the other hand, felt it to be somewhat unjust that the option existed, though they did comment that:

‘In the Monson case it can easily be understood that where the prisoner’s life and conduct had been so disreputable, and where, if he was innocent, so many odd and suspicious things had happened, the jury were by no means particularly anxious to pay him the compliment… of a verdict of “Not Guilty”.’ (The Saturday Review, December 30, 1893, p. 729)

Guilty or not, Monson did not appear to have learned his lesson when it came to dodgy financial dealings. In 1898, Monson was again in court as a defendant and this time convicted, with a sentence of five years penal servitude, of insurance fraud.

Renée Prud’Homme, Assistant Librarian

Bibliography

- Lewis, John B and Bombaugh, Charles C., Stratagems and conspiracies to defraud life insurance companies : an authentic record of remarkable cases (2nd ed. Baltimore, 1896), viewed in The Making of Modern Law, Gale (online database)

- Moncrieff (Lord), ‘The Verdict “Not Proven”’, Blackwood’s Magazine, No. MLXXXVIII, Vol. CLXXIX (June 1906), pp. 763-777

- More, John W. (ed.), Trial of A. J. Monson (2nd ed. Edinburgh, [1921?]), viewed in The Making of Modern Law, Gale (online database)

- Roughead, William, Rogues Walk Here, (London, 1934)

Newspapers

- The Illustrated London News (December 9, 1893 and December 23, 1893)

- The Pall Mall Gazette (April, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 1894), viewed in British Library Newspapers, Part I: 1800-1900 (online database)

- The Saturday review of politics, literature, science and art (Dec 30, 1893), viewed in British Periodicals, ProQuest (online database)

- The Scotsman (December 23, 1893 and June 25, 1894), viewed in ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Scotsman (online database)

- The Spectator (December 30, 1893), viewed in Periodicals Archive Online, ProQuest (online database)