‘Legislation for the unrepresented is tyranny’

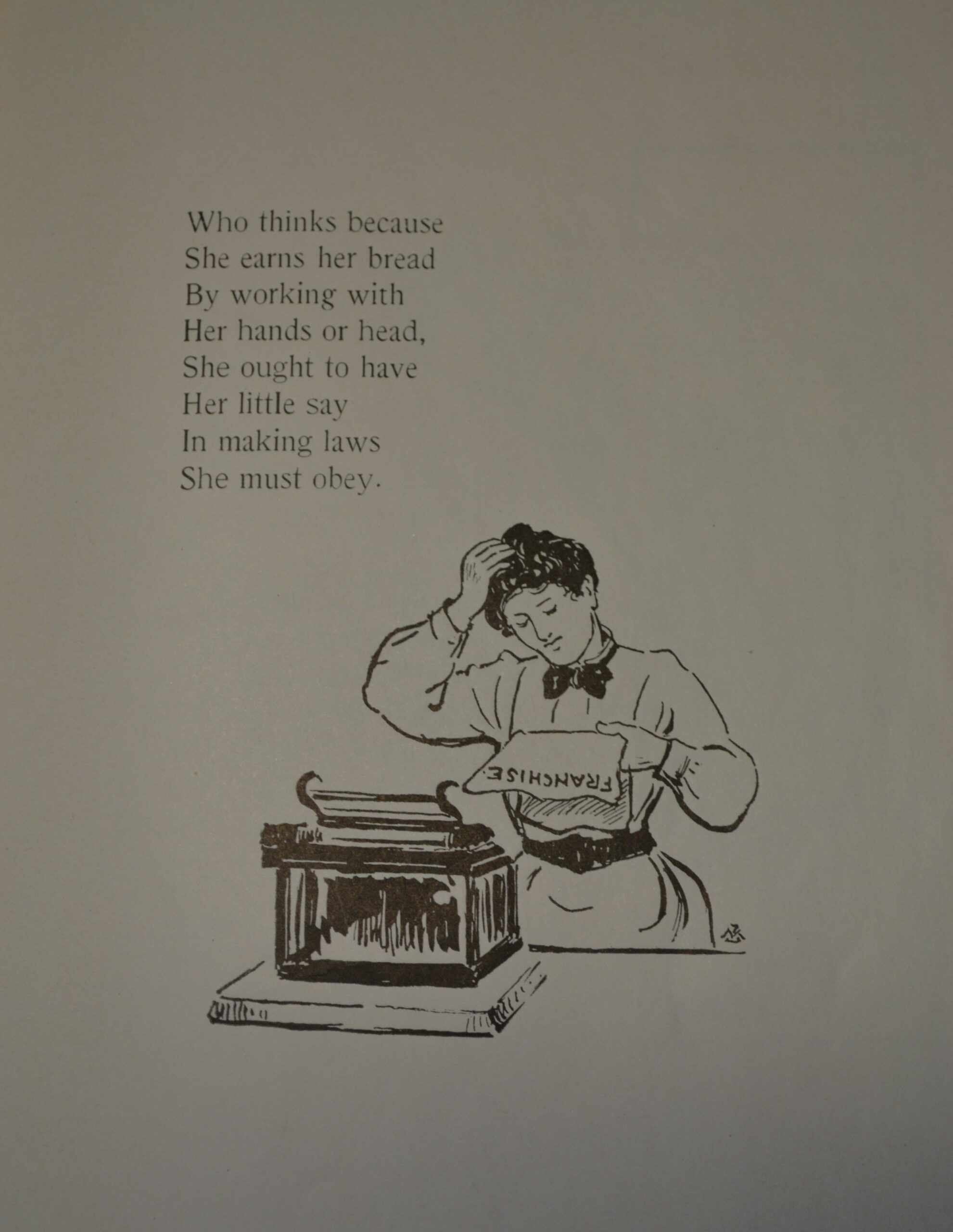

28th February 2018

‘Legislation for the unrepresented is tyranny’

Pamphlets Relating to Women’s Suffrage, c. 1870 – 1918

‘It is not merely that they pay rates and taxes and ought to have a voice as to their distribution and expenditure, the far broader human truth remains, legislation for the unrepresented is tyranny. Women suffer as women, as wives, and as mothers from evil laws, and ask to have a direct voice in so reforming these laws that they shall protect, not the selfish interest of either sex or of any class, but the larger, deeper, more vital interests of humanity itself, of justice for to-day, of hope, and progress for the future.’ – Elizabeth C. Wolstenholme Elmy, The emancipation of women (1888)

This month, in honour of the 100th anniversary of the Representation of the People Act 1918 on February 6th, which first extended the parliamentary franchise to some women in Britain, we are delving into both our nineteenth-century pamphlet collection and the College Archives to look at some of the ephemera published in the course of the campaign for women’s suffrage.

