‘But here it is indeed…we have a new World discovered’

16th December 2016

‘But here it is indeed…we have a new World discovered’

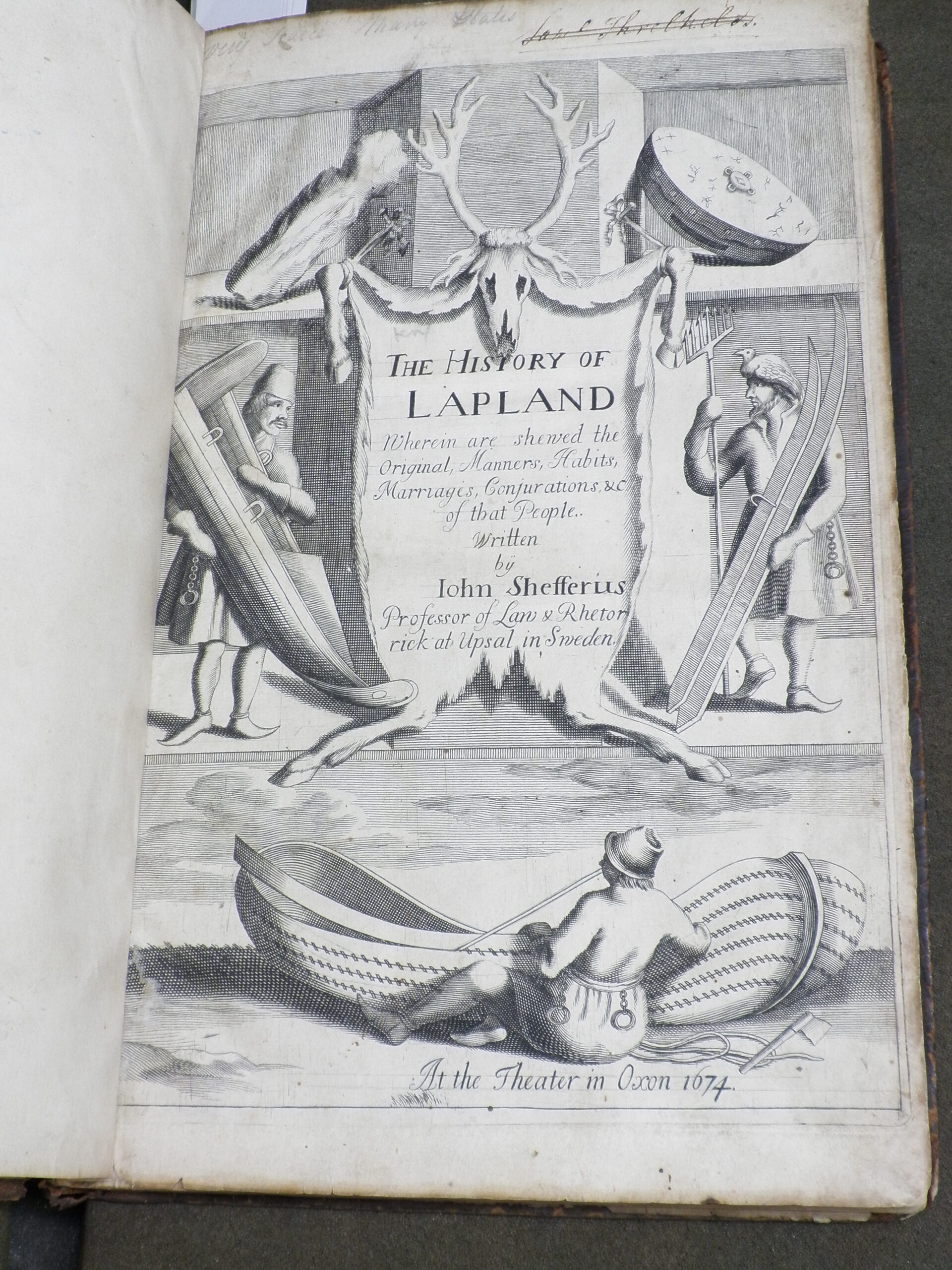

The History of Lapland, wherein are shewed the Original, Manners, Habits, Marriages, Conjurations, &c. of that People, written by John Scheffer

Oxford: At the theater, 1674.

