An August Atlas

31st August 2016

An August Atlas

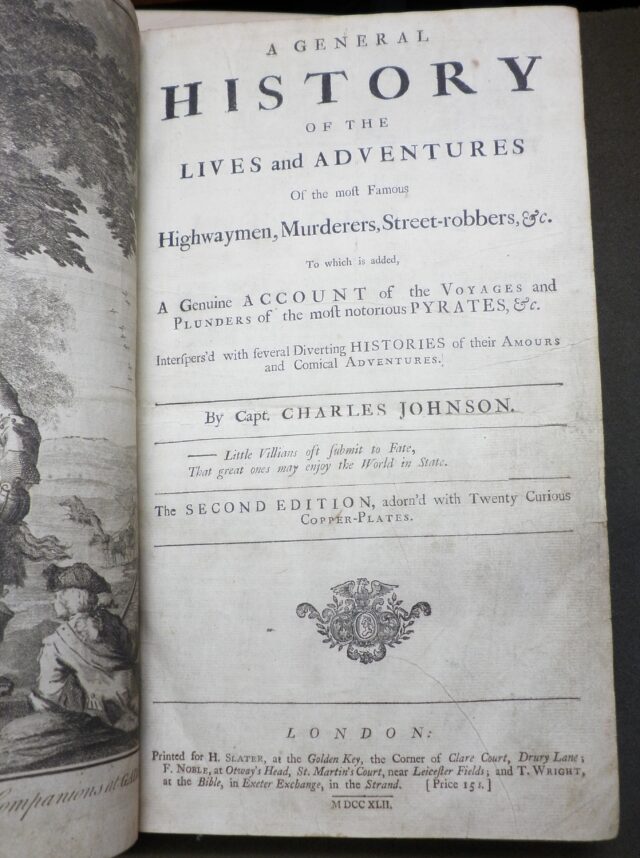

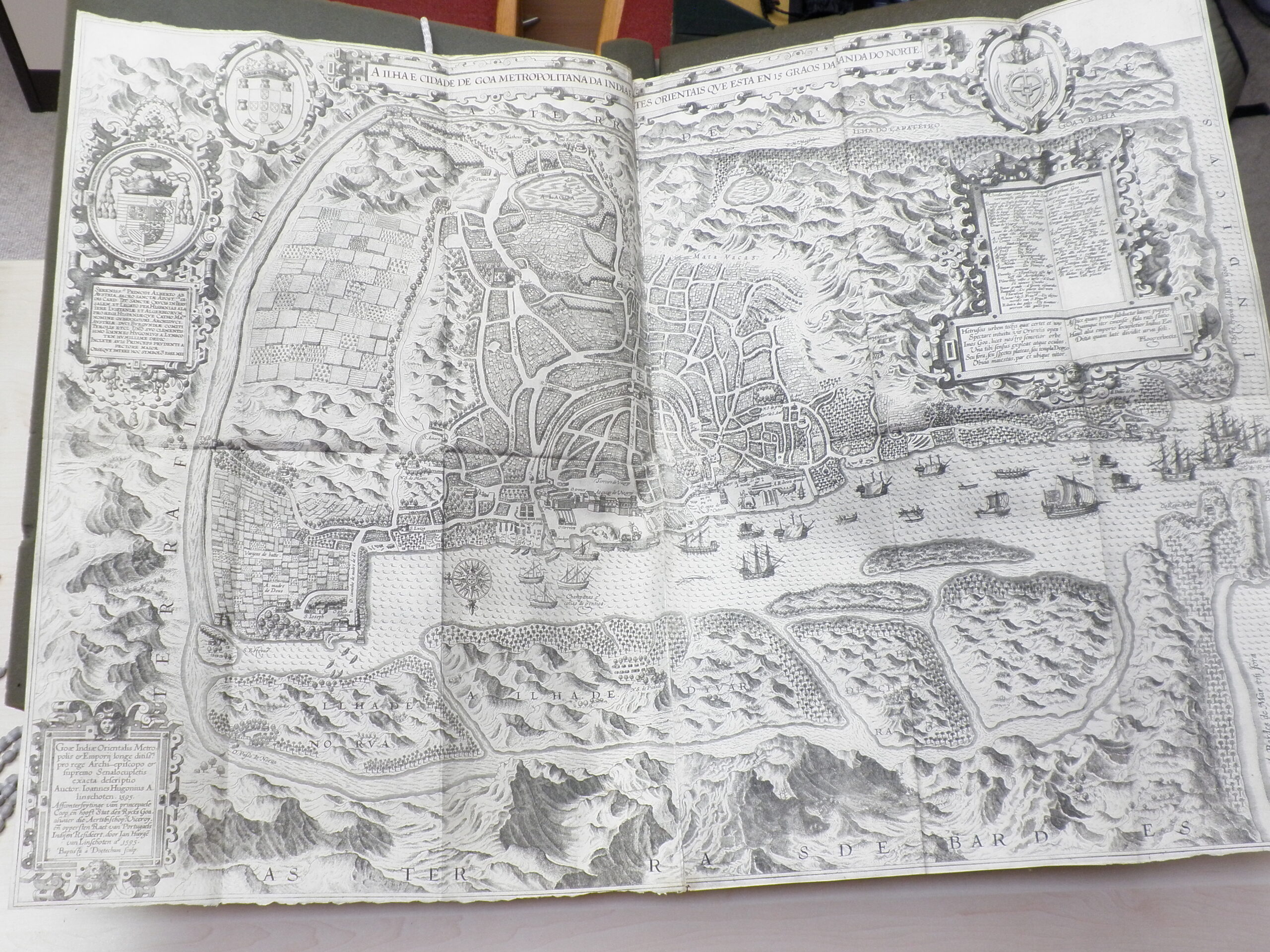

Navigatio ac itinerarium Iohannis Hugonis Linscotani in Orientalem sive Lusitanorum Indiam…

Amstelreodami : Veneunt apud Iohannem Walschaert, 1614.