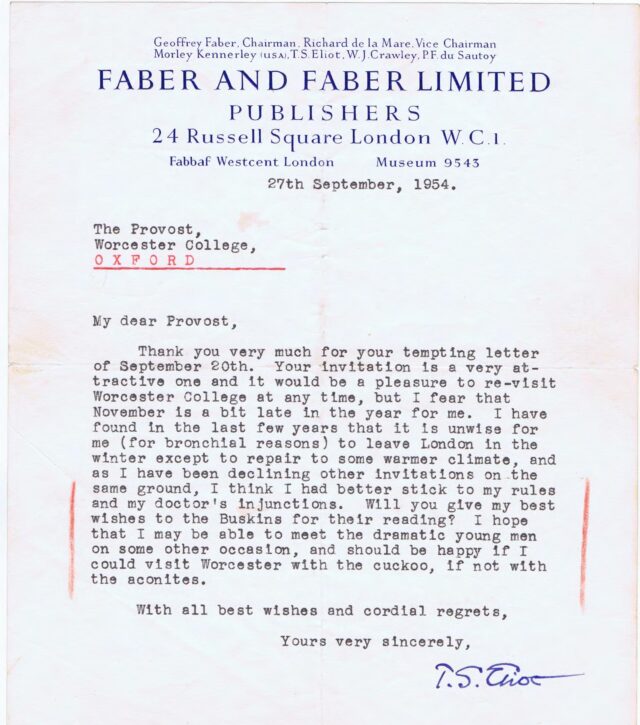

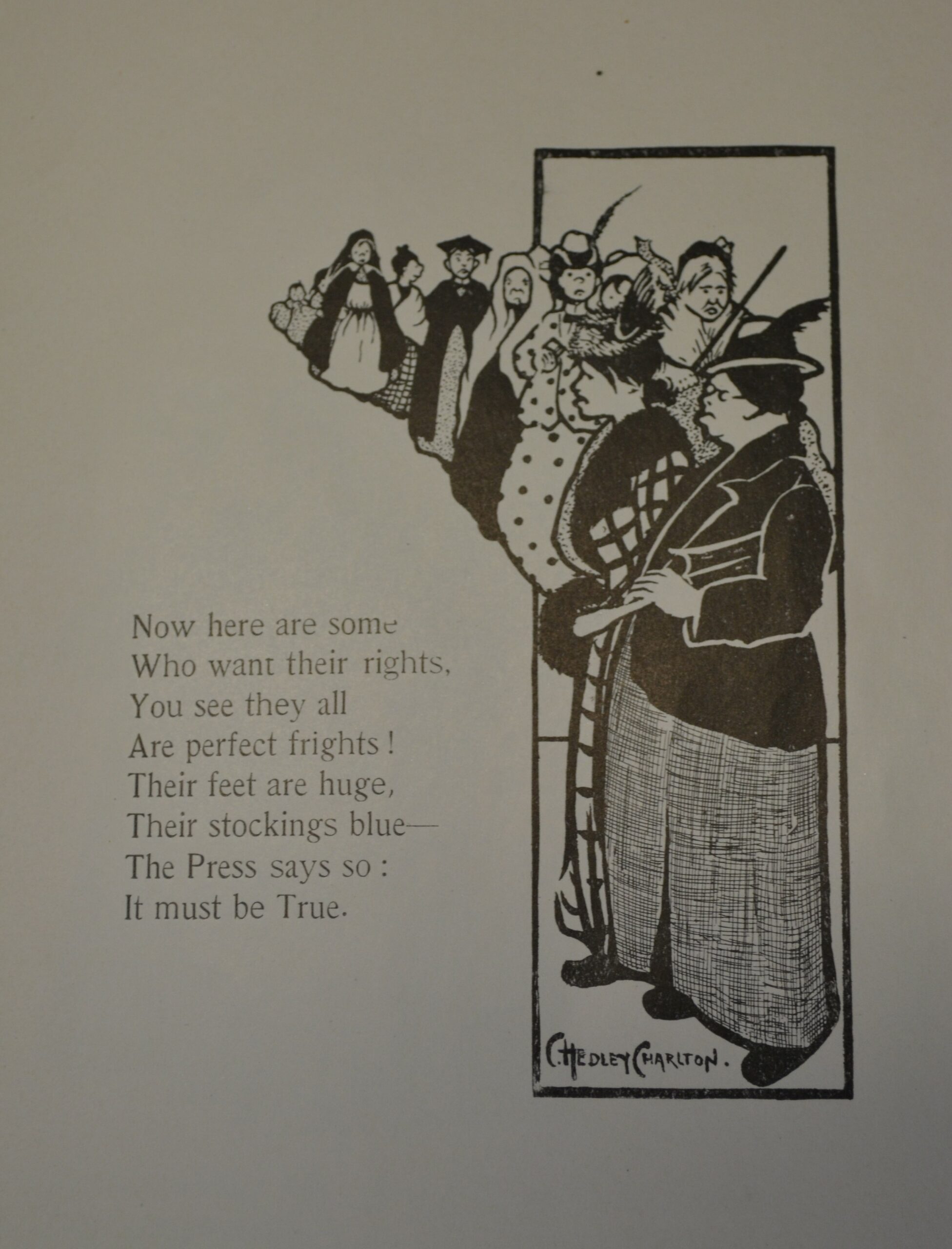

Image from the satirical pamphlet Beware! A Warning – to Suffragists, by Cicely Hamilton (1909).

The organised campaign for women’s suffrage began in 1866 with the ‘Ladies Petition’ to parliament, which requested that the vote be granted to all householders regardless of sex (Wingerden, The Women’s Suffrage Movement in Britain, p. 2). John Stuart Mill then proposed an amendment to the 1867 Representation of the People Act to enfranchise women. The amendment was defeated, but the organised movement for women’s suffrage was born (Wingerden, Women’s Suffrage Movement, pp. 11-15).

Under various organisations and titles, suffragists continued to campaign for voting rights, as well as other women’s rights, for the next 60 years. Progress for suffrage was slow – the parliamentary franchise would remain out of reach until 1918 and was only granted on equal terms with men in 1928 – but the movement achieved many other legislative successes in the areas of maternal rights, property rights, and local voting rights (Wingerden, Women’s Suffrage Movement, pp. 37-39).

Image from the satirical pamphlet Beware! A Warning – to Suffragists, by Cicely Hamilton (1909).

Our pamphlet collection contains a number of publications from the 1870s – 1890s on the topic of women’s suffrage, both in favour and in opposition, and showcasing the diversity of the movement. There are reports of meetings held by women’s suffrage organisations, reprints of letters published in the press, petitions, and more substantial publications on the topic. As with most of our pamphlet collection, these probably came to the Library through the eclectic collecting habits of Henry Allison Pottinger (Librarian 1884-1911) – indeed a number of them still bear his stamp.

The campaign for women’s suffrage was not monolithic and this can be seen in the pamphlets we hold. The pro-suffrage pamphlets vary from authors seeking only enfranchisement for unmarried or widowed property holders, to those seeking full legal and political equality with men (though what this entailed changed over the course of the century as the male franchise expanded). In particular, there was a substantial division in the movement over the vote for married women, which resulted in a number of prominent activists, including Emmeline Pankhurst, Harriet McIlquham, and Elizabeth Wolstenholme Elmy, breaking off to form a more radical organisation, the Women’s Franchise League (Wingerden, Women’s Suffrage Movement, p. 61). One of our most interesting pamphlets is the Report of Proceedings at the Inaugural Meeting: London, July 25th, 1889 of the Women’s Franchise League, in which Mrs McIlquham lays out the case for insisting that married women be included in any extension of the franchise to women. Throughout the text, there are annotations which appear to be roughly contemporary with the text. Next to a reference to a noted anti-suffragist, our annotator has written ‘now converted’, and the address on the back of the pamphlet has been updated, which suggests that the annotator was associated with the movement or acquainted with those involved. The annotator has also underlined and commented on key passages in the text.