This month, as the nights lengthen and the cold settles in, we look to the north for our treasure of the month. The History of Lapland was first published in Latin in Frankfurt in 1673 and was translated and published in English in Oxford in 1674. It was written by Johannes Schefferus, Skyttean Professor at the University of Uppsala in Sweden. Schefferus (1621-1679) was originally from Strasbourg, but in 1648 was invited by Queen Kristina of Sweden to take up the professorship at Uppsala, where he spent the rest of his life (Sjoholm, ‘Lapponia’, p. 9). Through his work on Swedish antiquarianism and archaeology, among other areas, he went on to become a significant figure in Swedish cultural and academic history. The History of Lapland is his best-known work.

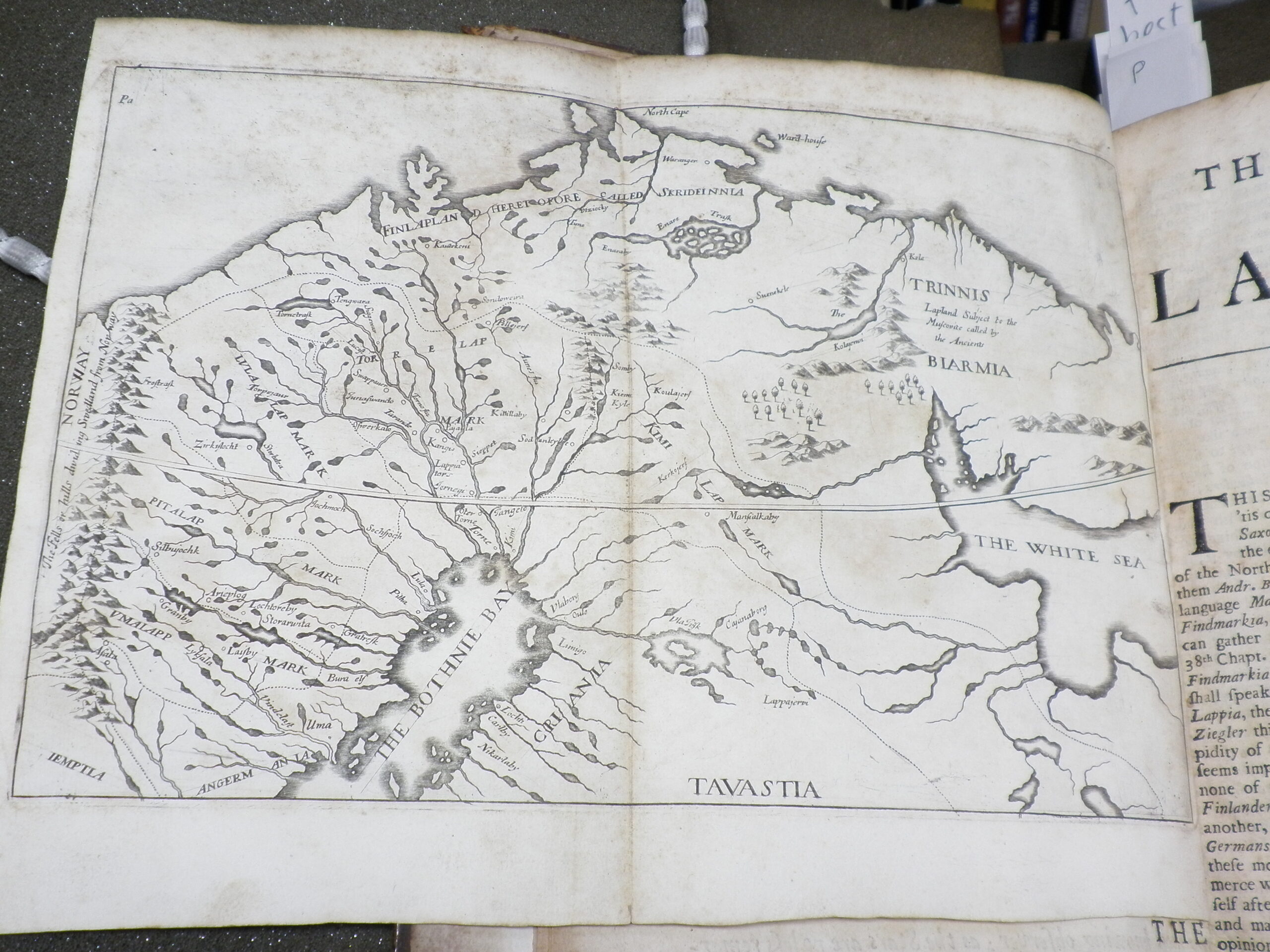

Map of Lapland, or Sápmi.

