By Professor Alastair Small (1960) – an edited version appeared in the College Record 2021.

“Alec”, The Rt. Reverend Andrew Alexander Kenny Graham, was born on 7 August 1929, the only child of two very different parents. His father, Andrew Harrison Graham, was born at Ben Rhydding in Yorkshire, and educated at Hymers College in Kingston upon Hull. He worked all his life for the National Bank of India becoming a director at the head office in London, responsible for investments. He was a strict father who believed in the merits of cold baths. Alec rarely referred to him, though he sometimes spoke of his father’s older brother, Joseph William Graham, an engineer who built railways in India and (during WWI) in Africa to facilitate the movements of allied troops.

His mother, Magdalene, was eighteen years younger than her husband. She was one of three daughters of Alexander S. Kenny (also known as Alec), a New Zealander and an expert in tropical diseases who came from New Zealand to study in the School of Tropical Medicine in London. He was appointed Demonstrator in Anatomy at King’s College London where he published a standard work on The Tissues and Their Structure, but failed to get the chair he wanted and returned to New Zealand to practise as a doctor. He died soon after, in 1901, leaving his widow, Mary Grace Symonds Kenny, with no friends or relatives in New Zealand. She returned to England with her children. When she got there she had no easy means of support, but she was assisted by her sister who had no family of her own, took in lodgers, and managed to get her children well educated in schools which had charitable foundations. Alec knew her well and was very fond of her.

Alec’s parents were married in Bromley, Kent in 1928 and went to live in Highgate where Alec was born. When he reached school age the family moved from Highgate to Tonbridge where he went to Tonbridge prep school – and then to Tonbridge School where he studied modern languages. He went first as a day boy while the war was still on because (according to his mother) if his family “went” they might as well all go together. Tonbridge was in the flight path of German bombers heading for London, and Alec remembered the excitement of watching planes being shot down in the Battle or Britain. His parents had a small air-raid shelter built below the house with access from below the dining table. It was big enough to take his mother and himself.

After the war Alec continued as a boarder at Tonbridge. He enjoyed the change from a rather solitary life at home, and made the first of many long-lasting friendships, notably with George Young whom he came to regard as a brother. They shared the same political and social views, and the same love of railway trains; and they exchanged letters weekly all their lives.

After leaving school he spent two years on national service in REME, and presumed that he was enlisted in the engineers after revealing that his uncle had been a railway engineer in WW I. He was attached to a unit at Longmoor in Hampshire monitoring movements of men and equipment on trains at Liss station. This was a relatively light-weight task made easier by the complaisance of Mr. Churcher, the civilian stores manager in charge.

After military service Alec went to St John’s College, Oxford with a scholarship to read French and German. He got a 2nd class degree in Modern Languages, and then changed direction, enrolling for the Diploma in Theology at St John’s. For his special subject he studied the theology of Dietrich Bonhoeffer which allowed him to make use of his German language skills. He was supervised by Geoffrey Lampe, whom he admired greatly (and who went on to become Cadbury Professor of Theology in the University of Birmingham, then Ely Professor of Divinity and (from 1970) Regius Professor of Divinity at Cambridge). He proved to have great aptitude for theology and got the diploma with distinction. During his student career he was attracted to the High Church ceremonial of Pusey House, and although he later gave up on some of its liturgical practices, he retained a love for richness of decoration in church buildings, including most obviously Burges’s highly ornate interior of the Worcester chapel.

After Oxford he went to Ely Theological College for two years to train for the priesthood, and was ordained in Chichester Cathedral on 17 May 1956 by the bishop, George Bell. His mother died two weeks after his ordination, at age 57. Alec remembered wistfully that she was unable to attend his ordination, but knew about it.