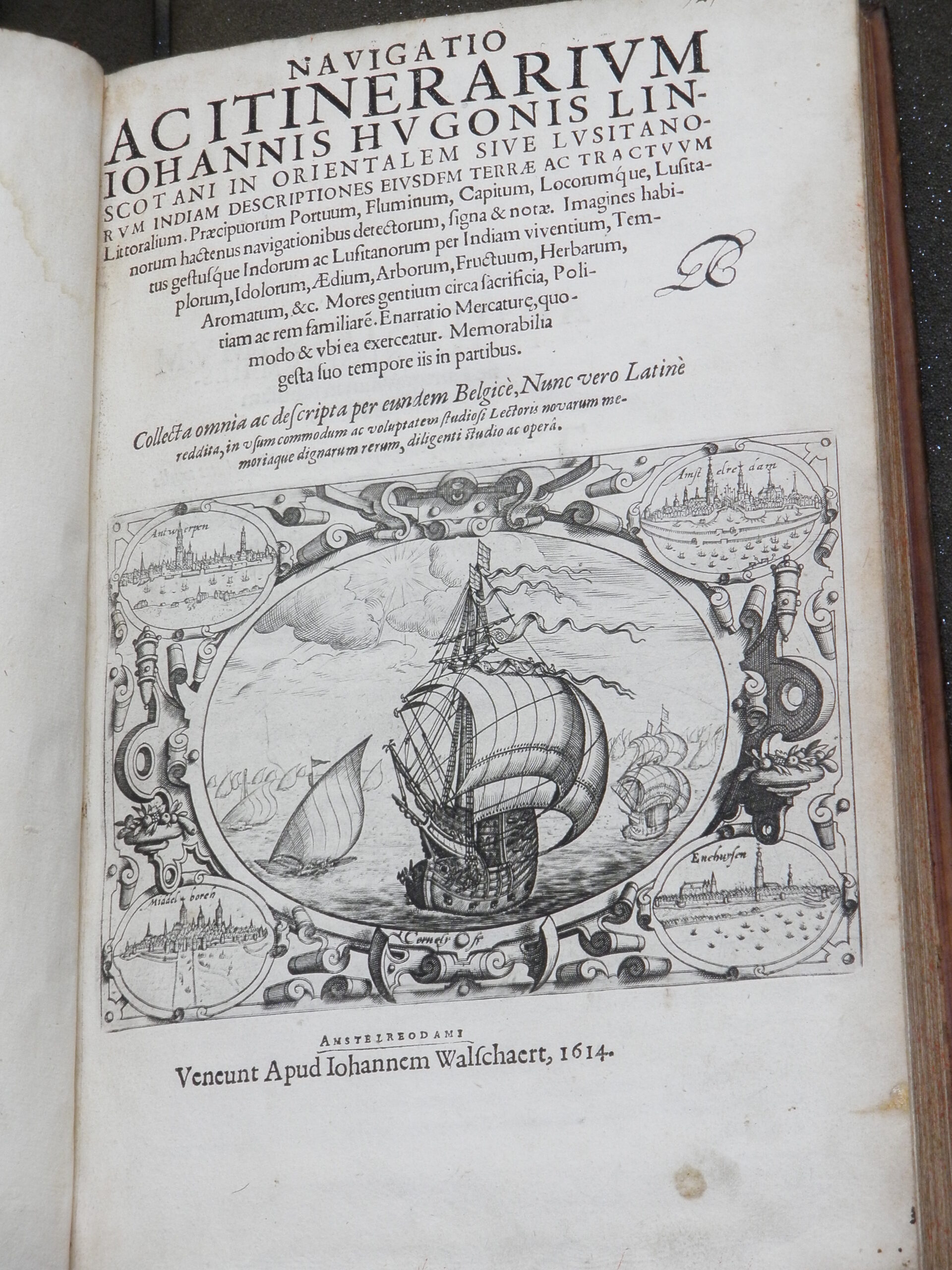

As we hit August and thoughts turn towards vacations, Worcester librarians (who might otherwise spend the month among dusty stacks) are fortunate to have atlases to turn to where one might dream of distant lands. One folio volume, bound in calf, is a 1614 printing of the 1599 Latin translation of Jan Huygen van Linschoten’s Discours of Voyages into ye Easte and West Indies (originally published in Dutch as Itinerario, voyage ofte schipvaert… naer Oost ofte Portugaels Indien by Cornelis Claesz in Amsterdam in 1596). It contains 36 plates and plans, together with six large maps. The text, be it in Dutch, Latin, English, French or German – such was its importance, it was frequently translated in the first decade after its original publication (see Tiele’s Mémoire Bibliographique, pages 83-103) – revealed to northwest Europe trade-routes to southeast Asia that had previously only been exploited by Portugal and Spain (see Durand and Curtis, Maps of Malaya and Borneo, page 40). The Itinerario also ‘contains all kinds of relatively accurate information about the Asian maritime trade and about the daily life of Portuguese and Indians in Goa’ (van den Boogaart in his Foreword to Jan Huygen van Linschoten and the moral map of Asia, page 2).

Jan Huygen van Linschoten (1562/3-1611), Dutch traveller and writer, was born in Haarlem in 1562/3. Aged around 14, he left Holland for Spain, before travelling to Goa in 1583, where he spent five years in the employ of the Portuguese Archbishop of Goa, Vincente de Fonseca. Linschoten used his time in Goa to take note of its customs, peoples, and natural products, notes which he wrote up in his Itinerario on his return to Holland in 1592. Linschoten’s descriptions of daily life in sixteenth-century Goa are considered to be still ‘of great historical value’ (Koeman, ‘Jan Huygen van Linschoten’, page 32), and are supplemented by a series of engravings made after Linschoten’s own drawings of daily life in Goa.

Picture of the principal trading post and capital of the Viceroyalty of Goa, residence of the Archbishop, Viceroy, and Supreme Council of Portuguese India. After a drawing by Linschoten; engraved by P. Hoogerbeets.

A clear record of the market of Goa, with its shops, wares and daily traders. After drawings by Linschoten; engraved by P. Hoogerbeets.