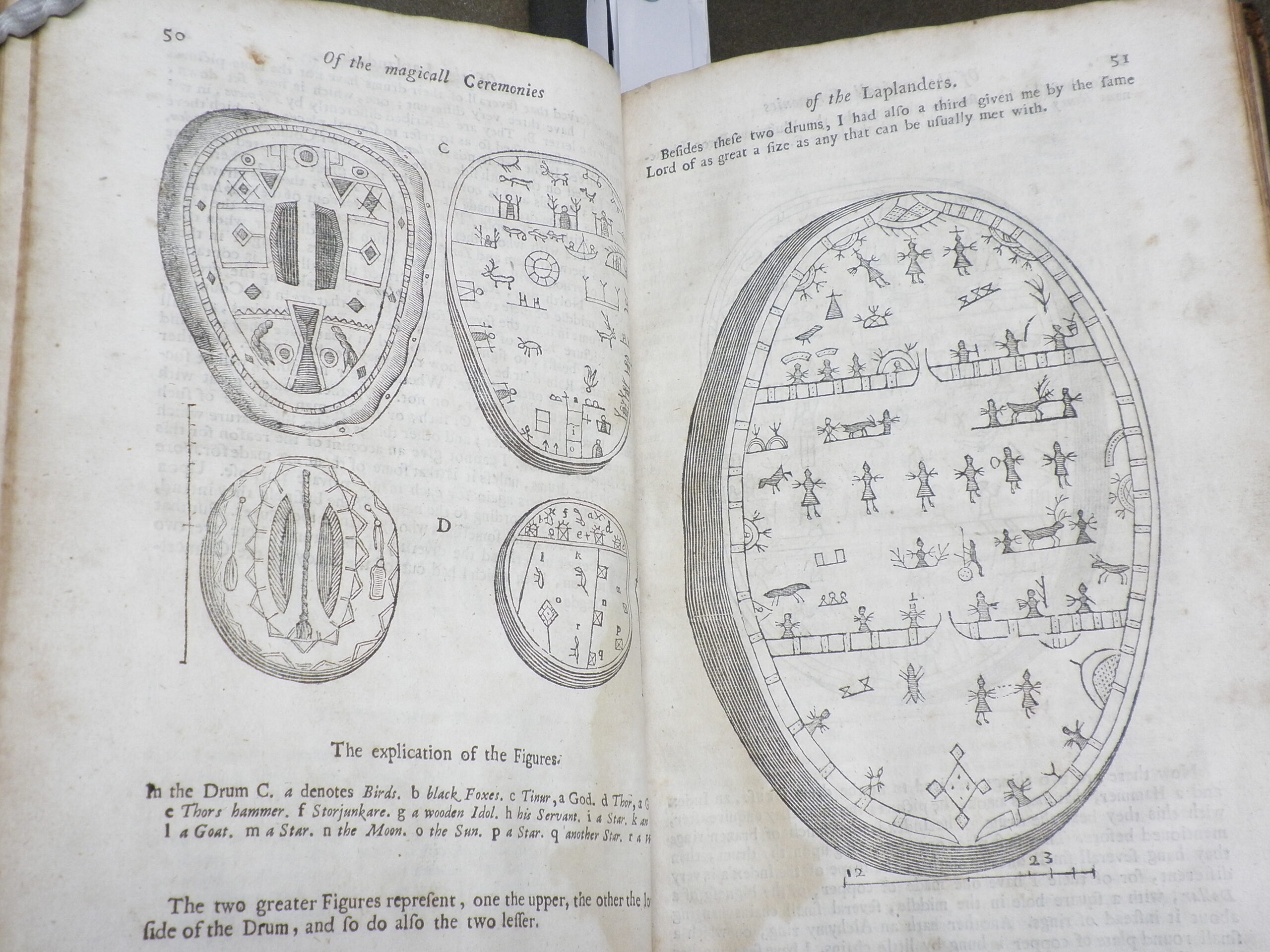

The History of Lapland is a study of the Sami people of northern Scandinavia (a region known to the Sami as Sápmi and in English generally as Lapland). Schefferus’ work looks at many aspects of Sami life and culture, as well as the landscape and region more generally. The book is made up of 35 chapters on topics ranging from language and garments to ‘magicall ceremonies’ and ‘rain-deers’. Schefferus himself never travelled to Lapland but instead depended on accounts written by contacts in northern Sweden, primarily clergymen, and on Sami objects in private collections (Manker, ‘Swedish Contributions’, p. 39; Sjoholm, ‘Lapponia’, p. 9). The book is illustrated with numerous woodcuts from drawings done by Schefferus (Sjoholm, ‘Lapponia’, p. 11). These fascinating images show Sami clothes and homes, as well as many uses for reindeer and

