Gardening for Ladies

29th September 2017

Gardening for Ladies

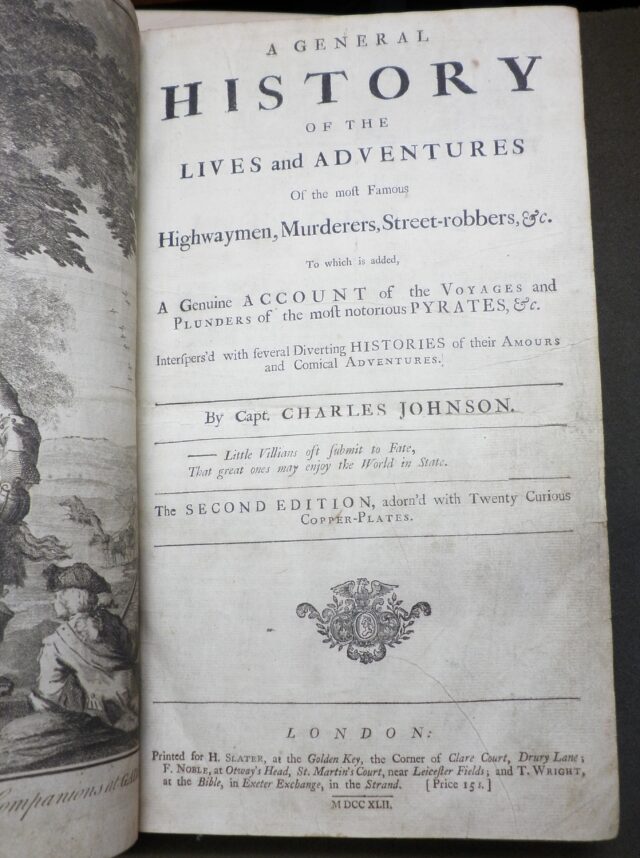

The Ladies’ Flower-Garden of Ornamental Annuals. By Mrs. Loudon.