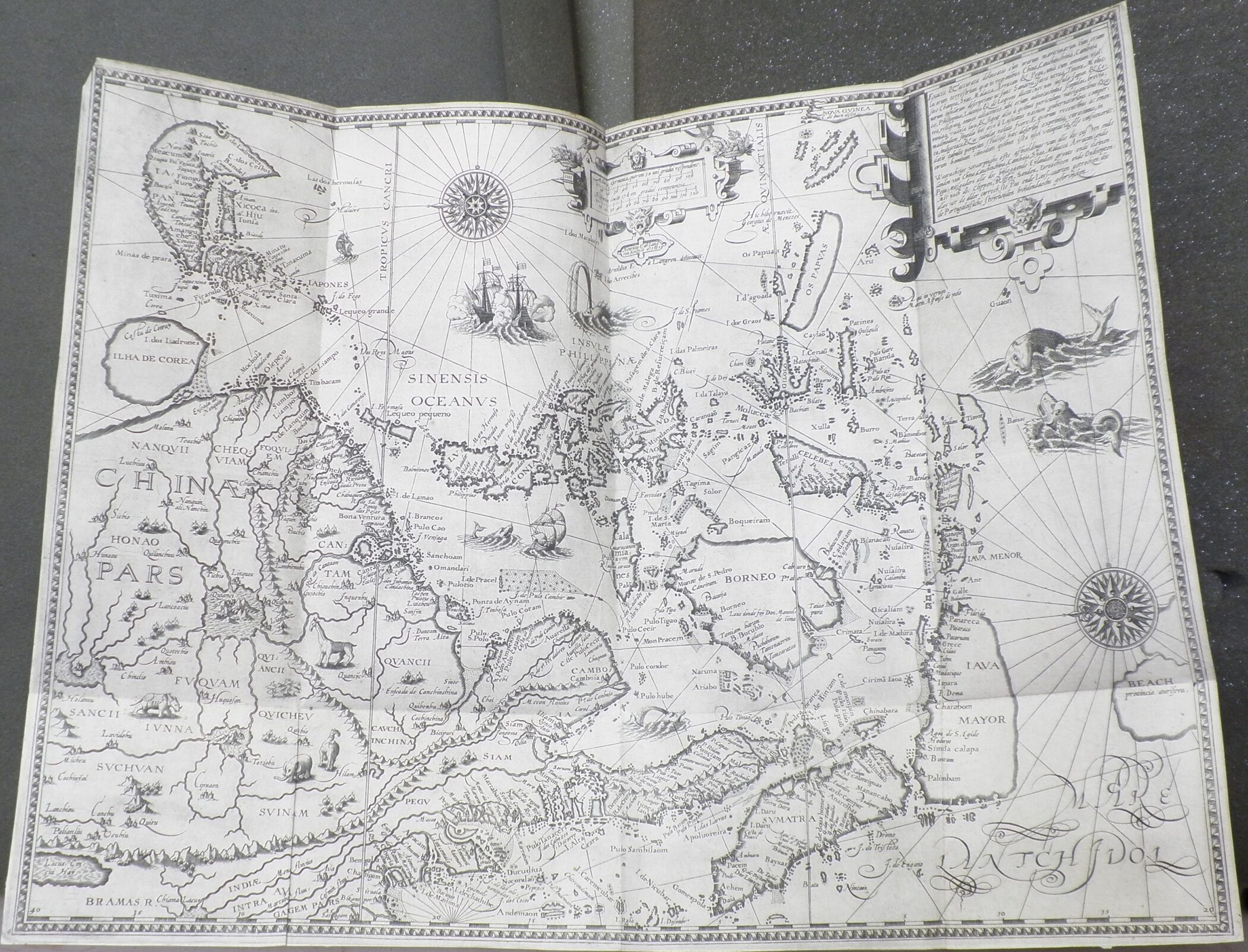

For his contemporaries, however, much of the value of the work undoubtedly lay in its publication of navigational information that had long been unavailable anywhere in Europe outside the Iberian peninsula. The second part of the original Dutch work, the Reys-Gheschifte, contains a collection of the sea routes translated from the manuscripts of Spanish and Portuguese pilots (see Tiele in his Introduction to Burnell and Tiele (eds.), The voyage of John Huyghen van Linschoten to the East Indies, page xxx). These sailing instructions, which included information on currents, islands and sandbanks, were of great use to the ships of the Dutch East India Company (founded in 1602) which brought to an end the sixteenth-century Portuguese monopoly on trade with the East Indies. Important too was Linschoten’s advice on Java, which the Dutch made their headquarters in the region: “men might very well traffique without any impeachment, for that the Portingales come not thether, because great numbers of Java come themselves unto Malacca to sell their wares” (in the words of the 1598 English translation – see volume 1, page 112 of Burnell and Tiele (eds.), The voyage of John Huyghen van Linschoten to the East Indies).

The true depiction or illustration of all the coasts and lands of China, Cochin China, Cambodia, Siam, Malacca, Arracan and Pegu, likewise of all the adjacent islands, large and small, together with the cliffs, riffs, sands, dry parts and shallows; all taken from the most accurate maps in use by the Portuguese pilots today. Drawn by Arnoldus van Langren; engraved by Henricus van Langren.