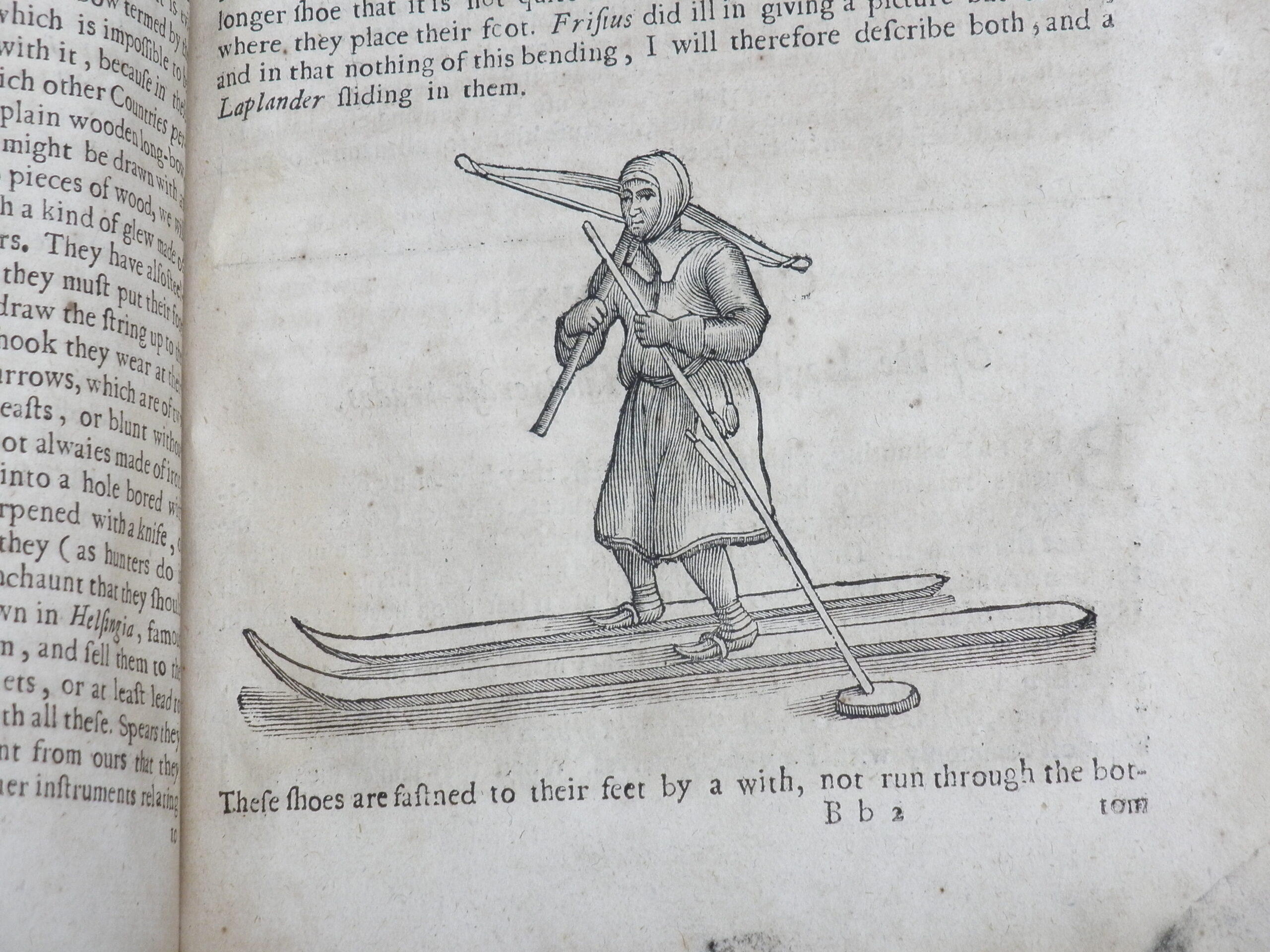

‘other instruments relating to [hunting], the chiefest of which are their shoes, with which they slide over the frozen snow, being made of broad planks extremely smooth; the Northern People call them Skider, and by contraction, Skier…’ (Schefferus, The History of Lapland, p. 99)

A hunter on ‘skider’ (p. 99)

Using a reindeer to pull a sledge.

The impetus for the publication of The History of Lapland came from Magnus De la Gardie, chancellor of both the nation and Uppsala University at this time. De la Gardie was keenly interested in antiquities and academic research (Stomberg, A History of Sweden, p. 432). He wasn’t alone – culture was all the rage in seventeenth-century Sweden. After a series of military victories, Sweden was at its peak as a European power. This newfound position of prominence spurred monarchs and prominent members of society to build Sweden’s cultural as well as military standing. Earlier in the century, King Gustavus Adolphus developed the nation’s school system and endowed the University of Uppsala. Mid-century, Queen Kristina invited foreign scholars to her court and the university. Interest in Swedish antiquities grew, as did a taste for a romanticized, nationalist history in which Sweden appeared as the ‘mother of nations’ in Europe, though Schefferus was known for a more critical approach (Ellenius, ‘Johannes Schefferus’, p. 60; Stomberg, History of Sweden, p. 432; Lindroth; A History of Uppsala University, p. 75, p. 48). In 1666 De la Gardie helped found the Collegium Antiquitatum, of which Schefferus was a member, to further the study of Swedish antiquities, including language, manuscripts, archaeology, numismatics, and genealogy (Ellenius, ‘Johannes Schefferus’, p. 61).

