‘A sort of delightful terror’

31st October 2016

‘A sort of delightful terror’

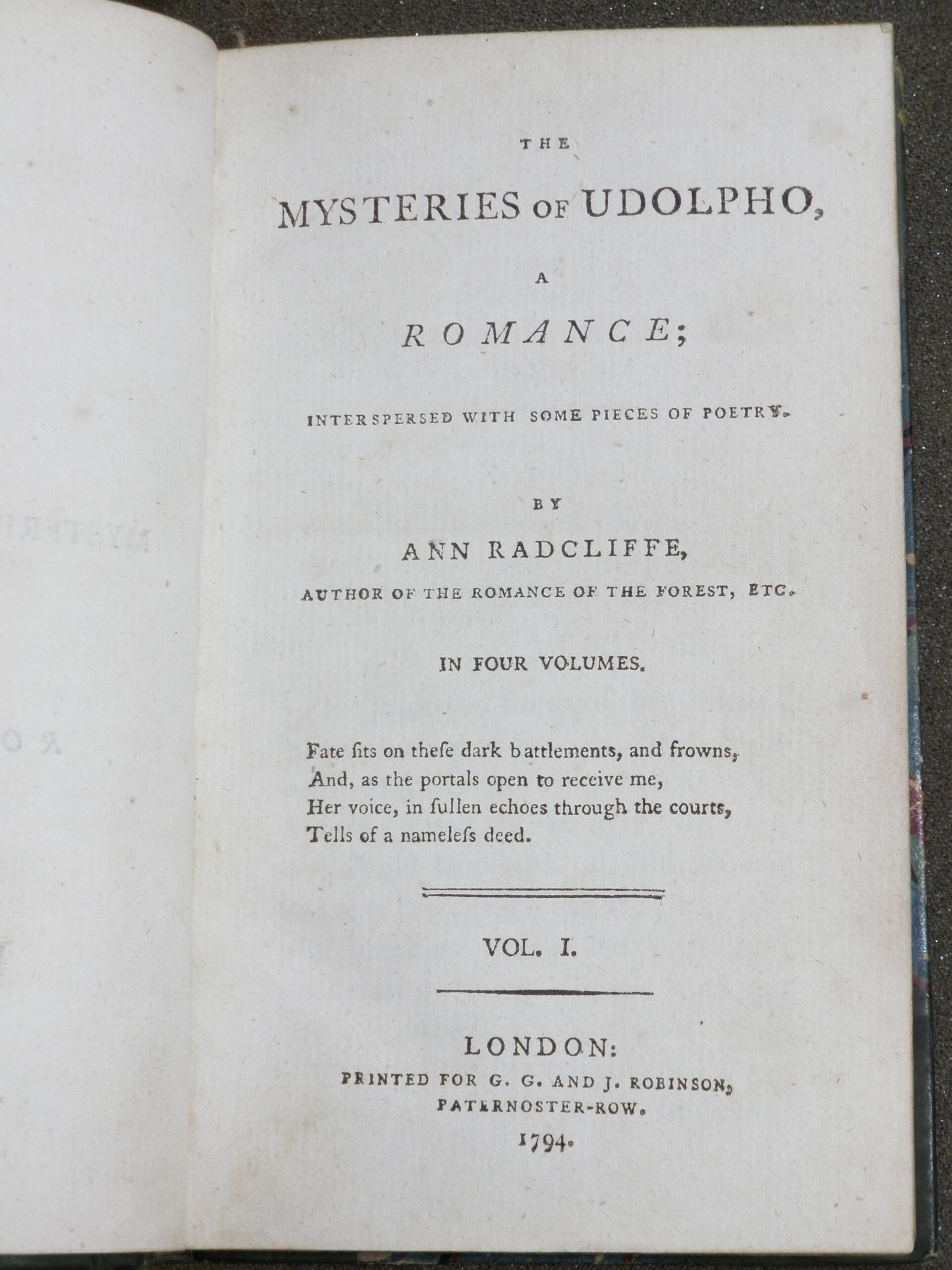

The Mysteries of Udolpho, A Romance; Interspersed with Some Pieces of Poetry, by Ann Radcliffe

In Four Volumes, London: Printed for G.G. and J. Robinson, Paternoster-Row. 1794

In this month of Halloween, we turn to some items in the library’s collections that seek to entertain, thrill, and even terrify us: early gothic literature.