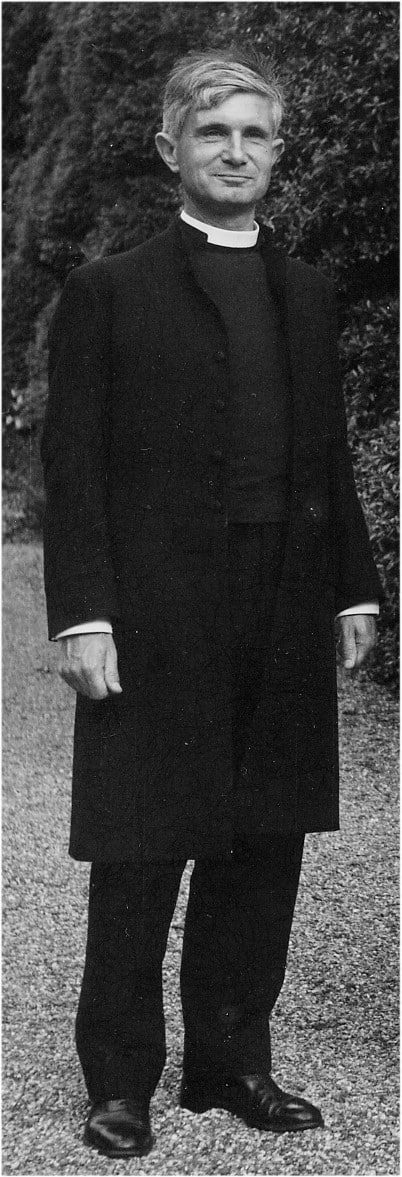

He served as a Curate at Hove for two years, under the rector, Vernon Lippiett, a classics scholar with three first class degrees from Cambridge who was precise in his use of the Greek New Testament, and authoritative – an excellent supervisor of Alec’s curacy. He then applied, at Lampe’s suggestion, for the position of college chaplain and tutor in theology at Worcester College. He was interviewed and was told that the college would like to appoint him for three years (from 1958) as chaplain on a trial basis, and that after three years he might be considered for a fellowship. In fact he was made a full tutorial fellow after two years. James Campbell (the tutorial fellow in history at the time) told Dick Smethurst another side of this story. The college had short-listed a large number of candidates for the position in 1958, but did not think any of them was suitable. The Provost, J.C. Masterman, mentioned this to his friend, the President of St John’s, who suggested that they should interview Alec.

At Worcester he combined the roles of tutor in theology and College chaplain with marked success in both. As chaplain he related well to a wide range of students, not all of whom would have described themselves as Christian. He sent all freshmen shortly after they arrived an invitation to tea or sherry in small groups in his rooms, with a note saying “No answer if this suits you”. Tony Murray (1959) records that when he and several other students were invited for tea Alec said “Worcester men are usually considered to be nice but thick” – spoken very earnestly, and leaving them to decide whether it was a joke. He adds that he was struck by Alec’s tolerance. Alec noted his absence from all chapel services until the time came for him to carry out his duty of reading the lesson, but assured him that there would be no hard feelings if he ducked out – which he did not because, although he could not be described as Christian in any theological sense, he could not bear to pass up the chance to read from the glorious Authorized Version in the acoustics of the chapel.

The students generally found that Alec was an undogmatic chaplain who was a good listener and a wise counsellor. He had various gambits to put them at their ease: he would sit perched on the edge of a chair, listening intently to what they had to say and intervening occasionally to reassure them. He took no notes, but rarely forgot names or significant details. David Painter (1965) records that long before student counsellors became fashionable, his diary was full of appointments with undergraduates and others who wanted to consult him about faith, vocation, moral dilemmas and philosophical struggles, and there was always a warm welcome in his rooms on Staircase 4, even if the rooms themselves were sometimes a bit chilly, this being the result of his insistence on keeping the windows wide open, whatever the weather. “Must have fresh air” was his frequent mantra, and the fresh air was as much figurative as physical, in that he was impatient with those whose faith or religious practice was distorted with staleness or clutter. Andrew Bowden (1959) writes that Alec was the wisest adviser he has ever had, that he encouraged him to meet people and do things which moulded his career, and that on one occasion he saved him from making a disastrous career move. When asked for advice he pondered, spoke quietly, briefly and clearly, giving cogent reasons for his opinion. He always had time to listen, and he was not threatening.