We also hold a number of pamphlets written by those who opposed women’s suffrage, which are also varied in their arguments and approach. For the modern reader, it is somewhat astonishing to read of the apocalyptic consequences some opponents foresaw as the result of female enfranchisement. One pamphlet writer even argued that enfranchising women would eventually lead to the destruction of free institutions and the rule of law. Writing in 1875, Goldwin Smith begins by stating that ‘It may not be easy to say beforehand exactly what course the demolition of free institutions by female suffrage would take,’ but he goes on to provide a number of ideas (Smith, Female Suffrage, p. 19).

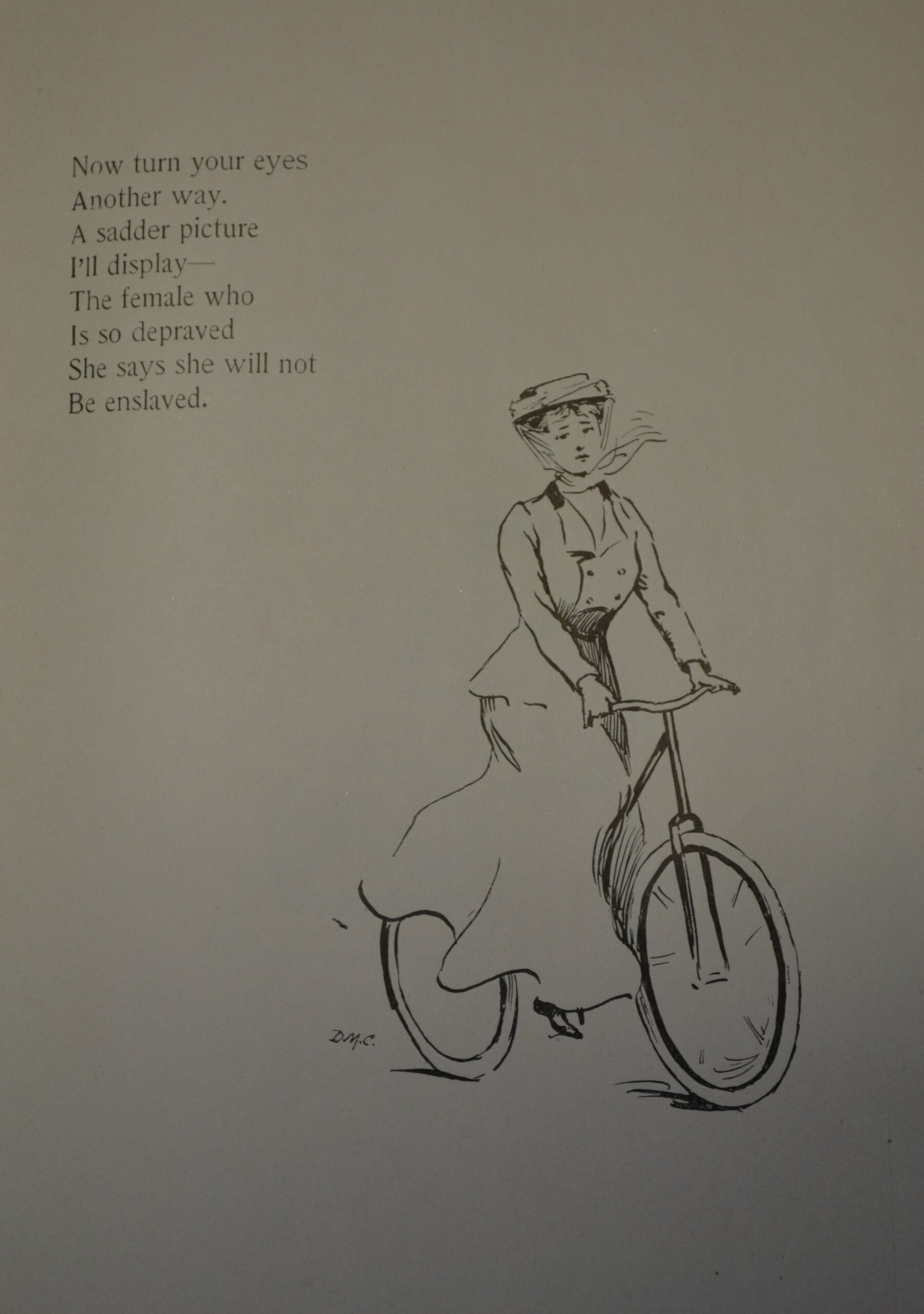

An image by C. Hedley Charlton from Beware! A Warning – to Suffragists, by Cicely Hamilton (1909).