The East Syde of the Bass (published 1695)

Scholars who write on gothic literature are quick to point out that the term ‘gothic’, as applied to literature of this era, is in itself problematic. To begin with, the term is anachronistic and was rarely used before 1920 – contemporaries were more inclined to describe gothic novels as ‘romances’ (Groom, The Gothic, p. 76; Clery, ‘The genesis of Gothic fiction’, p. 22). Both terms were used for the same purpose though: as an allusion to the medieval, or at least, to the medieval as imagined at the time. Contemporaries also often referred to gothic novels as ‘terrorist novels’, referring to the power of such works to inspire terror in their readers (Miles, ‘The 1790s, p. 43). Another problem with ‘gothic literature’ is that it is a very broad church; even when only applied to works produced from c.1780-1820, as we will do here, ‘gothic’ is used to describe everything from the gentle mysteries of Ann Radcliffe to the horror stories of Matthew Lewis.

Nonetheless, there are a number of features that are considered characteristic of gothic fiction, which draw these works together. In her introduction to The Mysteries of Udolpho, Castle, perhaps partly in jest, offers one definition of the ‘gothic’ as ‘a decadent late-eighteenth-century taste for things gloomy, macabre, and medieval’ (Castle, ‘Introduction’, p. vii). Groom quotes a ‘recipe’ from an article on ‘Terrorist Novel Writing’ from 1798:

Take—An old castle, half of it ruinous.

A long gallery, with a great many doors, some secret ones.

Three murdered bodies, quite fresh.

As many skeletons, in chests and presses.

An old woman hanging by the neck; with her throat cut.

Assassins and desperadoes ‘quant suff.’

Noise, whispers, and groans, threescore at least.

Mix them together, in the form of three volumes to be taken at any of the watering places, before going to bed. (Groom, The Gothic, p. 78)

Humour aside, gothic novels usually did feature an antiquated setting of some sort (ruined castles or abbeys were popular) which was haunted by secrets from the past – often quite literally in the form of ghosts or monsters (Hogle, ‘Introduction’, pp. 2-3). A young heroine or pair of young lovers was often pitted against a corrupt or lecherous patriarchal figure, such as an aristocratic uncle or a priest, and the plot tended to involve an escape from some form of imprisonment (Cox, ‘English Gothic Theatre’, p. 128). The settings were usually, but not always, continental and vaguely medieval, though geographical and historical accuracy were not essential. Ann Radcliffe, despite the detailed descriptions of scenery in her works, never travelled to any of the places where her novels were set (Dobrée, ‘Introduction’, p. 8).

Dunotter Castle, sold by J. Nutting Engraver and Print seller (published 1710)

Scholars have posited a number of explanations for the popularity of the gothic in Britain at this particular point in history. Gothic literature is frequently tied to the French Revolution, though the exact nature of the relationship is heavily debated (for more see Groom, The Gothic, chapter 8; Miles, ‘The 1790s’; and Cox, ‘English Gothic Theatre’). Others see the interest in mysteries and the supernatural as a reaction to the rationality of the Enlightenment, as well as to the predominance of realistic novels following the success of Richardson and Fielding (Castle, ‘Introduction’, pp. xxi-xxii; Clery, ‘The Genesis’, p. 33). Edmund Burke’s work, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757), is frequently cited when discussing the popularity of gothic literature at this time. Burke’s theories shed some light not only on ideologies of the time which contributed to the popularity of the gothic, but perhaps as well on the enduring popularity of mystery and terror to this day. Burke’s treatise seeks to compare the opposite causes and effects of the beautiful and the sublime – while beauty is linked to pleasure, the sublime is linked to terror, astonishment, and self-preservation (Clery and Miles, Gothic Documents, p. 112). Burke argues that just as muscles need to be exercised by painful, manual labour to stay in shape, so too the mind needs to be stimulated by terror to stay active (Clery, ‘The Genesis’, p. 28; also excerpted in Clery and Miles, Gothic Documents, pp. 120-121). Writes Burke:

‘…if the pain and terror are so modified as not to be actually noxious… as these emotions clear the parts, whether fine, or gross, of a dangerous and troublesome incumbrance, they are capable of producing delight; not pleasure, but a sort of delightful terror, a sort of tranquillity tinged with terror; which as it belongs to self-preservation is one of the strongest of all the passions.’ (excerpted in Clery and Miles, Gothic Documents, p. 121)

Despite its popularity at the time, Gothic literature is not a prominent feature of the library’s special collections. Gothic fiction was seen as sensationalist entertainment and would not have been considered suitable for an academic library. Only in the last thirty or forty years have early gothic novels become a topic of academic study. So it is somewhat surprising to find that the library owns a first edition of Ann Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho.