As a tutor he earned great respect. Although he had not done a full undergraduate programme in theology, his voracious reading enabled him to cover a wide range of topics in theology and church history in his tutorials. David Painter writes that it is difficult to put into words the unquantifiable value of an ‘Alec tutorial’: “The topic for the week’s essay would be accompanied by a list of about a dozen books, as well as extracts from book reviews or articles in theological journals, and then, when the time came for the reading aloud of the essay, he would pick up his copy of that day’s Times and make notes in the margins as they read. With or without the notes, his acute mind enabled him to make detailed comments on the essay straight away, and he never let us get away with a point of view which was only hazily argued, or which depended on shaky grounds. Pious rhetoric especially annoyed him. ‘That was very beautiful, but what did it mean?’ If anyone wrote something which he thought should be challenged he would often go to his bookshelves and pull out a volume, banging the pages together in order to release the dust that had collected since it was last consulted. His encyclopaedic memory would generally enable him quickly to find a passage which would refute the arguments in the essay, after which he would ask ‘What do you make of that? Come on, how would you answer that?’ He especially warned his students against going to too many lectures, except, perhaps, those given by really outstanding teachers and exponents, of whom there were a great many in Oxford at the time. Basic lectures, which simply covered the syllabus for Schools, he described as ‘spoon-feeding’, and he urged students to ‘read the texts for yourselves, and don’t be content with other people’s answers. Be critical of what you read, and come to an understanding which you have worked out.’”

Some of his students came from outside the College, including Nicholas Coulton who recorded in his obituary of Alec in the Church Times that his one-hour tutorials were always followed by tea, fruit cake, and a walk outside to watch the College rugby team. The only sport in which he took part himself was fives, which he played aggressively, but he followed the sporting activities of the students generally.

Chapel services during his chaplaincy are well described by David Painter:

“They were conducted with reverence and care, though Alec had little time for elaborate ceremonial, believing that the words of the Prayer Book liturgy, which he clearly loved, should speak for themselves; hence the gentle and undemonstrative way in which he recited them. Evensong on Sundays was well attended, not least by the Provost and senior members, and those present in chapel could be confident, when he was preaching, of hearing a well-crafted and thought-provoking sermon, often quoting not only scripture but also classical literature, as well as the occasional Victorian novel. Although the theological fervour and sometimes challenging ideas of the 1960s were not often referred to, he had some sharp comments about those whom he thought excessively credulous about the contents of the Bible, or about certain aspects of church life and practice, and he more than once quoted with approval Samuel Coleridge’s famous dictum that ‘to doubt has more of faith – nay, even to disbelieve, than that blank negation of all thought and feeling which is the lot of the herd of church and meeting trotters’.”

He encouraged enquiry into debate on religious topics without any doctrinal presuppositions. A respected forum for discussion was the “Woodroffe Society”, named after the pioneer for the re-foundation of Gloucester Hall as Worcester College, which heard talks from eminent guests.

He was temperamentally opposed to militant expressions of faith although, along with a number of other college chaplains, he strongly supported the mission to the University headed by Trevor Huddleston organized by the SCM in Hilary term 1963’ and he gave to the Church Missionary Society.

By contrast, his political views were controversial and were often put forward in exaggerated form to provoke students into argument. As David Painter remarks, “He was unashamedly right-wing and was vehemently critical of the Labour Government of the 1960s, reserving particular scorn for the Prime Minister, Harold Wilson. Mary Wilson had incautiously said in an interview to the Sunday Times that if Harold had a fault it was drowning everything with HP sauce, and when Alec observed a bottle of the sauce on someone’s breakfast table in hall, he expostulated ‘Can’t think how you can swallow that stuff. That’s Wilson’s sauce – dreadful stuff!’.”

Nevertheless, his understanding and practice of the Christian faith involved social action, and he was an enthusiastic member of a small group of chaplains and other college representatives who organized annual summer camps at Spennithorne in the Yorkshire Dales together with an equal number of “Borstal” boys from institutions for young offenders. The idea was the brain-child of Joe Jory, rector of Spennithorne in Wensleydale, who was convinced that social integration would be furthered by mixing Oxford students with Borstal boys in the Yorkshire countryside. The project was enthusiastically supported at the Yorkshire end by Frank and Jane Theakston (of the Theakston brewery at Masham) and by the paraplegic athlete and campaigner Sue Masham (Baroness Masham of Ilton from 1970) whose father-in-law, the Earl of Swinton, was a landholder in the area. At the Oxford end there was a committee with representatives from half a dozen participating colleges, mostly represented by their chaplains and by Fr. Michael Hollings, the charismatic Roman Catholic chaplain to the University. For several years a dozen or so Worcester students camped for a week with an equal number of Borstal boys at Spennithorne before returning to stay with them in the Borstal. Each college was linked with a specific Borstal, and the boys who camped with the Worcester students came from the converted Victorian mansion at Hewell Grange near Redditch. Alec was particularly pleased with this pairing because Hewell Grange was situated not far from Sir Thomas Cookes’ stomping ground at Bromsgrove. The governor, Alan Roberton, was an astute and austere Scot who made it quite clear that he was sceptical of the value of the involvement of would-be do-gooders, but that he was willing for the boys in his charge to take part in the camps as a social exercise which would be likely to benefit the students as much as the Borstal boys. For many of the students who took part the experience was revelatory. Much goodwill was generated, and some practical skills were learned either officially in the Borstal (how to lay concrete or cut screws on metal pipe) or unofficially outside it (how to start a car without using a key).