Similar dire warnings are satirized in a pamphlet from the College Archives: Beware! A warning – to Suffragists by Cicely Hamilton (1909) (extracts feature in the illustrations accompanying this piece). While assertions such as Smith’s seem almost comical now, the sway that this concept of female political incapacity still held over society, and parliament in particular, must have caused suffragists no end of frustration. Some sense of this can be felt in Mona Caird’s letter to the Manchester Guardian in 1891, which was reprinted as a pamphlet entitled ‘The Position of Women’. She writes of the man who believes women have no business in political life:

‘“Woman,” he says from this vantage ground – “woman was not made to meddle in politics.” How he knows this one vaguely wonders. One also wonders if he has authentic information that man, on the other hand, was fashioned for that august purpose, and if so, why he has so frequently disappointed his creator.’

Many of the pro-suffrage pamphlets are written as replies to the arguments put forward by anti-suffragists and indeed we have ephemera from both sides of a war of words and petitions which played out in the press in the summer of 1889. In June 1889, Mrs Humphrey Ward appealed in Nineteenth Century magazine for signatures to protest against women’s suffrage (Wingerden, Women’s Suffrage Movement, p. 61). The result was a nearly 30-page list of women’s signatures to a statement arguing that female enfranchisement would be ‘distasteful to the great majority of the women of the country – unnecessary – and mischievous to both themselves and to the State’ (Signatures to the Protest Against Female Suffrage, reprinted from the ‘Nineteenth Century’, No. 150, August 1889). Suffragists were quick to reply to Humphrey Ward’s appeal and in July 1889 they published in The Fortnightly Review their own extensive list of signatures in favour of women’s suffrage, as well as an article criticising the arguments of the ladies in opposition (Women’s Suffrage: A Reply, reprinted from ‘The Fortnightly Review’, July 1889).

