Illustrating Ovid

31st July 2019

Illustrating Ovid

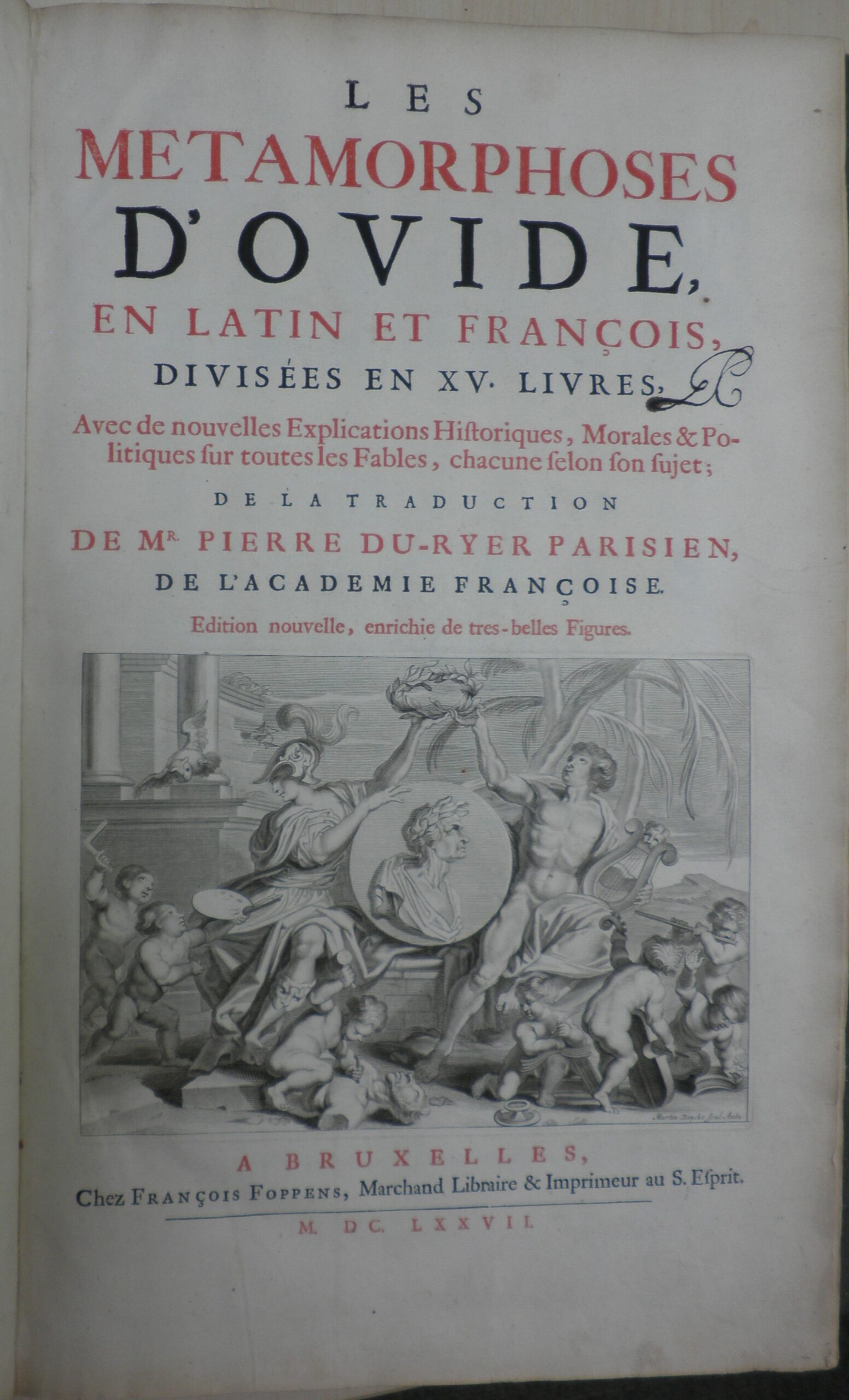

Les metamorphoses d’Ovide, : en latin et françois, divisées en XV. livres, avec de nouvelles explications historiques, morales & politiques sur toutes les fables, chacune selon son sujet

Edition nouvelle, enrichie de tres-belles figures

A Bruxelles: Chez François Foppens, 1677

In the middle of the vacation we have decided to go for an image-heavy treasure and in searching our collections we naturally gravitated towards texts of Ovid, perhaps the ‘most important literary source’ for mythological subjects in works of Renaissance art (see Allen, ‘Ovid and art’, page 336). From the collection gifted in 1736 by George Clarke, we found a luxury folio volume, 49-cm high, bound in creamy vellum, which contains 124 engravings illustrating the stories of Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

The French text is the translation by the dramatist Pierre Du Ryer (1606-1658), ‘one of the most frequently reprinted editions of the Metamorphoses in this period’ (Taylor, ‘Translating lives…’), and to it has been added ‘The Judgement of Paris’ by Nicolas Renouard, as well as Renouard’s translation of selected letters from Ovid’s Heroides.