As a Fellow of the College he had other duties. He was Dean of Degrees from 1962 and Tutor for Admissions from 1964 to 1967. Between 1966 and 1969 he organized reading parties for fellows and students of the College at Rydal Hall near Ambleside in the Lake District. David Painter remembers that a couple of dozen undergraduates would gather for serious reading, more or less in silence, during the morning, followed by a walk in the afternoon and then conversation or more reading after dinner. Despite the fact that it was early January the afternoon walk was no mere stroll along easy footpaths, but rather some vigorous fell-walking, with Alec often leading the way. The really keen types tackled Helvellyn, whereas others were content with more modest exercise; nevertheless, some degree of effort was expected on the part of everyone.

Early in his chaplaincy Alec undertook to translate Willy Rordoff’s heavy-duty book Sunday for the SCM Press. He completed it (published in 1968) but found it an irksome task. In spite of his undergraduate studies he never slipped easily into foreign languages on the continent. Nevertheless his training in language was reflected by his precise use of English, and his habit of teasing students who mis-used it. In this he had an ally in the Classical Mods tutor, Armitage Noel Bryan-Brown, a reserved and rather remote figure who made play of using words in their strictest etymological sense. Alec used to relate various anecdotes about him. One involved a candidate who claimed that he had covered all aspects of his subject. “Then”, said BB, “You have entirely obscured it from view”.

Alec lived during term time in his rooms in college, but he bought a cottage at Bladon near Woodstock which he used at weekends, and where he employed Mrs. Joyce, who had looked after his mother, as his housekeeper. At Bladon he frequently entertained small groups of students, especially on Sundays when they were put through a routine of a vigorous walk following early communion in the college chapel and before evensong, often fitting in a visit to his cottage at Bladon for an abundant meal of roast lamb. In the vacations he went on walking holidays with a few students from the college, first along Hadrian’s Wall (in the winter of 1962/3), and subsequently to many of the more remote mountain ranges in Scotland, including Torridon, the Isle of Rhum and the island of Lewis and Harris.

He was a generous host. His wine was always French and excellent, and his sherry very good. He supported numerous charities involved in philanthropic work, in heritage preservation, and the protection of the countryside. He made a practice of always giving to beggars, believing that it was his Christian duty to give to everyone that asks. But in his personal life he balanced generosity with extreme thrift. “Look after the pennies and the pounds will look after themselves”, and “Waste not want not” (usually abbreviated to “WNWN”) were mantras for living that he repeated frequently. He used economy labels for as long as the Post Office continued to provide them: pre-stamped and pre-glued labels that could be licked and stuck over used envelopes so that they could be used again. Alastair Small ridiculed the practice by giving him a Christmas card with the words “Not to be used again until Christmas 1962” written in pencil. It came back the next year with the date adjusted, and acquired a companion card. The two went backwards and forwards for 50 years, giving the lie to assumptions made about the reliability of the Italian and Canadian postal systems. A similar contradiction applied to dress. He would dress immaculately for formal occasions, but when at home in Bladon or walking in the countryside he would wear the same woollen jersey that he had acquired during national service, the same tweed jacket with patched elbows, and the same long fawn raincoat with belt and buckle. The same rucksack lasted him throughout his life.

