Marks of a Magus

31st March 2016

Marks of a Magus

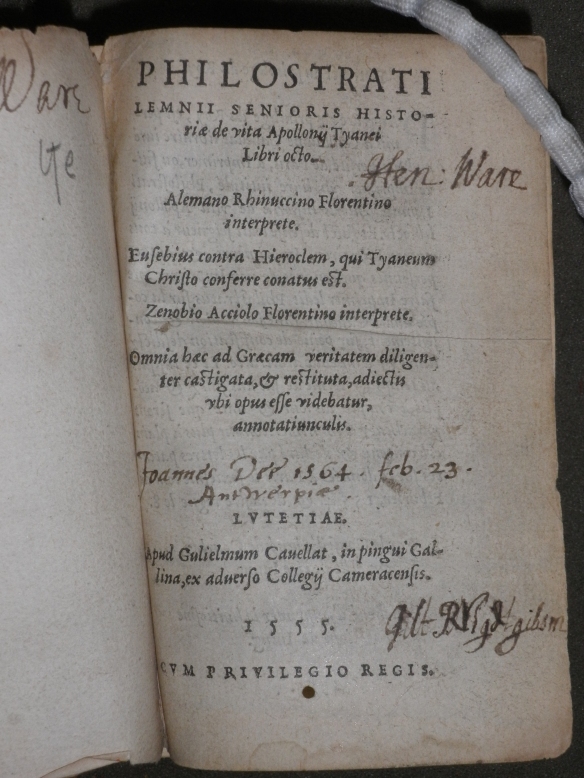

John Dee’s Philostratus (Paris, 1555)

Philostrati Lemnii senioris historiae de vita Apollonij Tyanei libri octo. Alemano Rhinuccino Florentino interprete. Eusebius contra Hieroclem, qui Tyaneum Christo conferre conatus est. Zenobio Acciolo Florentino interprete. Omnia haec ad Graecam veritatem diligenter castigata, & restituta, adiectis vbi opus esse videbatur annotatiunculis.

Lutetiae: apud Gulielmum Cauellat, in pingui Gallina, ex adverso Collegij Cameracensis, 1555.

[32], 634 pages; sextodecimo

Several recent visitors to Worcester College Library have come not to see particular texts for their own sake, but to consult them for the marks left by earlier owners, be they Inigo Jones’ marginalia on his copies of early architectural treatises, or the reading marks of early modern women on Tudor and Stuart works of travel literature. The ‘history of reading’ has grown as a subject in recent decades and among early modern readers individuals whose reading practices have received much attention include Inigo Jones, Ben Jonson, and the antiquary and politician Sir Robert Cotton (1571-1631) (see Sherman, ‘What did Renaissance readers write in their books?’, pages 119-120). Worcester’s connection with Inigo Jones is well known, but the College Library also has a volume that once belonged to another well-known early modern reader: the Elizabethan mathematician, astrologer, and antiquary, John Dee (1527-1609; see http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/7418?docPos=1).

John Dee performing an experiment before Queen Elizabeth I. Oil Painting by Henry Gillard Glindoni. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution, Non-commercial license CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

Dee, although often characterized as a ‘magus’ or sorcerer, was a scholar with wide-ranging intellectual interests (see Woudhuysen in TLS, January 29, 2016). According to his own claims he owned a library of 3,000 printed books and 1,000 manuscripts, one of the most significant private libraries of sixteenth-century England. Whilst many volumes have since been lost, before setting off for Poland in 1583 Dee made two manuscript catalogues; one of these catalogues, now at Trinity College, Cambridge (O.4.20) was published in facsimile by J. Roberts and A. G. Watson in 1990. On page 63 of the Trinity copy (see http://trin-sites-pub.trin.cam.ac.uk/james/viewpage.php?index=773) and listed as item 1217 in Roberts and Watson’s facsimile is Dee’s copy of Philostrati Lemnii senioris historiae de vita Apollonii Tyanei libri octo …, published in Paris by Guillaume Cavellat in 1555: it is a Latin translation of the Greek text of Philostratus’ Life of Apollonius of Tyana and now sits on the shelves of Worcester College Library, with Dee’s signature on the title page, noting that he picked it up at Antwerp on 23rd February 1564.

