Memento Mori: London’s Dreadful Visitation

31st October 2017

Memento Mori: London’s Dreadful Visitation

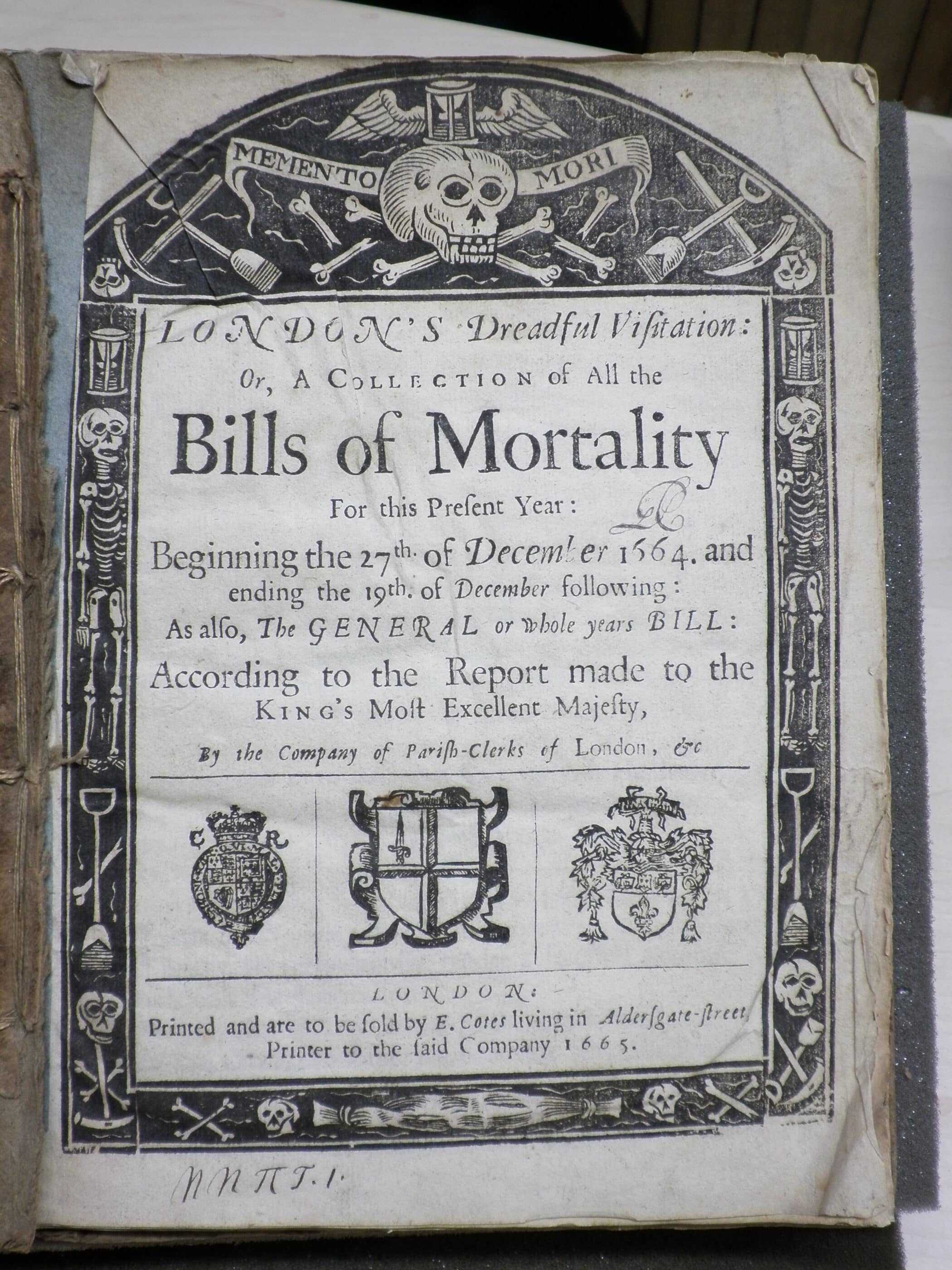

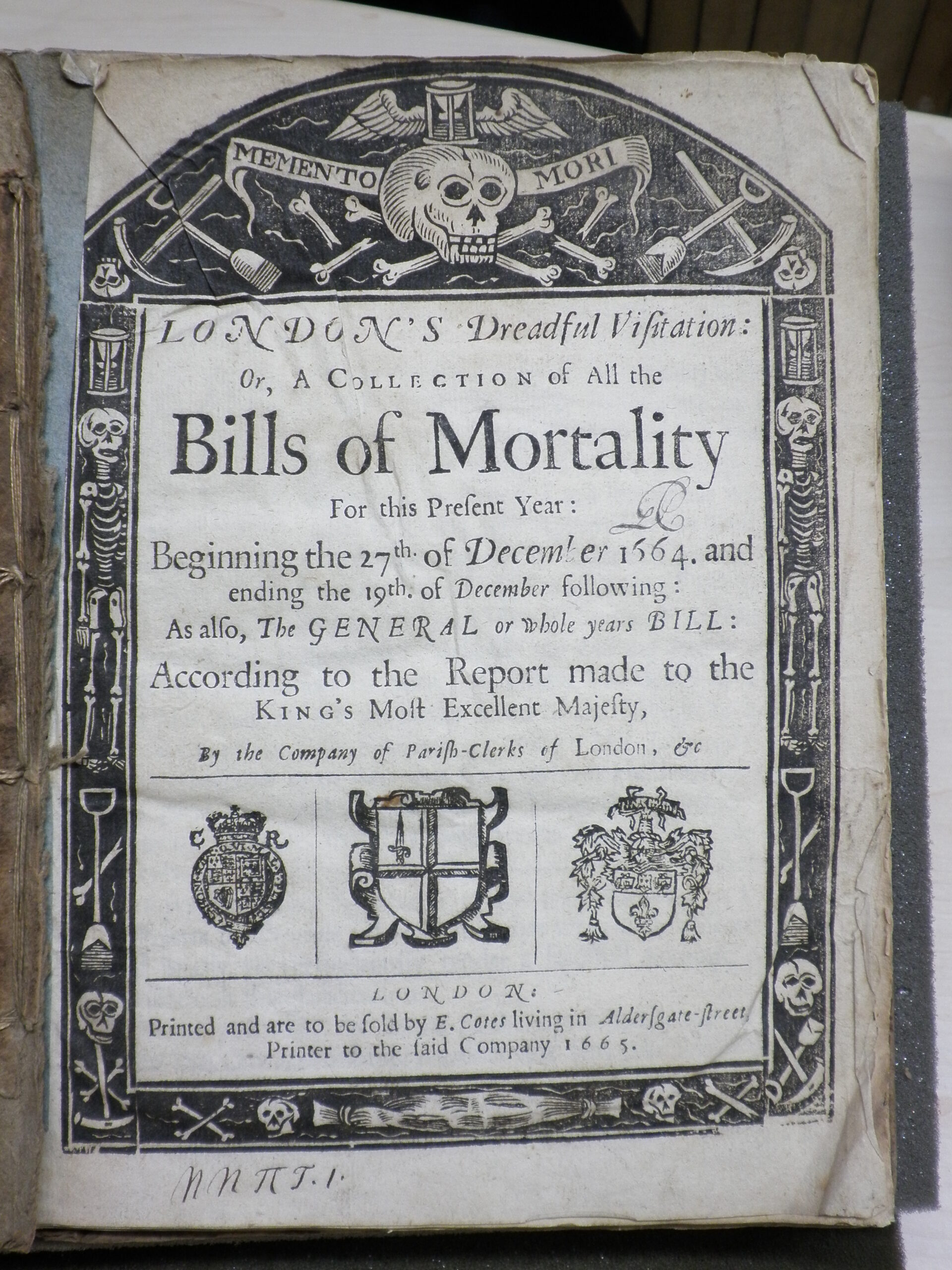

London’s dreadful visitation: or, A collection of all the bills of mortality for this present year: beginning the 27th. of December 1664. and ending the 19th of December following: as also, the general or whole years bill: according to the report made to the King’s most excellent Majesty, by the Company of Parish-Clerks of London, &c.

London : printed and are to be sold by E. Cotes living in Aldersgate-street, printer to the said company, 1665.

[108] pages, folded leaf; quarto.

During the summer the Library hosted participants in a Continuing Education Summer School studying the later seventeenth century. The same group had visited a year earlier, when they were covering the period immediately preceding, the English Civil Wars and the Interregnum, in which the Library’s holdings are particularly strong (see our blog post for January 2016). On this occasion, however, they hoped to see items relating to the two great catastrophes of the early Restoration: the Great Plague of 1665-1666 and the Great Fire of 1666. We have touched upon the Library’s holdings which relate to the Great Fire (see our blog post for September 2016), but what would illustrate the Plague?