During his chaplaincy at Worcester Alec got to know Robert Runcie, the future Archbishop of Canterbury, who was Principal of Cuddesdon Theological College from 1960-1970. Alec gave occasional lectures at Cuddesdon for Runcie and Runcie preached at Evensong in Worcester chapel on several memorable occasions. His support was important for the development of Alec’s career.

He left Worcester in 1970 to become Warden of Lincoln Theological College and was made a canon of Lincoln Cathedral. At this time theological colleges were having to adapt to a changed role as the number of men seeking ordination declined sharply while the number of women wanting to become deaconesses in the hope that this might eventually open their way to the full priesthood increased. Under Alec’s wardenship they were all made welcome and provided with a rigorous and stimulating theological education. One of his students, Peter Bradley, later archdeacon of Warrington, records that he lectured well and enjoyed engaging in robust theological debate, usually concluding that despite the latest heretical theory, ‘there is nothing new!’. One of his first students was Richard Chartres, later Bishop of London whom Alec accepted in the college at a critical stage of his career: he was ordained in St Albans Abbey in 1973.

While he was at Lincoln Alec acquired the first of the series of three dogs that were to be his devoted companions for most of the rest of his life: a black Labrador which he called Leah after the tender-eyed daughter of Laban in the book of Genesis. She accompanied him on his vigorous walks with students from the college.

In 1977, Runcie, now Bishop of St Albans, nominated Alec as Suffragan Bishop of Bedford. He was consecrated a bishop by Donald Coggan, Archbishop of Canterbury, at Westminster Abbey on 31 March 1977. Bedford was an unfamiliar environment, supposedly in 1977 the most ethnically, culturally, and racially mixed town in the country; it had a declining industrial economy, and it was the home town of John Bunyan whose brand of 17th century puritanism was alien to the high Anglican tradition in which Alec had been brought up. As in all his posts, he immersed himself in the historical traditions of the place, and engaged with the current concerns of the population. He enjoyed his post there.

In 1981, a year after Runcie’s translation to Canterbury as Archbishop, Alec was appointed Bishop of Newcastle, at that time in the grip of economic depression. Church attendance was declining, and morale was low among the clergy. Alec set out to improve relations between the civic authorities and the diocese, and to develop links with other Churches. He appointed an Officer for Inter-denominational relations, Clive Price, who recalls that the position initially seemed rather daunting but that he soon discovered that, as long as he marshalled his arguments properly and was ready to answer Alec’s questions about an ecumenical venture he was proposing, then Alec would support him even if it would not have been his natural inclination. Sometimes a vicar would write to him seeking his permission for some ecumenical activity in which he or she wished to engage. Alec would reply, telling the vicar to seek Clive’s advice and follow his directions. This confidence in him was enormously gratifying.

Alec also made friends in other Faith Communities. When he retired a group of them gave him a framed Commendation praising his commitment to inter-faith relations and ending “Friends from all the Faith Communities are truly indebted to you for the leadership you have provided in bringing about unity amongst people of different Faith Communities in Newcastle upon Tyne”.

Newcastle was famous for its history in the development of steam engines and Alec had been passionately interested in railways, since early childhood. He used his maiden speech as a diocesan bishop in the House of Lords to urge the preservation of the Settle to Carlisle railway line, now known as one the most scenic lines in the United Kingdom, which at that time was in danger of being closed; but he was not just a preservationist. It gave him great pleasure as bishop to name one of the first of the Class 91 (InterCity 225) locomotives “Saint Nicholas” on December 5th 1992, after the completion of the electrification of the East Coast Line, and one of the last of the Class 47 diesel-electric locomotives “Saint Augustine” on June 24th, 1996. The choice of names can have given him little difficulty since Saint Nicholas was the patron saint of Newcastle Cathedral, and Saint Augustine was in Alec’s opinion the most important of the Early Christian Doctors of the Church. On both occasions he was presented with a model of the locomotive.

His preaching style became well known in the diocese. He was always clear and succinct, and never rhetorical, although he liked to repeat a key phrase from the Bible to make a significant point. He was noted for dropping each sheet of notes as he finished with it so as not to risk repeating himself. Everybody would watch the leaf of paper floating down to the floor. His dislike of vacuous sentiment also became known. Clive Price remembers a time when he acted as Alec’s Chaplain at an Induction to a rural parish in the Tyne valley. As the service proceeded they were together at the east end of the church while the congregation sang a hymn. Alec said to him “I don’t like this hymn”. “Oh”, said Clive, “why not?” “They don’t mean it”, said Alec, as the congregation sang “Take my silver and my gold, not a mite would I withhold”.