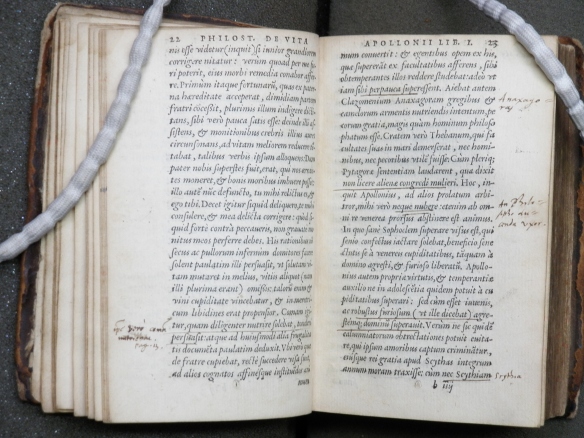

The Life of Apollonius of Tyana is Philostratus’ ‘longest work, and also the one that had the greatest resonance’ (Jones in his Loeb edition of Philostratus, pages 2-3). Published after AD 217 and perhaps dating to the 220s or 230s, it is a biography with novelistic touches of Apollonius, a first-century AD itinerant Pythagorean philosopher. It is tempting to draw parallels between Dee and Apollonius; indeed, the following description of the latter from the second chapter of Philostratus could easily be applied to Dee: ‘… some think him a sorcerer and misrepresent him as a philosophic imposter ’ (Philostratus, Apollonius I.2, from the Loeb translation by Christopher Jones). In the Latin translation owned by Dee, part of this passage has been underlined (pages 3-4):

It is difficult to say quite what is meant by these underlinings: Sherman notes that Roberts and Watson are right to point out that, taken individually, ‘the notes are rarely more than an expression of interest and seldom a record of opinion’ (Roberts and Watson quoted in Sherman, John Dee, page 80). Nonetheless, this Worcester volume provides further evidence of Dee’s extensive use of annotation – a huge number of his books contain marginalia (see Sherman, John Dee, page 80). In the Philostratus there is extensive underlining in the first part of the book, between pages 2 and 38, and then in the final section, with Dee occasionally adding marginalia in his fine italic hand: he structures the text with proper names in the margins, an ‘X’ marking particular passages, and references back and forth to other passages.

Dee’s ownership inscription shows that he bought the book in Antwerp on 23rd February 1564. At the end of 1562, Dee had travelled to Europe, visiting Antwerp, Padua, Venice and Urbino, attending the coronation of Maximilian II as King of Hungary at Pressburg (Bratislava) in September 1563, before returning to England via Antwerp. This copy of Philostratus is one of several book purchases attesting to his presence in Antwerp until June 1564.

Dee’s extensive Library was partly dispersed after his departure for Poland in 1583, with some of the books almost certainly being stolen. It is possible that this Philostratus was among the latter although it does not bear the signature of Nicholas Saunder, who received many of Dee’s stolen books (see Roberts and Watson). Only two further provenance marks are visible on the title page: that of Henry Ware (b. 1688 – the binding bears his armorial stamp of two lions passant surrounded by eight escallops, for which see http://armorial.library.utoronto.ca/stamps/WAR004_s2) and an unread signature of, perhaps, ‘Gil[ber]t ????gibson’. From the Worcester stamp on its front paste-down, it is likely that it came to Worcester College Library as one of the purchases of Henry Allison Pottinger (1824-1911), Librarian from 1884 until 1911. Pottinger was a prolific and wide-ranging bibliophile and his collecting has led to the presence of several items such as Dee’s Philostratus that readers are surprised to find on the shelves of Worcester College Library.

Mark Bainbridge, Librarian

Bibliography

- Philostratus, The life of Apollonius of Tyana, edited and translated by Christopher P. Jones (Cambridge, MA and London, 2005)

- Roberts, J. and Watson, A. G. (eds.), John Dee’s library catalogue (London, 1990)

- Sherman, W. H., John Dee: the politics of reading and writing in the English Renaissance (Amherst, 1995)

- Sherman, W. H., ‘What did Renaissance readers write in their books?’, in Andersen, J. and Sauer, E., Books and readers in early modern England: material studies (Philadelphia, 2002), pages 119-137

- Woudhuysen, H. R., ‘Mony mony’ (review of ‘Scholar, Courtier, Magician: the lost library of John Dee’, Royal College of Physicians, until July 29), Times Literary Supplement, no. 5887, 29 January 2016