But aside from a general interest in Sweden’s topography and history, De la Gardie seems to have had a more specific intention in publishing a work on Lapland. According to Paine, ‘the enemies of Sweden, in apparent exasperation, had attributed her outstanding military successes to the magic devised before the battle by Lapps wilfully employed by Gustavus Adolphus’ (‘Review’, p. 52). De la Gardie sought to dispel these rumours by publishing a more accurate account of the Sami and their culture, with particular emphasis on their conversion to Christianity (Sjoholm, ‘Lapponia’, p. 9). Whether The History of Lapland achieved these goals is debateable. Despite being known for his critical analysis and methodology, Schefferus’ descriptions of the Sami were only as accurate as the second-hand accounts he received (Paine, ‘Review’, p. 52). And although The History of Lapland does discuss the conversion of the Sami to Christianity, it also goes into detail about the pre-Christian religion and customs of the Sami, some aspects of which had survived into the seventeenth-century, and these were the details that seemed to capture the public imagination. Bowdlerized versions appeared which excerpted chapters on non-Christian rituals (Sjoholm, ‘Lapponia’, p. 11) and other authors sometimes used Schefferus’ work with quite the opposite intention; John Beaumont, an English demonologist, quoted The History of Lapland at length in his 1705 work Treatise of Spirits, as evidence of the persistence of ‘demon-worship and demonic power’ (Seaton, Literary Relations, p. 215). Whatever the flaws and misuses of The History of Lapland, it was an extremely influential work and remained the dominant scholarly text on the Sami until well into the twentieth-century (Manker, ‘Swedish Contributions’, p. 39).