As bishop he was responsible for the welfare of his clergy, and he lost no time in getting to know them. Zillah (named after another obscure figure in the book of Genesis), a golden Labrador who had replaced Leah, was a useful adjunct. She attended all meetings held in his house and created an air of informality appreciated by many (though not all) of his guests. In a valedictory article published on his retirement from the diocese in the diocesan newspaper New Link, one of his Rural Deans recorded that when he went in to be interviewed for his post, Bishop Alec waved him to a seat on a couch across from himself, the Archdeacon and the Deanery Chairperson. Zillah was sitting on nine-tenths of a chair, with the bishop perched on the remaining tenth. As he sat down, the dog left the bishop, meandered across and climbed onto the couch, laying her head on his knee. Alec telephoned later to offer him the job.

Such eccentricities served a useful purpose in deflating pomposity, and they obscured the fact that in administrative matters and in carrying out his ecclesiastical duties Alec was always diligent and well prepared. His methods were traditional. He was averse to new technology: he had no computer and made little use of fax machines, relying instead on his address book, his appointments diary, his telephone and his extremely retentive memory. Important messages might be dictated to a secretary and typed by her, but were more likely to be hand-written in his distinctive scrawl. His system worked well for him. In 1983 he was appointed chairman of the Advisory Council for the Church’s Ministry (ACCM), intended to “promote the most effective form of accredited ministry, ordained and lay, in the mission of the Church, and to make appropriate recommendations for this purpose to the Bishops and to the General Synod”. The choice of Alec for the post is surprising since he was initially opposed to the ordination of women, already a burning issued in the church, but he made no attempt to influence the committee one way or the other on the subject; and he came to accept that the ordination of women, and in due course their consecration as bishops, was “not only necessary but desirable”.

He gave up the chair of ACCM in 1987 to take on the role of Chair of the church’s Doctrine Commission charged with reporting on important theological questions. It produced reports on We Believe in the Holy Spirit (1989) and The Mystery of Salvation (1995) under his chairmanship. The Commission also had to liaise with the Liturgical Commission over the theological aspects of the revision of the Church of England’s worship. In his obituary of Alec, Nicholas Coulton (Provost / Dean of Newcastle from 1990 to 2003) commented that while the Church experienced sharp divisions, Alec held together members with diverse theologies. When he gave up the Chair of the Commission in 1995, he was made DD Lambeth in recognition of his work.

But the openness of mind which made Alec a good Chair of the Doctrine Commission was not universally appreciated in the diocese. The conservative evangelical tradition, based on the belief in the inerrancy of the bible, had long been strong in Newcastle and Alec had an uneasy relationship with David Holloway, vicar of the Clayton Memorial Church in Jesmond and one of the most prominent spokesmen of this viewpoint, who has been the scourge of successive bishops of Newcastle.

Richard Hooper (1959) remembers a chance meeting at Kings Cross station when Alec was Bishop of Newcastle. Alec was resplendent in purple. Richard and his Australian wife Meredith (Alec had married them in Worcester College Chapel in March 1964) were travelling to York. So was Alec. During the whole journey Alec excitedly pointed out every ecclesiastical landmark through the train windows – and there were a lot! Back in his office, Richard wrote a letter of thanks to Alec and asked his PA to address and post it to the Bishop of Newcastle. Richard was surprised to hear nothing back from Alec for quite a while. Then came the explanation from Alec in typical jovial manner. The letter had gone to the wrong Bishop of Newcastle. Richard’s PA at the time was a Catholic.

Alec retired from the bishopric in 1997, and was awarded an Hon. DCL at Northumbria University. He went to live at Fell End, a converted small farmhouse in the hamlet of Butterwick situated between Bampton and Askham in the valley of the River Lowther, about five miles north-west of Shap. It was, he said, ‘connoisseur’s country’ on the fringes of the Lake District and sharing in its traditions, but with less dramatic landscapes and fewer tourists than better-known places in the core of the region. Some of his friends feared that without the stimulus of ecclesiastical duties he might turn into a recluse, but this was a misconception. Once installed in his new home he sent invitations to all his neighbours inviting them to a party. Many came, and he was quickly accepted into the local community. They found him a rather remote figure who had little use for small talk, but they also found that he had a real interest in their concerns and enjoyed banter.