The Mysteries of Udolpho was published in 1794 in four volumes by G.G. and J. Robinson. Udolpho features many of the standard elements of a gothic novel – the young heroine falls under the control of a scheming Italian aristocrat who imprisons her in his gloomy castle and thwarts her romance with the hero in order to achieve his own ends. Dark secrets, dramatic landscapes, and an apparent ghost all make an appearance. Udolpho was an immense success. A second edition was produced the same year, and further editions in 1795, 1799, 1803, and 1806 (Castle, ‘Introduction’, p. xxvii). The novel continued to be popular and reprinted well into the nineteenth-century (Castle, ‘Introduction’, p. xx). It was also translated into French, German, Italian and Russian (Castle, ‘Introduction’, p. xxviii). At a time when the average payment for copyright was £80, Udolpho commanded the astonishing sum of £500 from Radcliffe’s publishers (Miles, ‘Radcliffe, Ann’).

Ann Radcliffe dominated and defined the genre of gothic romance in the 1790s yet her works were unusual in their rational explanations of the supernatural. Where other gothic novels often featured genuine hauntings, Radcliffe’s ghosts were always explained away by the end of the novel. Whether readers preferred this is hard to say. Sir Walter Scott (a big fan of Radcliffe’s) imagined that most readers felt ‘disappointment and displeasure’ when the mysteries of the novel were explained (Castle, ‘Introduction’, pp. xxii-xxiii). But some modern scholars, such as Clery, have argued that the explained supernatural allowed British readers to reconcile ‘Protestant incredulity and the taste for ghostly terror’ (‘The Genesis’, p.27).

Udolpho is not the only gothic work lurking in the stacks here. As well as a second edition of Radcliffe’s The Romance of the Forest, a handful of gothic plays can be found in bound collections of British theatre. Gothic drama flourished at the same time as gothic literature and featured similar tropes (Cox, ‘English Gothic Drama’, p. 128). Larger theatres and improving technologies made possible exciting light, stage, and musical effects, which could be put to good use creating thrills and chills (Cox, ‘English Gothic Drama’, p.127). Worcester is better known for its substantial collection of printed plays from the early modern era, but we also have a few works by the gothic novelists and playwrights Sophia Lee and Harriet Lee. The Lee sisters were the daughters of actors and turned to writing to save themselves from destitution (Alliston, ‘Lee, Sophia’). Their works have been described as the equivalent of modern day ‘thrillers’ – exciting rather than terrifying (Dobrée, ‘Introduction’, p. vii). The library has early printings of The Chapter of Accidents (1780) and Almeyda; Queen of Grenada (1796) by Sophia Lee and The Mysterious Marriage, or the Heirship of Roselva (1798) by Harriet Lee.

How did these works end up here? The plays are most easily explained. Almedya; Queen of Grenada and The Mysterious Marriage are bound together in a volume which belonged to Henry Allison Pottinger, Librarian of Worcester from 1884-1911. Pottinger was a voracious and eclectic collector and amassed a large collection of nineteenth-century pamphlets on all subjects, which is now a part of the library. The Chapter of Accidents is bound with a miscellaneous collection of pamphlets which lacks Pottinger’s stamp, however it would be safe to assume it was one of his acquisitions as well. The presence of Udolpho and The Romance of the Forest shall remain a mystery however. The volumes bear no ownership inscriptions and cannot be traced to a particular librarian in Worcester’s past. What is most likely is that they arrived as part of a larger donation or acquisition at a time when their age and fine bindings were enough to secure them a place on the library shelves, where they can continue to ‘delightfully terrify’ our readers for years to come.

Renée Prud’Homme, Assistant Librarian

Bibliography

- Alliston, April, ‘Lee, Harriet (1757/8–1851)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/16287, accessed 28 Oct 2016]

- Alliston, April, ‘Lee, Sophia Priscilla (bap. 1750, d. 1824)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/16311, accessed 28 Oct 2016]

- Clery, E.J., ‘The genesis of “Gothic Fiction”’ in Jerrold E. Hogle (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Gothic Fiction (Cambridge 2002)

- Clery, E.J. and Miles, Robert (eds.), Gothic Documents: a Sourcebook 1700-1820 (Manchester 2000)

- Cox, Jeffrey N., ‘English Gothic Theatre’ in Jerrold E. Hogle (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Gothic Fiction (Cambridge 2002)

- Groom, Nick, The Gothic: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford 2012)

- Hogle, Jerrold E., ‘Introduction: the Gothic in Western Culture’ in Jerrold E. Hogle (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Gothic Fiction (Cambridge 2002)

- Miles, Robert, ‘Radcliffe, Ann (1764–1823)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Oct 2005 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/22974, accessed 28 Oct 2016]

- Miles, Robert, ‘The 1790s: the effulgence of Gothic’ in Jerrold E. Hogle (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Gothic Fiction (Cambridge 2002)

- Radcliffe, Ann, The Mysteries of Udolpho, edited with an introduction by Bonamy Dobrée (Oxford 1980)

- Radcliffe, Ann, The Mysteries of Udolpho, with an introduction by Terry Castle (Oxford 1998)