London: William Smith, 113 Fleet Street, MDCCCXL

xvi, 272 pages, folio

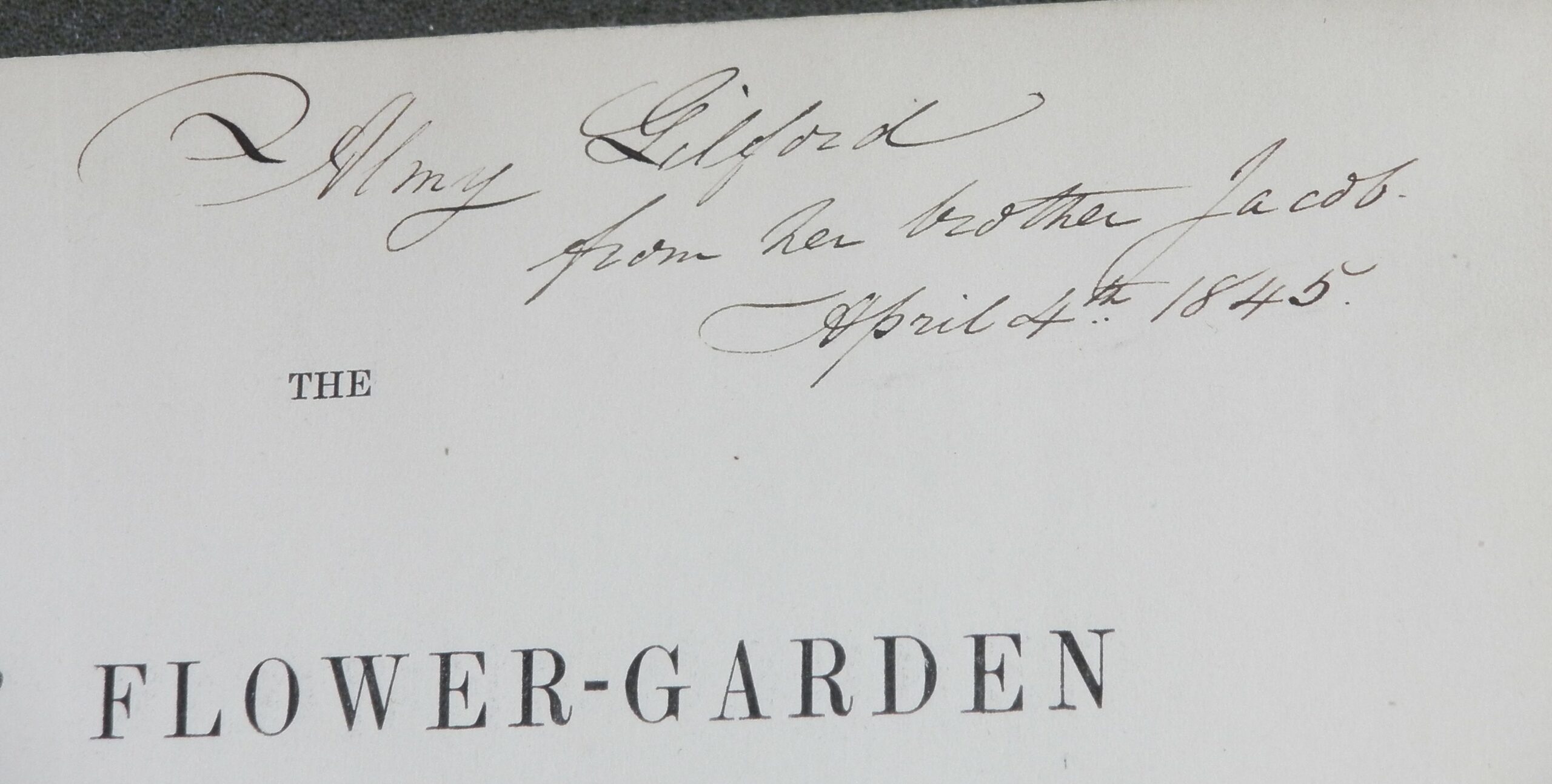

One of the joys of working in a historic library is when one happens upon an unexpected and surprising book on the shelves. The Ladies’ Flower-Garden of Ornamental Annuals is just such a discovery. Resting comfortably in the back corner of our book stack, The Ladies’ Flower-Garden has a shelfmark, but is not in any of our catalogues, print or online. The state of its binding suggests that it has been well used, but as a popular gardening manual aimed at women, it does not seem like something which a nineteenth-century college librarian would have acquired for the library. The only evidence of provenance is an inscription marking the book as a gift from a brother to his sister in 1845.

Neither Jacob nor Almy Gilford are known to be associated with Worcester College, so we can assume that the book likely changed hands at least once before finding its way into our collections. It is possible that it was one of the books left to the library by Henry Allison Pottinger, Librarian of Worcester from 1884-1911 and an eclectic collector, or it may have come from a later donation. Its shelfmark places it in a section that is best described as ‘miscellaneous’; a section for books that don’t seem to fit anywhere else.

For those of us without green fingers, an encyclopaedia of ornamental annuals does not inspire much excitement, but the history of the Ladies’ Flower-Garden and its author is also surprising. Jane Webb Loudon was born in 1807, the daughter of a businessman. She was orphaned at the age of 17 and took up writing to support herself. She wrote both fiction and educational works, but her most notable work before her marriage was The Mummy! A Tale of the Twenty-Second Century, published in 1827 and described as a ‘pioneering work of science fiction’ by Ann Shteir (Sarah Dewis, The Loudons and the Gardening Press, p. 196; Ann Shteir, ‘Loudon, Jane’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography). At the centre of the plot is the ‘reanimation of an Egyptian mummy by galvanism’ and the story is filled with futuristic inventions, some of which seem to anticipate modern technology: ‘a system of air-conditioning’, air mattresses, espresso machines, steam shovels, and milking machines (John Gloag, Mr. Loudon’s England, p. 59). The book caught the attention of John Claudius Loudon (1783-1843), a well-known landscape gardener and horticultural writer, who reviewed it for the Gardener’s Magazine (of which he was editor) and sought to make the acquaintance of the author, whom he assumed to be male (Shteir, ODNB). Presumably he was not disappointed in the discovery that Jane was in fact female, as after meeting in February 1830, he married her within the year.

Before marrying John, Jane had no knowledge of botany or horticulture, but she threw herself wholeheartedly into the subject. She attended lectures on botany and accompanied John on tours of the country, acting as his secretary. She assisted with his publications and began writing for the Gardener’s Magazine (Shteir, ODNB). John Loudon was an energetic and prolific writer, but also an ambitious one and the production of his Arboretum (1838), an extensively illustrated, eight-volume technical work on the trees and shrubs of Britain, left the Loudons with substantial debts (Gloag, Mr. Loudon’s England, p. 64; Dewis, The Loudons, pp. 117-118). So Jane began to write her own gardening books to support the family, aimed instead at non-specialists, and more specifically, women. In 1840 she published Instructions in Gardening for Ladies, which sold 1,350 copies on the day of publication (Shteir, ODNB). This was followed by the Ladies’ Flower-Garden series (which includes volumes on ornamental annuals, bulbous plants, perennials, and greenhouse plants), The Ladies’ Companion to the Flower-Garden (1841), Botany for Ladies (1842), and The Lady’s Country Companion, or, How to Enjoy a Country Life Rationally (1845), among others. The Ladies’ Companion to the Flower-Garden sold 20,000 copies over nine editions and The Ladies’ Flower-Garden series has been reprinted frequently (Dewis, The Loudons, p. 203; Shteir, ODNB).