Until then he had always employed a housekeeper, with several successors to Mrs. Joyce; but his attempts to find a suitable person failed. It was easy enough to find a cleaner, but not a cook. He had had no experience of cooking, so he registered for cooking classes at Kendal College, and learned to produce delicious uncomplicated meals. He involved himself in local conservation issues and in the preservation of rights of way. In other respects his life-style changed little. He continued to offer hospitality to numerous friends, and he retained his old habits of wearing shabby clothes, but not his tweed jacket which his neighbour Wendy Martin, red-squirrel conservationist and organic gardener, finally persuaded him to surrender to be recycled on her compost-heap.

The Lake district provided endless opportunities for walking although the length and difficulty of the walks decreased with the passage of time. His canine companion was now Belle, an affectionate collie whom he acquired from the father of Andrew Wingate (Worcester 1962) who had been his student at Worcester and at Lincoln Theological College when she was already mature. It is likely that she had previously been involved in a car crash because when she was put in the back of a car she would bark at any vehicle that passed and scrabble frantically at the upholstery. Alec took her on a dog therapy training course but it had little effect. She aged along with her master and died shortly before he became incapacitated.

Alec always enjoyed foreign travel. The obituary in the Church Times is entirely wrong in this respect. Even before his retirement he travelled extensively. In 1979 he visited Andrew and Angela Wingate in Madurai, South India where Andrew was teaching in the Tamil Nadu Theological Seminary. Andrew recalls that Alec was keen to experience all that he could in the weeks that he stayed with them in the seminary. He came every day to the early chapel at 6.30 a.m., and went with Andrew to the ashram of the Benedictine monk Fr. Bede Griffiths where they stayed for two or three days. They travelled on the footplate of a regular local steam train from Madurai Junction southwards to Tirunelveli, aided by the railwaymen who came from the church in a railway colony near the seminary. They travelled to Bangalore where they stayed with Bonnama the widow of a student who had been on a short course at Lincoln Theological College; and they made a memorable visit to the hill station of Kodaikanal where they stayed with the elderly chaplain there, Arthur Bagshaw. Alec entered fully into the hill station life for three or four days, including playing bridge with fellow members of the congregation. (That experience may have been of doubtful value since Alec was not a good bridge player). For the return journey they decided to walk down from the hill station to the plain, and employed a local loin-cloth clad guide to help them find the way. He had to cut a path for them down through the trees, and Andrew reflected on how many rupees Alec carried in his wallet and how trusting he was.

(Photo: Left to right -Chris Oliver (Worcester, 1959), The Revd Michael Champneys, A.A.K.G in the Garwahl, 2002).

In February 1992 Alec visited Alastair and Carola Small in the Canadian Rockies, where he soon gave up attempts to get around on cross-country skis, but crossed Bow Lake happily on snow shoes. For many years he went on train journeys in Europe with George Young. Retirement opened up more opportunities for travel. He visited Darjeeling and Simla, and went trekking in the Garwahl in the Indian part of the Himalayas in 2002. For a number of years he signed up for cultural tours with Special Tours guided by Susie Orso who became a good friend. He remembered especially visits to Ethiopia and Uzbekistan, and above all, a visit to the monastery of St Catherine on Mount Sinai. More recently, when he could no longer go on group tours, he went on short holidays with Alastair and Carola to Greece, Italy and Spain, focussed usually on places (Santiago, Naples) with good baroque architecture of which he was fond. He never took photographs but he would buy numerous postcards to send to friends. They responded in kind, and the shelves and bookcases at Fell End were littered with accumulated postcards.