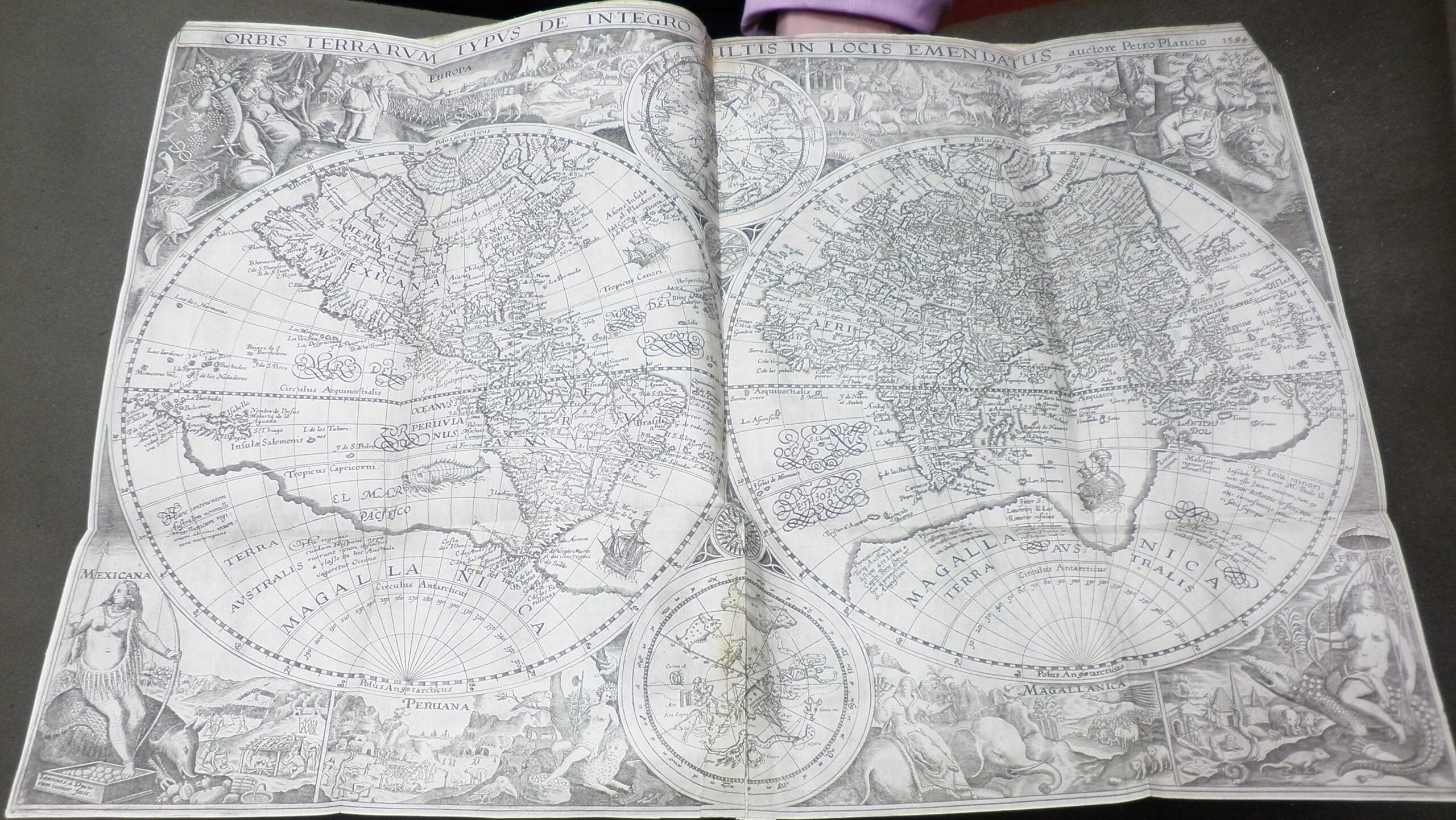

The activities of the Dutch East India Company, which established its own cartographic department, meant that ‘the Netherlands became the home of Europe’s most brilliant cartographers’ in the early seventeenth century (Allen, The atlas of atlases, page 56). This built on the fact that by the 1590s ‘the cities in northern Holland were centres of maritime cartography’ (van den Boogaart, ‘Foreword’, page 18). One of the great early cartographers was Petrus Plancius, whose map of the world features at the start of our volume, there engraved by Henricus van Langren. Plancius used Mercator’s projection, which spaced the lines of latitude further apart as they move away from the Equator, to produce a more accurate map, allowing a spherical earth to be plotted on a flat piece of paper (see Brotton, Great Maps, page 122).

Map of the World

by Petrus Plancius; engraved by Henricus van Langren.

Mark Bainbridge, Librarian

Bibliography

- Allen, P., The atlas of atlases (London, 1992)

- Brotton, J., Great Maps (London, 2014)

- Burnell, A. C., and P. A. Tiele (eds.), The voyage of John Huyghen van Linschoten to the East Indies. From the old English translation of 1598 [by W. Phillip]: the first book, containing his description of the East (London, 1885)

- Durand, F. and R. Curtis, Maps of Malaya and Borneo: discovery, statehood and progress: the collections of H.R.H. Sultan Sharafuddin Idris Shah and Dato’ Richard Curtis (Kuala Lumpur, 2013)

- Koeman, C., ‘Jan Huygen van Linschoten’, in Revista da Universidade de Coimbra 32 (1985), pages 27-47

- Linschoten, J. H. van, and E. van den Boogaart, Jan Huygen van Linschoten and the moral map of Asia (London, 1999)

- Tiele, P. A., Mémoire Bibliographique sur les journaux des navigateurs néerlandais (Amsterdam, 1867)