The Ladies’ Flower-Garden of Ornamental Annuals is an encyclopaedia designed to introduce women to the variety of flowers which can be cultivated in their gardens. Each entry lists the botanical and English names of the flower, followed by descriptions, history, folklore, and instructions for cultivation. Although the book is aimed at non-specialists, Webb Loudon does not skimp on the technical aspects of botany and horticulture, instead offering a glossary of botanical terminology to help the uninitiated. It is well illustrated with colour lithographic plates, depicting groups of flowers arranged by John Lindley’s ‘Natural System’ (Webb Loudon was a devotee of Lindley, having attended his public lectures soon after her marriage). There is also a substantial bibliography at the end, to provide suggestions for further reading.

Jane Webb Loudon has been credited with making gardening into a respectable activity for middle-class women. Traditionally, gardening had been the preserve of the aristocracy and great landowners but by the early nineteenth-century, gardening was becoming a middle-class activity as well (Sue Bennett, Five Centuries of Women & Gardens, p. 82; for more see in particular Heath Schenker’s article ‘Women, gardens, and the English Middle Class in the Early Nineteenth Century’). Webb Loudon’s writings sought to open up the world of gardening to other women who, generally lacking the formal and scientific education given to men of their class, might find the more academic treatises on gardening inaccessible. In the introduction to Gardening for Ladies she writes:

‘I write this because I think books intended for professional gardeners are seldom suited for the needs of amateurs… Having been a full-grown pupil myself, I know the wants of others; and having never been satisfied without grasping the reason for everything that had to be done, I am able to interpret these reasons to others.’ (quoted in Bennett, Five Centuries of Women & Gardens, p. 91)

She also portrayed gardening, particularly flower-gardening, as an activity eminently suitable for ‘gently bred’ ladies. In the introduction to The Ladies’ Flower-Garden she writes of growing ornamental plants:

‘…the easiness of their culture renders it peculiarly suitable for a feminine pursuit. The pruning and training of trees, and the culture of culinary vegetables, require too much strength and manual labour ; but a lady, with the assistance of a common labourer to level and prepare the ground, may turn a green waste into a flower-garden with her own hands. Sowing the seeds of annuals, watering them, transplanting them when necessary, training the plants by tying them to little sticks as props, or by leading them over trellis-work, and cutting off the dead flowers, or gathering the seeds for the next year’s crop, are all suitable for feminine occupations ; and they have the additional advantage of inducing gentle exercise in the open air.’ (p. i)

It is clear that Webb Loudon, while progressive in her views on women’s education by nineteenth-century standards, was not a radical when it came to gender roles. She believed in the value of science education for women, but also espoused the Victorian ideal of ‘separate spheres’, where a woman’s place was in the ‘private sphere’ of the home, and clearly envisioned her readers as middle class women who would have male servants to do the heavy lifting of gardening (Dewis, The Loudons, p. 228; Schenker, ‘Women, gardens…’, pp. 352-354). However Heath Schenker has argued that she sought to expand the boundaries of the private sphere to include the garden as a place where women could exercise influence (Schenker, ‘Women, gardens…’, p. 359).

The success of her publications demonstrates that there was clearly an appetite among her peers for accessible garden writing. We will likely never know for certain how our copy of the Ladies’ Flower-Garden found its way to Worcester College, but it is easy to imagine its previous owners spending long winter evenings examining the beautifully coloured plates of flowers and planning for spring.

Renée Prud’Homme, Assistant Librarian

Bibliography

- Bennett, Sue, Five Centuries of Women and Gardens (London: National Portrait Gallery, 2000)

- Dewis, Sarah, The Loudons and the Gardening Press: A Victorian Cultural Industry (Farnham: Ashgate, 2014)

- Gloag, John, Mr. Loudon’s England (Newcastle: Oriel Press, 1970)

- Schenker, Heath, ‘Women, gardens, and the English Middle Class in the Early Nineteenth Century’ in Bourgeois and Aristocratic Cultural Encounters in Garden Art, 1550-1850, ed. Michael Conan (Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2002)

- Shteir, Ann B., ‘Loudon, Jane (1807-1858)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press 2004), [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/17030, accessed 8 Sept 2017]

- Simo, Melanie Louise, Loudon and the Landscape: From Country Seat to Metropolis (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988)