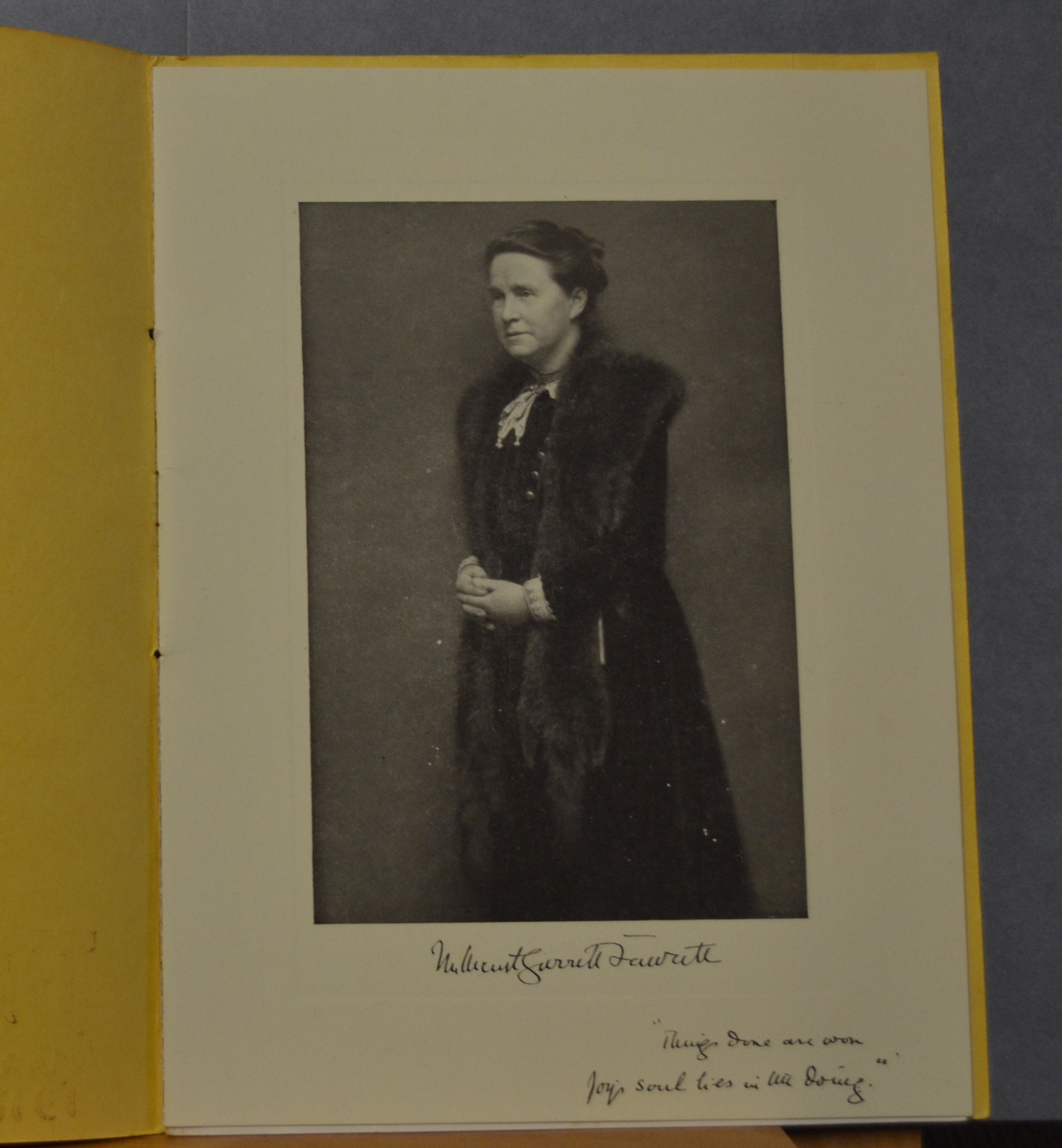

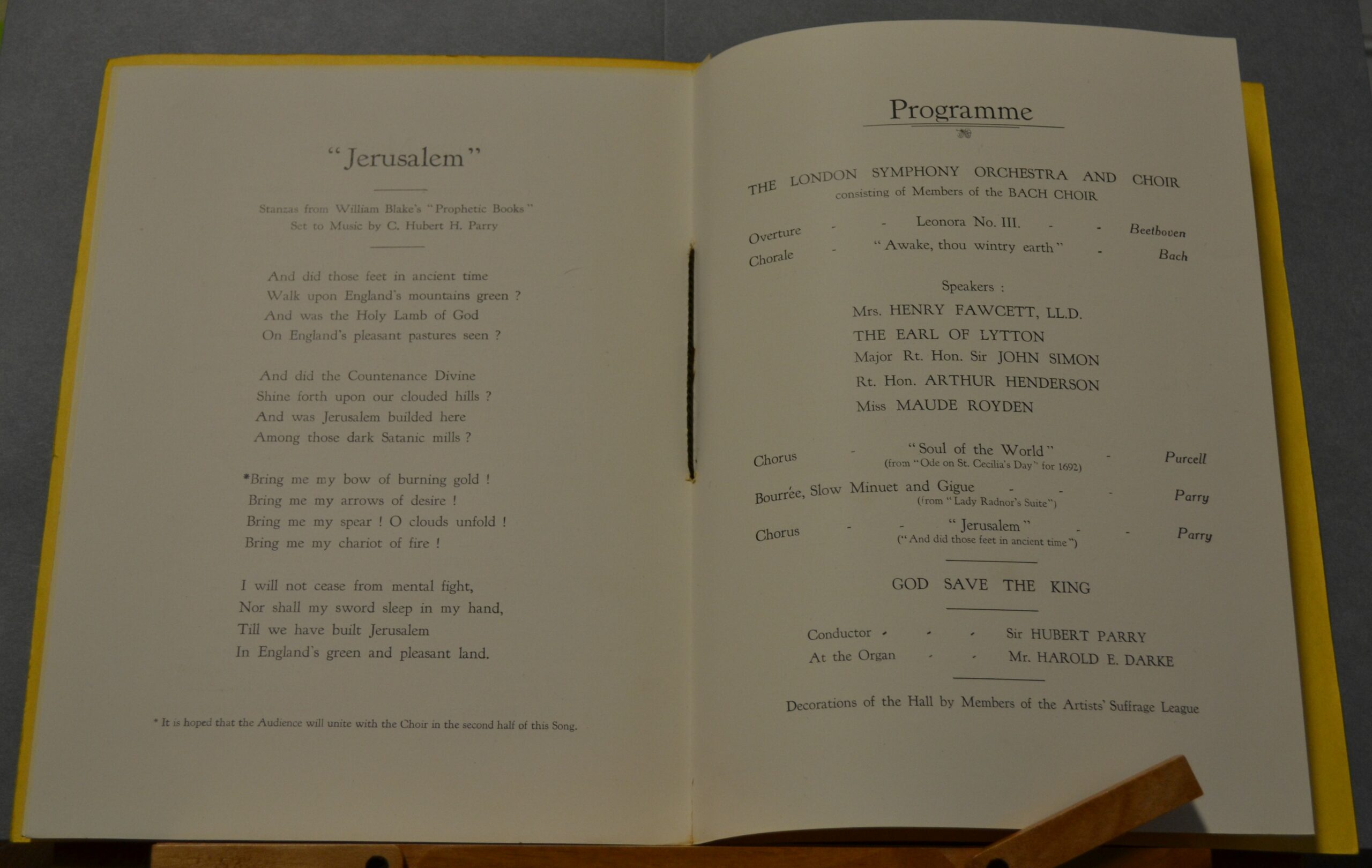

Though the writers of many of our late nineteenth-century pamphlets seemed certain that success was just around the corner, from hindsight we can see that it would take the massive social upheaval caused by the First World War to scuttle the foundation of ‘separate spheres’ which underpinned the resistance to parliamentary enfranchisement for women. But finally in 1918 women over 31 were given the vote and in the archives, as part of the Hadow papers, we hold a programme for a meeting of thanksgiving held 13 March 1918. Millicent Fawcett, President of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), later wrote that they had “held no great meetings in support of Women’s Suffrage during the Great War…But in March 1918 we felt we must have one meeting of thanksgiving for the Parliamentary victory we had gained” (Fawcett, What I Remember, p. 249).

Photograph of Millicent Fawcett reproduced in the meeting programme.

This meeting, at Queen’s Hall in London, comprised a number of speeches and also a programme of music by the London Symphony Orchestra and Choir, conducted by Sir Hubert Parry. During the meeting the audience joined the choir in singing ‘Jerusalem’, which Parry had set to music in March 1916, and it was directly in response to this occasion that Parry assigned the copyright of the song to the NUWSS and it became their official anthem. Copyright of the song was transferred to the Women’s Institute in 1928 after the NUWSS was split into two groups following the extension of the franchise to all women over the age of 18.

Programme of the meeting with lyrics for “Jerusalem”.