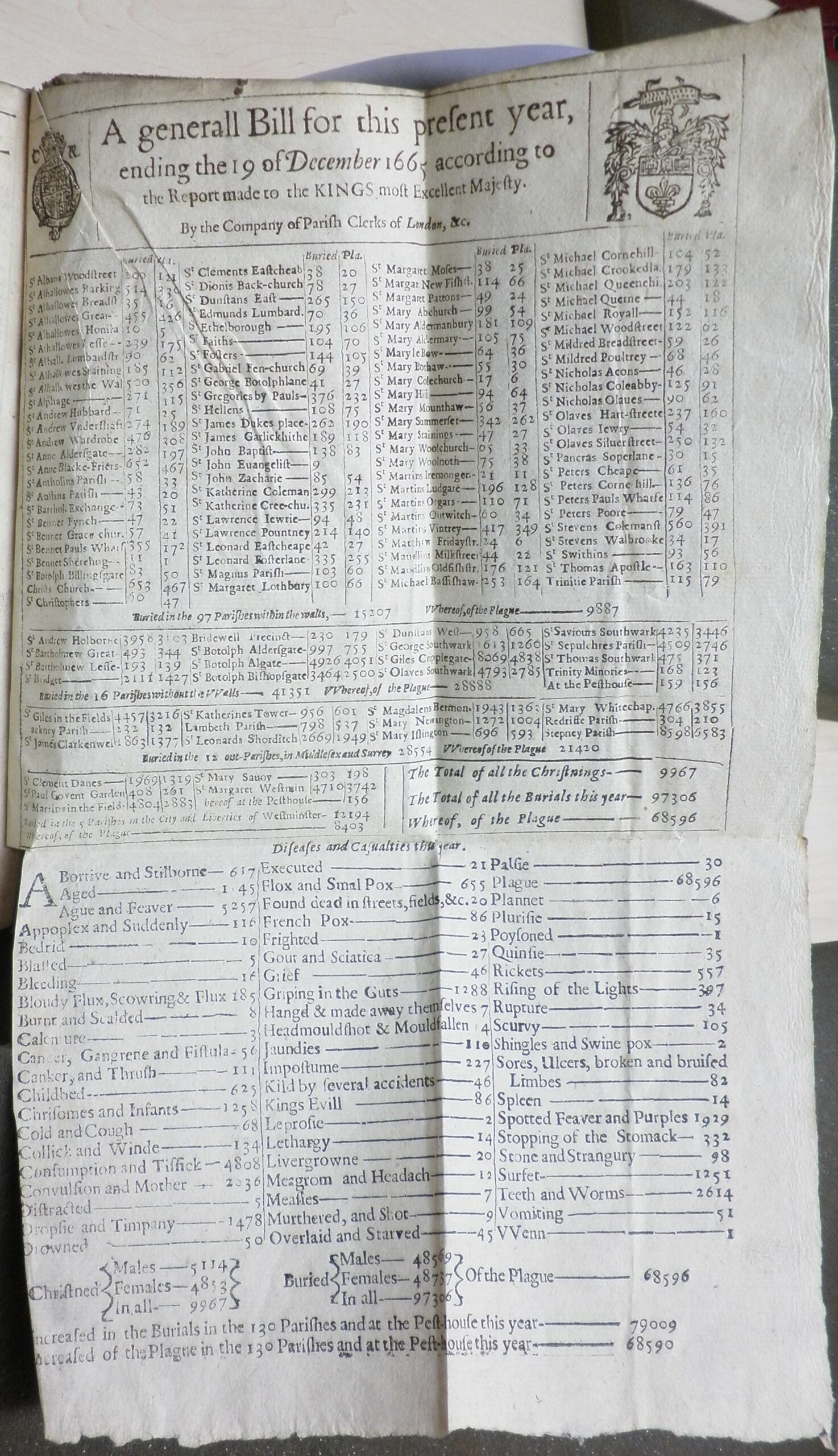

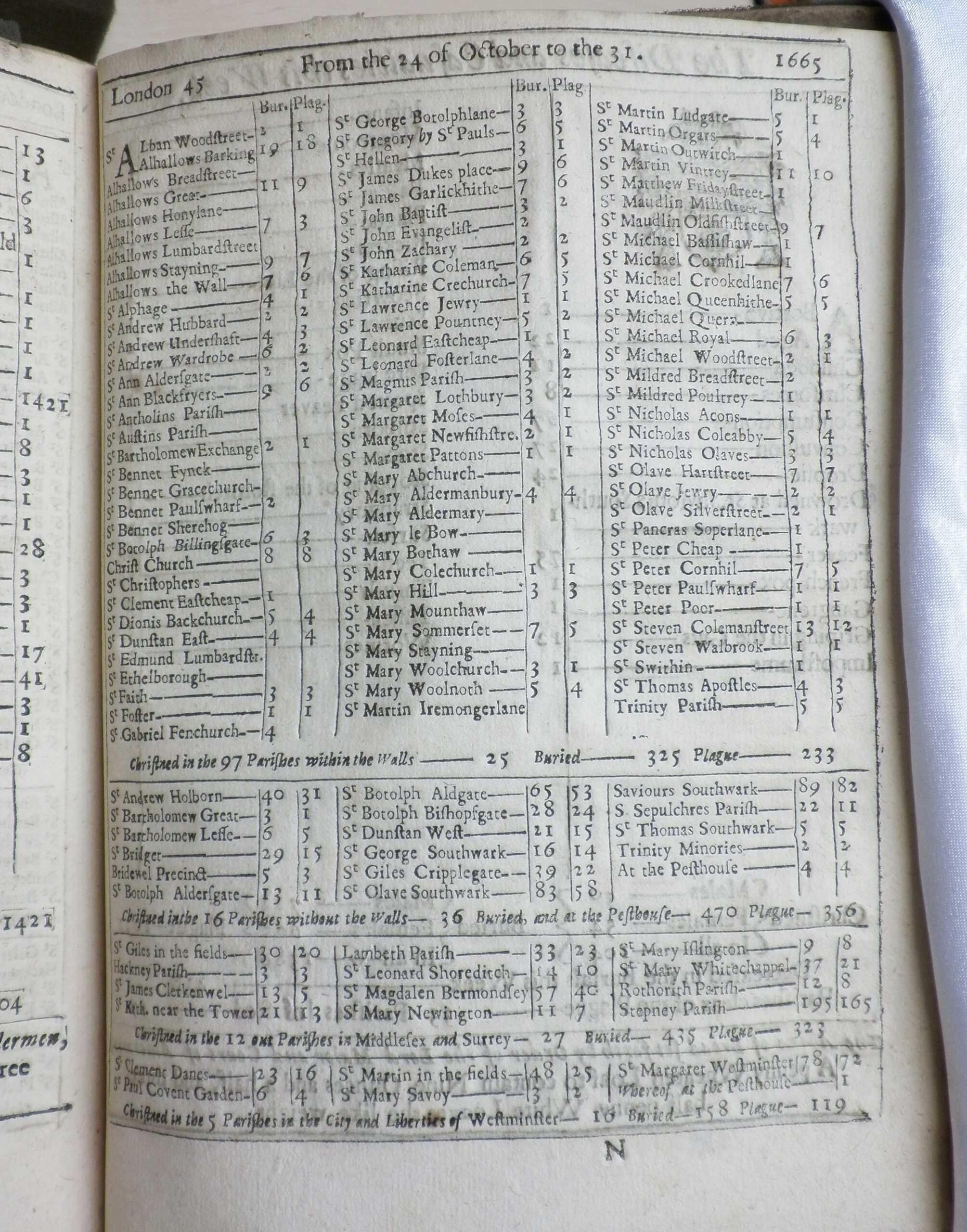

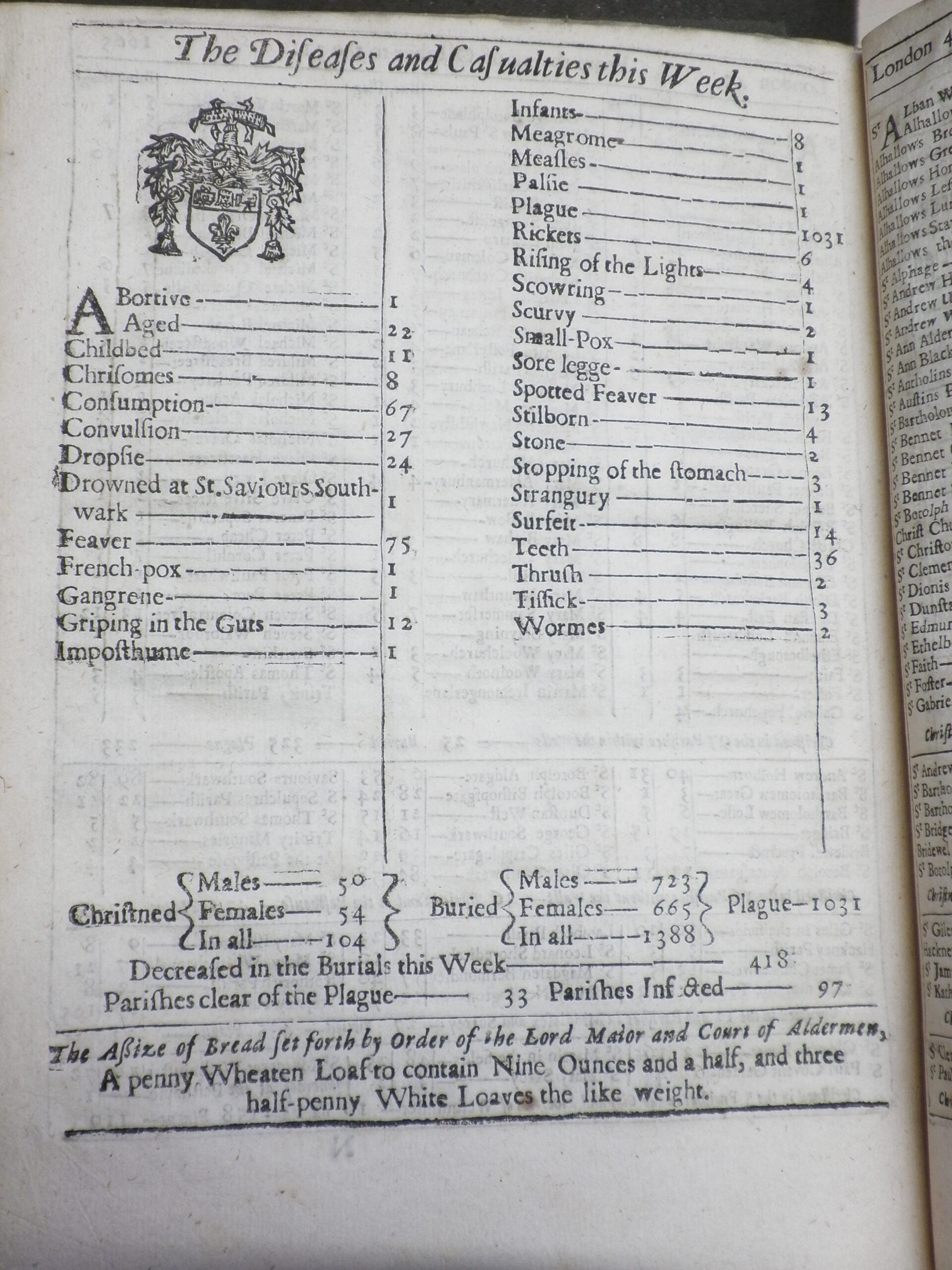

A grim publication provided the answer: London’s dreadful visitation: or, A collection of all the bills of mortality for this present year, beginning the 27th of December 1664. and ending the 19th. of December following. This catalogue of deaths illustrates the impact of the plague year on the population of London. The summary bound in at the back of the volume, A general bill for this present year, ending the 19 of December 1665 according to the report made to the kings most excellent majesty notes that of the 97,306 persons buried in the parishes of London in this period, 68,596 (70%) died of the plague.