Whilst the authors of the translation and additional texts are easily identifiable, the printers responsible for the plates are less so. Only three have signed their work: Peter Paul Bouché (for example, on page 249), Martin Bouché (page 362) and Frederic Bouttats (page 288).

Bouttats, Callisto turned into a bear (from page 288)

The work of these Flemish printers, who worked in the mid- to late 17th century (Peter Paul Bouché was born about 1646; Martin Bouché worked between 1640 and 1693; Bouttats lived between 1610-1675 – see https://collections.mfa.org/objects/440818) is accompanied by prints from an earlier generation of printers, the de Passe family, originally of Antwerp, but active in various European cities between 1564 and 1670 (see Veldman, Crispijn de Passe and his progeny). Many are the work of the talented daughter of the house, Magdalena de Passe (1600-1638), whose work employs a delicate style and subtle chiaroscuro – see for example, her engraving of Juno and Semele (page 88).

Magdalena de Passe, ‘Juno and Semele’ (from page 88)

As Henkel suggests (Henkel, ‘Illustrierte Ausgaben von Ovids Metamorphosen…’), the de Passe engravings were produced in the early 17th century for a publication that remained unpublished; in 1677 a different publisher, Foppens, therefore supplemented them with work by other artists to complete the set. This has resulted in a stylistic contrast between prints produced at different periods. The contrast is further caused by the variety of artists whose paintings have been used as the models for some prints, artists such as Rubens (see pages 36 and 202), Rembrandt (page 83), Abraham van Depienbeeck (page 473) and others (van der Waals provides a useful list in his De Prentschat van Michiel Hinloopen, pages 79-95). As we noted at the start of this piece, Ovid was a popular source for artists in the Renaissance and later, and their work has clearly influenced the plates in this publication. For example, Cadmus’ encounter with the dragon (page 79) is clearly modelled on ‘Two Followers of Cadmus devoured by a Dragon’ (1588) by Cornelis van Haarlem (see https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/cornelis-van-haarlem-two-followers-of-cadmus-devoured-by-a-dragon).

‘Cadmus and the dragon’, after Haarlem (from page 79)

‘Apollo flaying Marsyas’ (page 190) is a copy of the c. 1633 painting by Guido Reni (see https://www.sammlung.pinakothek.de/en/artist/guido-reni/apoll-schindet-marsyas).

‘Apollo flaying Marsyas’, after Guidi Reni (from page 132)