The copy of the programme now in the College Archives belonged to Grace Hadow who attended the meeting. As a member of the Cirencester branch of the NUWSS Grace Hadow campaigned for women’s suffrage from 1912 to 1917. Helena Deneke writes in her biography that “such activity earned Grace unpopularity with the local great; at least she felt it did, but she was ardent in the cause and worked for it steadily” (Deneke, Grace Hadow, p. 54). A fervent admirer of Millicent Fawcett, Grace Hadow was opposed to the militancy of the suffragettes but did later admit that they had advanced the cause, although she considered that the real breakthrough had been the changing role of women in the workplace during the First World War. Grace Hadow later became Principal of the Society of Oxford Home Students (now St Anne’s College), but her connection with Worcester College is through her brother, Sir William Henry Hadow (Fellow 1890-1909). Their niece, Enid Hadow, generously donated her collection of Hadow family papers to the Archives between 1966 and 1969.

Grace Hadow and her eldest brother, William Henry Hadow (Fellow of Worcester College 1890-1909)

While Millicent Fawcett considered the enactment of the 1918 Representation of the People Act as the greatest moment in her life, suffragists were highly aware that they had not obtained the equal suffrage rights for which they had been campaigning since the 1860s. Although the front cover of the March 1918 ‘victory’ programme fittingly shows the blazing sunrise of a new dawn for women, the struggle for universal suffrage would not end until 1928.

Emma Goodrum, Archivist and Renée Prud’Homme, Assistant Librarian

Bibliography

- Deneke, Helena, Grace Hadow (London: Oxford University Press, 1946)

- Dibble, Jeremy, C. Hubert H. Parry: his life and music (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992)

- Fawcett, Millicent Garrett, What I Remember (London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1924)

- Smith, Harold L., The British Women’s Suffrage Campaign 1866-1928 (2nd ed. Harlow: Longman, 2007)

- van Wingerden, Sophia A., The Women’s Suffrage Movement in Britain, 1866-1928 (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1999)