English readers, including the Royal Society, were particularly interested in Sami drum rituals (Seaton, Literary Relations, p. 253)

As well as being published in English in 1674, The History of Lapland was also published in German in 1675, French in 1678, and Dutch in 1682. Ironically, it was not published in Swedish until 1956. Correspondence of the Royal Society shows that Schefferus’ work was eagerly awaited in England (Seaton, Literary Relations, pp. 213-214), but English translation of the book came about in a rather unusual way. The university press in Oxford at that time was under the direction of Dr John Fell, Dean of Christ Church (and later bishop of Oxford), and it is his disciplinary practices that we have to thank for the English edition of The History of Lapland. Quoting the diarist Hearne, Falconer Madan tells us that:

‘The English translation… was made by Mr. Acton Cremer (who was then Bach. of Arts of Xt Church), being an Imposition set to him by Bp. Fell for courting a Mistress at yt age, which the Bp. dislik’d, yet for all that he married.’ (Oxford Books, p. 300)

Despite this harsh punishment, Cremer went on to marry the lady in question in 1676 (Madan, Oxford Books, p. 300). Fell was apparently pleased with the translation though and the book was printed by the university press, which was at that time was housed in the Sheldonian Theatre (hence the phrase ‘at the theater’ on the title page). For all that Fell was pleased with Cremer’s translation, it was rather incomplete. The original work contained many direct quotations in Swedish from Schefferus’ sources (Paine, ‘Review’, p. 52). These were left out of the English edition entirely as, according to the preface, ‘we suppose [the reader] would not have bin much edified by them’. Presumably they were unable to find a translator who spoke Swedish.

Fell did not skimp on illustrations however. He paid the engraver George Edwards £2 for 26 woodcuts for the work (Ould, ‘The Workplace’, p. 231). It is a great boon for the modern reader that he did as the illustrations can provide a glimpse, however limited, into a culture that was already rapidly changing at the end of the seventeenth-century.

Renée Prud’Homme, Assistant Librarian

*The title of this post is a quotation from the preface, ‘…but here it is indeed, where, rather than in America, we have a new World discovered: and those extravagant falsehoods, which have commonly past in the narratives of these Northern Countries, are not so inexcusable for their being lies, as that they were told without temtation; the real truth being equally entertaining, and incredible’.

Bibliography

- Ellenius, Allan, ‘Johannes Schefferus and Swedish Antiquity’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. 20 No. 1/2 (Jan. – Jun. 1957), pp. 59-74

- Hultkrantz, Åke, ‘Swedish Research on the Religion and Folklore of the Lapps’, The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 85 No. 1/2 (1955), pp. 81-99

- Lagerqvist, Lars O., A History of Sweden (Värnamo, 2001)

- Larminie, Vivian, ‘The Fell Era 1658-1686’ in The History of Oxford University Press Volume I: Beginnings to 1780, ed. Ian Gadd (Oxford, 2013)

- Lindroth, Sten, A history of Uppsala University 1477-1977 (Uppsala, 1976)

- Madan, Falconer, Oxford Books: A bibliography of printed works relating to the University and City of Oxford, or printed or published there, Vol. 3: Oxford Literature 1651-1680 (Oxford, 1931)

- Manker, Ernst, ‘Swedish Contributions to Lapp Ethnography’, The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 82 No. 1 (Jan. – Jun. 1952), pp. 39-54

- Ould, Martyn, ‘The Workplace: Places, Procedures, and Personnel 1668-1780’, in The History of Oxford University Press Volume I: Beginnings to 1780, ed. Ian Gadd (Oxford, 2013)

- Paine, Robert, ‘Review: Lappland by Johannes Schefferus, Henrik Sundin, John Granlund, Bengt Löw, Ernst Manker, John Granlund, John Bernström and Nordiska Museet’, Man, Vol. 58 (March 1958), p. 52

- Seaton, Ethel, Literary Relations of England and Scandinavia in the Seventeenth Century (Oxford, 1935)

- Sjoholm, Barbara, ‘Lapponia’, Harvard Review, No. 29 (2005), pp. 6-19

- Stomberg, Andrew, A History of Sweden (London, 1932)