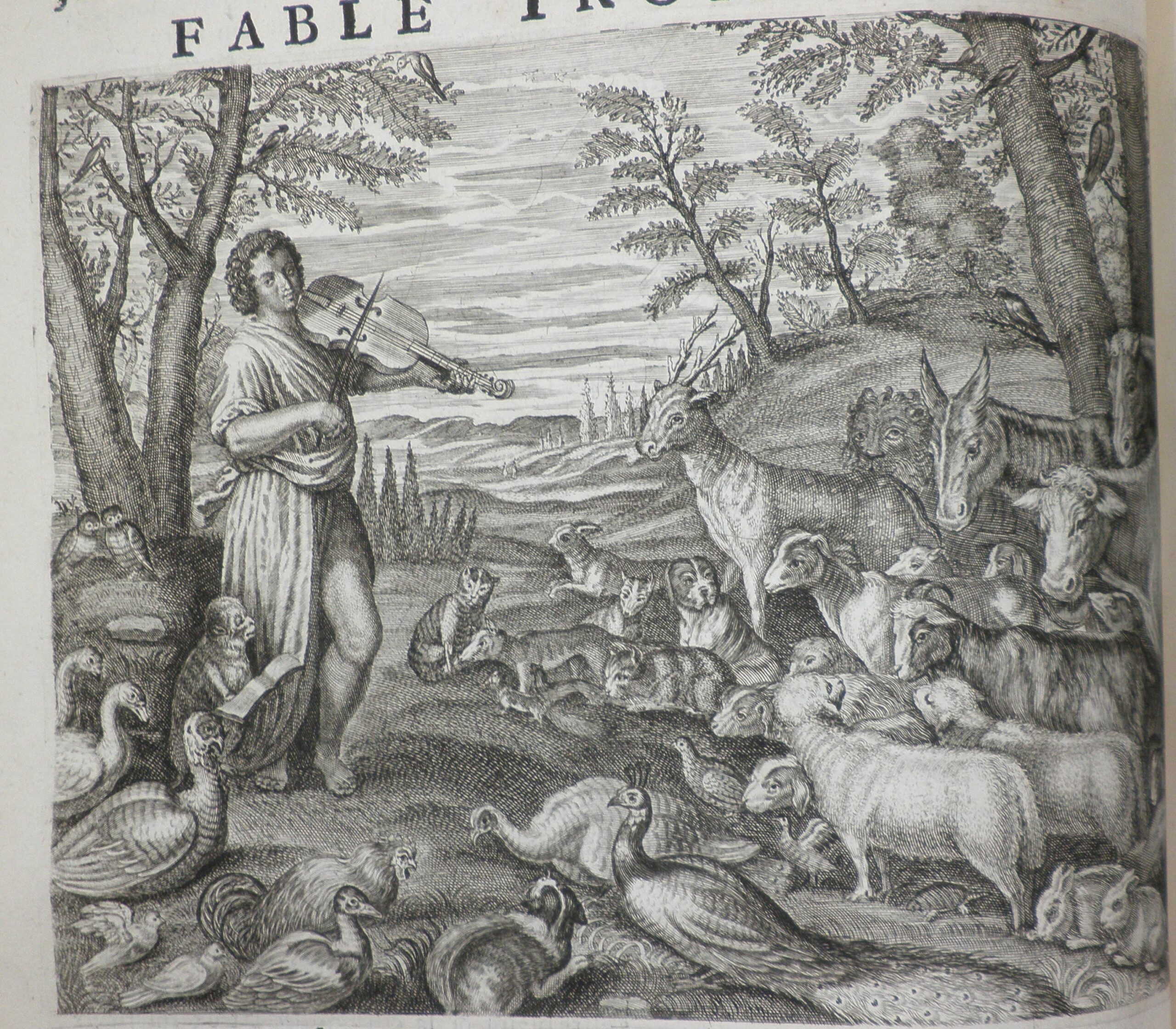

Finally, ‘Orpheus charming the animals’ (page 312), is after the painting by Leandro da Ponte Bassano (see http://www.artnet.com/artists/leandro-da-ponte-bassano/orpheus-charming-the-animals-kPn9npYSU4lEltm4z8XOcA2).

‘Orpheus charming the animals’, after Leandro da Ponte Bassano (from page 190)

The Metamorphoses contains over 250 narratives (Galinsky, Ovid’s Metamorphoses, page 4) and with just under half illustrated by this volume’s 124 engravings, there is much to divert one in this volume. Although an illustrated volume and not technically a set of prints (see Clayton, ‘The print collection of George Clarke…’, page 137, for this distinction), one can well imagine George Clarke, the keen print collector, enjoying this volume for its variety of images as well as for the text of Ovid – a perfect diversion for summer months!

Mark Bainbridge, Librarian

Bibliography

- Allen, ‘Ovid and art’, in P. Hardie (ed), The Cambridge companion to Ovid (Cambridge: CUP, 2002)

- Clayton, T. ‘ The print collection of George Clarke at Worcester College, Oxford’, Print Quarterly IX (1992), issue 2, pages 123-141

- Galinsky, G. K., Ovid’s Metamorphoses: an introduction to the basic aspects (Oxford: Blackwell, 1975)

- Henkel, M. D., ‘Illustrierte Ausgaben von Ovids Metamorphosen im XV., XVI., und XVII. Jahrhundert’, Vorträge der Bibliothek Warburg 1926-1927 (Leipzig/Berlin, 1930), pages 118-126

- Taylor, H., ‘Translating Lives: Ovid and the Seventeenth-Century Modernes’, Translation and literature, volume 24, issue 2 (2015), pages 147-171

- van der Waals, De prentschat van Michiel Hinloopen : Een reconstructie van de eerste openbare papierkunstverzameling in Nederland (Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, 1988)

- Veldman, I. M., Crispijn de Passe and his progeny (1564-1670): a century of print production (Rotterdam: Sound and vision, 2001)