Unusually for a time when printing was heavily controlled (for fear of the seditious ideas to which the printing press could give wing), in 1625 the Company of Parish Clerks were authorized to set up their own printing press (Adams, The parish clerks…, page 55). They had, however, to provide a bond of £500 to the Stationers’ Company, stating that they would not use the press for any purpose other than the production of the bills. In 1665, the Printer to the Company of Parish Clerks was ‘E. Cotes living in Aldersgate-street’. Ellinor (or sometimes Ellen) Cotes was the widow of the printer Richard Cotes, who had taken over his brother Thomas’ printing shop when Thomas died in 1641. Ellinor then took over the shop when Richard died in 1652 and was active until at least 1670. Hers was a reasonably large shop for the time; according to the 1666 Hearth Tax Roll, she had 3 presses, 9 pressmen, and 2 apprentices (see the British Book Trade Index). She has produced a grim, but informative pamphlet with a ghoulish woodcut border of skeletons, skulls, and the tools of the gravedigger, all under a ‘Memento Mori’ banner and a winged hourglass. These are fitting symbols for a time when the plague could rip through the city, killing at its worst 7,165 in a single week (the 12th-19th September 1665).

Mark Bainbridge, Librarian

Bibliography

- Adams, R., The parish clerks of London (London and Chichester: Phillimore, 1971)

- British Book Trade Index, available online at http://bbti.bodleian.ox.ac.uk

- MacGregor, N., Shakespeare’s restless world (London: Allen Lane, 2012)