He maintained some ecclesiastical roles in retirement. He continued to serve as an honorary assistant bishop in the Diocese of Carlisle, and frequently conducted services in the churches of the united benefice of Shap with Swindale and Bampton with Mardale on behalf of its incumbents until about 2015 when his increasing weakness made this impossible. The grace with which he accepted their ministrations – one had trained for the priesthood under him at Lincoln and had good reason to feel inadequate in the presence of such a distinguished theologian and pastor; and two others, both women, would have been well aware of his earlier hesitancy over women’s ordination – revealed a humility which was often (probably deliberately!) concealed by his abrupt, no-nonsense manner. They all enjoyed his unfailing support, and Alec, who had always said how much he enjoyed visiting the small rural congregations in his care, was now a member of one – St Patrick’s, Bampton – for the first time in his life.

Much of his spare time was spent reviewing books for the Church Times which sent him books on a wide range of subjects in theology and church history. In this way he continued to build up his large personal library. He continued to review books even after his physical frailty had made him house-bound. His constituency MP, Rory Stuart, who lived nearby, listed some of his cherished neighbours in his farewell letter to his constituents published in the Cumberland and Westmorland Herald of 9 November 2019. They included ‘the Bishop still bent over his austere and lonely scholarship’.

For his 70th birthday he invited various friends to accompany him on a trip to St Kilda, for which he hired a small tour boat from Loch Roag. So many of them accepted the invitation that he had to go twice with two different groups of guests. They slept on the boat for three nights in the bay at St Kilda, and had plenty of time to explore the island. On the second trip he arranged a special service in the restored village church. For the Old Testament reading he chose the passage in the last chapter of Ecclesiastes about physical frailty and the transitory nature of human life.

By then he was already beginning to suffer from loss of muscular control in his fingers which became gradually more problematic over the next twenty years. He began to experience heart problems in his early 70s, and had a triple by-pass operation shortly before his 80th birthday, which he delayed celebrating until 2010 when he organized a chartered boat trip for many friends on Ullswater.

In May 2014 Alec took the train to London for the memorial service of George Young, intending to stay as usual in the Oxford and Cambridge Club; but he fell in Trafalgar Square, and was picked up unconscious and taken to hospital. He was then transferred by ambulance to Carlisle hospital before being brought back to Fell End. He was no longer able to live by himself, so after a short time when he was looked after by friends, arrangements were made for live-in care. He gradually declined both physically and mentally, but bore this patiently and retained his courteous attitude to those looking after him. If asked how he was doing, he would reply “moderately well”. This arrangement lasted until late summer 2020 when he fell and broke his pelvis. After another spell in Carlisle Hospital he was brought back to Fell End. He was now bedridden and unable to take solid medicine, so new arrangements were made for more intensive care. He slipped away attended by two carers and by Paul Harris, the son of his late cousin Peter, on 9 May 2021.

Alec always looked back on his time at Worcester as a particularly happy period in his life. The college too valued the contribution that he made to it. Lord Franks, always reserved, is said to have remarked when Alec left to become warden of Lincoln Theological College that Mr Graham had been a very good Chaplain indeed. Dick Smethurst records that when he became Bishop of Newcastle in 1981 the fellows elected him to an Honorary Fellowship, whereas former Fellows are usually elected to Emeritus Fellowships. This was the result of pressure from Harry Pitt, who held Alec’s pastoral work throughout the College in the highest esteem from his standpoint of Dean. Alec also maintained close relations with his own undergraduate college, St John’s, where he was elected to an Honorary Fellowship in 1986. In his will he made generous bequests to both colleges, but especially to Worcester where he intended his legacy to be used primarily to endow a Tutorial Fellowship and if necessary the associated University Lectureship in Theology, “the holder to be a specialist in the study of one or more of the Old Testament, the New Testament, Christian Doctrine and Christian Church History”, and secondly to support the costs of the College chapel.

In a note to his executors Alec prescribed that his funeral should be private, and should be held in the chapel at St John’s Cemetery, Margate before interment in his family’s grave. He was buried there on 26 May 2021 with the full and unaltered liturgy of the burial service in the Book of Common Prayer. In the same note he prescribed that there should be no memorial service anywhere, and no address, sermon, memoir or eulogy whatsoever, though refreshments could be provided after the burial. These strictures are fully consonant with his sense of the vanity of human life as expressed in the book of Ecclesiastes, but they have been a source of regret to his many friends who would have wanted to get together to celebrate the memory of an extraordinary man who has had a profound influence on their lives. This memoir may violate his wishes, but it is written in the belief that no-one should be permitted to write themselves out of history.

Professor Alastair Small (1960)